Every record label that means something to fans has a very distinctive style

and sound, like Blue Note, Pacific Jazz, and Stax. That was certainly true of Casablanca

Records too. They recorded Buddy Miles and Hugh Masekela, but they are best known

for disco. Yet, their biggest, most profitable outlier was KISS, even though

they took a while to catch on. Timothy Scott Bogart brings his father Neil’s tenure

at the label to the big-screen as an ill-advised movie-musical in Spinning

Gold, which opens today in New York.

Neil

Bogart died at the premature age of 39, but he still tells his own story in his

son’s musical memory play. He was born Neil Bogatz in Brooklyn, but he was

eager to leave his modest roots behind. Music became his business, first as a

one-hit teen idol and then as an executive for MGM and Buddah records, where he

signed Gladys Knight and the Pips, the Isley Brothers, and Bill Withers, all of

whom get more screen time in Spinning Gold than a lot of Casablanca

artists, such as the Village People, Cher, and Lipps inc. (Considering the notorious

reception for the Village People’s 1980 film, Can’t Stop the Music, maybe

we shouldn’t blame T.S. Bogart for not tempting fate in that respect).

Fatefully,

when Bogart struck out on his own with Casablanca, his distributor, Warner

Music, tried to undercut their sales, so they started handling sales and

distribution in-house, at least according to the film. They had three acts that

would eventually be huge: KISS, Donna Summer, and George Clinton’s Parliament,

but all three struggled with their initial releases.

It

will be interesting to hear what KISS thinks of their portrayal in Spinning

Gold. They might either dig it or hate it. It could go either way. Ledisi

has a nice number as Knight (“Midnight Train to Georgia,” of course), but the

scene of Bogart shouting and gyrating to the sounds of Edwin Hawkins’ choir

(another Buddah signing) is pure cringe. At least it is rather amusing to watch

Sebastian Maniscalco mumble through his scenes as producer-composer Giorgio

Moroder, but Tayla Parx does not bear a strong resemblance to Donna Summer.

In

a way, Spinning Gold is a lot like Cadillac Records, simply replacing

Bogart’s relationship with Summer for that of Leonard Chess and Etta James. Bogart

and Summer kept it professional, not counting her orgasmic “Love to Love You”

session, another embarrassing cringe fest, but he rather openly carried on an

affair with Joyce Biawitz, KISS’s co-manager, who seemed to have an office at

Casablanca (presumably for the sake of convenience).

Fonseca

is fine as Biawitz and Michelle Monaghan plugs away valiantly in the thankless

role of Bogart’s thankless wife, Beth Weiss, but Jeremy Jordan (who was very good in Broadway's Bonnie & Clyde) dominates the film,

in the worst way possible, preaching to the choir and projecting to the back

balcony as Neil Bogart. His performance is exhaustingly showy. [Timothy Scott]

Bogart desperately needed to tone him down, but instead, it looks like his

direction consisted of texting “100%” emojis.

Apple TV’s TETRIS provides some entertaining international intrigue, but

it is also a good story of naïve capitalism triumphing over socialism and

corruption. EPOCH TIMES review up here.

Everyone knows SpaceX will beat NASA to Mars by decades, if not centuries. A new

start-up plans to do it sooner. Nobody has ever heard of them, which should

signal problems to their prospective recruits. Nevertheless, Alex McAllister is

eager to go. Supposedly, they can make the journey cheaper, because their

colonists are only going one way. For the depressed twentynothing, that is a

feature rather than a bug. He is still probably the only person who believes he

is Mars-bound in Kyra Sedgwick’s Space Oddity, which opens tomorrow in

New York.

McAllister

is still openly grieving the accidental death of his popular big brother, for

which he partially blames himself. At least training for the Mars mission has

given him a renewed sense of purpose, or so his mousy mother tells herself. On

the other hand, his father Jeff is openly skeptical of the mission. He would

much prefer his son take over the family flower farm, since his brother cannot

and his sister Liz moved away to become a high-powered corporate PR flak.

