When tragedy strikes, what is your first reaction? Do you rush to help, stay out of the way of rescue workers, or grab your camera? Photographer Robert Polidori did the later documenting the devastation left in the wake of Katrina, with a small selection (24 photos) on view at the Met through December 10th in an exhibit titled New Orleans after the Flood.

True, recording history is an important calling. However, there is something disturbing about Polidori’s pictures beyond and apart from the destruction they show. Much of the work on display and many of the additional photos included in the exhibit catalog capture the wreckage from inside private homes. Viewing them feels like an intrusion into someone’s personal suffering. Polidori uses the addresses of these homes as his titles, which feels like a further invasion of a stranger’s privacy. Particularly intrusive was a photo from a house on Cartier Avenue (number withheld) which showed family pictures, including a woman in uniform, and a now ruined organ, which was probably once the center of family celebrations. One can easily imagine the family on Cartier would feel violated to see their home, including identifiable family photos, on display under their actual street address.

One wonders, did Polidori get permission to shoot in every house he photographed? No details in the catalog (at least not that I saw skimming it in the Museum). Too often it seems people want to use New Orleans residents as props in their political morality play, losing sight of their essential humanity. One certainly sees that kind of vampirism in the Polidori exhibit. Perusing his pictures too often feels unforgivably intrusive, adding insult to the injury suffered by the people of New Orleans.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

Friday, September 29, 2006

Addled Jazz Notes on Lebanon

Sometimes an essay starts off on solid ground, but veers off the tracks in spectacular fashion. Such is the case with David Adler’s “From the Editor” column in the September issue of Jazz Notes (evidently not available online), published by the Jazz Journalists Association.

Starting off strong, Adler criticizes David Murray for the following lyrics he recorded on the World Saxophone Quartet’s Political Blues:

“I’m gonna take the metroliner down to Washington and give them some advice:

Keep your politics to yourself and leave the brown countries alone

Keep your politics for yourself and leave the Third World alone

And while you at it, hit up on your cell phone to warn Abbas about Sharon . . .”

Adler is on solid ground when he writes: “Remarkably, Murray’s lyric was out of date before the track was even mixed. Both Abbas and Sharon are dead—the former politically, the latter clinically.” One could add that actually Abbas really needed a warning about the destabilizing influence of Hamas extremists.

Adler transitions into a discussion of the explosive growth of the blogosphere, and the resulting analysis there of the conflict in Lebanon, writing: “Unsurprisingly, I’ve found the proliferation of opinion on the Mideast war to be both a blessing and a curse, leaning towards the latter.” It is probably asking way to much of Adler to credit Little Green Footballs, but surely exposing the Reuters Photoshop scandal is an important contribution to our understanding of the media in general, and its coverage of the Mideast specifically, is an important contribution which deserves grudging acknowledgment.

Adler ends with a stunning line: “One can hope that the spirit of open cultural and artistic exchange—as practiced by the late Arnie Lawrence, or by Daniel Barenboim and the late Edward Said—will prevail.” What sounds like a nice sentiment, the hope for tolerance, equates Arnie Lawrence with extremist Palestinian partisan Edward Said. The beloved Lawrence really was building bridges between Israelis and Palestinians, as teacher and student bandleader in Jerusalem.

Said was a polemicist who created the precedent in academia for tarring any critic of Islamic extremism as racist and colonial in his book Orientalism. He condemned intellectuals who dared support the war on terror, and was a reflexive critic of Israel. In 1999 Commentary writer Justus Weiner exposed Said’s fabricated history as a refuge from Jerusalem. In truth, his family had been expelled from Egypt for their Christianity.

Equating Lawrence and Said is a highly dubious act of moral juggling. Those looking to jazz journalists for Mideast commentary, are likely to be addled by what they find in Jazz Notes. Better to look to a real resource, like MEMRI.

Starting off strong, Adler criticizes David Murray for the following lyrics he recorded on the World Saxophone Quartet’s Political Blues:

“I’m gonna take the metroliner down to Washington and give them some advice:

Keep your politics to yourself and leave the brown countries alone

Keep your politics for yourself and leave the Third World alone

And while you at it, hit up on your cell phone to warn Abbas about Sharon . . .”

Adler is on solid ground when he writes: “Remarkably, Murray’s lyric was out of date before the track was even mixed. Both Abbas and Sharon are dead—the former politically, the latter clinically.” One could add that actually Abbas really needed a warning about the destabilizing influence of Hamas extremists.

Adler transitions into a discussion of the explosive growth of the blogosphere, and the resulting analysis there of the conflict in Lebanon, writing: “Unsurprisingly, I’ve found the proliferation of opinion on the Mideast war to be both a blessing and a curse, leaning towards the latter.” It is probably asking way to much of Adler to credit Little Green Footballs, but surely exposing the Reuters Photoshop scandal is an important contribution to our understanding of the media in general, and its coverage of the Mideast specifically, is an important contribution which deserves grudging acknowledgment.

Adler ends with a stunning line: “One can hope that the spirit of open cultural and artistic exchange—as practiced by the late Arnie Lawrence, or by Daniel Barenboim and the late Edward Said—will prevail.” What sounds like a nice sentiment, the hope for tolerance, equates Arnie Lawrence with extremist Palestinian partisan Edward Said. The beloved Lawrence really was building bridges between Israelis and Palestinians, as teacher and student bandleader in Jerusalem.

Said was a polemicist who created the precedent in academia for tarring any critic of Islamic extremism as racist and colonial in his book Orientalism. He condemned intellectuals who dared support the war on terror, and was a reflexive critic of Israel. In 1999 Commentary writer Justus Weiner exposed Said’s fabricated history as a refuge from Jerusalem. In truth, his family had been expelled from Egypt for their Christianity.

Equating Lawrence and Said is a highly dubious act of moral juggling. Those looking to jazz journalists for Mideast commentary, are likely to be addled by what they find in Jazz Notes. Better to look to a real resource, like MEMRI.

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Hand-Selling Banned Books

It’s Banned Book Week at independent booksellers. Can you feel the self-righteousness? Neither Booksense nor the American Booksellers Association for Free Expression (ABFFE) recommends much beyond their politically correct favorites. They declined to advocate meaningfully for books that are actually under attack, like The Satanic Verses, whose author still has a fatwa death sentence hanging over his head. So feel free to recommend Rushdie to your local indy bookseller if they are serious about promoting banned books.

There are plenty of books targeted by state sponsored censorship that we should pay tribute to this week. In addition to Rushdie, books like Oriana Fallaci’s The Force of Reason, or Melanie Phillips’ Londonistan have found themselves in the Jihadi crosshairs. In our own hemisphere, Castro has used his police state apparatus for wholesale round-ups of librarians guilty of thinking for themselves. These thought criminals have been guilty of readers and loaning books like Armando Valladares’ Against All Hope: A Memoir of Life in Castro’s Gulag. Want to take a stand for gay rights? Suggest Renaldo Arenas’ Before Night Falls, which exposes the oppressive conditions faced by Cuban gays and lesbians from Castro’s homophobic regime. Unfortunately, many in the book business have turned a blind eye towards Castro’s assault on free expression. Nat Hentoff renounced his ALA Immroth Award for intellectual freedom, when the American Library Association voted down an amendment which would have protested the wholesale arrests of Cuban librarians.

If you want to hand-sell your suggestions to a bookseller, good luck. They should be receptive if they really believe in free expression. However, the Booksense and ABFFE lists clearly do not. They simply reward politically correct titles while ignoring titles literally in the line of fire from Islamic Fascism and Castro thuggery. Independent booksellers ought to start living up to their name.

There are plenty of books targeted by state sponsored censorship that we should pay tribute to this week. In addition to Rushdie, books like Oriana Fallaci’s The Force of Reason, or Melanie Phillips’ Londonistan have found themselves in the Jihadi crosshairs. In our own hemisphere, Castro has used his police state apparatus for wholesale round-ups of librarians guilty of thinking for themselves. These thought criminals have been guilty of readers and loaning books like Armando Valladares’ Against All Hope: A Memoir of Life in Castro’s Gulag. Want to take a stand for gay rights? Suggest Renaldo Arenas’ Before Night Falls, which exposes the oppressive conditions faced by Cuban gays and lesbians from Castro’s homophobic regime. Unfortunately, many in the book business have turned a blind eye towards Castro’s assault on free expression. Nat Hentoff renounced his ALA Immroth Award for intellectual freedom, when the American Library Association voted down an amendment which would have protested the wholesale arrests of Cuban librarians.

