It is scandalous it took us so long to dedicate a proper memorial to the American

servicemen who served in WWI, but at least when we finally did, we did it right.

Arguably, WWI perhaps looms larger in the Australian public consciousness,

thanks to Gallipoli (the battle and the film). They were in France too.

Farm-raised Jim Collins is one of the Australians fighting a war of inches

behind French lines in Jordan Prince-Wright’s Before Dawn, which

releases tomorrow on DVD/BluRay.

Collins

and his mates want to enlist, because they believe it will be an adventure that

will lead to later dividends. He assumes his father opposes because he wants to

keep him on the farm. However, when he reaches France, Collins realizes this

war is nothing like he imagined—and it will not end anytime soon.

In

a baptism of fire, their corporal takes Collins and three mates on a mission

into no man’s land on their first night in the trenches. Only Collins returns.

He blames himself for at least one of their deaths, because he could not kill a

German soldier who looked even younger than himself. Consequently, he takes

greater risks to save other Allied soldiers, as the weeks drag into months and

even years.

There

is a lot that works in Before Dawn, but just as the generals were

fighting prior wars with new technology, Prince-Wright is largely hemmed in by

the cinematic vocabulary of the various film versions of All Quiet on the Western Front. Few films have successfully broken out of the trench

straight-jacket, but it has been done by the likes of 1917, The Blue

Max, and, ironically, the animated Sgt. Stubby (which is probably

the best of the lot).

Nevertheless,

the gritty realism of Before Dawn packs a punch and the warfighting

special effects are impressive, in an immersive kind of way. Prince-Wright

conveys a visceral sense of how the mud and muck were a constant, demoralizing presence,

as well as the sudden randomness of death.

Levi

Miller credibly portrays Collins’ harsh maturation, but never in a way that

truly surprises the audience. Instead, Myles Pollard somewhat overshadows him

as the battle-hardened and also secretly battle-scarred Sgt. Beaufort, who

maybe should have been the focal character, as perceived by Collins.

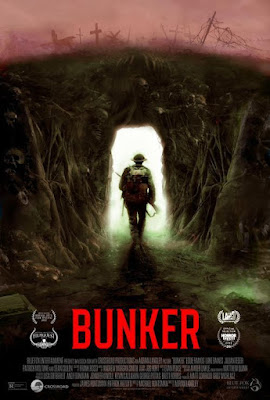

Private Segura is probably a lot like my great-grandfather, who served in WWI as

a member of the New Mexico National Guard, even though it had only been a state

since 1912. However, Segura encounters something supernaturally evil in a

German bunker that Great-grandfather never had to worry about—presumably, since

you are reading this review. The Germans suddenly don’t look so bad in Adrian

Langley’s Bunker, which opens Friday in theaters.

Lucky

Segura is a medic, who is part of the paltry reinforcements Captain Hall

delivers to Lt. Turner. His primarily British contingent has been locked in a stalemate

that appears set in concrete. Yet, rather inexplicably, it appears the Germans

have completely abandoned their positions, so Turner mobilizes his battered

remnants to capture that ground. What they find in the bunker is a German,

strung up crucifixion-style.

Turner

has Segura tend to the POW, in hopes of eliciting answers. However, they are interrupted

when the Germans start shelling their own abandoned bunker, cutting off the

rag-tag Allies from the above-ground. Then people start acting a little twitchy—and

then more than a little crazy.

For

obvious reasons, Bunker is very similar in tone to Trench 11, but

the horror element is supernatural rather than monstrous. In some ways, it

almost feels like a dark parable, but there is an evil entity that eventually

reveals himself—and the creature design work bringing it to life is pretty

cool.

Eddie

Ramos is also rock-solid anchoring the film as Segura. His tough street smarts

contrast well with the Brits, especially Patrick Moltane as the martinet

Turner. Think of him as Benedict Cumberbatch’s 1917 officer magically

inserted into a horror film. Indeed, Moltane goes nuts pretty spectacularly.

Luke Baines is also enormously creepy as the mysterious POW.