Since

he will be dead to the world, part of McAllister’s preparations involve purchasing

life insurance—nobody bothers to explain just how his heirs would produce a

death certificate to collect. The box needs to be checked regardless, so he

walks down to Mike Taylor’s insurance office, where his daughter now works.

Daisy Taylor already had an annoying meet-cute with McAllister, so she indulgently

tries to craft a policy for his unusual circumstances. The more they see of

each other, the more she thinks she might like him, but he still isn’t ready to

rejoin life on Earth.

Alexandra

Shipp is enormously charismatic, so it is altogether unfathomably that she

could fall for a loser like McAllister. As awkwardly portrayed by Kyle Allen,

McAllister hardly seems capable of tying his own shoes. Frankly, walking and chewing

gum at the same time would be well beyond him, let alone astronaut training.

Not surprisingly, his chemistry with Shipp is unconvincing, despite her game efforts.

If the "aliens” let you see them, you have probably made some bad life

choices, because it means you are sufficiently isolated, both socially and

geographically, so that the “visitors” are not worried about what you might try

to tell anyone. Maggie’s dad Lloyd is a case in point. He lives in the Oregon

woods obsessively documenting “UFOs” in the night sky. The situation is a bit

of a concern to her, but staying with him is a great way to hide from the rest

of the world in Alex Lehmann’s Acidman, which releases tomorrow in

theaters and on VOD.

Apparently,

local kids mockingly call Lloyd “Acidman,” as Maggie deduces from the spray

paint defacing his ramshackle cottage. She was not able to warn him of her

pop-in visit, because Lloyd has gone completely off the grid and has no phone.

He is definitely surprised to see her, in an awkward, not especially welcoming

kind of way.

However,

he starts to warm to her, largely thanks his dog Migo, who sort of acts as their

mediator. He even trusts Maggie enough to take her out for a UFO sighting,

watching tiny specks of light vaguely moving along the horizon. So, Maggie

clearly recognizes the situation is not ideal. Unfortunately, this maybe isn’t

the most stable period of her life either.

There

is a good chance one of both of them could use some counseling, but the

screenplay (by Lehmann and Chris Dowling) never gets that far. Instead, the film

focuses on their halting attempts to reconnect as father and daughter. The UFO

themes are handled more in the tradition of UFOria than Close Encounters.

This is an achingly well-intentioned film, executed with great sensitivity, but

it is all very small in scope.

This is a very Cornish film, but at least it was not produced in the Cornish

language, which would have been a “performative” gimmick. Yet, in a way, it

hardly would have mattered considering how little dialogue there is in this 16mm

exercise in isolation and dread. The lonely landscape and Cornwall’s tragic

history contribute to a woman’s descent into madness during the deliberate course

of Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men, which opens Friday in New York.

We

only know the woman as “The Volunteer,” who has come to the deserted isle of

Enys Men (which translates to “Stone Island”) to observe the wildlife,

particularly a patch of wildflowers. It is a methodical routine, with little

variation, at least initially, but that appears to be what the Volunteer wants.

At night, she still maintains her personal rituals, including reading A

Blueprint for Survival, a 1970s environmental tract that may have directly

contributed to her impending doom. Her only company comes from the occasional

scheduled supply runs from the “Boatman,” who seems to mean more to her than a

mere deliveryman.

Jenkins

repeats this pattern over and over again, so the audience can pick up small

deviations when they first start to develop. It begins with small lichen appearing

on the Volunteer’s wildflowers. Then the fungi starts growing on her long-healed

scar. Here and there, we see ever-so brief flashes of visions or

hallucinations, harkening back to the Bal Maidens and the isle’s long-deserted

mines.

A

pat description of Enys Men might be “experimental folk horror.” As a

filmmaker, Jenkins clearly exhibits avant-garde and ethnographic sensibilities.

The film has a remarkably vivid sense of place—nearly to the exclusion of

everything else. Yet, he milks a palpable sense of mounting dread from the

eerie standing stones and abandoned monuments, quite skillfully.