If you want to hand-sell your suggestions to a bookseller, good luck. They should be receptive if they really believe in free expression. However, the Booksense and ABFFE lists clearly do not. They simply reward politically correct titles while ignoring titles literally in the line of fire from Islamic Fascism and Castro thuggery. Independent booksellers ought to start living up to their name.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Dizzy’s Night for Turner

In the 1970’s, the signature sound of jazz, was that of Creed Taylor’s CTI label. Its signature look was provided by photographer Pete Turner. Last night, Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola celebrated the launch The Color of Jazz, a collection of Turner’s fine jazz album covers.

It was a rare opportunity to hear from Taylor, who paid tribute to his photographic collaborator, before an upbeat set of tasteful swing from Patrice Rushen, playing in an acoustic trio setting, featuring Terri Lynne Carrington on drums. Rushen’s Prestige sessions were clearly influenced by the commercial success of CTI, so in a way, she was a perfect choice to help celebrate Turner and Taylor, despite not recording as a leader for the label. She has also played with label stalwarts Stanley Turrentine and Hubert Laws on sessions they cut for other labels. While most of the set consisted of her own tunes, plus a Monk standard, they did tackle Freddie Hubbard’s CTI mainstay “Red Clay.”

Taylor was best known for lushly produced sessions, featuring large ensembles. His records had a warm sound, courtesy of engineer Rudy Van Gelder, which made for romantic listening. Turner produced the perfect visuals for CTI’s gatefold covers, complementing the sounds in the grooves inside. Unfortunately, his work has not translated well down to CD-size, where it has often also been covered by additional reissue graphics. Publication of Turner’s Color of Jazz will be an excellent opportunity to see Turner’s images as they were meant to be seen.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Woodward’s Hope to Die

Hope to Die: a Memoir of Jazz and Justice

Hope to Die: a Memoir of Jazz and JusticeBy Verdi Woodward

Schaffner Press

0-97-105984-5

When reading Verdi (Woody) Woodward’s Hope to Die: a Memoir of Jazz and Justice, one can’t help wishing there was more jazz than justice in his life-story of drugs, crime, and prison. I imagine Woodward does too. The baritone saxophonist with a Belushi-like capacity to ingest narcotics tells a brutally honest life-and-death story of drug addiction—a jazzman’s A Million Little Pieces, without the exaggerations and fabrications.

Woodward started using heroin at a time when its use was widespread on the jazz scene. For many players in the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, heroin was instant cred. on the scene, and a seeming fount of creative energy. His first experience came while playing with a piano player named Joe Abrams. Woodward recalls: “I remembered throwing up all over his gray suede shoes, and also that I played forty choruses without my chops getting tired.” (p. 119)

Things quickly turned bad. Woodward would need more and more to fix, and would resort to crime to facilitate an escalating habit. Music, which had been his first connection to heroin, would suffer. When the personified gorilla on Woodward’s back taunts him, music is one of the targets:

“I always knew how to reach you; you were such an easy trick for music. But now you can’t play for shit. If you don’t believe me, check yourself out. Try playing a C major scale in tune. Try and make it sound the way it did when I was a little guy. Ah, you see, you won’t even try.” (p. 79)

Woodward takes readers on a stark tour of the early 1960’s drug scene, encompassing the streets of L.A., detouring through Mexico and the L.A. County Jail, and ending up in Folsom and San Quentin Prisons. His best period of incarceration was a brief stint in Vacaville, where drugs were easy to score and prison discipline was relatively lax. Once he had finally secured another bari, Vacaville was looking quite attractive: “I was once again just the way I wanted to be—comfortable and content with a horn in my hands and heroin in my veins.” (p. 294) Again, the contentment was not to last, as Woodward was soon transferred back to San Quentin, where he had a score to settle with the murderer of Red, his partner in a prison gambling enterprise.

Hope to Die is a gritty memoir of drugs, crime, prison, and revenge. Woodward is a forceful writer, if not always a sympathetic figure. There is no question he deserved to do his time, because he certainly did the crimes. If there is a follow-up, hopefully it will have more jazz than justice. While there may not be much of specific interest to jazz readers, Hope to Die is a cautionary tale that is also a quick and compelling read.

Labels:

Book Review,

Jazz and addiction

Monday, September 25, 2006

Steve Wiest’s Excalibur

Excalibur

The Steve Wiest Big Band

Arabesque Recordings (see special website price)

Typically, jazz looks to the future, but for his new big band project, Steve Wiest looks to the legends of yore, particularly Arthurian legend and the otherworldly fantasy of Robert Silverberg. Mixed with standards and other originals, Excalibur is a fresh big band recording from a veteran of the Maynard Ferguson band.

The title song “Excalibur” features interesting mood shifts, between a darkly martial motif and Randy Hamm’s bright, even sprightly soprano. While Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur provided inspiration for “Excalibur” the next original tune suggests T.H. White, in name at least, as “The Once and Future Groove” lays down a nice one, with Glenn Kostur’s baritone on top.

Returning to the fantasy motif, Wiest’s “A Night in Pidruid” takes inspiration directly from Robert Silverberg’s Lord Valentine’s Castle. Uniting some quirky themes to tell its story, “Pidruid” has a vaguely Mingusian feel and some fine tenor work from Ed Peterson.

Excalibur is a darkly hued affair that recast frothy old standards like “Cheek to Cheek” and “Green Dolphin Street” in very different colors than one would expect. While the assembled musicians from the Midwest may not be household names, they mesh together quite well, rising to the challenge of the demanding music. Wiest himself proves to be very articulate here, both with his trombone and his pen.

There has not been a long tradition of jazz artists drawing inspiration from fantasy literature—only Australian John Sangster’s Lord of the Rings records come to mind. Based on Excalibur, one hopes Wiest will continue to draw literary inspiration for future big band outings.

Billie Holiday on the Campaign Trail

On Friday, Republican Michael Steele used the Eubie Blake National Jazz Institute and Cultural Center as the backdrop for a “Steele Democrats” media event, earning major style points from this blog. Michael Mfume, son of former-Rep Kweisi Mfume also attended, making clear he only represented himself and not his father, quoting Lady Day:

"There is a saying by Billie Holiday. It goes: 'A mother may have. A poppa may have. But God bless a child that has its own.'"

Actually, I’m not sure “God Bless the Child” really makes sense in this context (“rich relations give crust of bread and such, you can help yourself, but don’t take too much, Momma may have . . . ") but it fits with the general Holiday vibe—that’s her on the mural under the Steele Democrats banner. Regardless, it’s still cause for major style points to Michael Mfume as well. You have to appreciate a campaign that understands the power of America’s great art form—jazz.

Steele appears to be getting it perfect, moderate enough to attract Democrat supporters, and fiscally disciplined enough to be endorsed by the Club for Growth. No wonder national Democrats are worried. (Photo from the Steele campaign website here.)

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Bluesman Concludes

Bluesman Book Three

Bluesman Book ThreeBy Rob Vollmar & Pablo Callejo

NBM/ComicsLit

1-56163-476-X

Much tragedy has come out of hope—Hope, Arkansas that it. In the graphic novel Bluesman Book Three, that tragedy is produced by Colonel Bilyeu’s lynch mob, having just murdered the brother of the Bluesman’s Creek companion, Hell-bent on extracting Bilyeu's mindless revenge on the Bluesman, Lem Taylor.

The concluding volume of Bluesman wraps things up in true Blues style, in a mounting crescendo of violence. With Bilyeu on his heels, Taylor seeks out a man in Little Rock who may have the wherewithal to help him, and also possibly offer him immortality through a recording contract. Eventually Taylor is thrown together with the legitimate lawman Sheriff Hal Beasely, who is not one to cast a blind eye on vigilante justice, in an effort to survive the lawless Bilyeu gang. Bluesman climaxes as a story of sacrifice and redemption. However, it ends on a note of real hope, becoming a love letter to those who always live in hope: record collectors.

