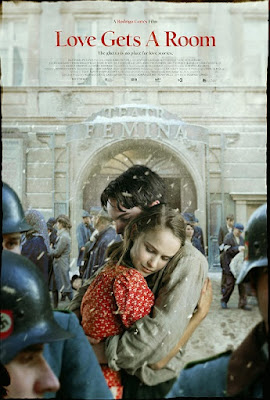

Their audience could use a good laugh, but they are forbidden to clap. In 1942, the Femina Theatre in the Warsaw Ghetto did indeed open a door-slamming musical farce written by Jerzy Jurandot. On the surface, it would seem to have little relevance to lives of its audience and cast. However, as the characters on-stage shift partners, the participants in a backstage love triangle wrestle with some life-and-death questions, as well as whom they plan to face them with in Rodrigo Cortes’s Love Gets a Room, which releases today in theaters and on-demand.

Stefcia is a survivor, as we see from the way she navigates the ghetto in the opening sequence, helping others to survive grim encounters with their German captors, on her way to the theaters. The play is Jerzy Jurandot’s Love Gets a Room, which would explain the film’s seemingly inapt title. Rather awkwardly, Stefcia stars as the newlywed wife of her torch-carrying ex-lover Patrik, while co-starring with her current lover Edmund, who plays the husband of her friend Ada.

In the play-within-the-play, both couples are assigned the same apartment by the Ghetto’s Jewish Council, so they decide to make the best of it and live together. Of course, during the course of the stage play, the four newlyweds inevitably start to fall in love with their opposite’s mates. Behind the scenes, Patrik reveals he has bribed a National Socialist officer to allow him to escape. He wants Stefcia to come with him, even though he knows she no longer loves him. Somewhat to her annoyance, Edmund wants her to agree, because it is clear by this point what will happen to those who remain in the Ghetto.

Apparently, most of the film unfolds in real-time during the performance of Jurandot’s play, which was reconstructed for Cortes’s film. The text and lyrics all survived, but new era-appropriate music was composed by Victor Reyes. However, their performance is not entirely faithful. As the intrigue grows backstage, cues are missed, requiring some rather raggedy improvisation.

Yet, that is all part of the intelligence of Cortes’ screenplay and his success realizing it on-screen. Cortes has been off-the-radar since the disappointment of Red Lights, but Love Gets a Room represents a significant creative comeback. The parallels between on-stage and backstage are cleverly executed and the long tracking shots give the film a sense of dramatic tension akin to live stage performance.