Admittedly, these two teens are about to die, but don’t think of it as a downer.

This way, the lucky cousins will learn their purposes in life—short though they

were. Yet, unlike Robin Williams in What Dreams May Come, they might be

able to return to their interrupted earthly lives, so they apply their epiphanies

with their memories intact—maybe, just maybe. Unfortunately, their journey of self-discovery

entails more than just one trip to Hell. They must visit several in Isamu Imakake’s

Happy Science-produced Dragon Heart, which opens this Friday in Los

Angeles.

Blame

the kappa, who lured Tomomi Sato and her visiting cousin, Ryusuke Tagawa into

treacherous currents. Apparently, that was that, but Ameno Hiwashino Mikoto,

the god of the local Shinto shrine invites them to explore the spirit realm.

Much to their surprise, the tour quickly takes on Divine Comedy parallels.

First,

they materialize in a violent gangster world, where the damned constantly murder

each other. From there, they fall into a bizarre Lynchian hospital, which

dispenses a distinctly sinister variety of care, very much in the surreal

tradition of Inoperable or Fractured. It is a nightmarish place, yet

it is also where they witness the redemption and rescue of a tormented soul. That

plants a seed with Sato and Tagawa, giving them a notion this might be

something they want to do.

However,

it will take some doing before they can start saving souls. To get to that point,

they must escape from a snake queen and find the hidden enclave of Shambhala to

start their advanced spiritual training.

Dragon

Heart is the

latest anime feature based on the teachings of the Happy Science movement. In

terms of the level of proselytization, this film falls somewhere between The Mystical Laws and The Laws of the Universe: The Age of Elohim. There

are times when the spiritual content feels very heavy-handed. Yet, the uninitiated

would be hard-pressed to explain the film’s foundational doctrines, beyond

generalities like believe on God and recognize the soul is man’s true form rather

than the body. Indeed, for pagans, the film seems to freely mix Shinto, Buddhist,

Hindu, and Christian symbolism, cafeteria-style.

Regardless,

the level of animation remains surprisingly high. Imakake worked on several

major anime properties prior to helming Happy Science’s animated features

(including Cowboy Bebop, Evangelion, and Lupin III), so the level

of animation is always professional grade. In fact, many of fantastical

landscapes are really quite visually striking.

It is a term rich with anime and folkloric significance. “Mononoke” are vengeful spirits,

not unlike yokai. Miyazaki’s “Princess Mononoke” was not really a mononoke, but

rather a human foundling who had a rapport with spirit creatures. The mononoke

of the Mononoke anime and manga franchise are definitely mononoke. In

fact, they are about as mononoke as they get. It is the “Medicine Seller’s”

calling to exorcise them. Think of him as a medicine man, in that he holds

shaman-like powers and peddles medicinal cures. He cuts an odd figure, but even

the most secretive and powerful players in the Edo court will not turn him away

when an enraged spirit terrorizes their Lord’s harem chambers in Kenji Nakamura

& Kiyotaka Suzuki’s Mononoke the Movie: Chapter II—The Ashes of Rage,

produced by Toei Animation, which premieres today on Netflix.

Thanks

to the Medicine Seller, the Lord Tenshi’s concubines already survived one

incredibly put-out mononoke in the previous film (which was a continuation from

the 2007 anime series). Unfortunately, just when you thought it was safe to go

back to harem’s super-restricted Ooku, another mononoke strikes. Obviously, the

Medicine Seller needs to investigate, but his all-access pass is no longer

valid, because it was issued by the former Ooku manager—now deceased.

Tensions

were rising in the Ooku, even before the new mononoke peril emerged. The unseen

Tenshi’s favorite, Fuki Tokita is showing signs of pregnancy, which should be a

good thing, because an heir is needed. However, Tokita hails from “common stock,”

even though we would probably consider her family middle to upper-middle class,

from out contemporary perspective. Regardless, the prospect of debasing the

Imperial lineage with common stock and allowing a less than pristinely noble

family that kind of influence has the elite power-brokers alarmed.

Botan

Otomo is perfectly placed to take action. She was selected to serve as the new Ooku

manager because of her family’s power and prestige. As Tokita’s longtime rival,

she openly resents Fuki’s inappropriately close relationship with Tenshi.

However, she also feels loyalty to her Imperial lord and his prospective heir,

whoever it might be. Instead, it is the angry mononoke of a wronged concubine

who terrorizes the Ooku halls. Yet, before the Medicine Seller can dispel it,

he must learn the reason for its grudge—much like Christian exorcists need a

demon’s name to take dominion over it.

Without

question, Nakamura’s Mononoke films represent an energizing respite from

overly slick (and consequently soulless) 3D computer generated animation. While

digital techniques were employed, the Mononoke features have an eye-popping,

mind-blowing baroque style that resemble a fusion of Edo-era ukiyo-e woodcuts

with Peter Max headshop posters. Each frame is an absolute explosion of color.

