It is supposed to be dystopian, but this near-future Japan is largely already the

present day in Mainland China. Essentially, the system of social credit and the

intrusive surveillance to enforce it comes to Kou’s high school. Unfortunately,

he and his friends always lack every just about every form of credit, as the

children of immigrants (mostly Korean). The world is truly falling apart, but

the principal still won’t cut them any slack in director-screenwriter Neo Sora’s

Happyend, which opens Friday in theaters.

The

scariest thing about Happyend is that you might not realize its

dystopian if you weren’t told upfront. Frankly, people in Tokyo have a right to

be a bit on edge, because the big cataclysmic earthquake could come any day

now. The scumbag PM tries to deflect and distract by cracking down on Zainichi

Korean population. That makes life even harder for Kou and his friends and

family.

Kou

might be the only one with the chance to attend college. Of course, he needs a

scholarship, so he finds himself dependent on Principal Nagai for a recommendation,

which the ostensive educator will not let Kou forget. Awkwardly, Nagai is on

the warpath against Kou’s ambitionless best friend Yuta, whom he suspects was

behind the impressive prank that balanced his sportscar on its rear bumper—which

indeed he did, with Kou’s reluctant help.

It is interesting

to compare Happyend with the recently re-released Linda Linda Linda, because

both films capture teenage friendship on the cusp of graduation. However, Sora

makes every mistake the 2005 cult classic nimbly avoids. While the punk rock

coming-of-age story shrewdly avoids politics, Sora doubles, triples, and

quadruples down. Awkwardly, he settles on immigrant discrimination as his

dominant theme, which is a shame, because most of his points are familiar and

predictable. In contrast, some of his pointed critiques of the Big Brother

surveillance apparatus are quite clever. The cameras and AI might see all, but

they are blind to context.

Admittedly, these two teens are about to die, but don’t think of it as a downer.

This way, the lucky cousins will learn their purposes in life—short though they

were. Yet, unlike Robin Williams in What Dreams May Come, they might be

able to return to their interrupted earthly lives, so they apply their epiphanies

with their memories intact—maybe, just maybe. Unfortunately, their journey of self-discovery

entails more than just one trip to Hell. They must visit several in Isamu Imakake’s

Happy Science-produced Dragon Heart, which opens this Friday in Los

Angeles.

Blame

the kappa, who lured Tomomi Sato and her visiting cousin, Ryusuke Tagawa into

treacherous currents. Apparently, that was that, but Ameno Hiwashino Mikoto,

the god of the local Shinto shrine invites them to explore the spirit realm.

Much to their surprise, the tour quickly takes on Divine Comedy parallels.

First,

they materialize in a violent gangster world, where the damned constantly murder

each other. From there, they fall into a bizarre Lynchian hospital, which

dispenses a distinctly sinister variety of care, very much in the surreal

tradition of Inoperable or Fractured. It is a nightmarish place, yet

it is also where they witness the redemption and rescue of a tormented soul. That

plants a seed with Sato and Tagawa, giving them a notion this might be

something they want to do.

However,

it will take some doing before they can start saving souls. To get to that point,

they must escape from a snake queen and find the hidden enclave of Shambhala to

start their advanced spiritual training.

Dragon

Heart is the

latest anime feature based on the teachings of the Happy Science movement. In

terms of the level of proselytization, this film falls somewhere between The Mystical Laws and The Laws of the Universe: The Age of Elohim. There

are times when the spiritual content feels very heavy-handed. Yet, the uninitiated

would be hard-pressed to explain the film’s foundational doctrines, beyond

generalities like believe on God and recognize the soul is man’s true form rather

than the body. Indeed, for pagans, the film seems to freely mix Shinto, Buddhist,

Hindu, and Christian symbolism, cafeteria-style.

Regardless,

the level of animation remains surprisingly high. Imakake worked on several

major anime properties prior to helming Happy Science’s animated features

(including Cowboy Bebop, Evangelion, and Lupin III), so the level

of animation is always professional grade. In fact, many of fantastical

landscapes are really quite visually striking.

It is a term rich with anime and folkloric significance. “Mononoke” are vengeful spirits,

not unlike yokai. Miyazaki’s “Princess Mononoke” was not really a mononoke, but

rather a human foundling who had a rapport with spirit creatures. The mononoke

of the Mononoke anime and manga franchise are definitely mononoke. In

fact, they are about as mononoke as they get. It is the “Medicine Seller’s”

calling to exorcise them. Think of him as a medicine man, in that he holds

shaman-like powers and peddles medicinal cures. He cuts an odd figure, but even

the most secretive and powerful players in the Edo court will not turn him away

when an enraged spirit terrorizes their Lord’s harem chambers in Kenji Nakamura

& Kiyotaka Suzuki’s Mononoke the Movie: Chapter II—The Ashes of Rage,

produced by Toei Animation, which premieres today on Netflix.