Jughead Jones suddenly found himself back in high school. The good news is he

did not wake up naked on the last day of finals, for which he hadn’t studied

for. Instead, he is in an alternate 1950s Happy Days-style universe—and he

is the only one of his friends who remembers the first six seasons of Riverdale.

Jones and the Archie comics gang go back to high school, where fans

always remember them, in the seventh season of Riverdale, which

premieres tomorrow night on the CW.

At

the end of last season, Jones’ psychic girlfriend Tabitha Tate and their

friends tried to save the Earth from Comet Bailey, but they failed. At the last

second, Tate managed to send them back into the alternate past, so they can

regroup and hopefully develop a plan B. However, only Jones initially remembers

their past/future, whereas the rest of the group is busy living in the

alternate 1950s.

According

to Jughead’s narration, 1955 was a terrible time to be a teenager, but he has

no idea how wrong he is. Before the Progressive Era, there were no “teens,”

just people who were old enough to work all day in factories and those who were

not (as the doc Teenage explains). Even for teens, there was little work

available during the Great Depression, while eighteen-year-olds faced the prospect

of military service during the Korean War, and the two World Wars. It was also in the 1950s that the

segregationist policies initiated by Woodrow Wilson were finally effectively

challenged, notably with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Ed decision and Eisenhower

sending troops to integrate Little Rock schools in 1957. Seriously, 1955 is

pretty choice-year to land in, given the grimmer possibilities.

Yes,

the nation was still far from perfect, as the season premiere, “Don’t Worry

Darling,” makes abundantly clear with its focus on the Emmitt Till murder. The

Tate who doesn’t remember Jughead spends most of the episode trying in vain to

cover the lynching in the Riverdale school paper, with Betty Cooper’s help. It

is decent student drama to supplement Jughead’s efforts to figure out their situation,

while he still remembers. For those coming in cold, Cole Sprouse’s nebbish

charm as Jones and Camilla Mendes’ femme fatale turn as Veronica Lodge definitely

standout amid the established ensemble.

However,

there is not a lot fantastical or menacing business going on in the second

episode, “Skip, Hop, and Thump!,” which focuses on several characters’

repressed sexuality. The percentage of Riverdale students identifying (secretly)

as lgbtq is statistically unlikely, but Riverdale has always existed in a world

of its own. At least, at the very end, it introduces a promising storyline that

will presumably become a major focus throughout the final season.

As

we learn more fully in “Sex Education,” it seems that Jones’ comic artist

friend will be suspected of killing her awful parents in a way very much like

that depicted in one of the horror comic books they just started freelancing

for. This is definitely a geek-friendly arc that directly pays homage to EC

Comics and their battle with the Progressive, Puritanical Comics Code.

Grown adults who wear spandex richly deserve to be mocked. Unfortunately,

satire has been choked unconscious by woke social justice warriors, just as the

superhero genre peaked. Hollywood no longer has defiantly rude satirists like

Mel Brooks. The closest we can get is the post-modern bizarro wackiness of

Quentin Dupieux, from France. Whenever a rubber-suited monster attacks, the Tobacco

Force is there to stop them in Dupieux’s Smoking Causes Coughing, which

releases this Friday in theaters and on-demand.

Usually,

the fab five can rely on their marital arts skills to defeat the human-sized

kaiju they fight. However, when all else fails, they can call on the carcinogenic

compounds for which they are named, to give their foes an immediately fatal dose

of cancer. Benzene is the oldest, so he considers himself the group’s leader.

Mercury is a family man, whereas Menthanol is a luckless loser with the ladies.

Ammonia is the baby of the team, whereas Nicotine carries a torch for their boss,

Chief Didier, even though he is a human-sized rat, with greenish slime oozing

from his mouth.

After

their last rocky encounter. Chief Didier orders them off on a team-building

retreat. As they pass the time, they tell a series of campfire stories that are

meant to be scary, but are really just indescribably bizarre and random, very

much like Dupieux’s films. Unfortunately, while the Tobacco Force cool their heels,

their intergalactic nemesis, Lezardin, is planning Earth’s final destruction.