Frankly, it is a good thing Ashes of Rage is a relative shorty, because extended

exposure to the utterly distinctive animation could induce sensory overload.

Yet, it is always wildly cool to behold.

In this film, the two heroic protagonists of Masamune Shirow’s Appleseed franchise

sort of get the DC treatment. They are the same characters fans know and love,

but they now have a new narrative continuity—familiar, but slightly different.

It is also sort of a prequel, but Briareos is already a cyborg—and partly on

the fritz. Unfortunately, the world is also still mostly destroyed, especially

the post-apocalyptic New York City, or perhaps it is just post-Mamdani. Regardless,

hope is in short supply, until Briareos and his comrade-life partner Deunan decide

to go out and find some in Shinji Aramaki’s anime feature, Appleseed Alpha,

which starts streaming today on Tubi.

WWIII bombed

out Times Square, yet the jumbotron remains, broadcasting old, pointless propaganda.

Some people still call the City home, including the cyborg gangster, Two Horns (because

of his Viking-like headpiece). Unfortunately, Deunan owes Two Horns money, so she

and Briareos must complete dangerous assignments, like that of the opening prologue,

to pay off the debt.

Rather

ominously, the two former soldiers suspect Two Horns has been setting them up

for failure. Yet, they have little choice, because Two Horns’s maintenance guy is

pretty much the only game in the post-apocalyptic town. Without power, Briareos

cannot do much, so they accept the next crummy gig: neutralizing and scavenging

a pack of rogue soldier-bots outside of town.

This

would be easier work if Briareos were in better shape. Regardless, things get

interesting when a group of mech-mercs drive into the drone zone with their

abductees, Olson, an enhanced but not full cybernetic former soldier, and Iris,

the young girl he was protecting. It turns out they are from the rumored sanctuary

of Olympus, which will mean a lot more to longstanding franchise fans. They are

also on a mission that Briareos and Deunan will join and ultimately embrace. Meanwhile,

the shadowy cabal trying to capture Iris follows their trail back to Two Horns,

bringing him into the fray as an unstable wild card.

Essentially,

Alpha arranges things differently on the timeline, but it closely hews

to the heart and spirit of the previous anime films. Briareos and Deunan are a

compelling beauty-and-the-beast couple, who have terrific battlefield chemistry

together. That last part is important, because Aramaki unleashes wall-to-wall

action. This kind of light-mecha combat really plays to his animation

strengths.

The computer-generated

motion-capture (but not full rotoscope) animation looks better here than it did

in Aramaki’s later film, Starship Trooper: Traitor of Mars. Perhaps the

distinctive, practically robotic look of Briareos (who reportedly influenced

the design of Blomkamp’s Chappie—you can see it in the ears) and Two

Horns helped focus the efforts at humanization on Deunan, Olson, and Iris.

In the Hatsune

Miku: Colorful Stage “rhythm game,” virtual singers are sort of like the

literary characters who come alive in Twilight Zone episodes, except it

is a relatively common phenomenon. Supposedly, if real-life singers perform

with enough emotion, they can bring their virtual collaborators to life and

even join them in “Sekai,” special dedicated rooms in the dimension between the

IRL and virtual worlds. Weirdly, several bands and their virtual “Mikus”

encounter a mysterious new Miku who cannot connect musically in Hiroyuki Hata’s

anime feature, Colorful Stage! The Movie: A Miku Who Can’t Sing,

produced by animation house P.A. House and released by GKIDS, which starts a

limited 4-day theatrical release today.

Move

over Minecraft, because Hata and screenwriter Yoko Yonaiyama managed to

adapt a game not unlike Guitar Hero or old-fashioned karaoke. However,

there was a large cast of pre-existing characters whom Yonaiyama assumed the

audience would already know. There is a bit of catching up to do, but astute

viewers will hopefully pick things up as they go.

Several

bands have connected with the own virtual collaborators in their specific Sekai.

For Ichika Hoshino that would be Hatsume Miku, who is about the purest

incarnation of a j-pop idol as you could envision. One day, she also encounters

a new Miku, who looks somewhat similar, but is much less self-assured. She

seems to travel through digital screens, producing static and distortions. Ironically,

the frustration caused by her service disruptions makes new Miku’s challenge to

connect on an emotional level even more difficult.

Nevertheless,

the four bands she reaches out to do their best to help, but they cannot

coordinate their efforts, because the alternate Miku communicates with them on

different wavelengths, or something like that. They feel for her and the

creators she is supposed to be attuned with. Unfortunately, the real-life

people hardwired to her Sekai cannot reach it, because they are all mired in

states of creative and emotional crisis. In fact, their aggregated depression

could drag the new Miku down as well.

It

bears repeating, the rules of the Colorful Stage world are a tad

confusing for newcomers, but that is the general idea. Regardless, it is pretty

impressive how Hata and Yonaiyama built a full feature length narrative out of

a smart-phone game that previously spawned a dozen or so ultra-mini anime

webisodes.