Vollmar & Callejo convey the Southern gothic quality of the blues, which produced Robert Johnson, Peetie Wheatstraw, and the legend of Stagger Lee. The black and white art is starkly effective, and the writing demonstrates knowledge of the Arkansas music scene of the time. Bluesman Three is a strong conclusion that packs a wallop and ends on a perfect note. Along with McCulloch & Hendrix’s Stagger Lee, it is one of the best musically themed graphic novels in sometime.

Labels:

Arkansas,

Blues,

Book Review,

Graphic Novel

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Quintet to Demand End to Democracy in America

On Monday, a quintet including William Parker will demand the end of democracy in America in a concert to raise funds for the extremist World Can’t Wait organization’s efforts to “drive out” the duly and constitutionally elected Bush administration. Conveniently no mention is made of what sort of revolutionary junta would assume power, or how long martial law would be imposed.

If that sounds like an unfair characterization of World Can’t Wait, bear in mind, they proudly list Lynne Stewart as one of the “endorsers of this call” on their website. Stewart was convicted of providing material support to terrorists, namely her former client, Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman, the spiritual leader of the 1993 World Trade Center bombers. She is to be sentenced October 16. Not exactly someone who has shown commitment to civil society and the democratic system.

If Parker and his associates don’t like the Bush Administration—fine—they don’t have to. They are free to speak their minds and raise funds for the Democratic Party (or the Greens or any respectable opposition party). However, no responsible citizen would call for a coup d’etat against a democratically elected government, or align themselves with an organization endorsed by a convicted terrorist supporter. It’s time some on the left took a time out and cooled down their rhetoric.

If that sounds like an unfair characterization of World Can’t Wait, bear in mind, they proudly list Lynne Stewart as one of the “endorsers of this call” on their website. Stewart was convicted of providing material support to terrorists, namely her former client, Sheik Omar Abdel-Rahman, the spiritual leader of the 1993 World Trade Center bombers. She is to be sentenced October 16. Not exactly someone who has shown commitment to civil society and the democratic system.

If Parker and his associates don’t like the Bush Administration—fine—they don’t have to. They are free to speak their minds and raise funds for the Democratic Party (or the Greens or any respectable opposition party). However, no responsible citizen would call for a coup d’etat against a democratically elected government, or align themselves with an organization endorsed by a convicted terrorist supporter. It’s time some on the left took a time out and cooled down their rhetoric.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Banned Books for Dhimmis

With Banned Books week starting on September 23rd, many in bookselling are in full self-congratulatory mode, celebrating their “courage” for standing up to would-be censors. For instance, Booksense, the indy bookseller coalition has their picks of the top 10 banned books. They link to the nobly named American Booksellers Association for Free Expression, which has a list 100 “Banned and Challenged” titles.

Looking at the list, there is one glaring omission. Can there possibly be a more banned book than Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. For years Rushdie has lived in fear of his life due to the Iranian Fatwa that was re-upped in 2005. Verses has been banned and burned in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Somalia, Bangladesh, Sudan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Many booksellers in America were reluctant to handle it. Yet for Booksense and the ABFFE, Rushdie does not make the cut.

While Booksense’s list is exclusively fiction, ABFFE includes non-fiction as well, but was not compelled to include Oriana Fallaci’s The Force of Reason, or Melanie Phillips’ Londonistan, which certainly qualify as banned and challenged. In truth, the books on the list carry no risk in supporting. Sure, some Christian groups have objected to the occult elements of Harry Potter, but they not going to do anything besides a little protesting. Is there seriously anyone in the country worried about people buying Bruce Coville’s Skull of Truth? If so, they are not particularly organized.

Neither Booksense or ABFFE listed any books that would offend groups, namely radical Islamicists, who would act on their sense of offense. (I will however give literay and historical credit to the Booksense bookseller from Bal Harbour who successfully nominated Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We.) However, until they actually advocate on behalf of books under direct attack from Islamic Fascist elements, these bookseller coalitions will just be paying empty lip service to free expression. In truth booksellers should support free expression, loudly and vocally, because they would find many of these books they support have no place in dhimmitude.

(Disclosure: the parent company of my publishing house also owns the company which publishes Verses in tradepaper. The companies are separate corporate entities and my compensation is in no way affected by Verses sales.)

Looking at the list, there is one glaring omission. Can there possibly be a more banned book than Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. For years Rushdie has lived in fear of his life due to the Iranian Fatwa that was re-upped in 2005. Verses has been banned and burned in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Somalia, Bangladesh, Sudan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Africa. Many booksellers in America were reluctant to handle it. Yet for Booksense and the ABFFE, Rushdie does not make the cut.

While Booksense’s list is exclusively fiction, ABFFE includes non-fiction as well, but was not compelled to include Oriana Fallaci’s The Force of Reason, or Melanie Phillips’ Londonistan, which certainly qualify as banned and challenged. In truth, the books on the list carry no risk in supporting. Sure, some Christian groups have objected to the occult elements of Harry Potter, but they not going to do anything besides a little protesting. Is there seriously anyone in the country worried about people buying Bruce Coville’s Skull of Truth? If so, they are not particularly organized.

Neither Booksense or ABFFE listed any books that would offend groups, namely radical Islamicists, who would act on their sense of offense. (I will however give literay and historical credit to the Booksense bookseller from Bal Harbour who successfully nominated Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We.) However, until they actually advocate on behalf of books under direct attack from Islamic Fascist elements, these bookseller coalitions will just be paying empty lip service to free expression. In truth booksellers should support free expression, loudly and vocally, because they would find many of these books they support have no place in dhimmitude.

(Disclosure: the parent company of my publishing house also owns the company which publishes Verses in tradepaper. The companies are separate corporate entities and my compensation is in no way affected by Verses sales.)

The State of Jazz Education, More or Less

“Jazz Education—for Students Only?” was the title of the Jazz Journalists Association’s panel discuss last night. (Isn’t anyone taking jazz education courses a student?) The consensus was the state of jazz education is strong, but not really.

Evidently, there are 160 collegiate level jazz programs now accredited in America, which certainly suggests something is bubbling under the surface. Many panelists made a distinction between conservatory programs (essentially jazz musician vocational training) and liberal arts programs (history, appreciation), with a clear bias in favor of the conservatory approach. Logically, New York schools are weighted in favor of the conservatory, as so many of the leading jazz artists are living here. They have done great work, training many musicians with promising careers before them. However, I would suggest that the liberal arts programs shouldn’t be completely ignored, since they actually do more to build an audience for this important music. Disclosure: I teach a liberal arts style classes at NYU’s Continuing Education School. One of my goals in doing so is to increase the enthusiasm for jazz.

Not surprisingly, Victor Goines of Julliard and Jazz @ Lincoln Center made some of the most salient points. At one point Goines stated: “Jazz is a lot better than a lot of people really realize.” He argued that there are far more classical musicians matriculating than jazz musicians, but there are far fewer symphony jobs than jazz jobs after graduation. He also suggested jazz training was much more conducive to successful gigging in other styles (rock, pop, gospel, etc) than classical training, so the outlook for young jazz musicians is not as dire as one might think. Don’t misunderstand; he never said it was easy. Goines also made it clear why he was a teacher when he said: “We educate our students in the hope that they will be better than us.”

Other common refrains were the need to build support for jazz, and the difficulty achieving press attention. Some panelists wanted to require jazz education in elementary schools, but I think kids are resistant to mandated enlightenment. Truly, the lot of publicists, particularly jazz publicists is a hard one. Yet, off the music page PR is really what is needed. Jazz needs to get where it currently isn’t. In a way, that’s the idea of this blog. Instead of cultivating readers solely from the jazz community, I have also targeted political friends, publishing colleagues, and fellow conservative bloggers—jazz outreach of a sort.

Evidently, there are 160 collegiate level jazz programs now accredited in America, which certainly suggests something is bubbling under the surface. Many panelists made a distinction between conservatory programs (essentially jazz musician vocational training) and liberal arts programs (history, appreciation), with a clear bias in favor of the conservatory approach. Logically, New York schools are weighted in favor of the conservatory, as so many of the leading jazz artists are living here. They have done great work, training many musicians with promising careers before them. However, I would suggest that the liberal arts programs shouldn’t be completely ignored, since they actually do more to build an audience for this important music. Disclosure: I teach a liberal arts style classes at NYU’s Continuing Education School. One of my goals in doing so is to increase the enthusiasm for jazz.

