Monsters are like bad movies. Nobody intentionally sets out to make either one, but they happen anyway. In

this case, Vicaria’s intentions are good. She wants to resurrect her older

brother Chris, who was killed far too young. Of course, playing God always

turns out to be an act of dangerous hubris in films, as is indeed the case in

Bomani J. Story’s The Angry Black Girl and Her Monster, which opens

today in theaters.

According

to Vicaria, she isn’t just trying to bring Chris back to life. Her true

spiration is to cure death. If she could cure taxes too, that would be great. Obviously,

she is aware of Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, because she labeled her lab journal

“The Modern Prometheus.” Story also has seen a few Frankenstein films in his

time, judging from the crackling electricity that powers her experiments and a pivotal

line of third act dialogue that transparently echoes Bride of Frankenstein.

Heck, maybe Vicaria’s surname is even Frankenstein. It is coyly never revealed,

but we know it is unusual and sounds “German.”

Like

every Frankenstein Monster, the re-animated Chris turns out to be far more

violent and far less rational than Vicaria hoped. At least he has plenty of

potential victims in their economically depressed neighborhood. There are the

cops everybody hates and Kango’s drug gang, who prey on their human frailties.

Sadly, Vicaria’s father has been one of their regular customers, since her

mother was killed by a stray bullet.

In

terms of style and tone, Angry is somewhat akin Michael O’Shea’s The Transfiguration. Without question, Story emphasizes the socio-economic

circumstances of the characters, but it is not as didactic as you might fear.

True, Vicaria’s best friend Aisha is all-in for woke Columbus rants, but they

sound as counter-productive as Vicaria’s experiments turn out to be.

If ever there was an animal in need of a hero, it would be the pangolin.

Thanks to the black market in Mainland China (where their meat is considered a

delicacy and their scales are a staple of “Chinese medicine”), the scaly mammal

remains one of the world’s most endangered animals. These pangolins residing in

a subterranean Fraggle Rock-like fantasy world face an even graver

peril. However, young Peter Drawmer just might be the hero their prophecies

foretold in screenwriter-director Matt Drummond’s The Secret Kingdom,

which opens tomorrow in New York.

According

to the prologue fairy tale, the two worlds were once connected, but when the

young, brilliant king died, they were split apart. Drawmer always lived in our

world above, but when his family moved to his father’s drafty old ancestral

home in the countryside, the fantasy world below starts calling him. Then, that

night, a hole opens in his room, swallowing his bratty little sister Verity, so

he reluctantly dives in after her.

Down

below, the Pangolin oracle immediately hails Drawmer as the foretold king, but

the Pangolin general is skeptical. Regardless, if Drawmer is their savior, he

hasn’t come a minute too soon. The Pangolin soon find themselves under attack

from the forces of darkness. Peter and Verity get cut off from the rest of the

Pangolins, but they still have Pling, who is well-versed in the prophesies, as

well as epic songs that serve as the pangolins’ maps for navigating their

fantasy world.

The

pangolins and many of the other fantastical creatures are surprisingly

well-crafted. Secret Kingdom might be ripping off the Henson workshop’s

greatest hits, but it does so surprisingly well. The fantasy quest, involving

pieces of a puzzle Drawmer must assemble to restore the fantasy world’s

internal clock, is serviceable enough. The problem is both Drawmer siblings are

way too young (and way too passive) for a fantasy so transparently inspired by The

Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. They just aren’t right for the film.

Salvador Dali was a self-described “anarchist, monarchist Catholic.” That is

three strikes against him in today’s groupthinking world, but Mary Harron made

a film about him anyway. He was, after all, the most recognizable artist of his

time, or any other. Dali knew it too. His fame combined with his eccentricity

and constant financial shortfalls makes him decidedly difficult to work with in

Harron’s Daliland, which opens Friday in New York.

At

this late stage of Dali’s career, he can practically sell anything with his

signature on it, which is fortunate, because he and his wife Gala spend money

like water. Frankly, he and his manager, Captain Moore, might even be complicit

in flooding the market with dubious prints and lithographs. However,

fresh-faced (and fictional) James Linton has yet to be so disillusioned by the

art world (but it will come). Initially, he is thrilled when his gallerist boss

“lends” him to Dali to assist the preparations for his upcoming show, which

still includes painting eighty percent of it, or so.

Initially,

Gala Dali was also hoping Linton would “assist” her too, but he wriggles out of

those duties when she starts obsessively focusing on her latest “project,” Jeff

Fenholt, the Broadway star of Jesus Christ Superstar, who would

eventually become a musical televangelist. Ironically, Dali’s bemused pal Alice

Cooper, who eventually starred in the live TV production of Superstar, also

appears as a minor supporting character, reacting with a healthy degree of

skepticism to the artist’s more over-the-top provocations. Of course, Linton

thinks it is all quite charming, especially Ginesta, Dali’s waifish

model-entourage member, until things really get to be too much.