While

there are some thematic similarities with Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle, Colorful

Stage! The Movie serves up some interesting world-building. In fact, it

would nicely fit with Belle, Summer Wars, The Matrix, Tron, and

World on a Wire in film series exploring the porous border between the physical

and digital worlds.

The

Tomoe Academy was not exactly A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, but it was quite progressive

for its era. That would be the Tojo Era. Tetsuko Kuroyanagi’s parents were relatively

modern and somewhat Westernized, putting them a little out of step. Little

Kuroyanagi (a.k.a. Totto-Chan) also happens to be a free-thinker, which causes

her trouble at most schools. However, Tomoe’s Principal Kobayashi can handle

her just fine in Shinnosuke Yakuwa’s Totto-Chan: The Little Girl in the

Window, adapted from the real-life Kuroyanagi’s autobiographical YA novel, which

screens as part of the 2025 New York International Children’s Film Festival.

Totto-Chan

is a classic example of what contemporary audiences might see a gifted student

who becomes inadvertently disruptive due to lack of challenge. In Japan on the

cusp of WWII, most teachers just consider her a pain. Kobayashi gets her and

she thrives under his non-traditional approach. Tomoe also perfectly suits her

empathy and tolerance, because it is there that she meets her (arguably best)

friend, Yasuaki Yamamoto, a little boy whose leg and arm were shriveled by

polio.

She

helps build his courage and learns how to be more sensitive towards others from

him. Unfortunately, very few of her countrymen try to learn greater sensitivity

after the Pearl Harbor Attack. Clearly, her parents have grave reservations

regarding the war, but Totto-Chan instinctively understands the need to keep private

family business private. She quickly recognizes the dangers represented by a

uniform. Totto-Chan is also surprisingly mature when it comes to facing hunger

caused by wartime shortages.

Such

excesses of Japan’s militarism periodically intrude into Totto-Chan’s life, but

the film mostly focuses on her relationships, especially with Yamamoto. When

you really boil it down, this is an absolutely beautifully, almost painfully bittersweet

portrait of young friendship.

Among anime fans, Mobile Suit Gundam is considered the granddaddy of the mecha

genre. Yet, during its initial series run, budget shortfalls constantly forced

producers to cut corners. Series director Yoshiyuki Tomino believed the

economizing was particularly conspicuous throughout the fifteenth episode, so

he withheld it from most subsequent distribution packages. However, he still

believed the story had potential. Years later, this interlude from the Earth

Federation’s battle against Zeon separatists gets a feature-length remake in Yoshikazu

Yasuhiko’s Mobile Suit Gundam: Cucuruz Doan’s Island, which releases

Tuesday on BluRay.

All

you really need to know about the Battle of Jaburo is recent momentum has

favored the Federation, but Zeon has a major game-changing counter-offensive

planned. According to his orders, Captain Bright Noa dispatched Amuro Ray and

his comrades Kai Shiden and Hayato Kobayashi on a “mopping up” operation,

targeted suspected sleeper operatives on Alegranza, perilously near their

Canary Islands base.

Unfortunately,

after the disoriented Ray separates from his unit, he is ambushed by a vintage

Zaku, a Zeon mecha suit. Per protocol, Shiden and Kobayashi must leave him

behind. However, he will not face the sort of peril they fear. Instead, Cucuruz

Doan, the pilot of the Zaku, helps nurse Ray back to help and offers him hospitality

in his farm, a refuge for two dozen or so war orphans.

While

Ray is eager to rejoin the war, Doan has declared his own separate peace. He

bears Ray no ill-will, but he will not do anything that could bring warfighting

back to his island. Consequently, Ray wastes days searching for the Gundam Doan

hid alongside his Zaku. Yet, as Ray comes to know the orphans, he better

appreciates Doan’s desire to protect them and his aversion to the ongoing war.

Of

course, war inevitably returns to Alegranza, whether Doan likes it or not. Having

lost contact with their sleeper operative, Doan, the sinister Zeon commander M’quve

deploys a unit of Zakus to take charge of the doomsday weapon buried in the

island’s subterranean caverns. Ray’s friends are also on their way, since

Captain Noa conveniently feigned engine trouble, to facilitate the unsanctioned

rescue operation he knew they would launch.

The

contrasting ways Ray and Doan relate to war gives this film some intriguing

philosophical heft. It is easy to see why Tomino considered the original

episode lost a lost opportunity. The storyline is also easy to carve out of the

overall series narrative. However, much of the business involving the orphans

is a way too precious.

In Japan, their favorite Jetson must be Rosey, the family’s robotic maid.

That is just a guess based on recent pop culture trends. In a few days, Apple

TV+ viewers will meet Sunny, the Housebot, in the Japanese-set series named

after her. Nanako is an autoboot, but she largely has the same functions.

