These Naval aviators are quite surprised to be training at an Airforce facility.

My late father, a former Naval aviator, might be turning over in his grave at

the very suggestion. This flight of Navy officers is particularly uncomfortable

there, because they happen to be the Navy’s team of women air-show

demonstration pilots. However, desperate times call for unorthodox measures and

a North Korea-like rogue state’s nuclear testing absolutely qualifies as a

crisis in Ashley L. Gibson’s Called to Duty, which releases tomorrow on

VOD.

The

“Wing Girls” are inspired by the WWII Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs),

but they are Navy instead of Air Force. Even though they are fulltime

active-duty, they are only supposed to make exhibition flights and not perform

combat operations. That is how their leader, Kaden “Country” Riebach reconciles

her service with her Christian faith. She really takes the “thou shalt not kill”

part seriously.

Serving

with cocky male pilots like Jeter “Ego” Ulter really tests her Christian charity.

Say what you will, but Ego has one of the most believable call signs of any

military aviation movie. He is also a jerk and Margo “Edge” Lee is not about to

let his sexist cracks slide. In fact, she is always spoiling for a fight. Yet,

the Wing Girls, Ulter, and several top Airforce pilots will have to work

together to pull off a strike on “North Kiyoung’s” nuclear program. There are a

lot of misgivings regarding the Wing Girls’ involvement, including from Country,

but the DOD is convinced they are only pilots agile enough to evade the North

Kiyoung anti-air defenses.

Between

its feminism and some characters’ Evangelical Christianity, there is something

in Called to Duty to alienate either side of the social spectrum—which we

should respect it for. Gibson and screenwriter Bobby Hammel never make things

too easy for the Wing Girls. Arguably, the messiness of their climactic mission

is much more realistic than the Top Gun films. However, it totally

sacrifices authenticity with the frequency with which major characters

disregard orders. That just doesn’t fly in any branch of the service. (In

contrast, the “S.O.S.” episode of Quantum Leap did a good job

establishing the significance of chain-of-command in military service.)

Despite

these credibility issues, Called to Duty is refreshingly patriotic. It

is no accident it is releasing right before the 4th of July.

Clearly, the filmmakers had a lot of sympathy for military personnel and their

families. Nevertheless, it is pretty weak of Hammel to create aliases for North

Korea, China, and Cuba. The truth is most of the potential audience for Called

to Duty would love to see a successful mission against any of those three terrorist-sponsoring

countries, so why not give it to us?

This rescue mission should not have been necessary. Biden’s withdrawal from

Afghanistan was strategically questionable, but the execution was a humiliating

horror show. The chaos also caught Zoe Walters’ missionary father by surprise

too. However, the U.S, military was so grateful for his help during the

evacuation, they redirect Master Chief Richard Mirko’s team to extract him and

his family. Sadly, little Zoe will be the only one left to save and Mirko is

the only surviving team-member who can save her in Johnny Strong & William

Kaufman’s Warhorse One, which opens this Friday in theaters.

Mirko’s

team were on their way to another mission when they reassigned to save the

Walters instead. Unfortunately, the team’s chopper is blown out of the sky, leaving

Mirko the only survivor. He wants to take the fight to the Taliban in the area,

but Commander Johns back at HQ keeps him on mission. Tragically, the same

Taliban faction also found the Walters’ transport. Only Zoe survived, because her

mother died shielding her.

Initially,

Zoe is also frightened of Mirko when he finds her. However, she starts to trust

him, because she recognizes the wounded sensitivity under his gruffness. When

you boil it down, Warhorse One is a lot like Man on Fire,

transplanted to the mountains of Afghanistan. Of course, that means each time

Mirko guns down a Taliban fanatic (and he blasts a lot of them), viewers get

some cathartic endorphins.

Frankly,

you have to give credit to Strong, who plays Mirko and co-wrote and co-directed

with Kaufman, because Warhorse One has enough slam-bang action to hang

with Extraction 2. The body count is impressive, but its depiction of

boots-on-the-ground warfighting is grounded in reality.

Hopefully, there are better safeguards in place for real-life air travel, but regardless, Idris Elba and the rest of the cast still elevate the "real time" thriller HIJACK. EPOCH TIMES exclusive review up here.

Cardinal Joseph Zen could use the unique sort of help Father Lorenzo Quart

provides, but unfortunately, the current Pope let him stand trial on bogus “national

security” charges without a single word of protest. Sadly, the Church has lost

its moral authority under Francis. While Quart often feels morally conflicted,

he always maintains the righteous path. That is not easy to do when you serve

as the Vatican’s armed troubleshooter. His latest case is a political

minefield. As one might anticipate, the intrigue soon leads to danger in Sergio

Dow’s The Man from Rome, adapted from Arturo Perez-Reverte’s novel The

Seville Communion, which releases this Friday on-demand and in theaters.

Two

dead bodies have been found in the wealthy Bruner’s family’s traditional church.

Perhaps they were accidents, but a mysterious hacker brought it to the Pope’s

personal attention by hacking his laptop. The Seville diocese wants to sell the

property to a dodgy developer, but Macarena Bruner is trying to exercise her

contested rights to block the sale, as ambiguously negotiated when her family

donated the land to the Church centuries ago. She also happens to be trying to

divorce the developer in question. There are a lot of old grudges in play,

including the Cardinal of Seville, whose reputation was tarnished during one of

Quart’s previous investigations into Church mismanagement.

Quart’s

inquiry will be fair and unbiased, but his values and personality are clearly

much more compatible with those the future Duquesa Bruner, and her sly mother,

the current Duquesa. However, there will be no monkey business, because Quart

is serious about his vows, despite his frequent differences with Vatican

policies. The truth is Quart was much more conflicted in Perez-Reverte’s novel.

Readers might remember a telling passage in which Quart debates whether to wear

a tie to meet Bruner at a fancy restaurant, but reverts back to his collar at

the last minute. That kind of ambivalence regarding his calling is missing from

Dow’s film.

Yet,

Man from Rome is still one of the better Perez-Reverte adaptations.

Roman Polanski swung for the fences and struck out when he adapted The Club

Dumas as The Ninth Gate. Dow and his battery of contributing writers

stripped down the source novel to a lean procedural (maybe too lean) and they

maintain the deliciously ironic final revelation. Frankly, most viewers will

not see it coming, because of their junk-culture conditioning.