In

addition to the three strikes from Dali’s politics, Daliland carries a fourth

strike thanks to Ezra Miller, who appears in flashbacks as the young Dali. Yet,

ironically, the “troubled” thesp is arguably more convincing and compelling as

the younger Dali, especially when recreating the artist’s fits of spasms and

bouts of neuroses.

Admittedly,

Sir Ben Kingsley is highly entertaining to watch chewing the scenery as the

older incarnation of the artist-provocateur, but his performance is more about

embracing and accentuating Dali’s eccentricities than exploring his inner

psyche. Arguably, Miller is more successful at the latter, with far less

screen-time.

These superheroes are inspired by the Bronze Masks of Sanxingdui unearthed by archaeologists

in Sichuan back in the late 80’s, but they have been upgraded to gold. Apparently,

gold is more blingy and it presumably costs the same to animate. Charlie would

also prefer gold, because of its higher re-sale value. Few people consider him

a hero, least of all Charlie, but a hero-less mask chooses him anyway in Sean

Patrick O’Reilly’s Heroes of the Golden Mask, which releases this Friday

in VOD.

Li’s

father was the leader of the Golden Mask quintet of heroes, until he died in

battle against the evil super-villain Kunyi, who is determined to steal

Sanxingdui’s mystical Jade Blade. The archer and her team-mates, including a Chinese Zodiac-shape-shifter, a hammer-wielding fish-person from Atlantis, and a telekinetic

juggler, know Kunyi will be back, so Li must let her dad’s mask divine its next

host. Bizarrely, it picks crime-infested contemporary Chicago as the place to find

a new hero.

Charlie

is an orphaned pick-pocket, who lives by his fingers and wits. He is a thief,

but he is hardly the nastiest criminal in Chicago. Unfortunately, he owes money

to the far worse Rizzo, whose voice was supplied by the late Christopher Plummer.

When things get too hot for Charlie, Li provides a convenient escape, but he is

reluctant to embrace his new heroic role.

Golden

Mask holds

the distinction of being Plummer’s final screen credit. Frankly, his familiar

Transatlantic accent would seem like an odd choice for the Capone-like Rizzo, but

his growling whisper does not sound completely out of place. Without a doubt,

Ron Perlman’s voice is best cast as the sinister Kunyi, whereas Patton Oswalt

is the most annoying as Aesop, the whining Atlantean.

Asian detectives like Charlie Chan. Mr. Moto, and James Lee Wong were popular

in the 1930s, but they have become controversial in retrospect, because they

were portrayed by European actors (except Mr. Wong, played by Boris Karloff,

who was of Indian heritage). Edison Hark is a Honolulu cop like Chan, but he is

definitely cut from a different cloth, reflecting more contemporary

sensibilities. His latest investigation takes him to San Francisco, but it hits

really close to home for Hark in Pornsak Pichetshote’s graphic novel the

Good Asian, with art by Alexandre Tefenkgi and Lee Loughridge, which

releases today in a deluxe hardcover bind-up.

Hark

did not really want to come to San Francisco, but his wealthy white adopted father Mason

Carroway has fallen ill and may never recover. As a desperate final gesture,

Hark’s adoptive brother Frankie requested his help finding their father’s possible

lost love, Ivy Chen. She had a rather complicated history with the Carroway

family. In addition to her ambiguous relationship with their father, Frankie

might have also carried a torch for her too, but not Hark. He had a thing for

Frankie’s sister, Victoria. She was usually away at boarding schools and rarely

at home during their youth, so it wasn’t so weird—at least that is what they

told themselves.

Hark

deliberately references Chang Apana, the Honolulu cop who was the real-life

inspiration for Charlie Chan. However, the hardboiled family dynamics have more

of a Big Sleep vibe, with the search for Ivy Chen replacing that for

Sean Regan. Yet, the attitude towards just about all forms of American

authority in 1936 is more in keeping with Polanski’s Chinatown, but with

a far greater understanding of the real Chinatown.

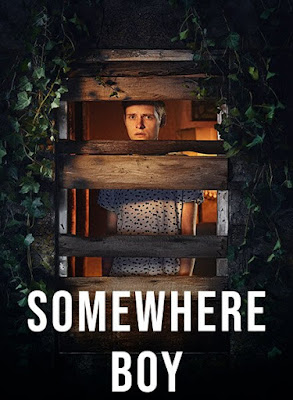

Yes, Danny's father made a lot of mistakes, but at least he introduced his

son to a lot of great classic films and music. Nothing too explicit, of course.