However, she has a much more sci-fi destiny in Tomoyuki Kurokawa’s Break of

Dawn, which is available on American Airlines international flights (it

never ceases to amaze what you can find on international in-flight

entertainment systems).

Yama

is crazy about space, but not so enthusiastic about robots, at least judging by

his treatment of Nanako. His parents insist she is one of the family, but he

acts like she is merely a kitchen appliance. Annoyingly, his friends like her

too, because it is advantageous to play video games in “autobot mode.”

Suddenly,

while retrieving the errant Yama, Nanako’s system fails. She successfully

reboots, but then February Dawn, an alien AI, takes control over her body. As

Yama and his friends, Shingo Kishi and Gin Tadokoro, soon learn, his ship

crashed on earth over 10,000 years ago. Fortunately, he has gleaned some useful

intel from an errant satellite that took on a mind of its own, after colliding

with a comet. If Yama and his two cronies can retrieve a missing crystal, they

can help him power-up his craft, before it is destroyed, along with the old

Stuytown-like apartment building scheduled for demolition, where it is perched,

apparently invisible to the naked eye.

When

Nanako comes to and beholds the VR-visions February Dawn projects for Yama and

his friends, she agrees to help, even though she is not programmed to deceive

his parents. That might become an issue later. For the meantime, they need that

crystal. They soon discover it is in the possession of Kaori Kawai, an

upperclassman at their school, bullied by Kishi’s mean-girl older sister, Wako.

That too will be an issue. However, the most surprising revelation for Yama

will be the discovery her father and his parents were previously acquainted.

They may even know something about February Dawn.

Retail analysts keep predicting the extinction of the department store. If that

happens, the Hokkyoku Department Store would then match its clientele. Somehow,

the store exists somewhere outside of time. Inside, humans wait on customers

who entirely consist of extinct species. The newest employee is a bit clumsy,

but she is earnest and conscientious. Nevertheless, retail is still tough work

in Yoshimi Itazu’s anime feature The Concierge, based on Tsuchika Nishimura’s

manga, which screens during the 2024 New York International Children’s Film Festival.

Akino

once stumbled into the Hokkyoku as a little girl, finding herself dazzled by

the elegant concierge. Now life (or is it afterlife? The film and manga keep

discreetly vague on that point) has come full circle for her, since she was

hired as the Hokkyoku’s newest concierge. Her colleagues recognize her kind

heart, especially Eruru. Akino thinks he is a customer she literally keeps

stepping on, but he is really the president. He is also a great auk, so don’t

call him a penguin, even though he enjoys sliding across the polished floors of

the mall, as if they were ice flows (which is a pretty cute bit of business).

Unfortunately,

Toudou, the Snidely Whiplash-like floor manager is constantly on her case. The

pressure keeps mounting with each nearly impossible request, like the customer searching

for a discontinued fragrance. Fortunately, a lot of her co-workers are willing

to pitch in to help, including Eruru behind-the-scenes.

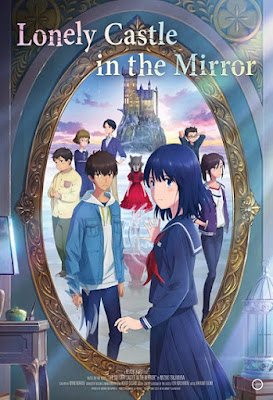

This portal fantasy world keeps bankers’ hours: nine to five, Japanese time.

To get there, seven troubled middle-schoolers literally travel through the

looking glass. What they find is more like a clubhouse than Narnia, but its

rules still need to be respected in Keiichi Hara’s Lonely Castle in the Mirror,

from GKIDS, which screens today and tomorrow nationwide.

Kokoro

has almost entirely stopped attending school, after the bullying she faced

drastically intensified, but she is too ashamed to explain it to her parents. Just

when she really sinks into depression, “Ms. Wolf” pulls Kokoro through her

mirror to a remote, fantastical castle, entirely surrounded by water, where six

other confused middle schoolers are waiting.

They

will have the run of the place until one of them finds a magic wish-granting

key. Once they wish for their heart’s desire, all seven will lose their

memories of the strange castle and of each other. Until then, they can spend as

much time there as they like, as long as they leave by five. If they are caught

after hours, they will be eaten by “the Wolf.”

Slowly,

the seven become friends and discover the secrets they have in common. There

always seem to be exceptions to their conclusions, but there are always good reasons

for them. It is not entirely unfair to think of Lonely Castle as a Breakfast

Club portal fantasy, but there is more to it than that. For one thing, it

riffs on Little Red Riding Hood (Ms. Wolf sometimes even refers to the

seven misfits as her “Riding Hoods”), much in the same way Belle riffed

on Beauty & the Beast.

