Death never comes for a holiday at Tenmasou Inn, but she brings plenty of

guests. She has a relationship with the two Tenma Sisters and their mother to

host spirits in limbo, as they decide whether to keep living or to proceed unto

death. The latest guest she escorts will be quite a surprise: a half-sister the

Tenma siblings never knew they had. Its is also news to the traumatized Tamae

Ogawa, who will have a lot to process in Ryuhei Kitamura’s The Three Sisters

of Tenmasou Inn, which screens today as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Nozomi,

Kanae, and their irascible mother Keiko Tenma are dead, but Ogawa is not, at

least not yet. Her young life has been hard, because her father abandoned her

at a young age, just as he did with Nozomi and Kanae. They still had Keiko, but

Ogawa’s mother tragically died during her infancy. Despite her unfortunate current

circumstances, Ogawa is delighted to meet new family, as are her half-sisters.

However, the boozy Keiko is less than welcoming.

Considering

herself part of the family, Ogawa insists on working at the inn. Since most of

the day-to-day responsibilities fall on the older, more professional Nozomi,

she appreciates Ogawa’s help. She is especially grateful when her half-dead half-sister

takes the hospitality lead with two difficult guests. One is an old lady who

takes pleasure in nitpicking. The other is Yuna Ashizawa, a privileged influencer,

who attempted suicide. Both are somewhat disarmed by Ogawa’s honesty and lack

of guile. Nevertheless, Ashizawa cannot control her disruptive behavior. Apparently,

even in near-death, some Millennials remain obnoxious and entitled.

Tenmasouu

Inn is

a lovely looking film that seems worlds removed from Kitamura’s recent horror and

action movies, such as Downrange and The Doorman. However, he

previously helmed a much darker thriller set within the “Sky High” manga

universe that Tenmasou Inn is also adapted from.

It

turns out he can jerk tears with the best of them. Thematically, Tenmasou

Inn is a lot like Kore-eda’s classic After Life and Edson Oda’s Nine Days, but it is more sentimental, yet also sometimes more surprising. It is

all achingly sentimental, but its Japanese-ness makes it really appealing, sort

of in the tradition of Departures.

If you were stuck in a time loop while at work, but you never noticed, your

job probably kind of sucks. That is pretty much where Shukai Yoshikawa and her

office mates are. To break the loop, they will have to work together, but that

is always harder than it sounds in office-place comedies, very definitely including

Ryo Takebayashi’s Mondays [See You ‘This’ Week], which screens tomorrow

as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Yoshikawa

was hoping to jump ship to the bigger, more prestigious advertising company

that often subcontracts Nagashige’s rag-tag firm, but that will never happen

while she is stuck in a loop. Two of her junior coordinators managed to awaken

her consciousness to the time loop and they have developed some theories as to

what their next course of action should be—because they have had time think on the

problem and watch a few movies.

They

need her to awaken her direct superior, so he can awaken his, and so on,

working their way up to Nagashige. If they go straight to the boss, he will not

take them seriously. This might be an outlandish situation, but this

chain-of-command mentality definitely strikes a chord, doesn’t it? They also

have a theory as to how the manga-loving Nagashige can break the curse that has

befallen all of them, but he will take some serious convincing.

Apparently,

the Japan film industry has a massive competitive advantage when it comes to

producing original time loop movies. Just like Junta Yamaguchi’s The Infinite Two Minutes, Mondays takes a somewhat familiar premise and turns

it inside out. In this case, Takebayashi and co-screenwriter Saeri Natsuo also

add sly workplace humor just as funny or funnier than any episode of The

Office (either of them).

Freud would be pretty impressed by Hana Shimon. The interpretation of her

dreams could save the world from apocalyptic destruction. Of course, she is not

really dreaming. She is traveling into the “Sea of Sentiment,” a realm that is

as real as our own—and what happens there directly impacts our own world. It is

not looking good for us. There are only two weeks until Armageddon, unless

Shimon can save us, assuming we even deserve it in Kazuaki Kiriya’s From the

End of the World, which screens tomorrow as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

We

need Shimon to save us, but she has it hard. Her parents died when she was

seven and the grandmother who served as her guardian recently passed. She waits

tables for money to live on. When she makes it to school, she is relentlessly bullied

by the worst mean girl. Then Shogo Ezaki and Reiko Saiki show up from the

National Police asking if she dreams much. She certainly will that night.

