We need to get horror film directors some sort of group subscription to

Discovery+, because they need to start developing healthier relationships with

food. You would think there would be plenty of healthy eating in this film, because

Simi’s Aunt Claudia is a nutritionist, but the ominous countdown to Easter dinner

clearly implies something awful will be happening in screenwriter-director Peter

Hengl’s Family Dinner, which screens during this year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

Tired

of getting bullied over her weight, Simi invited herself to Aunt Claudia’s rural

Austrian farm over Easter break, in hopes she could get some personal

weight-loss mentoring. The thing is, Claudia (an aunt by a marriage-now-divorced)

is not as welcoming as Simi hoped—but her new husband Stefan is weirdly

hospitable. Her cousin Filipp is probably downright hostile, but he isn’t

getting along so well with his mother and Stefan either.

Despite

some initial misgivings, Aunt Claudia agrees to help Simi, but her rigorous

program borders on the draconian. It seems physically unhealthy and the mind

games grow increasingly sinister. On the other hand, Stefan finds Simi more

useful than Filipp during a hunting trip, so she has that positive

reinforcement going for her.

There

is a lot of slow-boiling in Family Dinner, but it is pretty clear what

is it all heading towards. Not to be spoilery, but if you really think about the

title, it is a dead giveaway. Unfortunately, Hengl expects the climax will be

so shocking, it will make up for the slowness of the build and the lack of

significant plot points.

Early 1991 was an opportune time to be a film student in the Baltics, because

history was exploding daily. It was also a dangerous time for the same reason.

Jazis generally supports Latvian independence from their Soviet occupiers, but

he has yet to mature to the point he can fully appreciate the gravity of the

moment in Viesturs Kairiss’s January, which screens during this year’s

Tribeca Film Festival.

Jazis

wants to be the next Tarkovsky, which would ordinarily alarm most parents, but

his anti-Communist mother is fine with it, along as he gets a draft deferral

from his film school. The last thing she wants is to have her son in the Soviet

army, potentially in harm’s way, while putting down democratic opposition

movements. His father also basically agrees, even though he is a Party member. Unfortunately,

Jazis’s drive and talent level will complicate matters.

For

a while, his affair with Anna, a pretty fellow film student awakens some

passion in him. However, when she falls under the influence of a famous

filmmaker, Jazis spirals into depression and apathy. Yet, maybe the Soviet

military’s attempts to stifle Baltic activism for independence might awaken him

from his lethargy.

Kairiss

skillfully uses a textured lo-fi style (including Super8), integrated with genuine

historical archival footage, to recreate the tenor of the early 1990s in the

Baltics quite vividly and evocatively. You really get a sense of the tension

and potential violence that was literally hinging in the air. In one telling

moments, Jazis asks an elderly woman if she was scared to deliver the food she

baked for demonstrators. “No, I’ve been waiting 50 years for this,” she tells

him.

January

is

highly effective time capsule and mood piece, but Jazis is so moody and sulky,

we hardly get a sense of any character there within him. Arguably, many of the

minor figures, like Jazis’s parents, resonate more than he and his film school-mates.

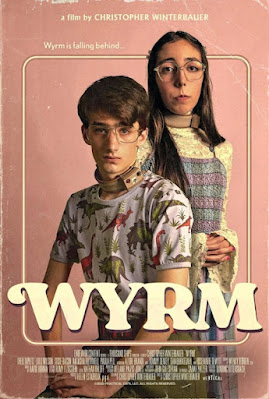

In our world, there is already plenty of pressure on geeky middle school

kids trying to ask someone out. In this alternate 1990s, Wyrm Whitner could be

held back if he doesn’t get to first base fast. His electronic monitoring

collar will know whether he lands that first kiss or not. Of course, his weird

family drama is hardly helpful in screenwriter-director Christopher Winterbauer’s

eccentric coming-of-age fantasy, Wyrm, which releases today on VOD and in

theaters.

Whitner’s

brother Dylan was the jock-hero of his high school, but he wasn’t such a great

brother, or even much of a person. Nevertheless, Wyrm doggedly records audio

tributes for Dylan’s one-year memorial, perhaps as an excuse for the embarrassing

collar obviously still affixed around his neck. Unfortunately, his older sister

Myrcella is not helping, even though she hangs out with Izzy, the new girl

across the street. Instead, she is more interested in earning “credit” with the

Norwegian exchange student and writing poison pen letters to their classmates.