Daijin considers himself a god, but he looks like a cat and he has a decidedly

selfish, feline-like personality. Unfortunately, he doesn’t just walk on people’s

laps with his penetrating paws. He is determined to open portals that would

allow Namazu, the mythical worm kaiju, to enter our world, like when he caused

the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. It is Sota Munakata’s calling to keep those

doors closed, but he will need Suzume Iwato’s help in Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume,

which opens Friday in New York.

Iwato

is still haunted by the loss of her mother during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake-tsunami.

Since then, she has lived with her Aunt Tamaki on picturesque Kyushu. One day,

while biking to school, she encountered Munakata, who asks if there are any

ruins on the island. In fact, there is an abandoned resort village. Intrigued,

Iwato starts exploring the ruins, trying to find the mysterious door Munataka

mentioned. The surreal looking stand-alone door certainly looks like what he

had in mind, but as she pokes around, she inadvertently releases the “keystone”

sealing the portal.

That

keystone turns into an extremely mischievous cat that calls itself Daijin (sort

of like Daimajin). With Munakata’s help, Iwato barely manages to close the

door, but to keep it closed, they will need to put the keystone back in his

proper place. Daijin leads them on a merry chase across Japan, opening door

after door, with no regard for the death and destruction that could result. Adding

a further degree of difficulty, Daijin also curses Munakata, transforming him

into the old three-legged stool Iwato’s mother hand-crafted for her.

Only

an anime master like Makoto could successfully pull-off a sentient,

self-ambulatory stool, sort of like the Beauty & the Beast candlestick,

but in a contemporary dramatic setting, presented in a serious manner. Indeed,

he pulls it off, while building some truly poignant chemistry between the two

lead characters (even though one of them spends most of the film as a small

piece of furniture). In this case, the relationship between Iwato and Munataka takes

on romantic dimensions, but it is more complex and ambiguous than that of Your

Name, Shinkai’s most comparable previous film.

Legendary Prince Rama and evil King Ravana have appeared in many, many Indian films, even the

superhero movie Ra.One, which is named for the super-villain, a digit

reboot of Ravana. Yet, their story is probably best known to animation fans

through films produced outside India. Nina Paley gave Rama’s loyal wife a

feminist spin in Sita Sings the Blues. Before that, respected Indian

animator Ram Mohan also collaborated with Japanese co-directors Koichi Sasaki

and Yugo Sako to create the classic Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama,

which screens with freshy restored vividness tomorrow at the Japan Society.

Whereas

Paley undercut Rama’s heroics, Mohan and company somehow saved all the best

fight scenes for his brother Lakshman or their friend, Hanuman. The latter happens

to be a mighty flying monkey, so giving him screen time makes perfect sense—but

we get ahead of ourselves.

There is

first Prince Rama’s courtship of Sita and their banishment from her Kingdom of Mithila.

The king had intended to anoint Rama his successor, but he is honor-bound to

grant the two boons requested by his second wife, who insists on Rama’s

expulsion, in favor of her own son’s ascension. Yet, the couple spent many

happy years in the forest, with only Lakshman and a small army of cuddly

woodland creatures for comfort, until evil King Ravana kidnaps Sita for

himself.

This is

where the film really starts getting good. While on the trail of Ravana, Rama

and Lakshman meet Hanuman, who introduces them to his master, Sugriv, who has

been deposed from his own kingdom. Rather pragmatically, Rama restores Sugriv

to his throne, who then mobilizes his army to aid Rama in his quest. However,

reaching Ravana’s island stronghold will be their first logistical challenge.

Then they will face Ravana’s freakishly giant warrior-retainers.

A lot of

Ghibli veterans worked on Ramayana, presumably on the stunning fantastical

vistas and awesome battle scenes. From time to time, there is a bit of

un-Ghibli-anime awkwardness to the characters’ movement, but that sort of adds

an element of nostalgia. Regardless, it is impossible to go wrong with army of

monkey warriors. The second half is like a Planet of the Apes movie,

wherein apes and men work together to fight the hydra-like Ravana and his

batwing minions.

Ramayana

is incredibly respectful of the Sanskrit epic. There

was a bit of controversy in the early going, but the final product became a

symbol of Japanese-Indian cooperation. However, it is still highly watchable

for audiences coming from outside Eastern religious traditions. They definitely

emphasize the fantasy elements to such an extent, you could almost consider it

a Hindu Clash of the Titans (we think of that as a good thing).

Whenever a film invites us to share a group of friends’ last summer together, it is

a near certainty we will see the final summer ever for one of them. Roma Kamogawa

will definitely have his Big Chill moments, but he does not carry any ex-hippy-boomer

baggage, so it is easier to identify with and feel for him in Atsuko Ishizuka’s

anime feature Goodbye, Don Glees!, which screens nationwide over the

coming days.

Kamogawa’s

boyhood friend Toto Mitarai will sort of explain why he named their club of two

the “Don Glees,” but it doesn’t really make sense, so don’t worry about it.

They had to stick together through middle school, but Mitarai’s domineering

father sent him to Tokyo for high school. Now that he is back after freshman

year, Mitarai clearly considers Kamogawa a bit of a towny, which makes him embarrassing.