It is sort of like A Simple Plan, but in Pittsburgh instead of rural

Minnesota. It turns out that is a more dangerous place to squabble over

misplaced drug money, considering how freely the Russian mob operates there.

Joe Washington’s dad worked as a mule for the “Thieves by Law,” until his

accidental death, but not before he stole 10 million dollars and a Lamborghini

we have yet to see. Not surprisingly, the Russian mob wants it all back in

creator Robb Cullen’s Average Joe, which is now streaming on BET Plus.

Washington

and his friends are struggling to get by. His wife Angela should see a

specialist and his daughter Jennifer will need college tuition. Leon

Montgomery’s hardware store is barely scraping by, while their friend Benjamin

“Touch” Tuchawuski, a white desk-cop, as they frequently point out, is wracked

with guilt over a family tragedy. Nobody would have thought Washington’s dad

had ten million bucks laying around, so he is quite surprised when the Russian

gangsters start asking for it, in a rather rude manner.

Quite

awkwardly, one of them happens to be Dimitri Dzhugashvili, his daughter’s

boyfriend. Frankly, Washington never really liked him, even before

Dzhugashvili’s goon started breaking his fingers. However, ten million would

solve a lot of problems. They would solve a lot of problems for Montgomery and

Tuchawuski too, who also get involved. Despite their clueless reluctance,

Washington’s family and Montgomery’s true crime-binging wife Cathy soon also get

mired in their scheme.

Based

on the first two episodes, Average Joe is surprisingly funny, in a

one-darned-thing-after-another kind of way, especially the second episode,

which really leans into the morbid humor. Cullen and the writing team have

already buried Washington in a host of troubles worthy of an average Job. They

also have a decent handle on how the Thieves By Law operate. Generally

speaking, it is not a good idea to cross them.

Umberto Eco became an international bestseller with a mystery about a poisoned

book. Yet, probably nobody better loved the look and touch of the printed page,

especially those in ancient volumes, than he did. Despite knowing better, he

rarely used gloves while perusing the rare, centuries-old tomes in his 50,000-volume

collection. David Ferrario takes viewers into the Eco library, to examine the

philosophical ideas and eccentric academic fascinations of the late great

writer in Umberto Eco: A Library of the World.

Obviously,

Eco was not an internet kind of guy. He likens it to the information overload

that plagues that hapless central character of Jorge Luis Borges’ “Funes the Memorious,”

who was driven mad by his ability to remember every single little detail of his

life, no matter how trivial. It does rather make sense Eco was a Borges kind of

guy, even though the Argentine fantasist was not writing in the 17th

Century.

Ferrario

is particularly interested in Eco’s pessimistic view on the long-term epistemological

impact of the internet. To over-simplify matters, he did see a potential for it

to make people dumber rather than smarter. He spoke of three types of memory: the

organic stored in brains, the vegetal stored on wood and paper, and the mineral

stored in silicon. He rather liked the vegetal version.

Eco

also had a passion for Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit who wrote richly

detailed studies of the natural sciences that were almost entirely wrong. Yet,

the systemic logic of his “alternate science” fascinated Eco. It is easy to see

the influence of Kircher’s hermetic world view and the rare occult and alchemy books

Eco also collected in his novels. Weirdly though, Ferrario spends very little

on Eco’s fiction and almost none on the conspiratorial Foucault’s Pendulum,

which seems like his most relevant novel for our current times.

Each

section of Ferrario’s library culminates in an Eco monologue recited by one of

the author’s admirers, in a suitably cinematic library setting. The selections

emphasize Eco as an epistemologist. Each reflects his talent for language, but

several boil down to rather pithy arguments that a bibliophile affix to their

fridge with a cat magnet. However, the writer’s literary fans will learn a good

deal about Eco the family man, through warmly engaging interviews with his

widow, daughter, son, grandson, and protégé.

How many times must the citizens of Iran take to the streets to protest

their oppressive clerical regime, before the governments of the liberal West

finally do something tangible to support them? Sadly, we are still asking. Who

in the Biden administration could object to the most recent Iranian protest

slogan: “women, life, freedom?” It is indeed Iranian women who were at the

forefront of the latest round of protests and it has been Iranian women who

have been dying as a result. Drawing on a wealth of protest footage posted (at

least temporarily) to social media and authenticated by third parties, Nightline

documents the demonstrations and the regime’s brutal response in director Majed

Neisi’s “Inside the Iranian Uprising,” which premieres on digital this Thursday.

It

all started with the murder Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a Kurdish Iranian woman, who

died in a Tehran hospital, after having been arrested by the Iranian Morality

Police. Her story went viral throughout Iran and around the world, after

reporters (one of whom, Niloofar Hamedi, has since been arrested) published

photos of Amini in a coma and her parents grieving in the hospital.

Many

women were so outraged, they took to the streets, burning their hijabs in public

protests, even though that very definitely made them targets for the same savagery

that killed Amini. One of those was Nika Shakarami, a 16-year-old YouTube

influencer, who mysteriously disappeared after burning her hijab in a protest,

until the government finally produced her body nine days later, claiming she

was the victim of a highly convenient suicide.

Yet,

some of the most horrific accounts of torture in this Frontline report

come from men, like the medical student who bravely offers an on-camera description

of how he was sodomized with a police baton. Neisi and the Frontline producers

mask the identity of another torture victim, using a British voice actor to

overdub his shocking account of how the so-called Morality Police raped him and

another man while they were in custody.

The Securitas cash depot heist remains the UK’s largest cash robbery in

history. Showtime took that one on with the multi-part doc Catching Lightning.

The Brinks-Mat heist was the largest gold score. If you own British jewelry

crafted after the 1983 robbery, it is thought you most likely have some of the

boosted bullion mixed into your bling. Obviously, it was a high-profile crime,

but the investigation broke somewhat new ground pursuing those who fenced,

smelted, laundered, and invested the illegal fruits of the crime. The

investigation and pursuit of the guilty parties are solid grist for creator-writer

Neil Forsyth’s six-part true crime drama The Gold, produced by the BBC,

which premieres tomorrow on Paramount Plus.

Brian

Boyce was a legend at Scotland Yard for his service in Northern Ireland.