Thanks

to the Medicine Seller, the Lord Tenshi’s concubines already survived one

incredibly put-out mononoke in the previous film (which was a continuation from

the 2007 anime series). Unfortunately, just when you thought it was safe to go

back to harem’s super-restricted Ooku, another mononoke strikes. Obviously, the

Medicine Seller needs to investigate, but his all-access pass is no longer

valid, because it was issued by the former Ooku manager—now deceased.

Tensions

were rising in the Ooku, even before the new mononoke peril emerged. The unseen

Tenshi’s favorite, Fuki Tokita is showing signs of pregnancy, which should be a

good thing, because an heir is needed. However, Tokita hails from “common stock,”

even though we would probably consider her family middle to upper-middle class,

from out contemporary perspective. Regardless, the prospect of debasing the

Imperial lineage with common stock and allowing a less than pristinely noble

family that kind of influence has the elite power-brokers alarmed.

Botan

Otomo is perfectly placed to take action. She was selected to serve as the new Ooku

manager because of her family’s power and prestige. As Tokita’s longtime rival,

she openly resents Fuki’s inappropriately close relationship with Tenshi.

However, she also feels loyalty to her Imperial lord and his prospective heir,

whoever it might be. Instead, it is the angry mononoke of a wronged concubine

who terrorizes the Ooku halls. Yet, before the Medicine Seller can dispel it,

he must learn the reason for its grudge—much like Christian exorcists need a

demon’s name to take dominion over it.

Without

question, Nakamura’s Mononoke films represent an energizing respite from

overly slick (and consequently soulless) 3D computer generated animation. While

digital techniques were employed, the Mononoke features have an eye-popping,

mind-blowing baroque style that resemble a fusion of Edo-era ukiyo-e woodcuts

with Peter Max headshop posters. Each frame is an absolute explosion of color.

Frankly, it is a good thing Ashes of Rage is a relative shorty, because extended

exposure to the utterly distinctive animation could induce sensory overload.

Yet, it is always wildly cool to behold.

Its a ghostly buddy comedy, sort of like All of Me, but with some seriously “anti-social”

behavior. Hideo Kudo was an elite hitman with a shadowy syndicate—with the

emphasis on the “was.” Now he is dead, murdered by his former associates. However,

he still has his deadly skills, when he borrows Fumika Matsuoka’s body. He is

an extremely angry ghost, but their partnership makes him a more decent soul in

Kensuke Sonomura’s Ghost Killer, which releases today on digital.

Kudo

was hard to kill, but eventually they got him. The operation is perfectly

executed, but the clean-up crew misses the cartridge casing. When Matsuoka, a distressed

college student, picks it up, her resentments combine with Kudo’s grudge to

produce a haunting. To get rid of him, she must allow him to take over her body,

to extract his vengeance. However, he first spends a good deal of time beating

the snot out of her would-be abusers.

In

fact, things get so messy, Kudo must call in help from his protégé Toshihisa

Kagehara, to tidy up all the moaning and groaning bodies. Of course, Kagehara

has only one method of cleaning, which poor Matsuoka does not want to think

about. Regardless, Kagehara is way too edgy to fully trust.

You

often see the me-and-my-ghost premise in comedies, but Ghost Killer is

surprisingly dark. It also kicks tons of butt. Sonomura served as his own fight

director and he did not pull any punches. It is one gritty but spectacularly

cinematic beat-down after another.

This is sort of the Tokusatsu (Japanese genre-action series) analog to Mustafa: The

Lion King. In the original Garo tv series. Taiga Seijima had already

been killed by the student who betrayed him, leaving behind his son Kouga to

succeed him as a Makai Knight—the mystical warriors who bravely battle the

so-called “horrors,” or demons that have assumed human bodies. However, that fateful

day will not be today. During this prequel, Taiga Seijima is still young,

cocky, and very much alive. To celebrate the franchise’s 20th

anniversary, series creator Keita Amemiya rewinds back to the senior Seijima’s early

days (which look very much like the current day) in Amemiya’s prequel feature Garo:

Taiga, which had its world premiere at this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Sure,

the basic concept of brotherhood of secret warriors sworn to protect the world

from evil supernatural forces maybe sounds a little familiar, but Amemiya has

been doing this for twenty years now. Before that, he created the Zeiram franchise

and made significant contributions to Kamen Rider, so he knows

Tokusatsu.

At this

point, Seijima and his talking skull ring are tearing it up as horror hunters,

but their next case (after the prologue) will be much more difficult. Evidently,

a seriously powerful horror blew into town, on a mission. “Snake Way” intends

to consume the four “Sacred Beasts” and take their powers, even though a horror

ordinarily cannot gobble up elemental gods. Yet, they can swallow up humans.

Inconveniently, Byakko, the wind deity, has a habit of breaking out of his mystical

safety-deposit box to enjoy the simple joys of assuming human form.

As a

prequel, Garo: Taiga is relatively accessible to newcomers, but it helps

to have an appreciation of the Tokusatsu aesthetic. Basically, it is a cut

above the non-Shin theatrical Ultraman movies that traditionally

conclude each season. It is undeniably cheesy to watch Taiga strut through the

city in his big hair and long white Adam Ant-ish duster, but it is a polished

cheese.