He is also more than a little put off by Kamogawa’s new friend.

Shizuku

“Drop” Sakuma is somewhat younger than they are, but Kamogawa enjoys his energy

and earnestness (whereas Mitarai, not so much). Unfortunately, their private

store-bought fireworks ritual goes somewhat awry, especially when their snobby

peers point to it, scapegoating them for a freak forest fire. To prove their

innocence, the trio sets off on a quest to find an errant drone they hope

recorded exculpatory footage.

Nobody

does teen angst better than anime filmmakers. This is another good example. Admittedly,

Roma and Toto are a bit dense when it comes to picking up on Drop’s fatalistic

carpe diem asides, but Ishizuka definitely understands the emotional mindset of

young teens. In fact, her story takes on surprising depth and complexity, especially

when it reaches the third act (or maybe it is actually a really long epilogue).

Regardless, she ties everything together beautifully and even hints at the

mildly fantastical.

How many interlocking stories can there be in a nearly post-human dystopian

future? Apparently, there are at least four, but the one most anime fans will

really what to see is the tale contributed by the animator of the Cowboy

Bebop and Macross Plus franchises. Conveniently, Shinichiro Watanabe’s

A Girl Meets a Boy and a Robot screened on its lonesome during the 2022 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Somehow,

the girl managed to stay alive in a desert wasteland, without any

companionship. One day, a robot with amnesia falls out of an automated supply

train. He sort of resembles the Taika Waititi droid from The Mandalorian,

but is less annoying, and has more personality. With his help, they hitch a

train hobo-style to the nearest big city. It is empty too, except for a young man,

who gives her a crash course in evading the robotic tank that outlived its

programmers. He also introduces her to some lore that does not sound very

science fiction-ish, but will motivate the grandly tragic third act.

At

first, Girl Meets appears like a deceptively familiar post-apocalyptic

world, but it takes on big, cosmic dimensions. Watanabe handles the slow

blossoming quite dexterously and many of his visuals are quite compelling,

While the character designs are not wildly original, they definitely resonate

with viewers.

Clearlly, anyone who

appreciates the major anime series (especially those of Watanabe) should enjoy Girl

Meets. Maybe it is even richer when viewed together with the other stories

of Taisu, but as a Chinese production, there is a good chance the

Chinese contributions are compromised from a propaganda standpoint. After all,

the Mainland film industry is closely aligned with the oppressive CCP. Therefore,

seeing Watanabe’s contribution separately at festivals is probably the most

ethical strategy for his fans to watch it. Recommended under these

circumstances, A Girl Meets a Boy and a Robot had its Canadian premiere

at this year’s Fantasia.

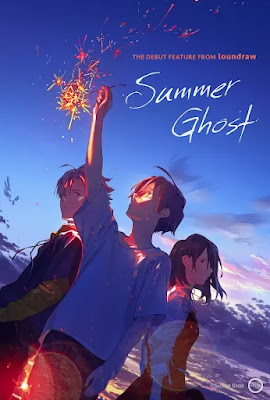

It is a lot more intense growing up in Japan. Think of it this way: how

many of your friends went to cram school? In Japan, it would have been 100% of

those whose parents could afford it. Tomoya Sugisaki is definitely one of them,

but he hates every minute of it. He and two other frustrated teens seek out a perspective

from beyond the grave in Loundraw’s Summer Ghost, which screened during

the 2022 Fantasia International Film Festival.

According

to urban legend, the ghost of a beautiful young woman appears when the curious

set off fireworks on a summer evening. Although he is a loner, Sugisaki

connected online with two other teens who share his fascination with the

so-called “Summer Ghost.” An abandoned airstrip looks like the perfect place to

summon her, which indeed it turns out to be.

The

girl was Ayane Sato. Contrary to popular belief, she did not commit suicide.

Instead, she was killed in a hit-and-run, by a driver who subsequently dumped

her body in an unknown location to cover-up the crime. Sato explains it is not

just fireworks that are necessary to see her. Seekers also need to be mentally

closer to death. Indeed, Sugisaki and the bullied Aoi Harukawa are having

distressingly dark thoughts, while Ryo Kobayashi is dealing (badly) with a

fatal diagnosis.

Sato

is definitely a ghost in the tradition of When Marnie was There, rather

than a horror-style apparition. It is enormously sad and tragic, but also

ultimately humanistic and life-affirming. The teens’ drama is totally grounded

and true-to-life, while the ghost business is quite tragic, in a lovely kind of

way.