Initially, leading the Brinks-Mat special task force looks and feels like a

demotion, but he soon realizes the case might encompass some of the corrupt

elements within the Metropolitan Police he has long resented. Nicki Jennings

and Tony Brightwell are not part of that clique, which is why Boyce keeps the “Flying

Squad” members on the case.

Stumbling

upon the bullion was a happy surprise for Micky McAvoy and his accomplices, but

they were not prepared to move it. Fortunately, he knew Kenneth Noye and John

Palmer, dodgy gold dealers with a long history of criminal associations, who developed

a method to smelt off the serial numbers and create a fraudulent paper trail,

to sell the gold back into the market.

Noye

also has a few semi-secret allies. He happens to be a Freemason, as is Neville

Carter, a highly placed cop in Metropolitan HQ. Thanks to their uniformed

brothers, Noye has been able to operate with impunity throughout his career.

Carter is also a link to fellow freemason Edwyn Cooper, a social-climbing

lawyer, who married into an impeccable establishment family. Cooper will set up

the shell companies, the Swiss accounts, and the real estate investments, but

he will never directly touch any of the cash.

Everyone

should be insulated from everything except their own link in the chain, which

makes the case particularly frustrating for Boyce’s honest cops to investigate,

especially with the UK’s minimal early 1980s bank reporting regulations. That

makes the step-by-step detective work to reveal the conspiracy so fascinating.

However,

that Freemasonry business is no joke. At one point Boyce literally calls the Freemasons

within the Metropolitan force the “hidden hand.” It all sounds very weird,

almost like the Birchers discussing the Council on Foreign Relations. Yet,

apparently, this somewhat resonates in the UK. In the late 1990s, Labour Home

Secretary led a movement to force Freemasons to disclose their membership

before when up for judicial or police appointments.

Despite

the conspiratorial tone, the procedural elements are highly compelling.

Regardless of who belonged to what lodge, the major developments of the case

largely follow the historical record, including all the criminal trials depicted.

Their audience could use a good laugh, but they are forbidden to clap. In

1942, the Femina Theatre in the Warsaw Ghetto did indeed open a door-slamming musical

farce written by Jerzy Jurandot. On the surface, it would seem to have little

relevance to lives of its audience and cast. However, as the characters

on-stage shift partners, the participants in a backstage love triangle wrestle with some life-and-death questions, as

well as whom they plan to face them with in Rodrigo Cortes’s Love Gets a Room,

which releases today in theaters and on-demand.

Stefcia

is a survivor, as we see from the way she navigates the ghetto in the opening

sequence, helping others to survive grim encounters with their German captors,

on her way to the theaters. The play is Jerzy Jurandot’s Love Gets a Room,

which would explain the film’s seemingly inapt title. Rather awkwardly, Stefcia

stars as the newlywed wife of her torch-carrying ex-lover Patrik, while

co-starring with her current lover Edmund, who plays the husband of her friend

Ada.

In

the play-within-the-play, both couples are assigned the same apartment by the

Ghetto’s Jewish Council, so they decide to make the best of it and live

together. Of course, during the course of the stage play, the four newlyweds

inevitably start to fall in love with their opposite’s mates. Behind the

scenes, Patrik reveals he has bribed a National Socialist officer to allow him

to escape. He wants Stefcia to come with him, even though he knows she no

longer loves him. Somewhat to her annoyance, Edmund wants her to agree, because

it is clear by this point what will happen to those who remain in the Ghetto.

Apparently,

most of the film unfolds in real-time during the performance of Jurandot’s

play, which was reconstructed for Cortes’s film. The text and lyrics all

survived, but new era-appropriate music was composed by Victor Reyes. However,

their performance is not entirely faithful. As the intrigue grows backstage,

cues are missed, requiring some rather raggedy improvisation.

Yet,

that is all part of the intelligence of Cortes’ screenplay and his success

realizing it on-screen. Cortes has been off-the-radar since the disappointment

of Red Lights, but Love Gets a Room represents a significant creative

comeback. The parallels between on-stage and backstage are cleverly executed

and the long tracking shots give the film a sense of dramatic tension akin to

live stage performance.

Say what you will about the French, but back in the day, they certainly had

a flair for public executions. The ominous sight of the guillotine blade slowly

going up and quickly coming down really made an impression. Thesp-turned-director

Ida Lupino capitalized on that inherent drama in one of the nine episodes she

directed for the classic Boris Karloff-hosted anthology series Thriller.

A convicted murderer hatches a plan to cheat the blade, but irony might still

kill him in “Guillotine,” which screens Saturday at UCLA.

This

episode of Thriller will be presented as part of a sort of triple-crown

of macabre anthology episodes helmed by Lupino. Some of us might rank Outer

Limits above Alfred Hitchcock Presents¸ but nobody will argue with The

Twilight Zone and real fans will defend Thriller to our dying

breaths. “Guillotine” is from the second season, so we no longer get the

catch-phrase: “As sure as my name is Boris Karloff, this is a thriller.” However,

this episode introduces the guest stars as severed heads falling into a basket.

It is a crude super-imposed video trick by today’s standard, but the spirit is

still delightfully ghoulish.

Robert

Lamont was sentenced to death for murdering his wife Babette’s lover, which

makes her feel rather guilty. Evidently, if the executioner, a.k.a. Monsieur de

Paris, the “headman,” blows off the appointment, or dies himself before a successor

is announced, the accused walks free—sort of like when the rope broke in the Old

West gallows. Therefore, Lamont asks his wife to repeat her infidelity, to keep

his head attached. If she can’t keep him in bed, then she should put him into

the ground.

Film

Noir was definitely Lupino’s forte, as you can see from this stylish episode.

Even though it is not supernatural in nature (unlike some episodes), her dark

visual sensibilities give this historical Thriller an almost gothic feel.

If the Hollywood industrial complex will stealth-censor The French Connection, how long will it be before they remove the “problematic” parts

from Midnight Cowboy? Don’t immediately dismiss the notion. After all, Popeye

Doyle’s censored racist comments were intended as the opposite of an

endorsement—and the French Connection won more Oscar’s than John

Schlesinger’s X-rated best picture winner. Instead of pondering this question,

Nancy Buirski’s interview subjects spend a lot of time talking about the Vietnam

war and the cultural climate of the late 1960s in the awkwardly titled Desperate

Souls, Dark City and the Legend of Midnight Cowboy (it is also missing a serial

comma), which opens tomorrow in New York.