Suddenly,

she finds herself transported to a black-and-white universe very much like feudal

Japan, where she befriends Yuki, a soon-to-be orphan, thanks to the marauding ronin.

When she tells Ezaki and Saiki about it, they immediately launch a pre-set contingency

plan, which spares Japan great damage from a surprise earthquake.

It

turns out there is a Millennium-like group in the National Police that

understands how that dream world affects our universe and they have persuaded

the Prime Minister to act on their warnings. Unfortunately, there is an ominous

dream-walker sort of figure who can operate in both worlds—and he knows about

Shimon. However, the greater danger to her might be greater from those who want

to topple the current government, by exposing the PM’s dependence on a “fortune

teller.”

End

of the World is

definitely a return to big idea, big spectacle genre films for Kiriya, after

the English language production Last Knights, which was a lot of fun,

but was not nearly as ambitious or significant. In contrast, this is a

distinctly original conception of the end times. It incorporates some really

crazy extremes that are too complex and too spoilery to get into here. It is

safe to say this is a big film that is sure to inspire a lot of analysis over

time.

During WWII, Japan’s invasion of Mongolia did not go very well for them. That

is why they agreed to a neutrality treaty with Stalin. Yet, after the fall of

Communism, the two nations forged strong diplomatic ties. That is a lot of

history. The history is particularly complicated for Saburo, an aging

industrialist, who served in Mongolia during the War. He has a daughter somewhere

on the steppe, whom he hopes his wastrel grandson can find before he dies in

Kentaro’s Under the Turquoise Sky, which screens as the centerpiece

selection of the 2023 Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Saburo

is dying, but he knows the hard-partying Takeshi is not sufficiently

responsible to succeed him yet. He hopes his mission to Mongolia might season

him a little. Of course, he cannot send him alone. His unlikely companion will

be Amaraa, a Mongolian national who was arrested for stealing one of Saburo’s

horses (and giving the cops an extremely cinematic chase on horseback).

Fortunately, the old man is a good judge of character, so he hopes the horse

thief can help the clueless Takeshi find the woman known as “Japanese Tsermaa.”

In

terms of storyline, Turquoise Sky is not excessively complicated. It

really is your basic road narrative with lessons to be learned by a young man—when

he least expects them, of course, but the sweeping Mongolian scenery is an

amazing visual (they do not even make to the massive Genghis Khan Statue

Complex). Kentaro (an actor turned director, probably best known for roles in Rush

Hour 3 and Kiss of the Dragon) also achieves a potently wistful

vibe. Arguably, there is strength in the simplicity of his approach.

Amarsaikhan

Baljinnyam (who also co-wrote the screenplay) is also quite remarkable as the

taciturn but strangely charismatic Amaraa. His relationship with Takeshi is

smartly written and subtly played. They do eventually reach friendly terms, but

there is never any blubbering bro-mance. They just start to accept each other.

Convenience stores (konbini) are important in Japan. They are places to buy

cup-noodles and iced coffee in a can (so good). Kato is about to walk into one

that might look modest, but it is actually quite mysterious. The cooler door

ushers him through to a Lynchian world in Satoshi Miki’s Convenience Story,

which screens tomorrow as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Kato’s

screenwriting career is on the skids, because his bro comedies are out of step

with woke producers. Ironically, his resentful live-in girlfriend Zigzag’s

career might be on the verge of taking off, while he falters. After

ill-advisedly blowing off steam (by abandoning her dog in the middle of

nowhere), Kato finds himself broken-down outside an empty konbini. Frankly, he doesn’t

even realize it when he gets pulled through the cooler door-portal, but he

certainly notices Keiko on the other side.

In

this world, she manages the convenience store with her schlubby husband Nagumo.