Poor

Wyrm is pretty much on his own, because neither of his parents are much of a

presence in their lives anymore. Instead, their slacker Uncle Chet and his

immigrant girlfriend Flor handle most of the parental duties. Maybe they aren’t

perfect, but at least they are trying.

Wyrm

works

surprisingly well because Winterbauer maintains the logic of the “No Child Left

Alone” system, while not boring us with the deep dive details. Admittedly, the

obsession with preteens’ sexual development feels a little creepy, but the Last-American-Virgin-style

drama is weirdly compelling. Perhaps inadvertently, it also maybe argues how

mandates can be counter-productive. (It is also worth noting the actual “No

Child Left Behind” program was not designed to put pressure on kids. It was

intended to measure the effectiveness of their teachers, who started stressing

their kids out to perform well, just to cover their butts, so riffing on its

name in this context really isn’t fair.)

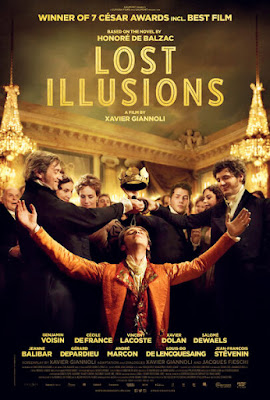

At this point, we really shouldn’t accept newspaper reports as reliable

primary sources. The Washington Post’s embarrassing controversies

regarding stealth edits and misleading corrections are nothing new. Their

imploding newsroom could totally relate to the poisoned-pen scribes at Le

Corsaire-Satan. They traffic in gossip and sell their reviewers’ critical

judgement to the highest bidder. The editor, Etienne Lousteau definitely shapes

its stories to fit his preconceived “narratives,” until someone pays him to

slant them differently. That is just fine with Lucien de Rubempre, until he

finally believes he can attain the noble stature he believes is his birthright in

Xavier Giannoli’s Balzac’s adaptation, Lost Illusions, which opens

tomorrow in New York.

When

people want to annoy de Rumpre, they call him Chardon, because that is

technically his name and the name of his absent father, who ruined his

blue-blooded mother. Like it or not, he is a commoner, so he should not be seen

in compromising situations with Louise de Bargeton, the artistic patron for his

poetry. Nevertheless, she brings him to Paris, risking a scandal that her older

admirer, the Baron du Chatelet manages to suppress, at de Rumpre’s expense.

He

was supposed to slink home to the provinces in disgrace. Instead, de Rumpre

starts writing for Lousteau’s rabble-rousing anti-monarchist newspaper, quickly

adapting to its advertorial ways. Yet, the corrupted poet cannot resist the

temptation of vague promises to restore his family’s lost title.

While much of what transpires is tragic, the caustic characters and their unrestrained

cynicism makes the film play more like a razor-sharp satire. Obviously, the

portrayal of the media as deliberate misinformation peddlers could not be timelier.

Given it was culled from Balzac’s The Human Comedy novel-cycle, Lost

Illusions also clearly establishes the long-standing tradition mercenary

journalistic ethics.

Tony Hillerman was a decorated WWII vet who largely popularized Southwest westerns. Nice to see a well-produced new take on his hardnosed Lt. Joe Leaphorn. EPOCH TIMES review of DARK WINDS now up here.

Apparently, this small island community has brought New England-style weirdness to a

Florida key. It would seem even cults built around Lovecraftian horror find the

Florida economy more inviting. Marie Aldrich’s movie star mother made it clear

she never wanted to return, not even to be buried. That is why the daughter was

so shocked when her mother’s will stipulated she be laid to rest in the island’s

cemetery. It also makes her especially annoyed when she is summoned to the

tourist trap island, by the news her mother’s grave was desecrated. Of course,

someone or something wants to lure her there in Mickey Keating’s Offseason,

which premieres Friday on Shudder.

When

Aldrich arrives with George Darrow, her close-to-being ex, the groundskeeper is

nowhere to be found. The locals are not exactly friendly either. Darrow is

understandably eager to leave the island before the drawbridge closes (or

rather opens) for the duration of the offseason. However, a strange force keeps

steering them into dead-ends.

Keating

is very definitely an up-and-down filmmaker, but Offseason might his

most successful film yet, in terms of crafting mood and atmosphere, even more

so than Psychopaths and Darling. It is also probably his most

polished film, so far.

There

is definitely a lot of Shadow Over Innsmouth vibes going on. The

flashbacks are mostly padding, but the film definitely mines the tight little

island setting for maximum impact. Production designer Sabrena Allen-Biron

notably contributes some memorably eerie analog sets and trappings that really

give the film a distinctive look and texture.