To say Steve was an over-protective parent would be an understatement. Sadly, the

reasons for his behavior are understandable, but that does not make them any

less detrimental to Danny’s psychological development in writer-creator Pete

(not Peter the Hobbit guy) Jackson’s eight-part Somewhere Boy, which

premieres Wednesday on Hulu.

When

he was still infant, Danny’s mother was killed in a hit-and-run accident. The negligent

driver also killed a good part of Steve at the same time. Breaking ties with

his sister Sue, Steve raised Danny in an isolated country cottage, brainwashing

him to believe only dangerous monsters lived outside their house, since they

were mostly likely the last people on Earth left alive.

Steve

was definitely moody, but he tried be a loving father. Danny idolized him,

believing he kept them alive through his hunting and foraging. He also

enthusiastically adopted Steve’s tastes in films and music (including Hoagy

Carmichael). Naturally, his father’s suicide hit Danny hard. Fortunately, Steve

left word with Sue to come looking for Danny before he died.

Danny

breaks Sue’s heart, for multiple reasons, but it is hard to communicate with

the stunted and withdrawn teen. Her own teenaged son Aaron can hardly relate to

Danny and he resents having to share his room with his weird new cousin. The

more Danny hears about his dad, the more awkward Sue and Aaron feel around him,

but at least he develops a goal. He is determined to find the “monster” who

killed his mother and make him pay.

Although

there is some menace surrounding Danny’s hunt for the hit-and-run driver, Somewhere

Boy is even less of a thriller than Sean Penn’s vengeance-seeking character-study

The Crossing Guard. Jackson is much more concerned with Danny and his

prospects for meaningful healing. There is a lot of forgiveness in the series,

both for Steve and Sue’s family, who struggle with Danny. It is easy to see

why. Unfortunately, the scenes involving the guilty driver are a bit

anti-climactic and frankly disappointing. Yet, the honesty of the extremely

dysfunctional family drama largely outweighs such missteps.

Lewis

Gribben is terrific as the twitchy, anti-social Danny, precisely because his

performance is so tightly restrained and inwardly focused. Samuel Bottomley is

also quite remarkable portraying the sullen Aaron, who starts to come out of

his own emotional shell as he comes to understand how much damage life has done

to Danny.

You can say GDR socialism was unifying, because it brought together the

Catholic Church and punk rockers—against the oppressive Communist regime. In

1989, Margarethe’s lover, Heinrich, regularly played with his band in a

dissident Church. Tragically, she could rarely attend, because she was confined

to an East German mental hospital, for punitive rather than medical reasons. German-born

French animator Lucas Malbrun revisits the final dark days of the GDR regime in

the short film Magarethe 89, which premiered at Cannes’ Quizane des

Cineastes 2023 (a.k.a. Directors Fortnight) and currently screens for free on

Festivalscope’s consumer-facing site.

Even

in the prison-like psychiatric hospital, there are inmate-patients willing to

inform on their fellow prisoners. However, Margarethe is determined to be free,

at least in her mind, but hopefully also in physical bodily terms too. At least

Heinrich is at liberty to play with his band, but he too must attend weekly “check-ups,”

if that is what they really are. Regardless, since it is 1989, viewers will

know the regime’s days are numbered, but for some, the act of informing is a

hard habit to break.

It is sort of like Groundhog Day all over again, but George Addo’s

new colleagues are doing it deliberately, at least until they get things right.

That is their job at the super-secret agency known as Lazarus. Whenever the

civilized world faces an extinction level event, they rewind time back to the

last July 1st, so they can fix things. That causes a lot of

confusion for Addo when he starts to remember what was rewound in creator-writer

Joe Barton’s The Lazarus Project, which premieres tomorrow night on TNT.

At

first, Addo was just a modestly hip British app developer on the brink of big-time

financial success. He married his girlfriend Sarah Leigh, but as they settled

down to live happily ever after, a virulent plague started killing everyone on

the planet. Then Addo woke up and it was July 1st, as if the last

six months never happened.

Of

course, Addo tries to warn the world of what is coming, but everyone assumes he

is crazy—except the mysterious Archie. She tells him where to meet her if he

remembers the next time it happens, which indeed it does. It turns out most

Lazarus agents need to be dosed with their memory drug before they can recall

past time resets. However, Addo is one of the few “mutants” that have developed

the talent on their own. His new moody colleague Shiv Reddy is another.

Fortunately,

Lazarus developed a sufficient vaccine for Covid-20, or whatever it was.

(Anyone who was suspicious about how quickly the last Covid vaccine was

developed—here’s your answer.) The bad news is a particularly massive nuclear

bomb nicknamed “Big Boy” has been stolen. The worse news is the apparent

involvement of Dennis Rebrov, a former Lazarus agent who turned against the

agency. He is now determined to see the world burn, which sounds inexplicably

nihilistic, but he has his reasons.