Maise Higa feels like a towny working in her parents Okinawa resort hotel, but

a lot of teenagers would probably consider it a pretty cool summer job,

especially when attractive Ichiro Suzuki checks in. He is not the baseball

player, but Higa is sure he is famous from somewhere. Regardless, she is

definitely interested in him, despite the weird events that start happening

around him in Ushio Taizawa’s 13-mini-episode micro-series, which screened in

its entirety during the 2022 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Higa

is embarrassed by her family (except her grandmother), because she is a

teenager. She can’t help noticing Suzuki has that brooding James Dean thing

going on, but she just can’t place him. Nevertheless, she must respond to some

unusual room service calls when the hotel first floods like a fish bowl and

then becomes entwined in a giant Jack-and-the-beanstalk-like tree. In both

cases, she traces the fantastical source back to his room.

Fortunately,

these incidents never disrupt the hotel’s service for long. They must have some

fantastic insurance. Higa also starts developing ambiguous feelings for Suzuki,

even though he seems to be somehow causing all the hassle. Something about his melancholy

touch her.

Yes, all parents are embarrassing, but Nikuko is in a league of her own. Yet,

her daughter Kikuko never judges her too harshly, because she understands her

better than even her mother realizes. Life dealt Nikuko a lot of

disappointments, but at least she has her daughter in Ayumu Watanabe’s Fortune

Favors Lady Nikuko, from Studio 4ºC and GKIDS, which screens nationwide

tonight (and opens Friday in select theaters).

Big-hearted

and big-boned Nikuko has a long history of getting involved with the wrong men,

who inevitably took advantage of her. The last was arguably the best of the bad

lot, so Kikuko sort of understood when her mother dragged her to his sleeping

fishing village-hometown, afraid he had fled there to take his own life. They

never found him, but they decided to stay and make a home there.

Nikuko

works for the gruff but protective Sassan at his seafood grill and they rent

his ramshackle houseboat. Boys are not really a factor yet in tomboyish Kikuko’s

life, but she is reasonably friendly with her fellow girls at school. In fact, she

is courted by two basketball-playing cliques, because of her height, but she is

uncomfortable committing to either side. However, her anxiety is probably

really coming from a fear Nikuko will uproot them again.

Despite

being a slice-of-life story (think of as a Japanese Beaches, but with

less weepy melodrama), Lady Nikuko features some wonderfully vivid

animation. The coastal village and surrounding environment sparkle on-screen

quite invitingly. (It is easy to believe this came from the same animation house

that brought us Tekkonkinkreet.) Ironically, there is a far more visual

dazzle in this film than Watanabe’s more fantastical Children of the Sea.

It is highly unlikely we will wake up to find this film is an Oscar

nominee, even though it is fully qualified as an animated feature. However, of

the two remakes of the 2003 Japanese film (itself based on Seiko Tanabe’s

children’s book) produced in 2020, this film has had a much higher North

American profile than its live-action Korean competition. Instead of mecha, the

anime drama revolves around teenage insecurities and understanding physical

differences in Kotaro Tamura’s Josee, the Tiger, and the Fish, which

releases today on BluRay/DVD.

Tsuneo

Suzukawa is a dirt-poor, hardworking marine biology student who harbors

ambitions of attending an expensive summer program in Mexico, to study a rare

breed of tropical fish that always fascinated him. It sort of seems like good

fortune when Chizu Yamamura hires him to be a companion-helper to her

wheelchair-bound granddaughter Kumiko, except for her demanding personality. She

prefers to be called “Josee” and has real artistic talent, but she treats him

like a rented mule.

Of

course, that means she is really in love with him and he feels the same about

her, but neither can admit it to themselves or each other. They might lose

their chance when serious hard times come around. (By the way, she will

eventually draw a tiger rife with symbolic significance, if you were wondering

about the rest of the title.)

Josee

etc. follows

in the tradition of A Silent Voice’s heartfelt teen drama and sensitive handling

of physical ability issues, but it is not nearly as adroit at handling either. Sayaka

Kuwamura’s adaptation of Tanabe means achingly well, but it lays on the angst

with a trowel. While Voice pulls the audience in and makes them care, JTF

often leaves us feeling manipulated.

Our juvenile hero is a chimney sweep, but this is not a cute, upbeat

musical, like Mary Poppins. It is dystopian anime. Apparently, Chimney

Town was conceived as a utopia, but it turned into a dystopia, as utopias

necessarily always do. Yet, earnest young Lubicchi just might save his society

from its fears and ignorance in Yusuke Hirota’s Poupelle of Chimney Town,

produced by Studio 4ºC, which opens in limited release this Thursday, for Oscar

qualification.

Poor

Lubicchi must constantly sweep the smokestacks belching smoke over his

steampunky city, because he is the sole support of his wheelchair-bound mother,

since the death of his beloved father. When he was alive, Bruno used to tell

stories about stars in the sky and other lands beyond the sea, but everyone assumed

they were fairy tales—except Lubicchi. He is still bullied over his father’s

stories, but Lubicchi could potentially face harsher repercussions from Chimney

Town’s inquisition, which does not take kindly to such heresy.