Not surprisingly, Victor Goines of Julliard and Jazz @ Lincoln Center made some of the most salient points. At one point Goines stated: “Jazz is a lot better than a lot of people really realize.” He argued that there are far more classical musicians matriculating than jazz musicians, but there are far fewer symphony jobs than jazz jobs after graduation. He also suggested jazz training was much more conducive to successful gigging in other styles (rock, pop, gospel, etc) than classical training, so the outlook for young jazz musicians is not as dire as one might think. Don’t misunderstand; he never said it was easy. Goines also made it clear why he was a teacher when he said: “We educate our students in the hope that they will be better than us.”

Other common refrains were the need to build support for jazz, and the difficulty achieving press attention. Some panelists wanted to require jazz education in elementary schools, but I think kids are resistant to mandated enlightenment. Truly, the lot of publicists, particularly jazz publicists is a hard one. Yet, off the music page PR is really what is needed. Jazz needs to get where it currently isn’t. In a way, that’s the idea of this blog. Instead of cultivating readers solely from the jazz community, I have also targeted political friends, publishing colleagues, and fellow conservative bloggers—jazz outreach of a sort.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

The Sledgehammer Treatment

NY1’s Roma Torre earned her money sitting through The Culture Project’s Abu Graib inspired propaganda play, The Treatment. Her pan included phrases like:

“the execution is disappointingly heavy-handed”

“without identities, the characters fail to come to life. They are merely generic figures going through the contrived motions of trading roles as torturer and victim.”

“And both characters seem to degenerate into mouthpieces for the author as they sermonize about the new rules of war.”

“this anemically plotted work stretched so painfully thin makes 70 minutes feel awfully long.”

“Ensler’s sledgehammer treatment is numbing.”

I haven’t seen The Treatment (for the record, I’d be happy to review it with an open mind, if invited), but I’ve seen the poster (reflective of the play’s lack of subtly), so I have pretty much seen the play. Unfortunately, this is the state of Off-Broadway, with protest posters stretched into protest plays. Remember when the word “nuance” was celebrated as a fig-leaf for John Kerry’s flip-flopping? Well, nuance is out of style now. The sledgehammer approach is now in for Off-Broadway drama.

Two hours of hitting theater patrons over the head does not accomplish anything. Anyone even slightly undecided will be put off by the heavy-handed manipulation. Plays like The Treatment are not even preaching to the choir, but abusing the choir, hitting them over the head repeatedly.

Allan Buchman, the director of the Culture Project on an On Stage round table (evidently, no on-line transcript) last week sounded less interested in the events of 9-11 than the later political debates, saying: “The specific plays about 9-11 are a little less interesting to me than the effects of 9-11 on our country, and our people, and the choices our government has made.”

Nearly three thousand dead and scores of stories of heroism and sacrifice are not particularly dramatic to Buchman, but terrorist rights and the patriot act make good theater.

Actually they don’t according to Torre, at least in this case. Agit-prop theater pieces like The Treatment and Tim Robbins’ widely panned bomb at the Public Theater Embedded have been poorly received and have done nothing to advance their agendas. To be effective, political stories have to have a story that pulls you through, despite its point-of-view. A good example is The Constant Gardner, which is an extremely effective thriller, despite its anti-pharmaceutical company biases. We’re not seeing that kind of writing Off-Broadway.

At one point in the round table Buchman said: “We’re not ready to have an unbiased conversation about this [issues of terrorism and the Middle East].” That was certainly true of the On Stage panel discussion, with no voice of dissent invited to support the War on Terrorism. It was just another display of group think conformity, so common in New York right now.

One wonders what Torre and the loyal supporters of the Culture Project will have to suffer through next. A revival of Embedded perhaps?

“the execution is disappointingly heavy-handed”

“without identities, the characters fail to come to life. They are merely generic figures going through the contrived motions of trading roles as torturer and victim.”

“And both characters seem to degenerate into mouthpieces for the author as they sermonize about the new rules of war.”

“this anemically plotted work stretched so painfully thin makes 70 minutes feel awfully long.”

“Ensler’s sledgehammer treatment is numbing.”

I haven’t seen The Treatment (for the record, I’d be happy to review it with an open mind, if invited), but I’ve seen the poster (reflective of the play’s lack of subtly), so I have pretty much seen the play. Unfortunately, this is the state of Off-Broadway, with protest posters stretched into protest plays. Remember when the word “nuance” was celebrated as a fig-leaf for John Kerry’s flip-flopping? Well, nuance is out of style now. The sledgehammer approach is now in for Off-Broadway drama.

Two hours of hitting theater patrons over the head does not accomplish anything. Anyone even slightly undecided will be put off by the heavy-handed manipulation. Plays like The Treatment are not even preaching to the choir, but abusing the choir, hitting them over the head repeatedly.

Allan Buchman, the director of the Culture Project on an On Stage round table (evidently, no on-line transcript) last week sounded less interested in the events of 9-11 than the later political debates, saying: “The specific plays about 9-11 are a little less interesting to me than the effects of 9-11 on our country, and our people, and the choices our government has made.”

Nearly three thousand dead and scores of stories of heroism and sacrifice are not particularly dramatic to Buchman, but terrorist rights and the patriot act make good theater.

Actually they don’t according to Torre, at least in this case. Agit-prop theater pieces like The Treatment and Tim Robbins’ widely panned bomb at the Public Theater Embedded have been poorly received and have done nothing to advance their agendas. To be effective, political stories have to have a story that pulls you through, despite its point-of-view. A good example is The Constant Gardner, which is an extremely effective thriller, despite its anti-pharmaceutical company biases. We’re not seeing that kind of writing Off-Broadway.

At one point in the round table Buchman said: “We’re not ready to have an unbiased conversation about this [issues of terrorism and the Middle East].” That was certainly true of the On Stage panel discussion, with no voice of dissent invited to support the War on Terrorism. It was just another display of group think conformity, so common in New York right now.

One wonders what Torre and the loyal supporters of the Culture Project will have to suffer through next. A revival of Embedded perhaps?

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

City of Gabriels

City of Gabriels: The History of Jazz in St. Louis, 1895-1973

By Dennis Owsley

Foreward by Clark Terry

Reedy Press

1-933370-04-1

No player in jazz has a happier tone than St. Louis native and Ellington alum Clark Terry. In writing the forward to Dennis Owsley’s City of Gabriels the jazz legend lends his considerable imprimatur to this history of jazz in the Gateway City.

Owsley argues that St. Louis’ position as a transportation hub precluded a development of its own style, because “as a river town and railroad center, influences have come and gone. No regional style of jazz has grown up here in contrast to Kansas City or Chicago.” (p. vii) However, St. Louis can claim a privileged place as the cradle of ragtime, as adopted home of Scott Joplin and Tom Turpin. Still, through the riverboat groups of Fate Marable, St. Louis musicians took a leading role spreading jazz up and down the Mississippi.

If the St. Louis area never developed a distinct regional style, it did give the world some of the great artists in the music’s history, including Frank Trumbauer, Jimmy Blanton, Clark Terry, Oliver Nelson, and Miles Davis. At one point Owsley relates six different stories on how Duke Ellington recruited Blanton for his band, many involve Duke pulling an overcoat over pajamas as he was dragged out to a club, where he was blown away by Blanton’s bass. No matter how it happened, Blanton went on to reinvent the role of the bassist in the Ellington Band, before his life was cut tragically short.