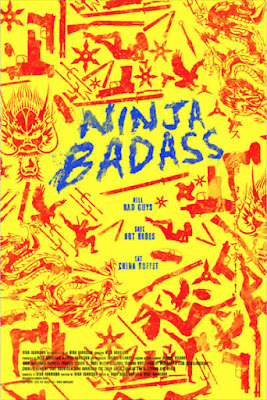

The doughy, pasty-white ninjas of Indiana are about to wage an all-out war.

Who will lose? Eventually everyone, but good taste and dignity will be the

first casualties. Rex isn’t much of a ninja, but he will have to cowboy up if

he wants to save the girl and stop the evil puppy-eating cannibal ninja cult in

writer-director-everything-else Ryan Harrison’s Ninja Badass, which

opens Friday in Los Angeles.

Rex

is a screw-up, who is completely oblivious to his ineptitude. Nevertheless,

when Big Twitty, the leader of the local chapter of the Ninja VIP Super Club,

kidnaps the attractive woman from the pet store (along with their stock of

puppies), Rex decides to “rescue” her back. Fortunately, Haskell, a relatively

law-abiding ninja, agrees to tutor him, for revenge, after Big Twitty tears his

arm off.

Of

course, neither Rex or Haskell can walk and chew gum at the same time. However,

Big Twitty’s estranged daughter Jojo is a match for her father. She has no

illusions regarding Rex’s idiocy and incompetence, but she still reluctantly

teams up with him.

Basically,

Ninja Badass was made for people who find Troma movies too sophisticated

and pretentious. It is chocked full of crude gore and deliberately cheesy

superimposed special effects—including puppies going into the blender.

Seriously, it makes The Greasy Strangler look like a drily witty Noel

Coward comedy.

There

is little point in submitting Ninja Badass to an in-depth critical

analysis. It is meant to be ridiculous and shocking, which it is. However, a

film like this running over one hundred minutes is just excessive. Honestly,

after one hour, we totally get the joke and then some.

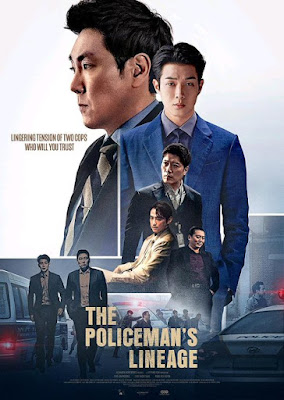

This Korean cop thriller is based on a Japanese novel and tries for some serious old

school Infernal Affairs-style Hong Kong vibes. For third-generation

cop, Choi Min-jae, the line between right and wrong is straight as an arrow and

clearly demarcated. For his new boss, Park Kang-joon, that line is wavy and

fuzzy, but fortunately he always has an innate sense of where it is. Choi is

not so sure, which makes his new assignment rather tricky in Lee Kyoo-man’s The

Policeman’s Lineage, which releases today digitally.

Choi

just blew a prosecution on the stand, because he would not lie or dissemble

regarding the rough treatment of the accused. He would not appear to be a good

candidate for Kang’s team on paper, but Internal Affairs transfers him, to serve

as their undercover source anyway. They know Kang will take Choi, because he

has a connection to the naïve cop’s father.

It

turns out the death of Choi’s father remains surrounded in rumors and innuendos.

Both Kang and AI will try to play him, by promising to reveal all. However, as Choi

fils pursues his investigation of Kang, he finds plenty of controversy and

departmental politics, but not the smoking guns he expected.

Lineage

does

not quite rank with the best of Korean thrillers, but for the most part, it is respectably

hardboiled and entertainingly cynical. Bae Young-ik’s adaptation of Joh Sasaki’s

novel tries a little too hard to over-complicate the narrative and all the

behind-the-scenes secret cabal maneuvering sometimes feels a little too pat and

forced.

What happens when the human world encounters that of mystical Diwata folk

spirits? Human authorities naturally try to regulate them and their magic out

of existence. Yet, for one mortal, Diwata magic might hold the only hope for

treating his mysterious ailment in After Lambana, written by Eliza

Victoria and illustrated by Mervin Malonzo, which goes on-sale today.

Conrad

Mendoza de Luna does not know it yet, but there is a significant connection

between him and Ignacio. He just knows him as a grateful IT client, who might

have sources who might provide underground medication for the so-called “Rose”

disease, wherein physical flowers start laying roots, until they bloom through

the skin. It is not always fatal, but de Luna’s is located right over his

heart.