Since he is stranded, they hospitably offer to put him up. They are almost

suspiciously welcoming. However, a David Lynch-worthy Postman Always Rings

Twice-esque melodrama develops, when Nagumo leaves Kato and Keiko alone for

hours, while he practices his air-conducting in the forest.

Convenience

Story is

not entirely successful, but it is more watchable than overly self-serious

Lynchian secret world movies like Silent River or Chariot,

because Miki maintains a brisker tempo. Viewers never share the feeling they

are also stuck in an isolated konbini. Miki’s adaptation of the novella written

by Japan Times film critic Mark Schilling also retains an ironic sense

of humor.

Winny was sort of like a Japanese Napster, but it was originally envisioned

for more Wikileaks-style purposes. At least that was the defense offered by the

creator’s lawyers when he was put on trial for facilitating copyright

infringement. Technically, Isamu Kaneko is on-trial, but so is his creation in

Yusaku Matsumoto’s Winny, which screens as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Kaneko

fits every programmer stereotype, making him a difficult defendant for the old

school judges to relate to, or understand. Fortunately, Toshimitsu Dan gets him

enough to formulate his defense, while also communicating persuasively. Dan

also has the benefit of Akita Masashi, his firm’s crafty senior partner, who is

serving as co-counsel.

Of

course, the naïve Kaneko makes things much more difficult for them, by signing

pre-written statements the Kyoto police assure him they he can change later. The

case is strange in many ways, since it focuses on Kaneko instead of those who

actually pirated copyrighted works. However, it is not lost on anyone that the

same police precinct is concurrently denying corruption charges prompted by

financial records distributed anonymously via Winny.

During

the trial, the word “proliferate” takes on great significance. In fact, these

court room scenes and all the trial prep are really crisply executed. Unfortunately,

Matsumoto and co-screenwriter Kentro Kishi never fully integrates the police

slush fund subplot with the rest of the film. It is a shame, because Yoshioka

Hidetaka is excellent portraying Senba, the police whistleblower.

Even though they had Godzilla and Gatchaman, Star Wars still blew the

minds of Japanese science fiction fans when it opened in 1978 (in Japan). That

is especially true for Hiroshi. He aspires to remake Star Wars for his

high school arts festival, but the project evolves into something more original

and more personal in Kazuya Konaka’s Single8, which screens today as

part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Hiroshi’s

first film was a Jaws “homage” called Claws that technically

pre-dated Grizzly, but he still finds it embarrassingly amateurish by

his current standards. He has been obsessively trying to recreate the opening Imperial

Destroyer scene in Star Wars—notice how nobody calls it “A New Hope” in

1978—with the help of his pal Yoshio. Since nobody has a better idea, they pitch

their remake to their class, for the school’s arts festival. Their teacher, Mr.

Maruyama, is reasonably receptive, but he encourages them to create their own

story, with a message that will speak to their classmates.

With

input from Sasaki, another fannish classmate, they brainstorm the plot of Time

Reverse, in which aliens alarmed by Earthlings’ destructive tendencies make

time run backwards, so humanity can fix its mistakes. The only two people

unaffected are a teen couple, whose relationship is on the rocks. For Hiroshi,

the greatest advantage of their new story is that his longtime crush Natsumi

might be interested in playing the female lead.

Although

Hiroshi and his friends are initially motivated by their Star Wars love,

Single8 (Japan’s equivalent to Super8) has far fewer references than

Patrick Read Johnson’s 5-25-77. It is also considerably livelier and

much less whiny. Frankly, a better comparison film would be the original One Cut of the Dead, because both films are such affectionate tributes to the filmmaking

process.

Oda Nobunaga's wife Nohime did not think much of him at first, but she

became his Lady Macbeth, driving his ambitions, before settling into an Eleanor

Roosevelt role as a trusted advisor. At least that is how a new film commissioned

to celebrate the Toei film studio’s 70th anniversary presents her.