Along with Terry, Miles Davis is one of the most celebrated Gabriels from the St. Louis area. In fact, Davis looked up to Terry as a youthful musician. Terry relates blowing off the young Davis during a performance in a park, preferring girl watching to talking music. However, shortly thereafter Terry relates climbing the stairs to a jam session, where:

I heard this horn, which I hadn’t heard before, you know. He was wailing away. And I hurriedly got to the top and walked in, and looked to see this same little timid character with legs crossed, and he was blasting away. So I said, “Hey, man aren’t you the . . .” and he said, “Yeah, I’m the guy you fluffed off in Carbondale.” And we got a big laugh about it. We often laughed about that. (p. 84)

Not all the stories in Gabriels are pleasant, particularly those involving racial segregation. As usual, the segregated white musicians’ union did little to distinguish themselves. Local 2 was the white union “mainly concerned with concert bands, symphony orchestras, and theater pit bands” and Local 44 was the African American union which “played at parties, in some cabarets, and at dances.” There was an uneasy truce until jazz, the specialty of many artists in Local 44, became the popular music of the day, which was bad news for Local 2. As Owsley relates yet another ugly chapter in labor history:

Local 2 musicians began to form jazz groups. Members of Local 2 began a systematic campaign to stop white clubs from hiring black musicians. Because gangsters owned most of the clubs during prohibition, this strategy did not succeed. With the coming of talking pictures, white musicians playing in pit orchestras began to lose their jobs. Local 2 sought ways to revoke Local 44’s charter. (p. 48)

Gabriels is an attractive oversized tradepaperback richly illustrated with photos that capture the historic periods and artists under discussion. The only drawback is that Owsley’s text sometimes gets bogged down, compulsively listing the tunes and the largely unknown personnel which played on various St. Louis sessions. Overall though, it is a handsome book that well documents jazz in the Gateway City and persuasively advocates greater support for the St. Louis jazz scene.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Willie Bobo Lost and Found

Lost and Found

By Willie Bobo

Concord Picante

If jazz has any advantage it’s the relative simplicity of producing sessions, at least when eschewing fusion-era effects and background vocals. While pop acts need extensive studio help, jazz artists do what they do best—play, which is why so much previously unreleased music has been issued from the vaults, to the general satisfaction of listeners. Thanks to Willie Bob’s son, tapes his father recorded in the 1970’s discovered in the family closet are now being released as Lost and Found, and while the tunes are a somewhat mixed bag, overall it is a very welcome addition to the Bobo discography.

Bobo was one of the most celebrated Latin percussionists, who had a tremendous influence on pop and rock. Think Santana was the first to record “Evil Ways?” Try Bobo. He would later play with Santana in Ghana during a historic concert of American music loosely categorized as Soul, which would be captured in the documentary Soul to Soul. The recordings collected on Lost come from the period following his tenure on Verve Records, which produced his biggest hits, like “Evil Ways.” Indeed several of the tracks were evidently recorded as demos for his next label.

Presumably the demo was successful, as several of these tunes were re-recorded for Bobo’s next album Do What You Want to Do. Indeed most of the tracks are quite convincing, showing Bobo at the top of his game, most notably on the up-tempo selections like “Round Trip,” with an impressive trumpet solo from someone unafraid of the upper register, and “Broasted or Fried,” with the driving drum and guitar sound that made his Verve work so successful. There’s also a kind groove going on with tracks like “Hymn to the People” (with particularly nice, relaxed alto and trumpet solos) and the darker “Soul Foo Young” that make Lost and Found a great party disc.

Some of the vocal cuts are less consistent. “Pretty Lady” works as a soulful, but forceful workout. “Dindi” and “A Little Tear” are less successful; being more in accord with what was considered “commercial” by labels at this time.

Bobo is in top form throughout, and the ensembles he used are tight and soulful too. It is a shame they are uncredited on the CD, their identities presumably lost in the sands of time. Anytime good music is discovered, it is a happy occasion. That is certainly the case with Willie Bobo’s Lost and Found.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Zorn to Dance

Writers usually break out the hyphens for John Zorn, musician-composer of jazz-klezmer-classical-hardcore punk. His music has graced the soundtracks of some very odd films, including some S&M themed features, but last night was something completely different as Zorn’s Masada songbook themes were choreographed as Masada, one of four premieres presented under the title “New Ballet Choreographers” at Columbia’s Miller Theater.

The term “world premiere” used in the program might be debatably. It seems most of the music had been previously composed and performed—just the accompanying choreography was premiering. By Saturday, the third night of performances, it would be hard to call it any kind of premiere at all. That said, the dancers were quite impressive, and actually much of the fine music would still be effective without the choreography. The Masada String Trio, who frequently collaborated with Zorn in the past, performed his music, which in this case was definitely coming out of his classically oriented bag, featuring strong Middle Eastern influences.

During the big band era, jazz was the music for dancing. Now jazz’s reign as the popular music is a distant memory, and frankly social dancing is becoming a lost art too. Jazz still finds a place in modern dance from time to time, but its unpredictability and wild abandon usually have to be tempered for the sake of the choreography. Still, there have been many examples of jazz ballets. Duke Ellington composed The River for Alvin Ailey, and Wynton Marsalis composed the music for Garth Fagan’s Griot New York (recorded as Citi Movement). Trumpeter Randy Sandke actually composed the music for The Subway Ballet, recorded by Evening Star, but has yet to be performed with choreography.

While it was not really a jazz night, it was a good show at the Miller. However, they really should fix the squeaky curtain, as it caused snickers throughout the audience as opened for the start of each performance. Perhaps the best musical performance was the Chiara String Quartet’s interpretation of Philip Glass’ String Quartet No. 5, 5th Movement.

Also of interest was Arvo Pärt’s Für Alina, the striking austerity of which often seemed at odds with the increasingly dramatic choreography. Still, it is clear why the composer often found himself at odds with the Soviet musical authorities of his native Estonia. His work, which has been recorded by ECM’s classical division, is a world away from the bombastic martial music favored by the Communists. It was nice to see some original dance at Columbia. Maybe Sandke’s agent can send one of the new choreographers a copy of The Subway Ballet for future inspiration.

The term “world premiere” used in the program might be debatably. It seems most of the music had been previously composed and performed—just the accompanying choreography was premiering. By Saturday, the third night of performances, it would be hard to call it any kind of premiere at all. That said, the dancers were quite impressive, and actually much of the fine music would still be effective without the choreography. The Masada String Trio, who frequently collaborated with Zorn in the past, performed his music, which in this case was definitely coming out of his classically oriented bag, featuring strong Middle Eastern influences.

During the big band era, jazz was the music for dancing. Now jazz’s reign as the popular music is a distant memory, and frankly social dancing is becoming a lost art too. Jazz still finds a place in modern dance from time to time, but its unpredictability and wild abandon usually have to be tempered for the sake of the choreography. Still, there have been many examples of jazz ballets. Duke Ellington composed The River for Alvin Ailey, and Wynton Marsalis composed the music for Garth Fagan’s Griot New York (recorded as Citi Movement). Trumpeter Randy Sandke actually composed the music for The Subway Ballet, recorded by Evening Star, but has yet to be performed with choreography.

While it was not really a jazz night, it was a good show at the Miller. However, they really should fix the squeaky curtain, as it caused snickers throughout the audience as opened for the start of each performance. Perhaps the best musical performance was the Chiara String Quartet’s interpretation of Philip Glass’ String Quartet No. 5, 5th Movement.

Also of interest was Arvo Pärt’s Für Alina, the striking austerity of which often seemed at odds with the increasingly dramatic choreography. Still, it is clear why the composer often found himself at odds with the Soviet musical authorities of his native Estonia. His work, which has been recorded by ECM’s classical division, is a world away from the bombastic martial music favored by the Communists. It was nice to see some original dance at Columbia. Maybe Sandke’s agent can send one of the new choreographers a copy of The Subway Ballet for future inspiration.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Playing the Word

Playing the Word

Mike Melvoin Presents Dan Jaffe

City Lights

Poetic interest in music is understandable. After all, poetry has identifiably musical elements, particularly its use of rhythm. As the Beats starting improvising with their poetry, they would logically be drawn to improvisational music, namely jazz. However, many resulting collaborations between poets and jazz artists have been uneven, with the music usually relegated to providing whimsical accents to poet’s recitation. Mike Melvoin and Dan Jaffe’s Playing the Word is more successful because both artists’ voices are prominently featured.

Unlike some jazz and poetry sessions where the poet or reciting artist bellows over a blaring ensemble, Playing the Word is a simple, stripped down session—just voice and piano. Structurally, it resembles an intimate torch song performance, in which Melvoin takes legitimate jazz solos, in between the vocal passages, and Dan Jaffe’s reciting has a restrained speak-on-the-beat quality that often approximates that of a jazz vocalist. They mesh together quite well, as can be strikingly heard in their interplay on the Latin flavored “Cajon/GoJazz,” one of the CD’s highlights.