Ryosuke Yoshii is the kind of reseller who has a one-star rating on ebay (or it is fictional

equivalent). Yet, people still buy from him. Big surprise—they often regret it.

Unfortunately for him, some of his disgruntled suppliers and buyers start

getting organized “in real life” in director-screenwriter Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cloud,

which opens tomorrow in New York.

It is

easy to see why Yoshii has so much bad karma from the first transaction Kurosawa

depicts. Having commissioned a run of counterfeit medical devices, Yoshii

renegotiates for a fraction on the Yen, because it would cost the small

workshop more to have them carted away as rubbish. Then he sells the entire run

to desperate buyers, even though they are worthless.

These sharp

practices led to the creation of a large network of online haters. Starting to

feel the heat, Yoshii uses his next big score to relocate to the countryside. Nevertheless,

Yoshii fears some of his shadowy stalkers followed him to the boonies.

Increasingly paranoid, Yoshii’s emotional withdrawal pushes away his girlfriend

Akiko. He also fires his new assistant, Sano, but the former protégé remains

loyal to Yoshii, for reasons that are never fully explained. Dano also happens

to have a certain set of skills, honed during his previous employment as a

Yakuza enforcer.

Eventually,

Cloud morphs into a reasonably effective stalker-payback thriller. Nevertheless,

it is remarkable how far this film coasted on Kurosawa’s reputation, including

its selection as Japan’s international Oscar submission. Most viewers who are

unaware of its pedigree would assume it is merely a small, grungy exploitation

movie, because that is exactly how it presents itself. Indeed, this film is

small in scope and rather shallow. However, the concluding action sequence is admittedly

lean, mean, and relentlessly tense.

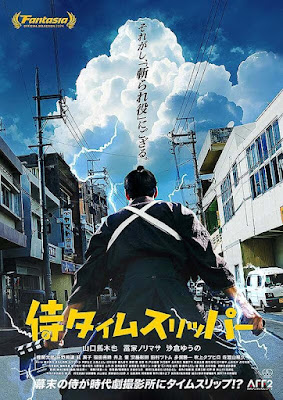

If an Old West gunslinger traveled forward in time to 1950’s Hollywood, he would

probably find steady work as a stuntman. It would be a lot harder for him in

today’s film industry. That is also true for Kosaka Shinzaemon. He was, and remains

a real deal samurai from the Aizu Domain, who somehow traveled forward in time

to the Kyoto Uzumasa studio, where most of the Japanese entertainment industry’s

Jidaigeki samurai dramas have been filmed. It is a whole new era for him, but

he retains some adaptable skills in director-screenwriter Jun’ichi Yasuda’s A

Samurai in Time, which screens as part of the 2025 Japan Cuts festival.

It was

a dark a stormy night. Frankly, Shinzaemon really didn’t notice the stormy part

until he started clashing swords with Yamagata Hikokuro, a rival from the Choshu

Domain. Suddenly, a flash of lightning strikes and there he is on the Kyoto

backlot. Confusingly, half the people look normal, but the rest appear to wear

strange foreign garb. He is a bit of a bull in a China shop, but Yuko Yamamoto,

a conscientious young assistant director looks out for the presumed amnesia

case.

Thanks

to her, he finds a place to stay at the nearby shrine frequently used as a

location. He also starts apprenticing with Sekimoto, a master of

stunt-performer swordplay. Sekimoto warns his new apprentice that Jidaigeki

productions just aren’t as popular as they used to be. Nevertheless, Shinzaemon

becomes a regular stunt performer on Yamamoto’s series, because he just looks

so authentic. In fact, he even draws the attention of Kyoichiro Kazami, a

veteran movie star, hoping to reinvigorate the Jidaigeki genre. Indeed, Kazami

shows a particular interest in Shinzaemon.

Samurai

in Time might remind

genre fans of Ken Ochiai’s loving tribute to Jidaigeki extras, Uzumasa Limelight,

with good reason. Ochiai’s star, longtime Jidaigeki bit-player Seizo Fukumoto was

originally cast as Sekimoto, before his unfortunate passing. Instead, his “junior”

colleague, Rantaro Mine, plays the role with the kind of dignified gravitas Fukumoto

brought to Limelight. So yes, the two films would pair nicely.

In the future, AI will take a huge bite out of psychics’ séance business. If you have unresolved

questions for your late loved ones, like emotionally stunted Sakuya Ishikawa,

just download their data and ask the resulting AI construct. Of course, more input

results in a better model, so Ishikawa requests the data from the close friend

he never knew his mother had. Ironically, the mystery woman might (or might

not) also be his tragic high school crush. Consequently, Ishikawa will have a

lot to process himself in Yuya Ishii’s The Real You, which had its North

American premiere at the 2025 Japan Cuts.