According

to the talking heads, the era of Midnight Cowboy was the best of times

and the worst of times. The film faithfully captured the gritty, sleazy desperation

of New York City when it was literally teetering on the brink of financial

collapse. Yet, it was greenlighted at a time when the studios were giving talented

young filmmakers virtual carte blanche, provided they work within reasonable

budget constraints.

It

was also a time when major studio films were including increasing explicit

sexual content. Midnight Cowboy was also one of the first films to

depict homosexuality, in dangerous underground encounters that make Jon Voigt’s

Joe Buck character freak out in rather homophobic ways. Apparently, this was

all made possible by the Vietnam protest movement, which Desperate Souls etc.

etc. discusses almost as much as Schlesinger’s film. It also clearly

pre-supposes the audience only shares the New Left’s perspective, showing no

affinity for the experiences of veterans, their families, or the Vietnamese

boat people, who desperately fled for their lives after the fall of Saigon.

Perhaps

more “problematic” is the uncritical discussion of screenwriter Waldo Salt’s

blacklisting during the McCarthy Era. The Blacklist was an ugly practice, yet we

know with certainty from the Venona decryptions, the CPUSA (which Salt had joined)

worked hand-and-glove with the KGB and NKVD. Are you happy Putin has threatened

Ukraine with nuclear weapons? Then thank former CPUSA party members, like Harry

Gold and Julius Rosenberg, who revealed the secrets of the atom bomb to Stalin.

Frankly,

the only interesting sequences in Desperate Souls are Jon Voigt’s

interview segments discussing his involvement with the counter-culture at the

time, given his current standing as Hollywood’s most outspoken Trump supporter.

You could say he always was a rebel.

This portal fantasy world keeps bankers’ hours: nine to five, Japanese time.

To get there, seven troubled middle-schoolers literally travel through the

looking glass. What they find is more like a clubhouse than Narnia, but its

rules still need to be respected in Keiichi Hara’s Lonely Castle in the Mirror,

from GKIDS, which screens today and tomorrow nationwide.

Kokoro

has almost entirely stopped attending school, after the bullying she faced

drastically intensified, but she is too ashamed to explain it to her parents. Just

when she really sinks into depression, “Ms. Wolf” pulls Kokoro through her

mirror to a remote, fantastical castle, entirely surrounded by water, where six

other confused middle schoolers are waiting.

They

will have the run of the place until one of them finds a magic wish-granting

key. Once they wish for their heart’s desire, all seven will lose their

memories of the strange castle and of each other. Until then, they can spend as

much time there as they like, as long as they leave by five. If they are caught

after hours, they will be eaten by “the Wolf.”

Slowly,

the seven become friends and discover the secrets they have in common. There

always seem to be exceptions to their conclusions, but there are always good reasons

for them. It is not entirely unfair to think of Lonely Castle as a Breakfast

Club portal fantasy, but there is more to it than that. For one thing, it

riffs on Little Red Riding Hood (Ms. Wolf sometimes even refers to the

seven misfits as her “Riding Hoods”), much in the same way Belle riffed

on Beauty & the Beast.

Cycling's greatest showpiece event has lost seven years of its history. With that

in mind, Greg LeMond’s final 1990 Tour de France victory does not seem quite as

long ago. That was the last time an American won the Tour, fair and square. However,

LeMond’s 1989 Tour de France was more dramatic and more hard-fought. Alex

Holmes chronicles LeMond’s career, placing special focus on the 1989 Tour de

France in the documentary, The Last Rider, which opens this Friday in

New York.

Greg

LeMond was the great American cycling hope, at a time when most Americans

hardly spared a thought for the sport. The young cyclist’s talent was so

evident, he was recruited for the legendary Bernard Hinault’s team. After

helping Hinault win his fifth Tour de France, LeMond was promised 1986 would be

his turn. However, he was betrayed by his team, his coach, and his mentor. John

Dower’s excellent documentary Slaying the Badger covered that race stage-by-stage,

whereas Holmes gives the broad strokes, saving the fine detail for the 1989

Tour. In between, LeMond suffered a life-threatening hunting accident that

temporarily shattered his body and his confidence.

Nobody

expected LeMond to be in contention when he returned to the Tour de France in

1989. Most of the attention was on Pedro Delgado (one of the film’s other

primary talking heads) and Laurent Fignon, who died in 2010. Each rider had his

highs and lows. However, Fignon’s nasty behavior in the media does not exactly

burnish his reputation.

Holmes

previously featured Greg LeMond and his wife Kathy at great length in Lance Armstrong: Stop at Nothing, an expose of Armstrong’s criminal enterprise

and his attempts to smear critics, like the LeMonds. Holmes’s two cycling docs

and Dower’s film together provide a comprehensive portrait of LeMond. However,

each film individually fully establishes the cyclist as a sympathetic underdog

champion, of tremendous resilience and integrity. Obviously, he is a much more

worthy role model than Armstrong ever was.

Mo Washington is part “Little Joe” Monahan (who was the inspiration for the

Suzy Amis western, The Ballad of Little Jo) and part Mary Fields, the

legendary black old west mail-carrier, who also famously toted a shotgun.

Washington has passed for a man since she enlisted in the Buffalo Soldiers. She

has ambitions to settle down and build a community, but killing keeps following

her in Anthony Mandler’s Surrounded, which releases tomorrow on VOD.

Washington

has a gold claim and a dream, but every step of her journey to Colorado is

fraught with peril. New Mexico will be where the sagebrush really hits the fan.

Despite having a ticket, the racist shotgun-rider forces her to sit on back

jump seat of the coach. Wheeler, a lawman passenger, is maybe a little

sympathetic to “him,” as he assumes her to be, but only so to an extent.

Nevertheless,

when the notorious Tommy Walsh Gang attacks the coach, Wheeler is happy to have

Washington’s steady Remington on his side. With her help, they overcome the

bandits and capture Walsh, but at a high cost. The coach is lost and perhaps

Washington’s dreams with it. Bizarrely, Wheeler leaves Washington to guard

Walsh, because holding a gun on a white guy, even bandit like Walsh, is such a

comfortable place for him (her) to be in 1870 New Mexico. However, Walsh can

see her for who she is. Thus begins a long night of verbal sparring.