In

fact, many of the character-establishing flashbacks are among the best scenes

in Lazarus Project. Barton (whose screenwriting credits include Ritual

and Encounter) has a knack for character-driven sf. He largely punts

when it comes to credible scientific explanations, but so be it. He more than

compensates for a lack of Doctor Who-worthy doublespeak with his one-darned-thing-after-another

plot twists. Plus, he and the producers deserve credit for an additional,

complicating villain they reveal in episode seven. Here’s a hint: they are

committing genocide in Xinjiang.

Barton

and series directors Marco Kreuzpaintner (episodes one to four), Laura Scrivano

(five and six), and Akaash Meeda (seven and eight) keep viewers hooked, while

radically shifting our responses to Addo. He is clearly the protagonist, but

the demarcation between heroes and villains in Lazarus Project is a

subtle and shifting line.

Forget Fast & Furious and Mission Impossible. The most reliable

international action franchise is Don Lee’s “Beast Cop,” Ma Seok-do. He is more

rock than The Rock, more diesel than Vin Diesel, and at least ten times the

size of Tom Cruise. When his fists connect, people go flying. That happens a

lot in Lee Sang-yong’s The Roundup: No Way Out, which opens today in New

York.

The

criminals of Seoul have nightmares of Ma, but his fellow cops often tease the

good-natured giant. Joo Sung-cheol does not get to do that. Ma can tell his

colleague is dirty, but he cannot prove it yet. Ma’s team started investigated

the negligent murder of a woman who overdosed on “Hiper,” a new designer drug,

which led to a Japanese Yakuza-controlled drug ring. The operation is secretly

under Joo’s control and it has been skimming pills for extracurricular sales.

Having

figured out their books do not balance, the Yakuza has sent Ricky the enforcer

to teach Joo and his gang a lesson. It is a really bad time for Ma to start

sniffing around, especially when his supply of pills goes missing. However, he profoundly

underestimates the humble Ma. Their resulting cat-and-mouse game is a bit Columbo-like,

but physically, it is much rougher.

The

great joy of these films is watching Don Lee (a.k.a. Ma Dong-seok) punch,

pile-drive, and power-slap his way to the truth. Lee has a big, “happy warrior”

screen persona that is even more entertaining than Schwarzenegger in his 1980’s

prime. The Ma-Beast Cop films are perfect vehicles for his size and chops.

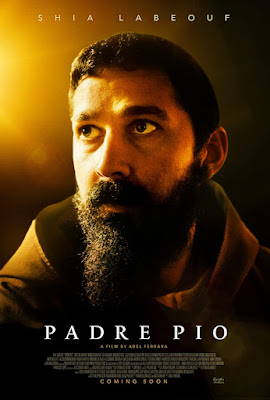

According to reports, Padre Pio (a.k.a. St. Pio of Pietrelcina) exhibited the

stigmata, healed the sick, bi-located, and faced multiple investigations from the

Vatican that were intended to discredit him. However, none of those things are

in this film, because why would they interest Abel Ferrara? Instead, viewers

will witness many of the future saint’s long dark nights of the soul. If you

thought he was tortured and tormented before, wait till you see him get the

Abel Ferrara-treatment in Padre Pio, which opens tomorrow in New York.

WWI

has ended and the men of San Giovanni Rotondo are making their triumphant

homecoming—but not all of them. This is the first example of how capricious and

unfair fate can be to the villagers. After the armistice, the land-owners

expect life to return to normal, but socialist rabble-rousers are organizing to

defeat the elite’s hand-picked candidate for mayor. Where is Padre Pio in all

this? Back at the monastery, wrestling with the Devil and his personal demons.

Is

that disconnection Ferrara’s whole point? Is this a statement on the Church’s divorce

from average people’s struggle to survive. That is certainly a valid

interpretation, but it feels somewhat at odds with the genuine (if somewhat eccentric)

Catholic spirituality of his best religiously themed film, Mary.

Even

by Ferrara’s raggedy standards, Padre Pio is a rather disjointed film.

There are moments of brilliant cinema, such as opening scene of the soldiers’ homecoming.

You can see Ferrara’s operatic fervor in all the secular passion play

sequences. However, whenever Padre Pio rages against the darkness, you half

expect Shia Labeouf to start baring his bottom, like Harvey Keitel in Bad

Lieutenant. Evidently, Ferrara was struck by the coincidence Padre Pio

started experiencing the stigmata around the time of the San Giovanni Rotondo

massacre, but the connection he makes in his mind is not reflected on screen.