Magic

diseases seem to demand magic cures, but any form of spellcasting is now

illegal now that the gateway to the Diwata realm of Lambana has been forcibly

closed. Those who were in the mortal world at the time must now live in

permanent exile. De Luna will meet several, while following Ignacio through the

back alleys and midnight markets of Metro Manila.

After

Lambana starts

in a noir vibe, but it slowly unfolds into folk-inspired fantasy. Victoria’s

intriguing world-building never feels like mere exposition, because it is so

richly archetypal, and yet grounded in the various traditions found throughout

the Philippines. She convincingly depicts the culture clash between the

materialist mortal world and the magical Diwata realm. It is exactly the sort

of vision of an intersection of the human and the fantastical that the film Bright

should have realized better (but didn’t).

Rondo Hatton honorably served his country in WWI, but his name became

synonymous with villains and monsters. Due to his acromegaly, his was often

cast as hulking brutes, including “The Creeper,” in a few late classic

Universal Monster movies. The pathos of Hatton’s life fascinated several young

fannish future filmmakers, including Robert A. Burns, who is best known as the

art director of the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills

Have Eyes. Joe O’Connell tells both their stories in the dramatic-hybrid

documentary Rondo and Bob, which releases tomorrow on VOD.

Although

Hatton’s acromegaly started manifesting after he was admitted to a field

hospital, it was unrelated to the mustard gas attack he had been caught in. Eventually,

his first wife left him, but he went back to his work as a Tampa reporter. He

met his second wife while on assignment at a local society function. She would

have been the obvious choice to be a movie star, but the studio saw Hatton as a

possible replacement for Boris Karloff.

In

addition to being one of the foremost authorities on Hatton, Burns was also the

guy who put all the creepy stuff in Chainsaw Massacre, like the bone

furniture and the chicken in the birdcage. Unlike Hatton, he was apparently somewhat

standoffish around people. One family member diagnosed on the spectrum

speculates Burns might have been too. Regardless, O’Connell’s subjects contrast

greatly, with one looking menacing, but being a wonderful person inside, while

the other looked like anyone else, but was hard to get to know.

As

a result, the Hatton segments are dramatically more compelling. Yet, probably

more time is devoted to Burns, because there is more available material (including

his unreleased proto-found footage microbudget horror film, Scream Test).

Unfortunately, that makes the film feel somewhat unbalanced. We want to spend

more time with Hatton and his second wife, Mabel Housh, because O’Connell and

his cast humanize them so compellingly.

You would think film and television writers would often "rip-from-the-headlines" reference some of

the biggest stories of late 1980s and early 1990s, like say the First Gulf War,

the Fall of the Berlin Wall, and the dissolution of the Soviet Bloc. Yet, you

will find precious few dramas addressing the Tiananmen Square Massacre, despite

audiences’ familiarity of the iconic images of Tank Man and the Goddess of

Democracy statue. It is slim pickings, but the Canadian X-Files knock-off

PSI Factor joined MacGyver and Touched by an Angel, by

producing the Tiananmen-themed episode “Old Wounds” (S3E13), which currently

streams on multiple sites.

Honestly,

this show wasn’t very good, but the premise of “Old Wounds” is somewhat

interesting. Matt Prager’s paranormal investigative team has been summoned to look

into an incident at a tech firm with shady government connections. Adia Carling

was testing an immersive VR game when she suffered real world injuries during

the in-game battle. Weirder still, wounds spontaneously healed.

The

team quickly sleuths out Carling is not from Hong Kong. She is, in fact, an illegal

alien living under an assumed name, who was imprisoned and tortured in China

for her role in the Democracy protests. Somehow, the VR game reopened the old wounds

she suffered while in custody, including the horrific burning of her

left arm. She has the psychic powers to physically heal them, but the team’s

good Dr. Anton Hendricks must hypnotize her, to help her heal her emotional

wounds.

Ideally,

one would prefer to see a serious subject like the Tiananmen Square Massacre

addressed in a more reflective, less exploitative manner, but there are not a lot

of examples out there. Anyone who knows of a Tiananmen Square-themed TV episode,

beyond this MacGyver, or Angel, please shoot me an email. Writers

Jim Purdy & Paula J. Smith treatment of the Massacre and the subsequent

brutal crackdown are not exactly inspired, but director Luc Chalifour manages

to convey the cruelty of CCP torture techniques, while adhering to commercial

broadcast standards.