Despite

the High Plains Drifter-style hat, Letitia Wright cannot

convincingly pass for a guy. Yet, weirdly, Surrounded makes that a virtue,

emphasizing how “unseen” Washington moves through life. Walsh’s marginal status

gives him a small degree of understanding, which makes his temptations and

mind-games very effective drama.

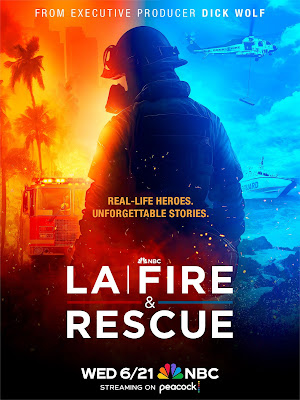

Los Angeles is an unusually hard city for firefighters. The climate is dry,

the winds frequently shift, and crime is sky-high. Station 16 in Watts

typically responds to very different calls than Station 37 in Palmdale,

surrounding by highly combustible desert brush. However, every station keeps

incredibly busy. At least that provides a lot of material for the new reality

series LA Fire & Rescue, co-executive produced by Dick Wolf, which

premieres this Wednesday on NBC.

The

format is recognizable. It is basically Cops, without cops. Of course,

the firefighters work closely with the LAPD and Sheriff’s Department, but the

series does its best to minimize the presence of lawmen. In this case, viewers

also see a little bit of the firefighters’ personal lives and personalities.

Captain Dan Olivas maybe gets the most screentime in the first three episodes

(provided for review), because of the way he enjoys joshing with his station-mates

at the 16—and getting joshed right back. It is also largely the same at home,

with his big, loving family, including a grown son currently at the fire

academy.

Throughout

the first two episodes, viewers see how rampant crime makes their jobs so much more

difficult. In the opener, “Best Job in the World,” Station 16 responds to a gas

station fire, where a car involved in a high-speed police chase took out a live

gas pump. Then, in the second episode, “Three Alarm,” the same station must

tend to a man suffering head trauma resulting from a random attack with a lead

pipe.

Station

16 certainly gets plenty of work, but Station 41 in Compton out-paces them for

title of LA’s busiest station. That is why they have never been assigned a “boot”

(probationary officer still completing training), until now. On her first

shift, she responded to twenty-six calls. Fortunately, she has a conscientious mentor

in Captain Scott Woods.

Watching

LA Fire & Rescue certainly gives viewers a renewed appreciation for

first responders. Usually, there is one major emergency teased throughout the

show, supplemented by several serious, but less potentially catastrophic (from

a civic perspective) calls to illustrate the department’s everyday life saving

work.

The crime drama is decent, but Adrian Dunbar's jazzyish crooning is quite impressive in PBS's RIDLEY. EPOCH TIMES review up here.

Switzerland has gone fascist. Maybe it was funded by some of those Swiss accounts

looted during WWII, the last time the Swiss were showing some fascist tendencies.

Cheese is the instrument of control for President (for life) Meili. It makes

the Swiss people docile and stupid. Consumption is mandatory and lactose intolerance

has been criminalized. However, Meili’s storm-troopers pick the wrong mountain

lass to mess with in Johannes Hartmann & (“co-director”) Sandro Klopfstein’s

Mad Heidi, which has a special nationwide Fathom Events screening this

coming Wednesday.

It

is still relatively peaceful up in the Swiss Alps, where the orphaned Heidi

lives with her grandfather Alpohl, a former revolutionary, when she isn’t rolling

in the hayloft with Goat Peter, a (not so lonely) goatherd and underground

fromager. Unfortunately, there will be no mercy when Kommandant Knorr busts

Goat Peter for illegal cheese trafficking. After his summary execution, she is

sent to a women’s prison clearly inspired by nazisploitation movies, such as Ilsa,

She-Wolf of the SS.

Being

behind bars with predatory body-building women will make Heidi stronger, instead

of breaking her. However, she will need help from the spirits of Helvetian warriors

to reach her full battle potential.

If

you believe Troma represents the pinnacle of cinematic accomplishment than Mad

Heidi will be your kind of movie. Yet, the truth is: it is a little too

much like Hobo with a Shotgun. The gory mayhem is often more

mean-spirited than humorous. It is the sort of mash-up than requires the ambience

of a rowdy late-night theater audience to distract from its shortcomings (and

the relentless cruelty it depicts). It certainly makes sense for Fathom to

screen it as a special one-off, which is the only way anyone should consider

seeing it.

Apparently, if you want to kill Tyler Rake, you must drop him in a vat of molten steel,

like Robert Patrick in T2. When we last saw Rake in the first film, he fell

off a very large bridge in Bangladesh after getting riddled with bullets.

However, the film established he could hold his breath under water for a very

long time, so there’s that. Regardless, Rake is still alive, so best of luck to

all the bad guys who try to kill him in Sam Hargrave’s Extraction 2,

which premieres today on Netflix.

At

least #2 acknowledges things really looked bad for Rake. As a result, he spends

weeks in a coma before undergoing months of rehab. His merc boss Nik Khan just

wants him to quietly retire so he can work on all the emotional issues that fueled

his near-death wish, but that won’t be happening.

Instead,

he agrees to rescue his estranged ex-wife’s sister, young niece, and annoying pre-teen

nephew from the heckhole Georgian Republic prison, where they are forced to

live with the druglord brother-in-law. Clearly, Davit Radiani still has the

juice to demand such accommodations, despite being convicted of murdering an

American DEA agent. Understandably, being incarnated with the abusive Radiani

is slowly killing Ketevan and her children, but the worshipful Sandro is too

brainwashed to see his father’s true nature, or that of his psychotic uncle

Zurab. Regardless, Rake will bust them out anyway, whether Sandro likes it or

not, with the reluctant help and considerable logistical support provided by

Khan and her younger brother Yaz.

The

first Extraction, also helmed by Hargrove and written by the Russo

Brothers and graphic novelist Andre Parks, had plenty of action and considerable

body-count, but #2 surpasses it in all ways. As fans would expect, Chris

Hemsworth’s Rake is still quite a one-man killing machine.