Ferrara

also picked a heck of a time to stop working with Willem Dafoe. Labeouf makes a

poor substitute, even though it was Dafoe who recommended him to Ferrara. There

are some nice performances in Padre Pio, especially Cristina Chiriac, as

a recent war widow who refuses to grieve, and Salvatore Ruocco as the veteran,

whose advances she spurns, because he works as a foreman for the town’s noble

family. However, Labeouf just cannot find the right key or pitch for Padre Pio,

which is a big problem, since the film is ostensibly about him.

In recognition of the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, I review Topic's CHIMERICA at THE EPOCH TIMES. Review up here.

There was a time when Broadway was the place for horror. It was a very

different Broadway, when the masses could find an afternoon’s entertainment for

the change in their pocket. It was also a very different horror, with plays

like John Willard’s The Cat and the Canary and Adam Hull Shirk’s The

Ape supplying a Scooby-Doo-style “rational” explanation (and a lot of

killers in animal costumes). Horror has returned to Broadway, but the sensibilities

are more contemporary and the terrors are much more explicit than those of the

1920s. Unfortunately, ticket prices also conform to 2020’s expectations. Frankly,

getting snowed-in with a creepy family in the isolated cabin is bad in any

genre, but the implications are especially fearful in Levi Holloway’s Grey

House, directed by Joe Mantello, which officially opened last night on Broadway.

Technically,

their car hit a deer, but it seems like an unseen force is mysteriously guiding

Max and Henry to cabin in the woods. It is bitter cold out and Henry’s

banged-up leg needs tending, but the modest home still feels sinister. Soon,

the couple learns it is the abode of four pre-teen-to-teenaged girls and a silent

young boy, who all have a rather strange relationship with Raleigh, their

presumptive mother.

It

is the 1970s, but all the girls behave like they stepped out of an earlier era.

However, Henry quickly takes to the family’s medicine of choice: mysteriously

glowing moonshine, each batch of which carries a man’s name. The couple is in

big trouble, which they sort of recognize, but they do not realize how bad things

are until the girls invite Max to play their sinister (and possibly lethal) games.

The

producers of Grey House can hyphenate its categories all the like, but

there is definitely horror in there. There is even a spot of gore, which would

be modest by Evil Dead standards, but is quite impressive for a live

stage drama. In fact, there are a lot of clever visual effects that might not

be prohibitively expensive or complex, but look really impressive from the

audience’s perspective. There are things that suddenly shine or appear and

disappear that create a potent atmosphere of mystery and dread. Frankly, some

of revelations is Grey House are more shocking than they would be in a

movie, because as a play, you are seeing it “live.”

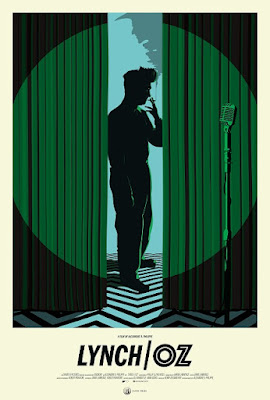

The line "I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore” has become an easy

shorthand quote to suggest a character’s old assumptions about how the world

works have just been turned on their head. It is the sort of thing David Lynch’s

protagonists might say. Maybe they did. I honestly don’t remember if that

precise line was included in the super-cuts of Wizard of Oz allusions seen

throughout Alexandre O. Philippe’s latest cinematically-themed documentary.

However, it should be reasonably safe to conclude Lynch has seen the 1939

classic fantasy and it made some kind of impression on the auteur after watching

Lynch/Oz, which opens this Friday in New York.

Evidently,

film critic Amy Nicolson and genre filmmakers Rodney Ascher, John Waters, Karyn

Kusama, Justin Benson & Aaron Moorhead, and David Lowery having been thinking

about Oz as an important source of Lynch’s inspiration for some time, because

they each get one section of the film to draw their connections.

Frankly,

they all make a very compelling case—so much so that Lynch/Oz will have

most viewers completely convinced after the first part. However, there are five

more sections, which largely repeat the same points. After a while, all the Oz-like

motifs in Lynch’s oeuvre, such as the red shoes, mysterious curtains,

doppelgangers, and the porous boundaries between dreams and reality, become repetitive.

We get it. Lynch definitely alludes to Oz in many of his films. Case closed.

Indeed,

Lynch/Oz shares the prime fault of Philippe’s previous documentary, The Taking, in that all his participating commentators share the same opinions

and make the same arguments. There are no crazy outliers (as there were in

Ascher’s Room 237) or dissenting opinions (as in Mark Hartley’s Not Quite Hollywood). It is just the same talking points, repeated five times

over. Waters gives it more of a personal spin and Ascher takes a more macro

perspective on Oz’s overall influence on American cinema in general, but

there are no conflicts in the six analyses Philippe presents.