There

was something Akiko wanted to tell Ishikawa, but he was too busy to listen.

Then she died, apparently throwing herself into the swelling river one stormy

night. Ishikawa tried to save her, but instead, he suffered a year-long coma.

When he woke up, the government cut him a check, because unbeknownst to Ishikawa,

his mother enrolled in a voluntary euthanasia program, much like that depicted

in Plan 75.

Tormented

by guilt and uncertainty, Ishikawa uses his savings to commission a virtual

figure (VF) of his mother. It is through the company’s research that he learns

of Ayaka Miyoshi. Strangely, she bears an unlikely resemblance to a high school

classmate, whose misfortune indirectly led to Ishikawa’s downfall (through

circumstances that Ishii teases out agonizingly slowly).

Regardless,

Ishikawa invites the homeless Miyoshi to temporarily move into the apartment he

shared with his mother, out of filial loyalty (and perhaps other reasons). He

starts to get some kernels of truth from Akiko’s VF, but it is unclear whether

he can handle the truth.

Awkwardly,

The Real You consists of two thematically-distinct halves, one of which

is much more compelling than the other. Ishikawa’s halting attempts to better

understand his late mother are often poignant and fascinating, even though they

revisit some of the terrain explored in the vastly superior Marjorie Prime.

Unfortunately,

Ishii devotes equal or greater time to Ishikawa’s travails as a “real avatar,” essentially

a live-streaming gig-worker, who are regularly forced to humiliate themselves

and possibly even commit crimes, to satisfy the whims of their clients.

Frankly, these sequences violate existing laws and any remaining remnant of

common sense. They are also blatantly manipulative and cringe-inducingly

didactic.

They were

like an early Meiji Era Dirty Dozen except there were only eleven of them. In

fact, the so-called “Suicide Squad” were initially only ten condemned prisoners

who agreed to fight for the Shibata Domain, but somehow, they will add one more.

They will need the reinforcements to hold the fort (literally) in Kazuya Shiraishi’s

11 Rebels, which releases today on DVD and VOD.

Masa

was condemned for killing the Shibata samurai who attacked his wife, so as far

as he is concerned, the rest of the clan can go die a fiery death. Nevertheless,

Natsu the lady arsonist (who is stuck with all their domestic chores),

convinces him to join the others “rebels,” to gain his freedom and provide for

his wife.

It will

be a motley crew, including the hulking serial killer, a defrocked priest, a

village madman, and Koshiba, an old man, who, ironically happens to be the best

swordsman of the lot. Ostensibly, they fall under the command of a handful of

Shibata samurai, including the young and honorable Washio Heishiro and duplicitous

Irie Kazuma. However, the Rebels take command of themselves once they discover

Kazuma and Mizoguchi Takumi, the chief retainer, intend to betray them after the

battle. That definitely prompts an “I told you so” moment from Masa, but the rebellious

Rebels are still the only protection their village has from the approaching

Imperial army.

The

mayhem of 11 Rebels is not quite as spectacular as that of Miike’s 13 Assassins, but it is still pretty impressive. (To be fair, they also have

two fewer rebels than assassins.) Jun’ya Ikegami’s screenplay was inspired by

an unproduced and now lost screenplay written by Kazuo Kasahara way back in the

1960s. It is definitely dark, but its tragic heroism nicely taps into the concept

of the “Nobility of Failure” popularized in academic circles by Ivan Morris. If

you don’t really care about that, rest assured there are plenty of cool martial

arts battles.

Regrettably,

one of the best ways to damage an “Amazon”-like corporate behemoth, especially

one that prides itself on its “customer-centric” values, is through those

customers. Survivors tend to leave very bad reviews when their packages

explode. That has been happening throughout Japan on the worst possible day,

Black Friday, in Ayuko Tsukahara’s Last Mile, which is now available on some

international Delta flights.

Despite

its record high volume Amazon’s Daily Fast’s Kanto warehouse has a troubled

reputation, so Japanese expat Erana Funado was dispatched back home from

corporate HQ to whip it into shape—on the busiest day of the year. Her chief

lieutenant, Ko Nashimoto does not seam to mind being passed over. Yet, he represents

the only management team member still employed at Kanto since the incident to

be revealed later.

It is

safe to assume someone else still remembers and remains upset over it. That tragedy

emerges as the prime motive in a string of Amazon Daily Fast shipments

that were rigged to explode. Strategically, many of the bombs targeted

shipments of Amazon’s Daily Fast’s new proprietary smart phone. Given

the season, there are hundreds of temp workers clocking into the Kanto facility,

but the security precautions make it nearly impossible to smuggle in explosions.

Indeed, the cops are baffled, leaving Funado and Nashimoto the best bets to

solve the crime.

It

makes sense Delta chose Last Mile for their in-flight entertainment,

because nothing is more fun than a thriller about concealed bombs while you are

sealed in an airliner flying over the ocean. This one is just okay, but it is extremely

zeitgeisty. Quickly, the investigation focuses on the Sheep shipping company,

from which Amazon Daily Fast has extorted huge discounts, thanks to

their monopsonistic buying power. Of course, those concessions naturally come out

of driver compensation.