In

this case, a comparison to Brooks is quite apt, because sometimes Dupieux’s

gags are riotously funny and sometimes they fall excruciatingly flat, but he

keeps blasting them at the audience with a scattergun, regardless.

In the 1970s, criminals seeking to escape justice, like the mastermind of

the Fountain Valley mass murders, not infrequently hijacked flights to Cuba,

where they were sheltered by Castro’s Communist regime. Unfortunately, Dr. Ben

Song suddenly finds himself serving as a flight attendant aboard one such

hijacked flight, but their destination is a watery doom. Obviously, Song needs

to save the passengers, but he must do so without the help of Ziggy, the

project’s AI in “Friendly Skies,” the latest episode of Quantum Leap, premiering

tonight on NBC.

In

the previous episode, Janis Calavicci finally figured out the source of the Quantum

Leap project’s leak: Ziggy, their AI. Despite Ian Wright’s whining, Magic

Williams takes Ziggy offline, insisting they rely on the rest of the vast

computing power at their disposal. That might slow the team down a bit, but it

is pretty easy to figure out what Song is supposed to do.

His

flight went down somewhere in the Atlantic, while in a dead spot for

communications. At first, there are several possibilities, but again, the

hijackers make it rather easy to figure out once the hijackers reveal themselves.

It

turns out passenger attitudes towards flight attendants were not particularly

enlightened in 1971. However, there is more to this episode than gender issues.

The hijackers, who will potentially kill every soul onboard, are explicitly

motivated by class warfare rhetoric. In fact, they have expressly chosen this

flight because the airline owner’s son is among the passengers. Initially, Song

assumes he is a spoiled brat, but he slowly learns there is more to the awkward

teen than he realized.

The Morpho is like the Polybius of fortune telling machines. One day, it

just appeared in Deerfield’s general store. For a handful of quarters, it

promises to tell your “true potential.” Some are impressive, like the “royalty”

card received by Cass Hubbard, but for some, their Morpho cards become a source

of shame. Soon, the Morpho machine turns the town upside-down in creator David

West Read’s ten-episode The Big Door Prize, based on M.O. Walsh’s novel,

which premieres Wednesday on Apple TV+.

Dusty

Hubbard is a likeable, mildly under-achieving high school history teacher, who lives

happily with his wife Cass and their daughter Trina. When the Morpho appears,

he intuitively resists, especially because he is somewhat intimidated by his

wife’s “royalty” potential.

His

student Jacob Kovac is not a Morpho fan either. Poor Kovac already has more

than enough to deal with. He can hardly talk to his father Beau, who is still

bitterly grieving the death of his identical twin brother, the school’s star athlete.

Unbeknownst to anyone else, Jacob Kovac was cheating with his brother’s neglected

girlfriend, Trina. They are trying to secretly continue their relationship,

while grieving as the town expects. However, the Morpho seems to know, judging

from her card. Jacob’s card is something radically different, but it carries even

more stressful implications.

Father

Reuben has a complicated response to the Morpho machine. He understands the

importance of interpreting signs. Indeed, he was led to Deerfield by signs that

seemed prophetic at the time. While the series has a somewhat ambiguous

attitude towards the priesthood as a chosen profession, Father Reuben himself

is an entirely sympathetic character.

It

is hard to precisely categorize Big Door Prize, but Read (a writer and

producer on Schitt’s Creek) uses the fantastical element to create a surprisingly

funny small-town sitcom. Admittedly, the neuroses of both Dusty and Cass Hubbard

are often grating, but Read and the writers constantly puncture their pretensions

and expose their self-importance.

On

the other hand, there is some terrific chemistry that develops between Djouliet

Amara and Sammy Fourlas as Trina and Jacob. We clearly root for them as a

couple, despite all the complications of their relationship. Likewise, Damon Gupton

and Ally Maki are weirdly engaging as Father Reuben and Hana, the town’s new bartender,

who seems wholly unphased by the Morpho phenomenon—but something about the good

Father might just be getting to her.