As a result of the CCP’s draconian “National Security” Law, Hong Kong

residents can no longer safely watch this Frontline documentary,

commemorate the events it chronicles, or search on-line for the image it focuses

on. We must remember for them. In fact, the image of the lone man standing in

front of a column of tanks has become an iconic image of courageous defiance in

the face of overwhelming state oppression. Writer-producer-director Antony

Thomas investigates who he was and how the crackdown on the 1989 democracy protests

drove him to do what he did in Frontline: The Tank Man, which is

available on-line.

Unlike

other vital Tiananmen Massacre documentaries (like Tiananmen: The People vs.The Party and Moving the Mountain), Tank Man largely focuses

on events outside the Square, but that rather makes sense, considering the Tank

Man was blocking tanks on the Boulevard leading out of the Square. In fact, one

of the eye-opening aspects of Thomas’s report is the carnage that resulted when

the PLA strafed apartment buildings around Muxidi Bridge with combat-grade ammunition.

Consequently,

Thomas’s talking heads suggest the majority of killings happened at barricades

set up by average working-class citizens to protect the students in the Square.

Yet, the most senseless murders were those of groups of parents mowed down by

the PLA, who had come to the Square desperate to find their children.

Thomas

and company fully explain the circumstances surrounding the historic film of

Tank Man and how determined the state security apparatus was to prevent it

airing in the international media. They also establish how thoroughly blocked

all images of the protests are on the Chinese internet—as well as the

culpability of Western tech firms like Microsoft, Cisco, and Yahoo in aiding

and abetting the CCP’s censorship.

Thomas

also spends a good deal of time examining the vast economic disparities between

the urban super-rich and the rural underclass. They make valid points regarding

the inequality of China’s economic growth, which has been used to justify the

Party’s ironclad grip on power post-Massacre, but it sort of distracts from sheer

courage and abject horror of the events of 1989.

Do not call Kazem by his name. He prefers the honorific “Atabai” (sort of

like “esquire,” but with more clout) bestowed upon him by his provincial Northwestern

ethnic Azerbaijani hometown. The village holds a lot of painful history for him,

especially the arranged marriage of Kazem’s younger sister, which ended badly—for

her and everyone related to her. Years have passed, but the entire family still

carries guilt from her suicide, but nobody more so than their Atabai. After an

extended absence he returns to reluctantly face his tragic past in Niki Karimi’s

Atabai, opening today in New York.

Kazem

has mixed feelings about being home, but he is happy to see his nephew Aydin.

He has real affection for the dopey teen, but we soon figure out the

well-respected Atabai is also controlling his life, as a way to get back at his

sister’s husband. Frankly, Kazem’s relationship with his own aging father is

nearly as fraught with complications and baggage.

The

returning prodigal once loved and lost during his college years—and still

carries the emotional scars. The last thing he wants from his homecoming would

be a wife, despite some rather mercenary interest. Yet, a woman with her own

tragic reasons to avoid intimacy stirs some long dormant feelings in him.

Atabai

is

a messy but heartfelt film about the long-term effects of grief and trauma. It

is easy to identify with Kazem’s family, even though the particulars of their

circumstances are very much Iranian—starting with the arranged marriage of his

sister, at the distressingly youthful age of fifteen. Arguably, Kazem also gets

away with physically lashing out in rage more than he would in Western

countries. Being an Atabai has its advantages, but everyone understands where

that anger and pain is coming from.

Faster-than-light travel doesn’t change people. It just alters the way they experience of time.

That makes it quite tragic for those who don’t want to go, like the poor

shipman involuntarily pressed into service in L. Ron Hubbard’s To the Stars (from

when he was still readable and not yet messianic). Hundreds of years will pass on

that poor soul’s home before he can return, but for Jack Lambert, only twenty

years have passed on Earth since his teenaged girlfriend left for the space

colonies. Now, she is back and she hasn’t aged a day in Erwann Marshall’s The

Time Capsule, which releases tomorrow on-demand.

Lambert

just suffered through the embarrassing implosion of his senate campaign, so he

and his wife Maggie have come to his dad’s old lake house to regroup. They also

need to sell the place, to help pay down his campaign debts. His old pal

Patrice will help with the handywork. The place holds a lot of memories for

Lambert, so he assumes he is seeing things when he spies his old flame Elise,

who doesn’t look a day older than he remembers her.