So, Last

Mile (a reference to the final leg before a package reaches its recipient)

might not turn up on Prime anytime soon. The two-hour plus running time is

also excessive. Yet, Akiko Nogi’s screenplay clearly reflects the abiding Japanese

interest in corporate culture and teams, as exemplified by kezai shosetsu Japanese

business novels.

Fittingly,

Funado is the most intriguing character, because her corporate loyalty is often

open to interpretation. Her resourcefulness is also impressive. Hikari Mitsushima

brings a lot of screen charisma to the lead role, without overplaying the cloying

pluckiness. It is easy to believe the more laidback (but comparatively underdeveloped)

Nashimoto could work with her.

You

know BJ must be a noir kind of guy, since he is a blues singing detective.

Frankly, he is more of a blues-rocker than blues singer. He is not much of a

detective either, but he keeps pursuing his best friend’s murderer even though

it clearly involves the local crime syndicate in Eiichi Kudo’s Yokohama BJ

Blues, which is now streaming on OVID.tv.

BJ had must

tread lightly investigating his latest case. Akira Kondo’s mother hired him to

find her missing son. Unfortunately, the boss of “The Family” “recruited” Kondo

to be his “companion,” whether the young man likes it or not. There is little

BJ can do, but at least he steals all the toilet paper from the boss’s bathroom

on his way out.

While

BJ avoids direct conflict with the Family, his friend, Det. Muku, made too many

compromises. Facing imminent arrest for corruption, Muku hopes to bust an

upcoming drug shipment to further bolster the plea deal he is already

negotiating. Unfortunately, he is shot while meeting BJ. Despite a lack of

forensic evidence, Muku’s thuggish partner Beniya tries to pin the murder on

BJ.

Reportedly,

star Yusaku Matsuda was inspired by trailers for Friedkin’s Cruising,

which is highly believable given the tone of the final film. In fact, it is a

miracle the cancel crowd has yet to attack Yokohama BJ Blues for being “problematic.”

However, real people will appreciate the way Kudo makes Yokohama’a seamy red-light

district look grimy and dangerous, as it surely was in 1981.

Matsuda,

who was then at the height of his popularity as the star TV detective series,

rather defiantly plays against type, turning BJ into a decidedly anti-heroic

and thoroughly degenerate gumshoe. Koji Tanaka adds a tragic dimension to the

film as the much-abused Kondo, who secretly befriends BJ.

In the Hatsune

Miku: Colorful Stage “rhythm game,” virtual singers are sort of like the

literary characters who come alive in Twilight Zone episodes, except it

is a relatively common phenomenon. Supposedly, if real-life singers perform

with enough emotion, they can bring their virtual collaborators to life and

even join them in “Sekai,” special dedicated rooms in the dimension between the

IRL and virtual worlds. Weirdly, several bands and their virtual “Mikus”

encounter a mysterious new Miku who cannot connect musically in Hiroyuki Hata’s

anime feature, Colorful Stage! The Movie: A Miku Who Can’t Sing,

produced by animation house P.A. House and released by GKIDS, which starts a

limited 4-day theatrical release today.

Move

over Minecraft, because Hata and screenwriter Yoko Yonaiyama managed to

adapt a game not unlike Guitar Hero or old-fashioned karaoke. However,

there was a large cast of pre-existing characters whom Yonaiyama assumed the

audience would already know. There is a bit of catching up to do, but astute

viewers will hopefully pick things up as they go.

Several

bands have connected with the own virtual collaborators in their specific Sekai.

For Ichika Hoshino that would be Hatsume Miku, who is about the purest

incarnation of a j-pop idol as you could envision. One day, she also encounters

a new Miku, who looks somewhat similar, but is much less self-assured. She

seems to travel through digital screens, producing static and distortions. Ironically,

the frustration caused by her service disruptions makes new Miku’s challenge to

connect on an emotional level even more difficult.

Nevertheless,

the four bands she reaches out to do their best to help, but they cannot

coordinate their efforts, because the alternate Miku communicates with them on

different wavelengths, or something like that. They feel for her and the

creators she is supposed to be attuned with. Unfortunately, the real-life

people hardwired to her Sekai cannot reach it, because they are all mired in

states of creative and emotional crisis. In fact, their aggregated depression

could drag the new Miku down as well.

It

bears repeating, the rules of the Colorful Stage world are a tad

confusing for newcomers, but that is the general idea. Regardless, it is pretty

impressive how Hata and Yonaiyama built a full feature length narrative out of

a smart-phone game that previously spawned a dozen or so ultra-mini anime

webisodes.

While

there are some thematic similarities with Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle, Colorful

Stage! The Movie serves up some interesting world-building. In fact, it

would nicely fit with Belle, Summer Wars, The Matrix, Tron, and

World on a Wire in film series exploring the porous border between the physical

and digital worlds.