One

magical Halloween, a mysterious, cosmic heart lands in a landfill, where it

assembles and animates a literal “junk man.” Naturally, the fearful and

provincial townspeople shun him, but he finds a friend in Lubicchi, who dubs

him “Poupelle.” Of course, the Inquisition wants to capture the “man of junk,”

but they evade the theocratic enforcers, with the help of Scoop, a

thrill-seeking Libertarian tunnel pirate. Together, they might even prove the existence

of stars.

In

fact, the film, based on a children’s book written by Japanese comedian Akihiro

Nishino, is fairly Libertarian, even though it is based on an economic fallacy.

Supposedly, Chimney Town was created by a cult devoted to an economist, who

invented money that decays for the sake of economic equality. Of course, our

money also gets rotten over time. It is called inflation and lately the rate of

decay has been blisteringly fast—and it has been working families like Lubicchi’s

that are hurt most.

Religious parables used to share a thematic affinity with the fantasy genre, with

all the swords and sandals. Increasingly, they are shifting to science fiction—and

it isn’t just Battlefield Earth. The controversial Japanese religious

fusion movement Happy Science has become a regular producer of anime features. The Mystical Laws happened to be a pretty entertaining sf-geopolitical-conspiracy

thriller, but the conflict plays out on a more galactic scale in director-chief

animator Isamu Imakake’s The Laws of the Universe: The Age of Elohim,

which screens tomorrow at the Laemmle NoHo 7 (and opens October 22 in New

York).

This

is Earth, but you wouldn’t recognize the place 150 million years ago. Elohim,

the God of Earth (formerly known as Alpha) benevolently rules over the planet,

which offers sanctuary and the potential for reincarnation to all races of the

universe. The Dark Side of the Universe does not appreciate such values, so the

malevolent titan Dahar manipulates Evol, the ape-like military leader of Centaurus

Beta into waging war on our planet.

Yaizel,

the champion of planet Vega is dispatched to rally Earth’s defenses, just in

the nick of time. As the forces of evil (and Evol) mass for an invasion,

Sagittarius also sends reinforcements to Earth in the form of seven archangels,

including Amor (who looks a heck of a lot like J.C.), Michael, and his brother

Lucifer, who does indeed seem to be rather arrogant.

Frankly,

it was hard to tell what Mystical Laws was proselytizing, which is why it

was so watchable. In contrast, it is easy to pick out the precepts and

principles in Age of Elohim (how could you not?). The narrative, written

by Sayaka Okawa, but based on the ideas of Happy Science founder Ryuho Okawa,

is not exactly an origin story, but it is definitely an explain-how-things-came-to-pass

parable. However, the animation looks first-class and there is still a lot of action.

Shinji Ikari's father issues are pretty extreme. Gendo Ikari has done his best to

sever all connections to his son, while leading a shadowy conspiracy to destroy

the world and re-create humanity into a single collective consciousness. Yet,

you could say “like father, like son,” since Shinji has almost inadvertently

destroyed the world, not once, but twice. That is a lot for one young person to

bear. Not surprisingly, the angst-ridden mecha-pilot is not holding up well in creator-chief

director Hideaki Anno’s Evangelion 3.0 + 1.01: Thrice Upon a Time, the

[most likely] concluding film of the Rebuild of Evangelion reboot series,

which premieres Friday on Amazon Prime (with a title like that, you know it

must be an anime feature).

As

the film opens, Shinji Ikari is so guilt-ridden, he has practically shut-down

his body and spirit. He has been shipped off to a peaceful countryside

community of survivors to recuperate, along with his fellow EVA pilots, Asuka

Shikinami Langley (who both resents and carries a torch for Ikari) and Rei

Ayanami (a clone of a clone, quietly imploding worse than Shinji).

Of

course, this interlude cannot last. Eventually, Ikari and Langley will return

to WILLE, the global defense agency led by Misato Katsuragi, who was something

like a surrogate mother to Ikari. They first met while they were serving NERV,

ostensibly WILLE’s forerunner, which was secretly founded by his father to

hasten the final, world-shattering “Impact.”

Obviously,

it is time for the final battle (at least until the next one), to be fought by Katsuragi

helming the WILLE fleet, including EVAs piloted by Shikinami and her gifted comrade,

Mari Illustrious Makinami (for whom Ikari might carry a torch) against the

vastly greater forces of NERV. Eventually, Ikari will also have to face his

father, EVA-to-EVA, in Minus-Space, where the rules of physics and scale measurement

do not apply.

There

are some anime series that get pretty apocalyptic, but Thrice Upon a Time tops

them all. It also outdoes all the competition when it comes to neurotic angst.

Yet, that really makes 3.0+1.01 a fitting capstone to the series. Once

again, Anno’s team delivers visuals that are three or four cuts about the

series anime standard. The prologue battle above a ruined Paris is particularly

striking. Arguably, the first act idyl in the village drags out a bit, but it

ends on a potent note that is ever so true to the spirit of the franchise.