The hardware and uniforms change, but the fog of war remains. This film also

suggests the young people asks to fight wars are in many ways quite similar—identical

in fact. The same cast plays out life-and-death encounters from the Civil War,

WWI and Iraq Wars during Jack Fessenden’s Foxhole, which opens tomorrow

in New York.

Jackson

is a Buffalo Soldier who basically crashed a small Union company’s foxhole, after

a Confederate officer wounded him, perhaps mortally. Conrad and old grizzled

Wilson believe some of the men should carry him to the distant field hospital,

but Clark (presumably hailing from border state hill country) argues Jackson

would probably die on the journey and the medics maybe wouldn’t take him

anyway.

There

is a similar ethical dilemma for the company when then film advances to WWI. They

have captured a German soldier in their trench at an inconvenient time, so

their sergeant wants to kill him and be done with it. Again, Wilson objects and

so does Jackson, a soldier from a black regiment, who is somewhat more readily

accepted by the white doughboys.

Easily,

the best of the three stories is the conclusion in Iraq—but at least a country

mile. By now, Jackson is the leader of the squad. There is no internal

dissension within the group and they will face no ethical dilemmas. Instead,

they will merely try to survive, without leaving any men behind (including Gale,

a new addition to the platoon), when they are separated from their convoy and

ambushed by insurgents with an RPG launcher.

Of

the three installments, the dialogue of the Iraq section sounds the most like

the military talk I’ve heard (from family). It also forgoes the anti-war moralizing,

instead portraying the courage and camaraderie of the U.S. military. It actually

makes Foxhole more effective as anti-war critique, because it shows two sides

to the combat experience (and the dangers and difficulties they entail), while

inviting sympathy for the men and women in uniform.

It

is also the tensest and most skillfully executed. In this case, the definition

of foxhole is expanded to include the Humvee the soldiers are dug into.

Fessenden (son of Larry, on-board as a producer) uses the blinding sand to

narrow the audience’s field of vision, creating an uneasy feeling that a fatal

shot could come from anywhere, at any time.

Only war can make a twenty-year-old this emotionally deadened and world-weary.

That is what happens to Arturs Vanags. During a four year-period, he

technically switches sides several times, first fighting against the Germans

for the Russians, then against the Soviets, and finally against both. Yet, he

always fights for Latvia. Viewers will see WWI turn into the Latvian War for

Independence through the eyes of a young recruit in Dzintars Dreibergs’ Blizzard

of Souls, Latvia’s official International Oscar submission and its all-time

domestically-produced box office champ, which opens virtually this Friday.

After

Germans casually kill his mother, Vanags and his father reluctantly flee their

farm to Riga, where they enlist in the Latvian army. Technically, Vanags is too

young, but his father gives his permission. Technically, the stern veteran is

too old, but his sterling war record makes him valuable as a sergeant major (or

the rough equivalent). Much to Vanags’s surprise, his father is probably harder

on him than the other recruits, but veterans will well understand why.

During

the first act, Blizzard follows the traditional arc of WWI movies, with

the green enlisted men dealing with the horrible routine of trench warfare. However,

the war will take a series of unusual turns for Vanags and his colleagues, because

of the fateful position of the Baltics. Although they initially march to war

wearing Latvian uniforms, they are clearly considered subservient to the

Russian army (they aren’t even allowed to sing their national anthem). After

the Revolution, the Bolsheviks first talk peace, but then start waging war

again. Most of the Latvian Riflemen Corps are absorbed into the Latvian SSR,

which again functions as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Soviets. Inevitably,

the call for genuine independence and the Soviets’ brutal purges drove

experienced soldiers like Vanags into the Independence Brigades.

Screenwriter

Boris Frumin makes all this complex military history quite clear, while maintaining

the focus on Vanags’ grunt-level survival story. Oto Brantevics could not

possibly look more milquetoast is his early scenes as young Vanags, but he

undergoes a harrowing transformation, even more dramatic than George MacKay’s

in 1917. MacKay provides far and away the most memorable performance in

Mendes’ Oscar nominee, but Martins Vilsons is just as strong, or even stronger

as crusty Old Man Vanags. It is a quiet but colorful and ultimately deeply

humanistic portrayal.