The

Tomoe Academy was not exactly A.S. Neill’s Summerhill, but it was quite progressive

for its era. That would be the Tojo Era. Tetsuko Kuroyanagi’s parents were relatively

modern and somewhat Westernized, putting them a little out of step. Little

Kuroyanagi (a.k.a. Totto-Chan) also happens to be a free-thinker, which causes

her trouble at most schools. However, Tomoe’s Principal Kobayashi can handle

her just fine in Shinnosuke Yakuwa’s Totto-Chan: The Little Girl in the

Window, adapted from the real-life Kuroyanagi’s autobiographical YA novel, which

screens as part of the 2025 New York International Children’s Film Festival.

Totto-Chan

is a classic example of what contemporary audiences might see a gifted student

who becomes inadvertently disruptive due to lack of challenge. In Japan on the

cusp of WWII, most teachers just consider her a pain. Kobayashi gets her and

she thrives under his non-traditional approach. Tomoe also perfectly suits her

empathy and tolerance, because it is there that she meets her (arguably best)

friend, Yasuaki Yamamoto, a little boy whose leg and arm were shriveled by

polio.

She

helps build his courage and learns how to be more sensitive towards others from

him. Unfortunately, very few of her countrymen try to learn greater sensitivity

after the Pearl Harbor Attack. Clearly, her parents have grave reservations

regarding the war, but Totto-Chan instinctively understands the need to keep private

family business private. She quickly recognizes the dangers represented by a

uniform. Totto-Chan is also surprisingly mature when it comes to facing hunger

caused by wartime shortages.

Such

excesses of Japan’s militarism periodically intrude into Totto-Chan’s life, but

the film mostly focuses on her relationships, especially with Yamamoto. When

you really boil it down, this is an absolutely beautifully, almost painfully bittersweet

portrait of young friendship.

It is

not simply a question of crumbling infrastructure. Admittedly, alcohol was a contributing

factor, but someone might have intentionally “helped” Shunsuke Kawamura fall

through a manhole, into a narrow subterranean cavity. However, his strategy of

crowd-sourcing his rescue risks igniting the “madness of crowds” in Kazuyoshi

Kumakiri’s #Manhole, which premieres today on Screambox.

Up

until now, Kawamura led a charmed life. Tomorrow, he will marry his boss’s

daughter, so the firm took him out to celebrate. The next thing he knew, he

fell through this hole. Unfortunately, most of his contacts are not picking up

and his GPS seemingly leads the cops to search the wrong areas. Desperate regarding

his fast-approaching wedding, Kawamura creates a Twitter (here somewhat

unfortunately renamed “Pecker”) handle for #Manholegirl, assuming a trapped

woman will better motivate strangers to collaboratively determine his location.

Of

course, he must give them accurate details, so he pretends “#Manholegirl” is

his sister, a potential victim of those he wronged through his philandering.

Ominously, the net weirdos focus on his jealous colleague, Etsuro Kase, as

their prime suspect.

Michitaka

Okada’s screenplay takes some dark turns, while depicting the lunacy of online

mobs. Awkwardly, the cops do not inspire much confidence either. Consequently, Kawamura

might just be on his own—and the run-off water from a nearby abandoned industrial

building steadily rises.

Her hair is black as coal, but her skin and robes are ghostly white. Any

half-witted genre fan can immediately tell she must be some kind of

supernatural entity. In this case, she is a Yuki-onna, often referred to as a

snow witch. If that sounds familiar, maybe you read the Lafcadio Hearn short

story or saw it adapted as part of Masaki Obayashi’s truly classic anthology

film, Kwaidan. This Yuki-onna is that Yuki-onna. Three years after Kwaidan,

Hearn’s snowy story was translated into a full-length feature., but Tokuzo

Tanaka’s The Snow Woman remains true to its source and chillily

atmospheric, as viewers will see when a new 4K restoration premieres this

Friday on OVID.TV.

Instead

of wood-cutters, this time around, a master wood-carver and his apprentice

traveled deep into the snowy woods in search of the perfect tree for the elder

artist’s final masterwork. Late that night, the long-haired Yokai glides into

the cabin where they took refuge, freezing the old man to death with her frosty

projections (sort of like Marvel’s Iceman). However, she spares Yosaku’s life, because

he is young and just too darned good-looking. She insists on one condition—he must

never, ever speak of what happened. Should he break his word, she will quickly finish

the job.

Several

days later, while Yosaku still grieves and recuperates with his master’s widow,

a strange woman takes shelter from the rain in their modest home. Obviously,

viewers can tell the eerily beautiful Yuki is the Yuki-onna, but Yosaku never

makes the connection. Instead, he falls in love with her as they both comfort

the ailing widow. Unfortunately, his soon-to-be wife also turns the head of the

cruel local lord.