However,

the big news is how Iranian exile Golshifteh Farahani really comes into her own

as a breakout action star. Khan was also part of the climactic shoot-out in #1,

but she possibly caps as many bad guys in #2 as Rake does. She is in the thick

of it, right from the start, but it is not to make any stilted statement. Khan

and Rake are really partners in the on-screen action (technically, he works for

her, but you get the point).

That

said, Hemsworth still anchors the most brutal hand-to-hand beatdown, as Rake

escorts Ketevan through a full-on prison riot, which even overshadows the

complicated escape sequence it bleeds into, involving cars, helicopters, and a

speeding train. #2 features an extended 21-minute long-take, but viewers will

not really notice the technique, because the stunt work is so intense.

According to traditional Korean beliefs, it is best to keep newborn babies and

their parents sequestered for the first twenty-one days, to prevent

contamination from evil spirits and taboo-related bad vibes. If that sounds

ridiculous, try arguing the point from the 13th floor of a New York high-rise

built within the last twenty years. Obviously, we humor some superstitions in

the West. Woo-jin takes the same approach towards his wife Hae-min and her

super-superstitious mother. However, when he attends his ex’s funeral against Hae-min’s

wishes, he brings home something sinister in Park Kang’s Seire, which

releases today on VOD.

Woo-jin

is rather surprised to find himself here. One year prior, he broke up with his

long-term girlfriend Se-young, because of rather profoundly differing relationship

goals. Yet, after marrying Hae-min (rather quickly), here Woo-jin is—a new

father. Then he gets a text announcing Se-young’s funeral.

Hae-min

urgently argues against Woo-jin attending, but he feels dutybound to go. Much

to his surprise, Se-young has, or rather had, a perfectly identical twin,

Ye-young. It is incredibly awkward, for reasons that are largely his fault.

When he gets home, strange things start happening. First their fruit takes a

rotten turn. Soon, Hae-min insists Woo-jin engage in drastic folk remedies, but

he is distracted by a suspicious chance encounter with Ye-young.

As

horror films go, the slow burn of Seire is particularly slow, but the

burn scorches deeply. This is an incredibly dark and moody film, because Park’s

execution is unusually accomplished, especially for a feature debut. Credit should

also go to Hwang Gyeong-hyeon’s forebodingly atmospheric cinematography.

Movies based on comedy sketches have a pretty spotty track-record. Remember films

like It’s Pat and Night at the Roxbury? The trend continues. The

misses out-number the hits in this slasher satire, but the shortage of kills really

undermines the genre cred of Tim Story’s The Blackening, which opens

tomorrow in theaters.

There

is a cabin in the woods and there is an evil game, like Uncanny Annie, Game of Death, Ouija, Beyond the Gates, or whatever. The twist is this sinister

board game has a blatantly racist theme. If you do not play you die. If you do

play, you probably still die, but at least you play for some time. It did not

work out so well in the prologue for Morgan and Shawn, the organizers of this

weekend reunion for their old college friends. At first, they were psyched to

see their Airbnb had a game room, but then the “Blackening” game sealed their

fate.

Of

course, they are nowhere to be found when the rest of the guests show up.

Nevertheless, they all pick right back up where they left off, playing the same

drinking games and busting the same chops. However, they are surprised to learn

the strait-laced Clifton was also invited. They never really liked him, so when

the game calls for a scapegoat, he is the one they chose.

It

is not like they really wanted to play. Unfortunately, the unseen host has

remote control over all the doors and windows. The Jigsaw-like figure is also holding

one of their friends, so they really do not have much choice. Yet, for horror (ostensibly), the

ultimate survival rate is bizarrely high.

Frankly,

The Blackening is not nearly as clever as it thinks it is. It wants the

respect of The Menu or Us, but it is written at a level that is

barely a step above the Scary Movie franchise. By far, the film’s best elements

are the character of Clifton and Jermaine Fowler’s portrayal of the unexpected

guest, both of which are so sharp, they largely subvert screenwriters Tracy

Oliver and Dewayne Perkins’ exhaustingly didactic messaging.

Thrillers about women escaping abusive relationships with men are often pitched

with the term “toxic masculinity.” There will be no toxicity applied to this

film, but poor Billie would probably be safer dating Archie Bunker than her

current girlfriend, Alex. She has a bad feeling terrible things have happened

in her life since they met, but she cannot put her finger on anything specific,

beyond a few fragmentary visions in Kelley Kali’s Jagged Mind, which premieres

today on Hulu.

Viewers

will see Billie meet Alex in a bar, several times, for the first time.

Evidently, she has a family history of neurological problems that cause cognitive

issues, so she already had cause for medical concern. Unfortunately, Billie is

starting to blackout and experience time in a non-linear fashion. Alex is

determined to take care of her, but she also deliberately isolates Billie from

her friends and support network.

Kali

and screenwriter Allyson Morgan make it clear from the start that Alex is big,

big trouble, but keep the secrets of what she is doing and how reasonably shrouded

until the third act. Jagged Mind is either a light horror movie or a

very dark thriller with fantastical elements, but it is different and

surprisingly effective. It is also a rare film that explores the darkside of Haitian

magic, without digging up any zombies.

Billie’s

breakdowns and disjointed perception of reality are critically important,

because they offer clues to her situation and build the tension. Fortunately,

Kali realizes them quite adroitly. In fact, they are sufficiently sinister to

tilt the film into horror territory for a lot of viewers.

Anyone who happens to be named “Maggie Moore” will probably get some ribbing

over this film during the next few days. Fortunately for them, it will then be

largely forgotten. In the movie, two unfortunate women with that name happen to

get murdered days apart. Like viewers, Police Chief Jordan Sanders believes it

is too coincidental to be a coincidence in John Slattery’s Maggie Moore(s),

which releases this Friday in theaters and on VOD.

The

first Maggie Moore we see die is actually Maggie Moore #2, in the awkward and unnecessary

in media res prologue, before Slattery shows us Maggie Moore #1. She had the

great misfortune to discover her husband Jay has unknowingly traded manila

envelopes full of explicit under-age sexual material to Tommy T, in exchange

for expired food to serve at his failing sub shop (maybe “Jared from Subway” is

a customer). Right off the bat, you might have an inkling Slattery and

screenwriter Paul Bernbaum have trouble finding the right vibe for their extremely

dark material.