The mysterious Nohime finally gets equal screentime with her legendary husband

in Keishi Otomo’s The Legend & Butterfly, which screens tomorrow as

part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Nobunaga

and Nohime only married to make peace between their clans. The courtship was

rocky, to say the least. Nohime only agreed, because she intended to kill him, just

like her previous husbands. However, she must accept his protection when her

clan is attacked. Of course, Nohime wants revenge, but she pushes Nobunaga to

take more when he emerges as one of the most powerful Daimyo in Japan.

For

a while, L&B is like a Chanbara Mr. & Mrs. Smith, because

they are both serious butt-kickers, especially her. However, as the film takes

on epic scale, Nobunaga becomes the more prominent force. Yet, their

relationship also continues to evolve, and in some ways, deepen.

Considering

how little was documented on Nohime’s life, beyond her status as Nobunaga’s

wife, screenwriter Ryota Kosawa’s speculative attempts to fill-in the blanks

are quite convincing. He creates a compelling character, whom Haruka Ayase

brings to life quite vividly. By far, she is the most compelling figure in the

film. Kosawa and Otomo definitely present her from a modern, pseudo-feminist

perspective, but Ayase makes her credible as a woman of her era and relatable to

contemporary viewers. She also looks impressive during her several action

sequences.

Kenji Miyazawa was poorly served by his publishers in his lifetime, but anime

and manga adaptations made him a posthumous giant of Japanese literature. His

life was tragically short, but his father believed in his talent, at least most

of the time. The Miyazawas’ close but sometimes difficult father-and-son relationship

is the focus of Izuru Narushima’s Father of the Milky Way Railroad,

which screens tomorrow as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Masujiro

Miyazawa is a reasonably prosperous country pawnbroker, like his grouchier

father. He considers himself a contemporary man of the late Meiji Era, but Masujiro

still assumes his firstborn son will succeed him in the family business.

However, as Kenji grows older and more headstrong, he envisions other destinies

for himself, including as an agricultural expert and as acolyte in a severe

Buddhist sect.

Of

course, writing was his true calling, but it takes a family tragedy to

re-awaken his fantastical creativity. Throughout it all, Miyazawa’s father

continues to support him, despite often losing patience in his flaky behavior.

In

fact, their relationship is surprisingly believable. There is a lot of

tear-jerking in Narushima’s film, but he and the cast earn their big emotional

pay-offs. Sadly, this is the kind of deeply felt family drama the American film

industry cannot be bothered with anymore. There is no secret abuse to expose or

power dynamics to subvert. It is just a family, relatively progressive for its

time, dealing with the challenges and disappointments of life.

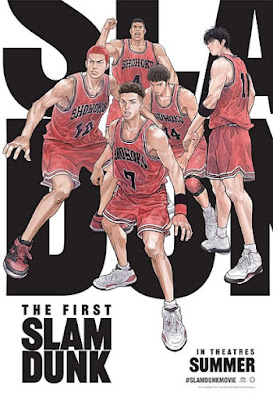

Do you miss the joy of basketball, before the NBA became consumed with the

pursuit of money from China? Ryota Miyagi and his teammates do not necessarily

like each other, but they play with a pure love for the game. Despite their talent,

nobody gives Okinawan students much of a chance against the defending Japanese

high school champions, not even their fans, in Takehiko Inoue’s The First Slam

Dunk, an animated adaptation of his manga, which screens as the opening

night film of the 2023 Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

As

we see in flashbacks, Miyagi idolized his older brother Sota, who was one of

the top basketball prospects in Japan. Tragically, Sota was lost in a boating

accident, devastating Ryota. As a tribute to his older brother, Miyagi

obsessively pursues his hoop dreams, even though his single mother has her reservations

regarding the emotional toll.

Throughout

their game against Sannoh, Miyagi keeps flashing back to memories of his

brother. He also revisits some of his first encounters with his Shohoku teammates,

like their outside shooter, who was once a bully, but Miyagi won him over, by

taking his worst beating like a man.

Miyagi

is quick, but undersized, so he struggles against Sannoh’s press. Their big man

also gets into the head of Shohoku’s center. However, Miyagi’s Zen-like coach

has faith and a knack for making the right moves.