Among anime fans, Mobile Suit Gundam is considered the granddaddy of the mecha

genre. Yet, during its initial series run, budget shortfalls constantly forced

producers to cut corners. Series director Yoshiyuki Tomino believed the

economizing was particularly conspicuous throughout the fifteenth episode, so

he withheld it from most subsequent distribution packages. However, he still

believed the story had potential. Years later, this interlude from the Earth

Federation’s battle against Zeon separatists gets a feature-length remake in Yoshikazu

Yasuhiko’s Mobile Suit Gundam: Cucuruz Doan’s Island, which releases

Tuesday on BluRay.

All

you really need to know about the Battle of Jaburo is recent momentum has

favored the Federation, but Zeon has a major game-changing counter-offensive

planned. According to his orders, Captain Bright Noa dispatched Amuro Ray and

his comrades Kai Shiden and Hayato Kobayashi on a “mopping up” operation,

targeted suspected sleeper operatives on Alegranza, perilously near their

Canary Islands base.

Unfortunately,

after the disoriented Ray separates from his unit, he is ambushed by a vintage

Zaku, a Zeon mecha suit. Per protocol, Shiden and Kobayashi must leave him

behind. However, he will not face the sort of peril they fear. Instead, Cucuruz

Doan, the pilot of the Zaku, helps nurse Ray back to help and offers him hospitality

in his farm, a refuge for two dozen or so war orphans.

While

Ray is eager to rejoin the war, Doan has declared his own separate peace. He

bears Ray no ill-will, but he will not do anything that could bring warfighting

back to his island. Consequently, Ray wastes days searching for the Gundam Doan

hid alongside his Zaku. Yet, as Ray comes to know the orphans, he better

appreciates Doan’s desire to protect them and his aversion to the ongoing war.

Of

course, war inevitably returns to Alegranza, whether Doan likes it or not. Having

lost contact with their sleeper operative, Doan, the sinister Zeon commander M’quve

deploys a unit of Zakus to take charge of the doomsday weapon buried in the

island’s subterranean caverns. Ray’s friends are also on their way, since

Captain Noa conveniently feigned engine trouble, to facilitate the unsanctioned

rescue operation he knew they would launch.

The

contrasting ways Ray and Doan relate to war gives this film some intriguing

philosophical heft. It is easy to see why Tomino considered the original

episode lost a lost opportunity. The storyline is also easy to carve out of the

overall series narrative. However, much of the business involving the orphans

is a way too precious.

The disingenuous act like the tiktok divestment bill is an attack on the

Interstate Highway system, but apps come and go all the time. When did you last

check your Myspace page? In this film, the Mimi app is already past its prime,

but one of its most viral users still pulls a frustrated office drone into the

mystery of her life in Takamasa Oe’s Whale Bones, which screens today

during this year’s Japan Cuts.

Poor

tragically-average Mamiya is blindsided when his fiancée dumps him, so he goes

on a traditional hook-up app, where he meets the woman whom he will know as

Aska. This film really is not about that app. Instead, it is all about who Aska

is, or was. Even though he quite likes her, their date takes a surprisingly

dark turn, leaving him wondering about her.

Aska

explained her status as one of the top users of Mimi, which is sort of like

tiktok, except each video is geo-synched to a particular location. To see the

video, you must be at the spot where it was “buried.” To sleuth out the truth

of Aska, Miyami must discover all the videos she buried. Some are well known by

her followers, who still revisit them often, but others remain largely secret.

In

some ways, Whale Bones (a terrible, misleading title for an otherwise

very smart film) feels more speculative than it probably is. Quite strikingly, Oe

stages each buried video as if Aska is in the room talking to Miyami, like a

full-size hologram, even though she is really just a video on his smart phone. As

a dramatic technique, it is brilliantly effective—sometimes devastatingly so.

It also would make an amazing double feature with Morel’s Invention,

which would be spoilery to that Italian film to explain.

It's a classic question: “who was that boxed man?” It turns out, it is considered

bad form to ask, at least according to this Box Man. Although there is not a

similar racial component, Kobo Abe’s character shares the nihilistic

existentialism of Ellison’s Invisible Man. He also has a bit of Holden

Caulfield and Oscar the Grouch in him. He might be an anonymous drifter, but

people are weirdly fascinated with him in Gakuryu Ishii’s The Box Man, based

on the Kobo Abe novel, which screens today as part of this year’s Japan Cuts.

According

to the man who only calls himself “Myself,” you can see the reality of society

from a box. He knows we’re all a bunch of phonies. Yet, he claims: “those who

obsess over the Box Man, become the Box Man,” and he should know, because he is

the Box Man.

The

nefarious “General” and his accomplice, the “Fake Doctor,” are the latest to get

fixated on his peculiar vagrancy. His box is a bit like Snoopy’s dog house. He

managed to stash a lot of stuff in there, but like a Scot’s kilt you don’t want

to look underneath his box. The General’s interest stems from a murky criminal

plot, wherein he will assume the Box Man’s identity to evade justice. However, Box

Man’s eccentric lifestyle appears to slowly seduce the Fake Doctor.