When it comes to amateur sleuths, Neve Kelly is unusually highly motivated,

especially for a Gen Z’er. The murder she is trying to solve is her own. Obviously,

she is at a bit of a disadvantage as a ghost, but there are a few people who

can see her. Regardless, there is a murderer out there, who does not want to be

caught in The Rising, Peter McTighe’s eight-episode British remake of the

Belgian series Hotel Beau Sejour, which premieres tonight on the CW.

It

is not initially shocking the Kelly did not make home the morning after her

final motor-cross race of season. When she wakes up in the lake, she is still

not aware of her death. Unfortunately, due to the booze at the party and the

trauma of the murder, she has no memory of what was done to her, or by whom. At

first, nobody seems to be able to see her, but soon she realizes her hard

boozing father can. Of course, he cannot believe his eyes, but with a little

effort, she convinces him of her presence. Then she also realizes Alex Wyatt,

her boyfriend’s cousin can see her too. Eventually, it will get to the point

where it would be easier to just list who can’t see Kelly, but frustratingly

for her, her grieving mother Maria Kelly never can.

Weirdly,

the issue of who can see Kelly and why gets worked out to an acceptable extent.

However, there are a lot of other questions about the mechanics of “death” that

are never satisfactorily explained. Kelly still needs to take her motorbike to

get across town, but nobody can see her driving it, except her well-lubricated

dad. When she smashes up a vase, but it appears just as it was, once the living

turn their gaze towards it. Frankly, the way dead Kelly interacts with the physical

world makes almost no sense. Instead, it seems deliberately fluid, simply to

help advance the storyline. Yet, the persistence of those nagging issues of

logic constantly distracts from the drama.

There

is a lot in The Rising that comes perilously close to genuine silliness.

Still, the series has its creepy moments, especially when Kelly links her

murder to the previous disappearance of woman, whose body was never recovered. Matthew

McNulty and Emily Taaffe are also both excellent as Kelly’s divorced parents,

who deal with their grief in very different ways. Alex Lanipekun is also a

standout (in a good way) as Kelly’s distraught stepfather, Daniel Sands, whose own

grief is unfairly ignored and belittled by his overwrought wife.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt should be studied for one thing above all: how to serve

as commander-in-chief during wartimes. Throughout WWII, Roosevelt maintained a

long-term strategic perspective. Today, if over 7,000 American service

personnel were killed in a single battle, the press would probably call for the

President to be impeached, but that is exactly what happened at Guadalcanal,

relatively early in the war. Director Malcolm Venville and producer-chief

talking head Doris Kearns Goodwin again use her book Leadership in Turbulent

Times as a road-map for the three-part FDR, which starts tomorrow

night on History Channel.

As

in the previous Abraham Lincoln and Teddy Roosevelt, Venville incorporates

dramatic interludes to illustrate episodes from Roosevelt life under discussion.

In this case, the casting of Christian McKay (who was terrific playing Orson

Welles in Richard Linklater’s Me and Orson Welles) is the best of the

History Channel hybrid docs, since Graham Sibley played Lincoln. With the help

of some makeup, McKay convincingly portrays the young and dashing Roosevelt up

through his tragic Yalta decline.

Kearns

and her colleagues’ commentary on FDR’s early years is somewhat revealing. It

probably is not well known how deliberately FDR patterned his political career

on that of his fifth-cousin, Teddy Roosevelt (jumping from the state

legislature, to assistant secretary of the Navy, and then to the governorship).

In fact, Eleanor Roosevelt was more closely related to TR, since she was his

niece. Kearns and company largely admire FDR’s politically astute tight-rope

walking, when he served as a prominent surrogate for Woodrow Wilson’s presidential

campaign, against TR. However, they never hold him to account for supporting Wilson,

who did more than any other president to institutionalize racial segregation.

Unlike,

Teddy Roosevelt, which includes ample criticism of TR, FDR features

nothing but praise for its subject (except for maybe a few minutes on the

Japanese-American internment). The lack of diverse perspectives is glaringly

obvious during talk of the New Deal. Frankly, many of FDR’s policies prolonged

rather than fixed the Great Depression. The timeliness of FDR’s court-packing

debacle is also lost on the collected historians.

Yet,

in terms of political biases, the worst over all three episodes is the

selective editing that makes Wendell Wilkie, the 1940 GOP presidential

candidate, look like an isolationist, when he was probably even more of an

internationalist than FDR, at that time. Seriously, Goodwin should be embarrassed.