Jaffe’s poetry speaks of jazz directly, often cueing Melvoin as in “It Sure is Risky and Afterwards” when around the 5:50 mark the melody of Ellington’s “Satin Doll” dovetails into Jaffe’s passage:

With women it’s called waiting

First you wait to see if she was listening

When you played “Satin Doll”

Then to say if she meant that smile for you.

While many jazz greats are celebrated, first among equals is Charlie Parker, whose life and music are reoccurring touchstones throughout Word, on tracks like “Blowing,” “High Flyers,” and the twelve and a half minute “Bird Talk,” an extended tribute presenting dramatic vignettes from Parker’s life, like:

Doctor told me something profound

He said “Bird, you can’t mess up your body forever

You’re stuck in that sack of bones

and it will tell you when it won’t carry you around no more”

I said “Doctor of medicine, learned you may be

I’m going to beat the destiny you’re bound to

I’m going to fly out of here with my soul together.”

Indeed, the longer tracks are the best, as they allow Melvoin more time to stretch out on his solos. Melvoin demonstrates a light swinging touch, and tremendous flexibility accompanying Jaffe. Melvoin has been criminally underappreciated throughout his career as a pianist, perhaps due to the studio work he did on behalf of more popish acts like the Four Freshmen (although he did produce a groovy take of “Everyday People” for them). It’s great to hear him play in an intimate setting. His recent trio outing You Know is another fine showcase for Melvoin’s tasteful piano. While most jazz & poetry sessions do not reward repeated listening, Playing the Word holds up far better because its overall effect more closely resembles that of a traditional vocal session.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Ginger Baker in Africa

Ginger Baker in Africa

Directed by Tony Palmer

53 minutes

Eagle Rock Entertainment

Given the success of Drumstruck! Off-Broadway, it seems odd that there has yet to be a cast album. However, Ginger Baker in Africa newly on DVD, features excellent African percussion that might appeal to the same audience. For others, the footage of Fela Kuti relatively early in his career alone will be worth the price of admission.

Like Andy Summers of The Police and Charlie Watts of The Rolling Stones (whom Baker succeeded in Blues Incorporated), Ginger Baker is a musician who initially found fame through a rock group, but recorded jazz sessions later in his career. In the period after Cream, before leading groups with Bill Frisell and Ron Miles, Baker explored African music. In 1971, Tony Palmer documented Baker’s trek from Algeria to Nigeria, across the Sahara desert.

The result is a trippy road movie with a great soundtrack, which is most definitely of its time. Despite the heat which literally melted the tires of his Range Rover, Baker keeps his shaggy red hair and beard throughout his journey. It was an eventful trip, complicated by an expensive run-in with the gendarmerie in Tamanrassett, related in an animated sequence (presumably the constabulary put the kibosh on the cameras).

Even with the sand constantly in his cameras, Palmer produced some attractive looking sequences, particularly Baker’s arrival in Lagos. Of course for most, Fela Kuti & Africa ‘70 performing at Calabar will be the highlight.

As an example of a rock oriented, jazz influenced musician interacting with African artists, Ginger Baker in Africa might make for a good double feature with Soul to Soul. Regardless, the combination of the music, Palmer’s visuals, and Baker’s laconic narration make Ginger Baker in Africa entertaining viewing.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Giants of Jazz

Giants of Jazz

By Studs Terkel

The New Press

1-5684-999-X

Now in tradepaperback

Like a Broadway revival, Studs Terkel’s Giants of Jazz, might be familiar to many, but its republication in tradepaper will be greeted as a welcome return. Terkel profiles thirteen true giants of American music. Though not exhaustive by any means, his sketches convey a good sense of the artists under discussion.

Using plain English Terkel effectively describes the complicated styles and complicated lives of his subjects. Of Charlie Parker he writes: “It has been said that Bird played the same songs but never, never, the same solos. That made it difficult, if not impossible for others to copy him, though he had scores of imitators.” (p. 171)

When describing Coltrane’s music, which so often defied words, Terkel nicely captures the essence of Trane’s art:“As he sailed up and down scales, playing individual notes, trying to sound them rapidly enough to make them simulate complete chords, he brought yet another dimension to the music called jazz.” (p. 175)

While much biographical detail has been left out, Terkel chooses fitting career highlights, as when he highlights Dizzy Gillespie’s role as a cultural ambassador on behalf of the U.S. State Department during the Cold War. Most observers agreed with Terkel’s assessment:

Dizzy Gillespie was a wonderful ambassador of goodwill. He and his music won over these people immediately.

“I have never seen these people let themselves go like this,” observed an American official at Damascus. He himself had been suspicious of jazz. (p. 165)

Throughout Giants of Jazz, Terkel writes with lightly elegiac touch, as many of his subjects had already exited the stage at the time of his writing. With line illustrations and French flaps, it is an attractive volume that will look good in anyone’s collection. When one actually reads Giants, Terkel’s knowledge and affection for those who create and perform jazz comes through crystal clear.

9-11: the Human Cost for the Jazz Community

The human suffering caused by murderous Islamic Fascist terrorists on September 11th can be overwhelming to contemplate. Yet some in the creative community, such as Matthew Shipp in Jazz Times' 9-11 commemorative issue, discount the tremendous human tragedy of 9-11. Lest we forget, 9-11 took a tremendous toll on the jazz community.

Most important to remember, the jazz community lost one of its own in that cowardly act of terror. Betty Farmer, a jazz vocalist working for Cantor Fitzgerald was killed that day. She started her singing career in the cradle of jazz, her hometown New Orleans, and performed with Duke Ellington. According to the New York Times’ “Portrait of Grief,” she was in the process of re-launching her performing career.

The jazz community also suffered severe economic losses as a result of 9-11. Wendy Oxenhorn of the Jazz Foundation often speaks eloquently about the number of gigs that either dried up completely, or went from paid gigs to pass-the-hat gigs. People were much less likely to go out in the immediate aftermath of 9-11, which took a severe economic toll on jazz venues. Charles Lloyd played a free stand at the Blue Note in an effort to encourage patrons to return to the clubs. Make no mistake, creative artists—particularly jazz musicians, were attacked on September 11, 2001. Therefore, we all have a stake in fighting Islamic extremists terrorists, wherever they may hide.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Ronald E. Magnuson

According to the New York Times’ “Portraits of Grief,” Ronald Magnuson was an avid golfer, who shot a hole-in-one, a feat few golfers can reasonably hope to accomplish, roughly twelve years before he lost his life on September 11th. His success on the links is telling, as golf is a social sport. Strangers are often thrown together is twosomes or foursomes, to cooperatively navigate the course, while competing with each other.

Indeed, the Times reports Mr. Magnuson, a contractor with Cantor Fitzgerald, “raised his children—Sheryl, 20, and Jeff, 23—to love conversation as much as he did. His idea of a great night out was a rousing talk over a restaurant dinner, with any or all members of his family.” A portrait emerges of a man beloved by family and friends, respected by neighbors and colleagues, mourned by all who knew him.

We should all mourn the loss of Ronald Magnuson and all who were murdered on September 11th. While we do not feel the loss as acutely as their family and friends, we have all been denied the future opportunity to be enriched by nearly three thousand individuals, as colleagues, friends, neighbors, and friendly golfing competitors.

On this anniversary I hope Mr. Magnuson’s family and friends find a measure of comfort and solace.

(Read more tributes to those who lost their lives on 9-11 at the 2,996 Project site. Mirror site here.)

NY1 Group Think

If you thought NY1’s panel discussion on civil liberties post-9/11 was one-sided, you do not want to see their forum on the response of the arts, which aired Friday night. There is possibly no more perfect example of group think than the panel assembled for the program. David Friend of Vanity Fair, John Hoffman of HBO Documentaries, Oskar Eustis of the Public Theater, and Catharine Stimpson of NYU spoke with one collective voice. Of the four, Hoffman was came off as the most moderate and least political, but tipped his ideological hand with praise for the documentaries of Michael Moore and Spike Lee. Eustis primarily used the forum as a platform to criticize the Bush administration and the War to liberate Iraq. Friend and Stimpson were happy to echo Eustis.