Even

though Jay Moore apparently did not know what he was passing along, Maggie Moore

#1 still understandably freaks, so Tommy T puts him in touch with Kosco, a deaf

hired thug, to “handle” her. To Jay M’s partial “surprise,” he handles her

permanently. Through a mildly odd chain of events, the newly widowed Moore

happens to know there is another Maggie Moore in town, which gets him thinking.

That will mean more work for Sanders, but at least this case introduces him to

Maggie Moore #1’s next-door-neighbor, Rita Grace. She is a nosy divorcee. He is

a sensitive widower. They could be perfect together, if neither of them

sabotages it—but that’s unlikely.

Maggie

Moore(s) (just

try writing a review of this film without accidentally calling it Maggie

May(s), six or eight times) could have been a slyly amusing film, but

Bernbaum needed ten or twelve further drafts to iron out all the kinks. Instead,

this film will leave viewers baffled, with a severe case of whiplash from the

tonal shifts. One minute, it is a genial rom-com about middle-aged misfits

taking a second chance at love. Then, suddenly, innocent people are getting

viciously murdered over packets of illegal pornography.

Few writers have been ripped-off as much as Agatha Christie. Seriously, how

many And then There Were None clones have you seen? With that in mind, who

could blame the Christie estate for cutting some licensing deals that are rather

distantly related to her printed words? Swedish television developed a series

based on Sven Hjerson, the meta creation of Hercule Poirot’s occasional companion,

mystery writer Ariadne Oliver. Similarly, French TV has very loosely adapted

some of Christie’s mysteries, with completely original characters in the ongoing

series Agatha Christie’s Criminal Games. After seasons set in the 1930s

and 1960s, the mysteries shift to the “Me Decade” when the ten-episode Agatha

Christie’s Criminal Games: The 1970’s premieres today on MHz Choice.

In

some ways, Captain Annie Greco is a feminist trailblazer, but she is also a

tough cop, freshly assigned to city of Lille. Most of her insubordinate subordinate

detectives are both sexist and incompetent, but Max Baretta has promise. His

deductive instincts are not bad, but he has been banished to file room, because

of his anger management issues.

Greco

assigns Baretta as her partner, but his career resuscitation will come at a

price. He must attend sessions with Rose Bellecour, the extremely fashionable

psychologist they meet on their first case. Thanks to her parents’ cosmetic

company, Bellecour has become the confidant of actress Anna Miller, whose

co-star (and abusive ex) has just been murdered.

As

the only episode of the season largely “inspired” by a particular Christie

novel, Endless Night, it is not surprising the like-titled episode is

one of the most successful of the 1970’s. It also has one of the best

guest-starring turns from Romane Portail as Miller. Those who prefer to watch

rather than read Dame Agatha might know the 1972 film with Britt Eklund and

George Sanders. If so, they can surely guess the killer, but that means Flore

Kosinetz and Helene Lombard rather faithfully adapted it for Criminal Games.

The

other episodes, which are almost wholly original, are more hit or miss. However,

it is worth noting “The Mice will Play” incorporates elements of The

Mousetrap, with a mystery that

hinges on an unwanted baby given up years prior. Poor Baretta also has a rare

chance for healthy romance with Flore, an up-scale” “hospitality worker,”

nicely played by Aude Legastelois.

Unfortunately, the bickering cats-and-dogs

chemistry between Arthur Dupont and Chloe Chaudoye as Baretta and Bellecour gets

very tiresome. Emillie Gavois-Kahn wears much better on viewers’ nerves over

time as the no-nonsense Greco. However, her supposed obliviousness to the

romantic interests of Jacques Blum, the coroner, also starts to wear thin. Furthermore,

the hippy-dippiness of her new residence, the Nirvana Hotel, really gets

shticky.

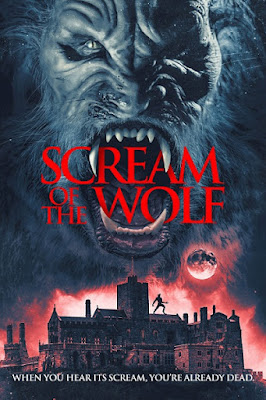

This film crew has made a horrible mistake with their props. They thought

they were filming a vampire movie, so they are well-equipped with wooden

stakes, but they will be stalked by a werewolf instead. As horror specialists,

they should be able to pivot quickly, but their bickering and disorganization makes

them easy prey in Dominic Brunt’s amusing werewolf comedy Scream of the Wolf,

which releases tomorrow on VOD and DVD.

The

shoot is almost over, but the alcoholic star, Oliver Lawrence, would hardly

know it. He looks a lot like fellow vampire thesp Jonathan Frid, but his

drunken eruptions into Shakespeare soliloquys also suggest a good bit of John

Carradine too. Fiona the 1st A.D. somewhat indulges him, because she

is a fan—at least she was—but she and Derek, the director, constantly scramble

to keep him away from the bottle. Two “journalists” from a horror magazine are

expected for a set-visit, but they will not arrive in one piece. Instead, the

crew stumbles over their severed limbs and a dying corpse.

Frankly,

none of them should have been there. The production was supposed to vacate the

rented manor before the full moon. Of course, the slimy producer wanted had to

stretch out the shoot, to accommodate the publicity event. That kind of shameless,

self-centered Hollywood-wannabe behavior constantly makes the situation worse

for everyone.

You

can tell from the opening credits Brunt and screenwriters Joel Ferrari and Pete

Wild love a lot of the Hammer and Universal monster movies that you and I do.

Admittedly, it starts a little slow, but the werewolf design is pretty cool.

There is also a terrific extended stinger that explains the origin of the wolf.

James

Fleet (from Bridgerton and Four Weddings and a Funeral) is very

amusing as the hammy, drunken Lawrence. Fans will see a lot of their favorites

in him, especially the aforementioned Carradine. Frankly, Fleet outshines just

about everyone, but Stephen Mapes is also spectacularly sleazy as Peter, the

dirtbag producer.

The picturesque Austrian village of Altaussee probably boasts the only

working mine that also features an art exhibit. There is a good reason for

that. During WWII, the salt mine served as the secret hiding place for art

looted by the National Socialist regime. You might remember scenes of its liberation

in George Clooney’s The Monuments Men. Screenwriter-director tells the

story from the perspective of the miners in Secret of the Mountain,

which premieres Tuesday on MHz Choice.