They went from being stoner draft-dodgers to running sweatshops in Southeast

Asia, allegedly. Presumably, this Australian import series does not get that

far. As a highly fictionalized, twentynothing soap opera riff on the early days

of the Billabong and Quicksilver surf fashion rivalry, it will encourage most

viewers to wear Ocean Pacific instead. Creators Michael Lawrence, John Molloy,

and Liz Doran take us back to the birth of board shorts in Barons, which

premieres Monday on the CW.

Snapper

Webster built his surfing goods line off the proceeds of his mates’ annual surfing

expedition to Bali, if you know what I mean. He is tightly controlling of the

business, yet perversely averse to risk and change. That frustrates his best

mate Bill “Trotter” Dwyer, who is brimming with new ideas.

Inevitably,

he sets out on his own, with the help of his newlywed wife Tracy, who is

awkwardly Webster’s ex. To compile the insults, they launch their company with

seed money Tracy borrowed from Webster, ostensibly for her wedding. Webster

takes it badly, launching a very public feud. Meanwhile, several of their

mutual friends are sweating out the draft. The vociferously anti-war Dani Kirk

has even offered herself for sham marriages, even while she questions her own sexual

identity, especially after meeting acclaimed surfing photographer Shirley

Kwong.

Barons

would

have been much more watchable if it had more Endless Summer and less Hair.

Honestly, its New Left anti-war politics look overly simplistic and self-serving,

especially when considering the subsequent plight of the Vietnamese Boat People

and the oppressive corruption of the current Communist regime.

Unfortunately,

the subplots focusing on deserters and questioning draftees detract from what

could have been a deliciously ironic depiction of the peace-and-lover surfers

growing into cutthroat capitalists, at least judging from the first two

episodes, “Paradise Lost” and “Gone Surfing.” Instead of embracing the

characters’ inner Gordon Gekkos, Doran and co-writers Matt Cameron and Marieke

Hardy basically give us a shallow “Dawson’s Wave.”

Father-son relationships are often complicated. A foreign occupation will not make it any

easier for Jurgis Pliauga and his adopted son Unte. The young man is drawn to

the more proactive means of resistance advocated by Deacon, a leader of the

Forest Brothers partisans, whom he starts to see as a competing father figure. In

contrast, his father prefers to play dumb, drag his feet, and even hide, if

necessary, when the new occupying authorities come calling. Of course, tragedy

comes for all men of good conscience in Sharunas Bartas’s In the Dusk,

which premieres today on Film Movement Plus.

The

War is over, but the Lithuanians would hardly know it. From their perspective,

Soviet uniforms have simply replaced those of the Germans. Supposedly, they are

now part of the Soviet Union, but the reparations and protection money the

Soviets extort from them clearly imply their lowly position in the Soviet

hierarchy. As the owner of a sizeable farm, Pliauga is a prime target for their

shake-downs and his lazy farmhand Ignas also expects to receive part of his

employer’s land holdings, through the promised socialist distribution.

Both

Pliauga and Unte have social and commercial dealings with the rag-tag band of

partisans in the forest. Increasingly, Unte is swayed by Deacon’s greater

intellectual understanding of communism, democracy, and the Cold War, as well

as his willingness to fight for Lithuania’s freedom. However, Pilauga is

instinctively cautious. When the local troops come looking for him, the old man

hides in a secret room hidden in his barn, which obviously evokes memories of

those who hid from the Germans in a similar fashion.

In

the Dusk is

definitely an intentionally slow and deliberate film, but it is more accessible

than Bartas’s previous film Frost. Through the former, we witness the

long, slow death of innocence, experienced by Unte and anyone else who might have

hooped for a better life under the Soviets. The Forest Brothers are often rude

and crude, but they are not wrong about the Soviets.

Neither

is Pilauga. Watching the tragedy unfold, it is clear the partisans and the

farmers needed a more widespread, more coordinated, and more flexible campaign

of resistance. Of course, nobody looks worse than the Soviets, who are sadistic

torturers. Yet, they clearly do not believe their purported ideology either.

They just cynically mouth the right platitudes, while practically rolling their

eyes.

Inevitably,

it all ends in heartbreak, unless you are Putin or one of his Western amen

chorus, like Chomsky or MTG. This is a brutally realistic film that is rooted

in the muddy muckiness of the forests and farms. Cinematographer Eitvydas

Doskus makes it all look appropriately dark and ominous. Yet, Bartas still gets

some terrific performances from his cast, particularly Arvydas Dapsys, as the

cagey but sadly dignified Pilauga.

Maybe Ruja's famous artist father Pakorn used lead-based paint. For some

reason, his most notorious paintings seem to kill their owners. Technically,

they are hers now, but she cannot wait to sell them, for several reasons. Her

daughter Rachel urgently needs eye surgery, but she is also just plain uncomfortable

having them around. She has just cause to be uneasy in Surapong Ploensang’s Cracked,

which releases tomorrow on VOD.