In response to a question, Stimpson was particularly vehement denouncing ABC’s The Path to 9-11, disparaging her perception of the producer’s decision “to use the occasion—the search for truth, pretend you’re searching for truth, and then give it a really vicious political spin.” Someone who studies media should know the issue of historical accuracy in docudramas is hardly new. Unless she was equally vociferous in condemning Oliver Stone’s JFK and CBS’ The Reagans, she is now being disingenuous.

The truth is there was relatively little discussion of the arts at all, particularly artistic responses to 9-11. Hoffman discussed the making of HBO’s In Memoriam: September 11, 2001 in some detail during his opening segment. Again, The Path to 9-11 was dutifully criticized, and Oliver Stone was actually taken to task for not addressing the root causes of terrorism in World Trade Center. Aside from that, Anne Nelson’s The Guys, Neil LaBute’s The Mercy Seat were featured in the opening video, and were briefly mentioned later by Eustis, but very few actual works of art, film, or theater discussed. United 93 for instance, never passed the lips of the panelists, and musicians who responded to 9-11 (like jazz artists Geri Allen and Charles Lloyd) were entirely ignored. The participants were more interested in scoring points against the administration.

Surely NY1 could have found at least one right of center panelist knowledgeable in the arts to participate, if they had simply contacted The New Criterion. They preferred to present an exercise in group think. I constantly hear people in New York say dissent is patriotic. There was not a hint of dissent from anyone on the lockstep panel, making NY1’s presentation most unpatriotic by New York standards.

In response to a question, Stimpson was particularly vehement denouncing ABC’s The Path to 9-11, disparaging her perception of the producer’s decision “to use the occasion—the search for truth, pretend you’re searching for truth, and then give it a really vicious political spin.” Someone who studies media should know the issue of historical accuracy in docudramas is hardly new. Unless she was equally vociferous in condemning Oliver Stone’s JFK and CBS’ The Reagans, she is now being disingenuous.

The truth is there was relatively little discussion of the arts at all, particularly artistic responses to 9-11. Hoffman discussed the making of HBO’s In Memoriam: September 11, 2001 in some detail during his opening segment. Again, The Path to 9-11 was dutifully criticized, and Oliver Stone was actually taken to task for not addressing the root causes of terrorism in World Trade Center. Aside from that, Anne Nelson’s The Guys, Neil LaBute’s The Mercy Seat were featured in the opening video, and were briefly mentioned later by Eustis, but very few actual works of art, film, or theater discussed. United 93 for instance, never passed the lips of the panelists, and musicians who responded to 9-11 (like jazz artists Geri Allen and Charles Lloyd) were entirely ignored. The participants were more interested in scoring points against the administration.

Surely NY1 could have found at least one right of center panelist knowledgeable in the arts to participate, if they had simply contacted The New Criterion. They preferred to present an exercise in group think. I constantly hear people in New York say dissent is patriotic. There was not a hint of dissent from anyone on the lockstep panel, making NY1’s presentation most unpatriotic by New York standards.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Publishing Jumps on the Bandwagon, Attacks the Path to 9-11

If a major publisher pulled promotional materials for fear of offending conservative bloggers, Publisher’s Weekly (book publishing’s trade journal) could be counted on for outraged cries of censorship. Today, PW Daily celebrates Scholastic for replacing a viewer’s guide for The Path to 9-11, with in their words: “an alternative guide that, appropriately (if ironically), deals with issues of media literacy.” PW's recap of the controversy essential boils down the DNC’s talking points:

“While ABC was taking a drubbing in the blogosphere for its upcoming miniseries about the events leading up to September 11, Scholastic was apparently hard at work recasting its association with the docudrama. After The Path to 9/11 generated an outcry from liberal bloggers and then, yesterday, Bill Clinton publicly condemned the series for historical inaccuracies—the crux of the left wing's anger stems from fictional scenes that lay blame for the attacks on the Clinton's administration.”

PW declined to mention any of positive reviews generated by the other side of the blogosphere, letting the controversial contentions of wholesale inaccuracies stand as established truth. Instead PW characterizes the reaction as monolithically negative. Unfortunately, I never saw the offending viewers’ guide before Scholastic yanked late last night (good news: Riehl World has it here). Its replacement is clearly intended to undermine the credibility of Path to 9-11, with leading discussion points like:

"What are the matters of dispute in the docudrama? What are the scenes that were altered or did not happen? How do these scenes affect your understanding? Are the changes part of an effort by the producers to shape your beliefs about these events? In your view, is this an appropriate way to treat an event such as this?"

This is my industry, ever loyal to Bill Clinton, willing to attack any who question his legacy. This is par for the course for PW, but remember Scholastic’s actions here when you’re about to plunk down $30 for the next Harry Potter. Better yet, wait for the mass market.

“While ABC was taking a drubbing in the blogosphere for its upcoming miniseries about the events leading up to September 11, Scholastic was apparently hard at work recasting its association with the docudrama. After The Path to 9/11 generated an outcry from liberal bloggers and then, yesterday, Bill Clinton publicly condemned the series for historical inaccuracies—the crux of the left wing's anger stems from fictional scenes that lay blame for the attacks on the Clinton's administration.”

PW declined to mention any of positive reviews generated by the other side of the blogosphere, letting the controversial contentions of wholesale inaccuracies stand as established truth. Instead PW characterizes the reaction as monolithically negative. Unfortunately, I never saw the offending viewers’ guide before Scholastic yanked late last night (good news: Riehl World has it here). Its replacement is clearly intended to undermine the credibility of Path to 9-11, with leading discussion points like:

"What are the matters of dispute in the docudrama? What are the scenes that were altered or did not happen? How do these scenes affect your understanding? Are the changes part of an effort by the producers to shape your beliefs about these events? In your view, is this an appropriate way to treat an event such as this?"

This is my industry, ever loyal to Bill Clinton, willing to attack any who question his legacy. This is par for the course for PW, but remember Scholastic’s actions here when you’re about to plunk down $30 for the next Harry Potter. Better yet, wait for the mass market.

NY1-sided 9-11 Forum

Casting aside any pretense of impartiality, NY1 (Time Warner’s local NYC news channel) last night presented a forum on the trade-off between security and civil liberties after September 11th, which clearly tilted the playing field in favor of those opposed to aggressive anti-terror measures. Of the four panelists, two were explicitly opposed to the Bush administration’s homeland security initiatives. One was Norman Siegel, formerly of the NYACLU, and perennial candidate for public advocate (a useless elected office in New York City). The other was Mohammad Razvi of the Council of Peoples Organization, evidently an advocacy group for illegal aliens from the Middle East whom federal authorities have sought for questioning. There were no advocates of the Bush Administration’s policies per se, or conservatives of any stripe to be heard from. Richard Aborn of Citizen’s Crime Commission, a consultant to urban police forces, and Richard Pildes of NYU Law, were generally sympathetic to law enforcement, but straddled a mushy middle on policy questions, showing no desire to counterbalance the more partisan panelists. As one would expect, Siegel and Razvi were allowed to dominate the terms of the debate.

NY1 most vividly tipped their hand in the flagrantly biased wording of their so-called snap poll questions. The first was:

“Since September 11, my civil liberties have been challenged:

A. Too much

B. Not enough

C. The right amount”

The clear premise of the question is that current counter-terror policies represent a challenge to civil liberties—a leading question if ever there was. How to answer it if you don’t believe civil liberties have been meaningfully challenged? Much to host Budd Mishkin’s undisguised shock, B was the winner with 43 percent, despite attempts to lead poll voters. (On-line voting after the broadcast has brought the results more in line with NY1 presumed result. You can vote here yourself.) The second question was:

“In this post-9/11 world, which of the following concerns you the most?

A. Extra searches

B. Privacy issues

C. Racial profiling”

Evidently, being killed in a terrorist attack was not considered a “concern” by NY1.

An honest debate can be had on the balancing act between security and civil liberties. However, NY1 did not provide one. Instead they presented an obviously stacked deck that played to a partisan crowd, rather than elevating discourse.