Meanwhile,

the Box Man might be feeling something remotely human for Yoko, the Fake Doctor’s

fake nurse. Apparently, her checkered past gives the Fake Doctor the leverage

to force her to do his bidding. Of course, her shame only creates a stronger

sense of kinship with the Box Man.

Before

his death, Abe gave Ishii his blessing to adapt The Box Man, which means

this film has been twenty-seven years in the making. It is easy to understand

why it was long considered unadaptable. Clearly, Abe was addressing issues of

identity and epistemology in a very postmodern fashion. However, Ishii manages

to bring it to the screen in a way that still gives us something to watch, which

is appreciated. In fact, it often has the flavor of an obscure Borgesian caper.

Obviously,

The Box Man is not for everyone. If you are unsure, consider it a “no.”

As a point of reference, it is somewhat more grounded than the films of

Robbe-Grillet, but also less stylish. Ishii’s adaptation is deeply grounded in existential

and post-structuralist philosophy, but Michiaki Katsumoto’s jazzy score is a

blessing that greatly aids the film’s watchability. However, the deliberately

elusive payoff is intentionally frustrating.

In one way, the timing is good for a busker like Luca (a.k.a. Kyrie),

because she might find fame on privacy-invading, spyware-infecting,

propaganda-spewing tiktok. However, the timing of the 2011 earthquake and

tsunami during her childhood was absolutely tragic. The resulting trauma

clearly persists in director-screenwriter Shunji Iwai’s Kyrie, which

screens during the year’s Japan Cuts: Festival of New Japanese Film.

When

Maori first met Luca, the orphaned girl could not speak, but she could sing.

That is still true when she encounters a decade or so later, performing on the

street, but they now call themselves Ikko and Kyrie. The former Luca has talent

and Ikko still feels protective urges towards her, so she volunteers to manage

Kyrie’s career.

Kyrie

needs some help and Ikko’s intentions are honest, but there is something dodgy

about her new manager. Not so surprisingly, Kyrie is too naïve to see that. For

a while, Ikko’s street smarts serve them both well, but she clearly appears to

be running from a mysterious man.

Frankly,

Kyrie/Luca’s backstory is not so difficult to anticipate, but Iwai still takes

great pains to tease it out across the film’s somewhat excessive three-hour

running time. Yet, it should be fully stipulated when the film finally revisits

the fateful day of March 11th, it is agonizingly tense. Many viewers

will be holding their breath, like they never have in any horror movie, even

though they know what is coming.

Iwai

can make viewers passionately love him and viscerally hate him, all in the same

film. Kyrie is a perfect example. There is suffering and there is catharsis,

but in this case, the synthesis of the two is somewhat off. The tunes are also

integral to the story, but only Kyrie’s closing song really lands, either melodically

or emotionally.

The 1980s were an unusually good time to be a jazz musician in America.

Wynton Marsalis made acoustic bop commercially successful again and the

venerable Blue Note Records was re-launched. Evidently, in Japan, the jazz

scene more resembled 1930s Chicago. Most musicians played in Ginza clubs that

were clearly controlled by the Yakuza, at least according to musician Hiroshi

Minami. He survived to write about those times in his memoir, but

director-co-screenwriter Masanori Tominaga splits his persona in half in the

appropriately syncopated and stylized adaptation, Between the White Key and

the Black Key, which screens as the opening night film of the 2024 Japan Cuts.

Hiroshi

yearns to play jazz, but his hip teacher knows he needs some seasoning, so he recommends

gigging in the seedy Ginza cabarets. Sure enough, Hiroshi quickly gets an

education. Fatefully, a mysterious Yakuza freshly released from prison requests

Rota’s “Love Theme from The Godfather.” Hiroshi obliges, even though the

leader on the gig freaks out six ways from Sunday.

It

turns out only Kumano, the boss known as “the King of Ginza” can call that tune

and only Minami (Hiroshi’s future self, who coexists in the same time-frame)

can play it. Fortunately, Hiroshi’s gig was at a club where musicians

traditionally wear masks, because news of the transgression spreads quickly.

As

it happens, the artistically frustrated Minami intends to desert Ginza to study

real jazz at the Berklee School of Music. He only confides his plan to Chikako,

who agrees to aid his getaway. That means they will need a sub to cover for

him, so she recruits Hiroshi, an old friend from school.

Even

though Tominaga and co-screenwriter Tomoyuki Takahashi have that Lynchian

looping time thing going on, it is not what defines the film. Questions of

artistic integrity and compromise are more important (and timeless) themes.

Having played in Al Capone’s clubs, Armstrong would well understand Minami’s relationship

with Kumano.

Even

though little is done to physically distinguish Hiroshi from Minami, Sosuke

Ikematsu is so good at creating such ying-and-yang personalities and carries

himself so differently, viewers might start to wonder if he is the same thesp

(which indeed is the case). Go Morita is also a wild chaos agent as the

mysterious Yakuza. Whenever he shows up, the audience knows there will be

trouble.