It

turns out, after ten years of suspended animation space flight, the colony was still

behind schedule, so they immediately sent Elise and her father back to Earth,

on another 10-year flight. Elise remembers seeing teenaged Lambert in what only

feels like a few weeks prior, but now he is a very married, disappointing politician.

Of course, he never got over her. In fact, it was his controlling father who

arranged for their place in the colony. The adult version of Lambert knows he

cannot just pick-up with Elise (even though the film repeatedly tells us she is

eighteen, so nobody freaks out)—but there is still that old chemistry between

them.

Marshall

and co-screenwriter Chad Fifer cleverly use Relativity as their Macguffin and

skillfully skirt the potential pitfalls (there are no inappropriate moments to

gross-out the overly sensitive). It is actually a really smart way build a

character-driven story atop a science fiction premise. They also shrewdly keep Lambert’s

platform sufficiently vague, so as not to needless alienate viewers.

Today, you can find the name “Genghis Khan” everywhere throughout modern

Mongolia. He sits magnificently astride the monumental equestrian statue

erected in 2008, which has quickly become one of the nation’s top-drawing (and

literally biggest) tourist attractions. Yet, during its years as satellite-state

of the Soviet Union, Genghis Khan was demonized in propaganda and banished from

public discourse. A lot of good change came quickly to Mongolia, but the nation

is still struggling to process subsequent social upheavals. Director-cinematographer-co-producer

Robert H. Lieberman chronicles Mongolia’s glorious history and examines its future

challenges in Echoes of Empire: Beyond Genghis Khan, which opens in

select theaters this Friday.

Ironically,

everything bad you might think about Genghis Khan (a.k.a. Temujin) is largely

the result of Communist disinformation. Yes, he was a conqueror of kingdoms,

whose empire spanned three times the territory Alexander the Great controlled

at his peak. However, as he incorporated new people into his empire, he extended

to them rights they never had. Arguably, Genghis Khan “invented” the right of

religious liberty, as we know it today. He also forbade the kidnapping of women

and established an early form of diplomatic immunity.

Yet, the Communist regime jealousy suppressed celebration of the Mongolian

national hero. (For comparable hypotheticals of a nation erasing its cultural-historical

legacy, imagine the United Kingdom trying to cancel King Arthur, or America

forbidding mention of George Washington, neither of which quite captures the

scope of the Communist Party’s negation of Genghis Khan.)

One

historical episode explained in the film that has particular resonance for our

world today came relatively early in Genghis Khan’s career of conquest, when

the Uyghur people sent an emissary, inviting his invasion of their lands, in

order to liberate them from their oppressors. It came as a surprise to the Mongol

leader, but he obliged.

The

film also archly observes how many commissars from the early Communist era met

suspiciously premature demises—and openly invites the audience to make the

obvious conclusions. Even more fundamentally, when watching Lieberman’s film, viewers

will be immediately struck but the sensitive geographic position Mongolia

occupies, as a functioning democracy nestled between China and Russia.

It

is pretty clear Mongolia is a country Americans should be thinking about much

more than we are. Although Mongolians have pretty forcefully repudiated the

Twentieth Century Communist era (the 130-foot Genghis Khan memorial says so,

loud and clear), they still have to maintain cordial relations with Russia.

They also have considerable cultural ties, having adopted Russian tastes in

opera and ballet, to a surprising extent, as Lieberman and company vividly

illustrate.

Furthermore,

Americans can well relate to Mongolia’s current struggles with increased

urbanization and a widening gap between the city life of Ulaanbaatar (UB) and

the traditional way of life on the steppe. Lieberman takes viewers into the

gers (or yurts) of traditional herders, which look warm and cozy on the steppe.

However, he also illustrates the downsides to coal-heated ger-living in the urban

tent-cities of nomads who have been recently force to relocate to UB.

Yes, all parents are embarrassing, but Nikuko is in a league of her own. Yet,

her daughter Kikuko never judges her too harshly, because she understands her

better than even her mother realizes. Life dealt Nikuko a lot of

disappointments, but at least she has her daughter in Ayumu Watanabe’s Fortune

Favors Lady Nikuko, from Studio 4ºC and GKIDS, which screens nationwide

tonight (and opens Friday in select theaters).

Big-hearted

and big-boned Nikuko has a long history of getting involved with the wrong men,

who inevitably took advantage of her. The last was arguably the best of the bad

lot, so Kikuko sort of understood when her mother dragged her to his sleeping

fishing village-hometown, afraid he had fled there to take his own life. They

never found him, but they decided to stay and make a home there.