This is another example of how DC films have been much more rewarding than Marvel

films. Most Marvel films build to an incomprehensible third act of whirling,

swirling CGI, after foisting off meaningless character cameos, to establish

films that won’t be released for months, if not years. In contrast, DC had The

Batman, which is more like Se7en than a traditional superhero movie

and Joker, which wore its Scorsese influences on its sleeve. DC animated

films have been especially willing to break established molds and formats.

Following in the tradition of Batman Ninja and Superman: Red Sun,

Batman gets a Lovecraftian twist in Christopher Berkeley & Sam Liu’s Batman:

The Doom that Came to Gotham, adapted from Mike Mignola & Richard Pace’s

limited comic series, which releases Tuesday on BluRay.

Prof.

Oswald Cobblepot is not the Penguin in this universe, but his Wayne Foundation-funded

arctic exploration turned out rather badly. By the time Bruce Wayne and his

adopted orphans arrive to investigate, only Cobblepot and another crew member

still survive, but they under the control of an ancient, cosmic demon. Wayne tries

to bury the evil in the Arctic, but it remains hidden in the soul and body of

his deranged prisoner.

Back

in Gotham, Wayne receives a warning from Etrigan, the not-entirely evil demon,

about the scope of the supernatural threat facing Gotham. It seems Ra’s al Ghul

(the traditional occult supervillain of the Batman franchise) is trying to

usher one of the elder gods into our world, via Gotham, of course. To stop him,

Batman enlists the help of Oliver Queen, who is not the Green Arrow this time

around, but he is a bow-hunter. He also shares a fateful connection to Bruce

Wayne.

The

way a lot of these alternate-world DC films reconceive their characters to fit

a radically different context is often quite clever. In this case, it does not

take much shoehorning to fit in Ra’s al Ghul, Jason Blood/Etrigan, and Kirk

Langstrom/Man-Bat. Probably, nobody is more greatly reinvented than Queen, but

it is hard to imagine many hardcore Green Arrow fans objecting, because he is the

film’s best character.

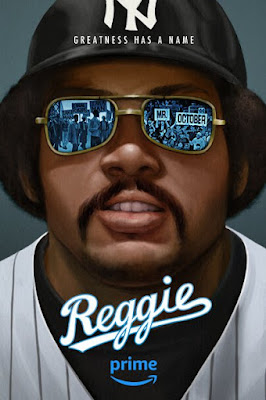

Along with Pele, he was the personification of New York sports in the

late 1970s. Reggie Jackson’s play on the field and his contentious relationship

with Yankees manager Billy Martin were welcome distractions from “The Summer of

Sam.” However, Jackson nearly became a notorious murderer himself, when he was brainwashed

to assassinate the Queen in The Naked Gun. That is way more movie

references than most athletes get, but Jackson was always at the center of the

New York media’s attention, whether he liked it or not. Jackson looks back at

his career highs and controversies in Alex Stapleton’s documentary Reggie,

which premiers today on Prime.

For

baseball fans, hearing Jackson take a call from Pete Rose at the beginning of

the film might just overshadow everything that follows it. Jackson always shot

from the hip, despite taking flak for it, so his candor in Stapleton’s film

should not be a surprise. Jackson has a lot to say about black participation in

Major League Baseball, both past and present. He also has a lot to unpack from

his own career, including five World Series rings and two World Series MVPs.

Jackson

won three World Series in Oakland, made the post-season twice with the

California Angels and now works for the Houston Astros, but he will always be

remembered as a New York sports legend. Therefore, it is fitting both Derek

Jeter and Aaron Judge make appearances to discuss Jackson’s mentorship.

Surprisingly,

the late George Steinbrenner’s image might be somewhat burnished by the film.

On the other, it might lower Billy Martin’s stock. Regardless, watching Reggie

will bring slightly more mature fans right back to the time when the

manager was constantly generating NY tabloid headlines, right alongside Jackson.