Even

after her husband’s death, Ruja wanted nothing to do with her father.

Collectors might think he was a genius, but she knows he was a sadistic jerk. She

can’t remember all the details, but she knows he was bad. Nevertheless, she needs

the inheritance when his dealer, Wichai, informs her of Pakorn’s death.

Rather

ominously, a related pair of late career masterworks were returned to the

estate after the owner’s family-annihilation-suicide. Ruja won’t even let

Rachel in her dad’s studio, even before she sees the sexually suggestive portraits

of his late model, Prang. To maximize the re-sale value, Wichai’s son, Tim

restores the cracking areas. As he fiddles with the canvas, he finds evidence

of hidden portraits underneath Prang, which intrigue him considerably more than

Ruja. Intuitively, she suspects the paints are related to the supernatural

forces that have been harassing her and Rachel.

Cracked

(as

in chipping paint) is a lot like many other Thai and Southeast Asian horror

films, but Ploensang’s execution is super-effective. The film oozes atmosphere,

thanks in large measure to some terrific art and scenery design. The creepy old

manor is a perfect horror movie setting and the pair of paintings look like

they radiate pure evil.

This Australian cult has its members undergo recorded confessions, or

so-called “clearings,” which provide them ample blackmail fodder, should anyone

ever step out of line. Gee, can you imagine any purported cults with ties to

Hollywood engaging in similar practices? Yet, for Australian audiences, the

cult matriarch’s “children,” amassed through questionable adoptions and foster

arrangements, would immediately recall “The Family,” led by Anne

Hamilton-Byrnes. In the case of Adrienne Beaufort’s cult, things start to fall

apart when an over-zealous member kidnaps a little girl, who refuses to be

indoctrinated into the “family.” The mystery of young Sara’s fate will haunt

every character in writer-creators Matt Cameron & Elise McCredie’s The

Clearing, which premieres today on Hulu.

Sometime

in the past, Freya (as she now calls herself) was traumatically associated with

the cult based at Bronte-esque Blackmarsh Manor. She got out, but the scars

remain, especially when news of a child abduction triggers (the word is actually

appropriate in this case) bad memories.

Tamsin

Latham is a true believer, unwaveringly devoted to Beaufort, but her initiative

has been disastrous. No matter how hard they try to brainwash Sara, she refuses

to accept her new name, “Asha,” or her new “mother.” Beaufort’s favorite “child,”

possibly her own biological daughter, Amy, was supposed to win Sara/Asha over.

Instead, the little girl’s deep sense of self raises questions in Amy, at the

worst possible time—right before her first ritual “clearing.”

Cameron

and McCredie play a lot of devious games with the timeline that might be easier

to guess from this review than from watching The Clearing from the

start, despite my good faith efforts to be vague and misdirecting. However,

they are not simply being clever for the sake of cleverness. By the time you

get through the first four episodes provided for review (out of eight), you get

a potent sense of how the sins of the past continue to exert an evil influence

over everyone in the present, especially since several characters cut their own

deals, rather than holding fast to their principles.

Without

question, Miranda Otto is the star of Clearing as the chillingly regal

Beaufort. She makes the cult leader’s Svengali-like control over people totally

believable and absolutely terrifying. Likewise, Kate Mulvany might be even

scarier as the sadistic Latham, who seems to have joined the cult for the

opportunity to bully children. Guy Pearce is also pretty creepy and clammy as Beaufort’s

consigliere and theoretician, Dr. Bryce Latham, but it is still not clear why

the role was meaty enough to attract the well-known thesp.

This isn't just a series finale. It is a universe finale, marking the end of

the interconnected Arrowverse shows on CW. Either Superman & Lois

or Gotham Knights might still eke out a renewal, but they are both

set in different DC universes. Logically, a lot of familiar faces come back for

the “final run,” which is fortunate, since Barry Allen will need plenty of help

saving the current timeline in “A New World, Part Four,” the final episode of The

Flash, airing tonight on the CW.

Obviously,

a lot has happened since “It’s My Party and I’ll Die If I Want to,” much of it

involving time and speed. It seems a lot of the Flash’s old nemeses, living and

dead, have been brought together, to combine their powers and harness the speed

equivalent of The Force to defeat Team Flash. It would be deemed a spoiler to

name names, but if you have only watched a few cherry-picked episodes this

season, they might not be immediately recognizable. Regardless, they are all

speedy.

Meanwhile,

Iris West-Allen is in the hospital poised to deliver Baby Nora. The

long-awaited arrival of babies is a staple of series finales. Frankly, “New

World, Part Four” includes pretty much each and every one you could think of,

except the Seinfeld-style clip-package trial. Honestly, The Flash’s finale

is more satisfying, for exactly that reason.