Sepp

Rottenbacher keeps himself to himself, but not his childhood friend, Franz

Mittenjager, who is widely known to supply food to the band of deserters encamped

in the mountains. That secret is a little too open for his own safety, but his

equally rebellious wife Leni would not have it any other way. Slowly but

surely, the villagers are also becoming more defiant, as they receive news of

the Axis’s military defeats.

The

mines might not seem like a good place to store art, but the temperature and

humidity in the deeper shafts were almost perfect. Their depth also provided

protection from Allied bombing runs. Unfortunately, Hitler decided to destroy

the Altaussee mine and all the art stored within, as part of his scorched earth

strategy. Blowing up the art would also obliterate the village’s primary source

of employment. Of course, the fanatical National Socialists do not care, but the

catastrophic prospect finally shakes Rottenbacher out of his apathy.

Even

though Secret in the Mountain was produced for Austrian television, but

it is a high-quality period production, with some surprisingly sophisticated

characterization. Unlike many “reluctant heroes,” who cannot hardly wait for

their awakening of conscience, Rottenbacher’s change of heart is a bitter,

hard-fought process. Likewise, the miners’ “courtship” of SS Officer Ernst

Kaltenbrunner to countermand the Altaussee’s standing orders for destruction gives

the film an ironic twist. However, it is worth noting Zerhau’s screenplay

largely lets the mining village off the hook for collaboration, while

short-changing the efforts of the American Monuments Men to secure the

imperiled art beneath Altaussee.

Considering the Soviets repurposed concentration camps into gulags after WWII, it is

hardly surprising East Germany found new uses for an uncompleted Nazi resort on

the Baltic Sea. The nearly three-mile eight-building complex never had an

explicitly military purpose while Hitler was in power, but the ideology guiding

its construction and its subsequent use during the socialist regime make its

current mixed-use (hotels, luxury condos, and a youth hostel) quite

controversial. Mat Rappaport explores the structures’ history and significance

in the documentary, Touristic Intents, which opens Monday in LA.

The

“Colossus of Prora” was supposed to host up to 20,000 loyal vacationing Germans

in equal egalitarian comfort. It was conceived by the National Socialist labor

organization Strength Through Joy as a place where working-class German union

members could vacation like the privileged bourgeoisie. It was never completely

finished, but it served as temporary barracks for concentration camp support staff

during the war. Although it would not have had high strategic value, it

arguably still would have been a legitimate military target, had the Allies

known of it.

Throughout

the post-war years, the GDR regime put Prora to a variety of uses. Most

notoriously, it became a camp for the conscientious objectors the Protestant Church

had pressured the Communist state into excluding from armed service. One of the

survivors, Stephan Schack, explains how the state systematically attempted to

break him and his fellow dissenting conscripts while they were essentially

imprisoned in Prora.

The

best segments of Touristic Intents are those featuring Schack—by a

country mile. The rest of the on-camera commentators lack his emotional

resonance, but they are also quite reserved and mostly rather dull. Many of

them are also largely in denial. Frankly, Strength Through Joy perfectly

illustrates the socialism in National Socialism. It was literally a massive

social welfare public works project spearheaded by a quasi-governmental union. Nevertheless,

many talking heads argue it Strength Through Joy wasn’t really a union, because

its dues were so high. And yet, so many people felt compelled to join.

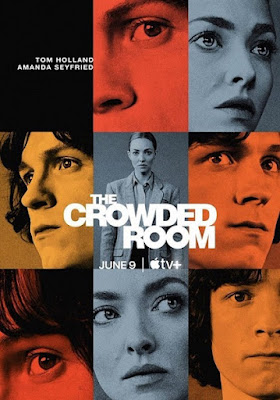

When Daniel Keyes first wrote Flowers for Algernon, it was considered

science fiction. Now, it is more like straight fiction, or maybe part of a very

small subcategory, along with Oliver Sacks’ novelistic nonfiction. Simply

knowing this series is “inspired by” one of Keyes’ “nonfiction novels” should alert

viewers to the nature of its strictly embargoed secret (which is pretty easy to

stumble across). Even if you do not know who Danny Sullivan is based on, it is

clear he needs a lot of psychological help in creator-writer Akiva Goldsman’s

10-part The Crowded Room, which premieres today on Apple TV+.

If

you really think about it, even the show’s title is a spoiler, but fine, we’ll

keep humoring everyone. The extremely twitchy Sullivan has been arrested for

his role in a shooting in Rockefeller Center, an unfortunately high-profile

location, but his reputed accomplice and ambiguous girlfriend Ariana remains

at-large. Based on evidence found at Sullivan’s Queens home, Matty Dunne

invites Dr. Rya Goodman (whom he dated once and wouldn’t mind dating again) to

examine him. He thought the squirrelly kid could be the career-making case

study Goodman has been looking for and he might be right—or Sullivan might

become the rabbit-hole that professionally derails her.

If

you enjoy flashbacks, you will love the next nine episodes. Sullivan’s weird

behavior and crimes are clearly a product of his traumatic past. However,

proving that to a jury will be difficult, especially since Sullivan is unable

or unwilling to admit what happened. Goodman even struggles to convince

Sullivan’s public defender, Stan Camisa, a Vietnam veteran, who is

self-medicating his own trauma.

Set

in 1979, Crowded Room recreates period New York in all its grungy glory.

The directors, especially executive producer Kornel Mundruczo (who helmed White God), nicely build and maintain the tension of Goodman’s sessions with

Sullivan. The legal drama aspects of the series featuring Camisa and Goodman

are also quite compelling. However, Goldman’s decision to shape the material

into a psychological mystery-thriller was a mistake, because 95% of viewers

will guess what is going on. Seriously, you already get it, right? If not, you

will when you see how awkwardly certain characters interact.

If

Goldman really wanted to present Crowded Room as a big twist thriller,

he should have focused and concentrated the narrative into considerably fewer

episodes. He just could not preserve a sense of mystery over ten installments.

Be

that as it may, there are still some excellent performances in Crowded Room.

Tom Holland shows tremendous and convincing range as Sullivan. Frankly,

Christopher Abbott does some of his career-best work as Camisa. (It is also

worth noting, with the cancelation of The Winchesters, Crowded Room is

currently the only series dropping new episodes that features a Vietnam veteran

as a major character.)