Nikuko

works for the gruff but protective Sassan at his seafood grill and they rent

his ramshackle houseboat. Boys are not really a factor yet in tomboyish Kikuko’s

life, but she is reasonably friendly with her fellow girls at school. In fact, she

is courted by two basketball-playing cliques, because of her height, but she is

uncomfortable committing to either side. However, her anxiety is probably

really coming from a fear Nikuko will uproot them again.

Despite

being a slice-of-life story (think of as a Japanese Beaches, but with

less weepy melodrama), Lady Nikuko features some wonderfully vivid

animation. The coastal village and surrounding environment sparkle on-screen

quite invitingly. (It is easy to believe this came from the same animation house

that brought us Tekkonkinkreet.) Ironically, there is a far more visual

dazzle in this film than Watanabe’s more fantastical Children of the Sea.

David Cronenberg is catching the Greek Weird Wave, filming his latest in the

ancient but economically depressed nation. Aesthetically, they are perfect for

each other. Body horror meets subversive, extreme anti-social behavior. Yet, according

to Cronenberg’s vision of the future, both the body and society are evolving,

but to what is yet to be determined in Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future,

not the one from 1970, the entirely new and unrelated one that opens this Friday

in New York.

It

is not exactly clear how far into the future this film takes us, or where, but

the environment is vaguely Mediterranean, for obvious reasons. Cronenberg doesn’t

exactly pander to viewers during the prologue, in which a mother smothers to

death her son, for eating the plastic waste basket.

Those

are definitely Weird Wave vibes. Saul Tenser delivers the body horror, but he

calls it art. For years, his body has spontaneously generated new mutant organs,

which his partner Caprice surgically removes during their performance art

programs. Each organ is considered a work of art that the newly formed National

Organ Registry duly records. Not surprisingly, the Registry’s two employees,

Whippet and Timlin, are among Tenser’s biggest fans.

Lang

Dotrice also closely follows Tenser’s work. In fact, he offers Tenser a concept

for his next show: autopsying Dotrice’s son, Brecken, who was killed at the

start of the film. Dotrice leads a mysterious cult that has genetically modified

themselves, so they can only consume plastic waste. Brecken was the first of

their progeny to naturally develop their ability to digest plastic, but he

apparently creeped out his unevolved-human mother.

Cronenberg

definitely brings the gross and the weird, but the story and characters are a

bit sketchy. This is an idea film and a mood piece rather than an exercise in

story-telling to hold viewers rapt. However, the mood is pretty darned moody. Even

though this is the future, everything looks dark, decaying, and fetid, like it

could be part of a shared world with Naked Lunch, while the strange

surgical and therapeutic devices look like they were inspired by the designs of

H.R. Giger.

Viggo

Mortensen and Lea Seydoux are perfectly cast and do indeed create an intriguing

relationship dynamic as Tenser and Caprice. Cronenberg raises some challenging

questions about the roles they both play in creating art, particularly with

regards to the nature of authorship and intentionality.

Unfortunately,

characters like the two mechanics from a shadowy Vogt-like multinational

company, who are constantly servicing Tenser’s feeding chair and pain-relieving

beds could have stumbled out of dozens of uninspired dystopian films. (Frankly,

the sort of bring to mind the Super Mario Brothers movie, which is not a

good thing.) Beyond Tenser and Caprice, the most interesting character might be

Det. Cope of the new vice squad, who is trying to anticipate future crimes

against the body. Welket Bungue portrays his hardboiledness with subtlety not found

anywhere else in the film.

Maurice Flitcroft wanted to be the real-life version of Kevin Costner’s “Tin

Cup,” but he just never played the game very well. Nevertheless, his record-setting

high-score at the 1976 British Open made him something of a cult hero to

frustrated duffers everywhere. After that, the British Open was very much done

with Flitcroft, but Flitcroft was not done with them. His unlikely career gets

the underdog movie treatment in Craig Roberts’ The Phantom of the Open,

which opens this Friday in theaters.

Having

always provided for his wife Jean, their twin sons Gene and James, and his older

step-son Michael, Maurice is not sure what he wants to do with himself as

retirement approaches for the working-class crane operator. Somehow, he gets it

into his head golf will be his thing. He has the ugly clothes, but his swing is

even uglier.

Naturally,

he figures he will enter the British Open, because it looks like a nice tournament

on the telly and because he can. That is why it is called an “Open.” It turns

out there is a lot less paperwork to enter as a professional rather than an

amateur, so that is what he does. Stodgy Keith Mackenzie of the R&A is scandalized

by Flitcroft record high score, so he bans him from future tournaments.