NY1 most vividly tipped their hand in the flagrantly biased wording of their so-called snap poll questions. The first was:

“Since September 11, my civil liberties have been challenged:

A. Too much

B. Not enough

C. The right amount”

The clear premise of the question is that current counter-terror policies represent a challenge to civil liberties—a leading question if ever there was. How to answer it if you don’t believe civil liberties have been meaningfully challenged? Much to host Budd Mishkin’s undisguised shock, B was the winner with 43 percent, despite attempts to lead poll voters. (On-line voting after the broadcast has brought the results more in line with NY1 presumed result. You can vote here yourself.) The second question was:

“In this post-9/11 world, which of the following concerns you the most?

A. Extra searches

B. Privacy issues

C. Racial profiling”

Evidently, being killed in a terrorist attack was not considered a “concern” by NY1.

An honest debate can be had on the balancing act between security and civil liberties. However, NY1 did not provide one. Instead they presented an obviously stacked deck that played to a partisan crowd, rather than elevating discourse.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

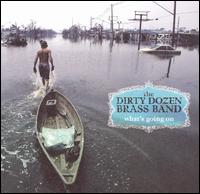

Dirty Dozen Brass Band Going On

What’s Going On

The Dirty Dozen Brass Band

Shout! Factory

Few concept albums have had the enduring impact of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. In the wake of Katrina the Dirty Dozen Brass Band found fresh meaning in Gaye’s songs, reinterpreting the complete album. There is some precedent for jazz artists covering entire albums. Don Randi actually reinterpreted two Beatles albums, Revolver and Rubber Soul. Arguably jazz renditions of Hair by Barney Kessel and Stan Kenton among others fit into this tradition. The Dirty Dozen Brass Band may not perfectly fit into a jazz bag having led the revitalization of New Orleans marching bands, infusing the traditional brass band sound with funk and r&b elements. Now their rendition of What’s Going On will help revitalize the New Orleans music scene, with a portion of the proceeds going the Tipitina’s Foundation’s artist relief efforts.

Things kick off with the title track, opening with a sample from Fearless Leader Ray Nagin, leading into Chuck D’s rap, with predictably simplistic “No Child Left Behind” political lyrics. While What’s Going On was definitely a protest song, the rap here lacks the soulfulness of the original. Bettye LaVette is much more successful conjuring a Marvin Gaye vibe on “What’s Happening Brother” and Ivan Neville turns in the most soulful vocal on “God is Love,” with sanctified organ/keyboards setting the groove.

In fact, What’s Going On is best when the Dirty Dozen does what they do best on the instrumental tracks. On “Flyin’ High (in the Friendly Sky)” Kevin Harris’ tenor and Gregory Davis’ trumpet are as expressive as any vocalist could be. “Right On” featuring the low-down funk of Revert Andrews’ trombone and Roger Lewis’ baritone is the kind of fare longtime Dirty Dozen fans will eat up. The sanctified mood returns on “Wholly Holy” through Kirk Joseph’s sousaphone and the trombone of Revert Andrews.

Brass bands were not just alive and well in New Orleans before Katrina. They were vital, creatively evolving ensembles, with substantial local and national followings. The Dirty Dozen’s What’s Going On reminds us of the energy of that scene, and gives some hope it has not been washed away in the flood.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Stagger Lee

Stagger Lee

Stagger LeeBy Derek McCulloch & Shepherd Hendrix

Image Comics

1-58240-607-3

Stagger Lee, a.k.a. Stackalee et al, is the original anti-hero of American blues, immortalized in various renditions by the likes of Furry Lewis, Lonecat Fuller, Duke Ellington, Professor Longhair, Taj Mahal, and Fats Domino. McCulloch & Hendrix’s graphic novel Stagger Lee dramatizes the historic Lee “Stag Lee” Shelton, while analyzing various incarnations of the Stagger Lee songs during interludes from the narrative. While each version changes elements of the events on that fateful Christmas Eve night, as McCulloch summarizes: “There’s one point, though, on which all parties seem to agree. Stagger Lee shot Billy.” (p. 7)

Lee Shelton really did shoot Billy Lyons. Whether it was a dispute over a Stetson hat, or a matter of self-defense is a point of contention in McCulloch’s story. However, the underlying conflict was political. Lyons was part of an influential Republican family, while Shelton was part of an emerging urban Democrat party machine, though he starts his pay-per-vote career reluctantly, saying: “my momma whip me she ever heard I voted for them Democrats. She say Mr. Lincoln be turnin’ in his grave.” (p. 70)

Shelton’s political connections provided for the best available defense attorney, Nathan Dryden, the first prosecutor to secure the conviction of white man for the murder of a black man. He was also a morphine addict. Such is the stuff the blues were made of.

Dryden argued his way to a hung jury for Shelton, but died before his second trial. As witness stories changed it became increasingly unclear whether Shelton killed Lyons out of self-defense. Eventually, Shelton would be convicted and did time in prison before a Democrat governor commuted his sentence.

The musical interludes are entertaining and informative, as when they illustrate Ma Rainey’s “Stack O’Lee Blues,” which conflates Stagger Lee and “Frankie and Johnny.” It was a natural fit since “Only five years later and about a dozen blocks away from where Lee Shelton shot Billy Lyons, Frankie Baker finally decided that her man, Allen “Albert” Britt . . . had done her wrong.” (p. 85) Incidentally “Duncan and Brady” are also cleverly worked into the narrative. Hendrix’s art, almost entirely black and white line drawing, conveys an effective film noir atmosphere, which serves the story well.

Stagger Lee is a thoughtful graphic novel deeply steeped in the blues, which should also appeal to readers of period crime fiction like the Alienist. It also has contemporary resonance, as it depicts the corrupt workings of the nascent St. Louis Democrat machine, led by “Colonel” Ed Butler, particularly relevant in light of recent political corruption cases from the St. Louis/East St. Louis area. Party enforcer Kelvin Ellis could argue his conviction for vote buying and indictment for conspiring to kill a federal witness simply follows in the tradition of Stagger Lee.

Stagger Lee remains the archetype of the “bad man” of blues legend. McCulloch & Hendrix's excellent Stagger Lee paints as complete a portrait possible of the man, without ruining the aura of mystery which surrounds his legend.

Labels:

Blues,

Book Review,

Graphic Novel,

St. Louis,

Stagger Lee

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Hester’s Bigotry and Afrocentric “Jazz” Evolution

Bigotry and Afrocentric “Jazz” Evolution

By Karlton E. Hester, Ph.D.

Global Academic Publishing

1-58684-228-5

In jazz, one is expected to develop their personal style. Each recording should reflect the leader’s style. When writing about jazz, one can expect individual’s particular point of view to inform their writing and give it distinction. However, a specific point of view should not create blind spots of bias, for the sake of an agenda. Too often, Hester’s Bigotry and Afrocentric “Jazz” Evolution falls into that trap.

Hester is strongest when he concentrates on two areas, illustrating the roots of jazz in African musical styles, and in giving just due to underappreciated jazz figures. In discussing the role of the bass in jazz, Hester illuminates an under sung figure in Bill Johnson. As Hester writes: “The man who introduced the style involving pizzicato articulation on the “jazz” bass was Bill Johnson. He played with power, used triplets, and his bass lines were steeped in syncopation.” (p. 159)

In some respects, Hester echoes the concerns of Stanley Crouch, insisting that the African-American roots of jazz not be minimized or obscured. Given the role of such creators as Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, such arguments are on solid ground. It is when Hester addresses white jazz artists, that his racial politics complicate matters. It becomes somewhat ugly when he repeatedly belittles Bill Evans. In his introduction, Hester castigates Gene Lees for supposedly “bigoted comments” advocating a high place for Evans in the Pantheon of jazz innovators, which Hester claims “would never be taken seriously among African-American innovators.” (p. xxxviii) When profiling the great piano stylists in jazz history, the best Hester can grudgingly muster for Evans is a terse and dismissive paragraph. Hester writes:

“Evans often omitted certain chord tones, especially the root, and expanded his chord voicing by adding extensions of ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths to provide more transparent textures. His musical style was vaguely reminiscent of Debussy’s turn-of-the-century Impressionism. Such harmonic extensions were introduced and exhaustively explored by earlier pianists such as Tatum and some bebop innovators. Yet, Evans’s approach reflected a more restrained European sensibility.” (p. 192)