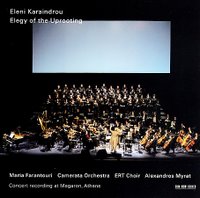

Elegy of the Uprooting

Elegy of the UprootingBy Eleni Karaindrou

ECM New Series 1952/53

110 musicians were assembled for the Eleni Karaindrou concert documented on the double CD Elegy for the Uprooting, including a concert orchestra, choir, an ensemble of traditional Greek instruments, celebrated Greek vocalist Maria Farantouri, and the composer herself on piano. Remarkably, despite the presence of so many, the results are striking for their effective simplicity.

For the Elegy concert, Karaindrou integrated themes she had composed for ten films and two stage dramas, all of which had thematic commonalities. As the title suggests, displacement and mourning figure prominently the works Karaindrou scored, so they coalesce together fluidly.

Karaindrou is best known for collaborating with the filmmaker Theo Angelopoulos, with eight of his films represented in Elegy. His latest film The Weeping Meadow (2004) and an adaptation of Euripides’ Trojan Women are the touchstones, to which she returns throughout the program.

Meadow is a refuge story twice-over. A young Greek girl fleeing 1919 Russia finds shelter with a Greek family. Despite her attraction to the son, bearing him twins, she is forced to flee the unwelcome marriage proposition of the father. “The Weeping Meadow” theme, heard several times orchestrated for French horn, accordion, and strings, is an elegant melody, appropriate to the elegiac concept. The first version (disk 1, track 3) is a dramatic string feature, while the final (disk 2, track 19) is more dirge-like.

The other cornerstone of Elegy is Trojan Women. Karaindrou’s themes and Farantouri’s voice interpret lyrics adapted by K.X. Myris, capturing the sorrow of the imprisoned women of Troy. Selections like “The City That Gave Birth to You” have a more exotic sound, as they incorporate traditional Greek instruments. Hearing them layered under the choir, one can easily envision a Greek chorus standing against a wind-swept vista.

There are many delicate moments in Elegy, like the solo piano performance of “Refugee’s Theme” from Angelopoulos’ The Suspended Step of the Stork, a film about a border town consisting entirely of stateless people. “Dance” is also a haunting theme carried by oboe, from another Angelopoulos film Ulysses Gaze which starred Harvey Keitel as a prodigal filmmaker adrift in the war-torn Balkans.

Karaindrou is a powerful classical composer, though she has been influenced by traditional Greek music, as well as jazz, particularly label-mate Jan Garbarek (although those influences are not pronounced on Elegy). Clearly Karaindrou is inspired by the themes of her film and theater collaborators, having experienced exile from Greece during the 1970’s. Again, what is most impressive is her use of a large assembly of musicians to pare the music down to its essence, achieving emotional and expressive clarity. It is arresting music that rewards repeated listening.