However, loyal Jean encourages Flitcroft to persevere, so he starts devising

ways to enter subsequent Opens under assumed names.

Without

question, Phantom is most entertaining when it revels in the subversive

farce of Flitcroft’s Open capers. His disguise as French golfer “Gerald Hoppy”

is a sequence worthy of Peter Sellars. (It even comes with a Clouseau

moustache.) However, Roberts somewhat loses his way, indulging in some painfully

maudlin family melodrama during the third act. Flitcroft was born to burst

pretensions, rather than be elevated to some kind of tragic hero.

It is one of the highest grossing Indian films of all-time and it was

partly shot in Ukraine, but apparently that didn’t mean much to the government of the “world’s

largest democracy” when Putin invaded. After all, shooting had already wrapped,

on a picture that ironically protests the brutality of British imperialism. In

this action epic, the British probably lose more soldiers than they did at

Bunker Hill. Such an incident would have surely led to a parliamentary inquiry,

especially since a regional governor precipitated the whole mess by abducting a

young girl. That just isn’t cricket, you know? Two legendary early Twentieth

Century revolutionaries form a fictional friendship and team-up against the

British in S.S. Rajaouli’s RRR (a.k.a. Rise Roar Revolt), which

has a special one-day return to American theaters this Wednesday.

Governor

Scott Buxton and his Lady Macbeth-esque wife Catherine happened to hear a young

Gond singer during their trip to Telangana, so they just figured they’d take

her with them as a souvenir. As the “shepherd” of the tribe, it is Komaram Bheem’s

sworn duty to find her and safely bring her back. To do so, he naturally falls

in with Delhi’s revolutionary circles. Unfortunately, his brother comes to the

attention of A. Rama Raju (better known as Alluri Sitarama Raju), who was then

a hard-charging Indian officer, but secretly harbored revolutionary ambitions.

While

chasing Bheem’s brother, Raju stops to rescue an endangered street urchin, with

the oblivious help of Bheem himself. Being men of action, a fast-friendship

blossoms between them, but when Bheem launches his rescue operation, it forces

Raju to make a series of soul-searching decisions.

Despite

the patriotic themes (critics would call RRR jingoistic if it were made

in America), the reason it traveled so well outside of the subcontinent is the

off-the-wall action. The sequences involving CGI-animals might even be a little

too off-the-wall, but perhaps they look better on a more spacious big screen.

Still, our introduction to Raju is quite a barn-burner and incidentally also a

good lesson in crowd control. Arguably, the whole thing morphs into a

super-hero movie during the climax, when they become invested with the powers

of Lord Rama, but it certainly makes for some wild spectacle.

You have to appreciate a celebrity chef who acknowledges the five-second

rule. Julia Child wasn’t above brushing off a little dirt from kitchen mishaps,

which was one of the reasons she was so fun to watch. For years, she was also

the original and only really notable TV chef. If she were alive today, she would

probably have her own streaming channel, but the magnitude of her success in

her time was still no can of corn. Julie Cohen & Betsy West chronicle Child’s

life and career in the documentary Julia, which airs tomorrow on CNN.

Before

she served dinner, Child served her country as a staffer for the OSS, Wild Bill

Donovan’s forerunner agency to the CIA. Her family insists she never did any spycraft,

but that still seems like a good idea for a fictional thriller. Regardless, she

met her future husband, Paul Cushing Child, when they were both posted to

Ceylon. Eventually, his career in the Foreign Service brought them to France,

where she met Simone Beck and started collaborating on Mastering the Art of

French Cooking, an unusually detailed cookbook, intended for American

readers.

Public

television was pretty grim in the early 1960s, but WGBH viewers appreciated how

she livened up a book review program, by demonstrating the proper technique for

making an omelet. As a result, they took a chance on a show of her own, The

French Chef. The best part of the doc gives a behind-the-scenes view of its

early, by-the-seat-of-its pants years. The production process might have been

an adventure, but the show was an immediate hit.

Everyone

gives Child credit for making PBS watchable, yet Public Broadcasting thought it

was time to put her out to pasture in the early 1980s, so she signed with Good

Morning America instead. It is clear throughout Julia that Child was

a shrewd capitalist. However, Cohen & West (whose RBG celebrated

Justice Ginsburg for having a kneejerk political record on the bench, rather than

a coherent judicial philosophy) do their best to transform Child into a

divisive figure, by celebrating her liberal activism.