Love him or hate him, a good Billy Martin doc is seriously overdue.

Jackson

has a lot to say about the state of the game and society, which is important,

but the fun parts feature Jackson reminiscing with his friends and teammates,

like Rollie Fingers and Dave Stewart. There is also a lot of material that will

be new to more casual baseball fans, like Jackson’s unsuccessful bid to buy the

LA Dodgers, which didn’t fail due to a lack of money, considering Bill Gates

and Paul Allen were part of his management group.

Among gangster films, this one is unusual, because almost none of its

characters went to prison, but the director did. His crime was being Ukrainian

in Crimea, which is weird, considering all decent countries recognize Crimea as

part of Ukraine. Tragically, Putin saw it differently. Sentsov’s 2015-2019

stint in a Russian prison earned the director the Sakharov Award from the European

parliament. Today, the film’s leading man is fighting for his country on the

frontlines. Obviously, the current Ukrainian government has an antagonistic

relationship with Russia, but that was much less so during the lawless 1990s,

when Sentsov’s film is set. Life is hard and so is our protagonist’s head in

Sentsov’s Rhino: Ukrainian Godfather, which releases this Friday.

There

was a time when Rhino was a bullied little boy named Vova. However, the older

he got, the tougher he had to be. His upbringing under his alcoholic father was

not easy, as we see in an absolutely amazing time-lapse tracking shot that must

quite a challenge to set-up. At first, Vova was just a street thug, but when he

tangles with the wrong mobbed-up gym, he enlists with a rival gang for

protection.

While

his nickname is initially a source of embarrassment, its brutish implications are

helpful to his reputation. After a period of slow but steady advancement, Rhino

starts to make some aggressive moves of his own, which have violent consequences.

In fact, he will regret many of his life choices, as the older, world-weary

gangster confides to his mysterious companion, during the looking-back-in-retrospect

flashforwards.

Rhino

is

too naturalistic to be a proper slam-bang gangster movie, but it is also much more

violent and plot-driven than the average art-house social issue film. It very

definitely tries to capture the vibe of 1990s that cause the disillusionment

that contributed to the troubles of the 2000s. Had this period been more stable

and transparent, it is less likely a Russian-aligned thug like Yanukovych could

have risen to power. Indeed, this film is absolutely marinated in regret, on

both the individual and collective levels.

In lighthouse and deep-sea oil rig movies and series, like The Vanishing

and The Rig, characters often feel like the rest of the world might have

disappeared, leaving them stranded forever. For the rag-tag crew aboard this

post-apocalyptic ocean fort, that is a very real possibility. Their relief is distressingly

late and some of them are starting to act a little stir crazy in Tanel Toom’s Last

Sentinel, which opens this Friday in theaters.

The

seas have risen, but the two tiny surviving nations remain perpetually at war. It

is just four of them manning this remote, seabound military outpost (modeled on

WWII Britain’s Maunsell forts), but Sgt. Hendrichs will not let any of them

slack off. Cpl. Cassidy tries to be an intermediary between him and the grunts,

Sullivan and Baines, but it isn’t easy. Their relief is way, way overdue, but

when a ship finally arrives, unannounced, it is a cause of concern rather than

relief. In fact, Hendrichs almost uses the fort’s super weapon to blow them all

up.

That

would have been a mistake, but the empty vessel is still disconcerting. At

least it isn’t full of rats, like in Three Skeleton Key. It also holds

some supplies, as well as a good deal of mystery. Regardless, it is still a

sea-worthy ship, but Hendrichs is not about to let the squad abandon their post.

The

basic concept of this Waterworld-like world is familiar, but the

execution of the Estonian Toom (an Oscar nominee for the short film, The Confession)

is notably strong. The initial encounter with the derelict ship is surprisingly

tense, as are several subsequent sequences. The isolated setting is definitely

eerie and the spartan set design is highly effective. It all looks great, but

unfortunately, some of screenwriter Malachi Smythe later plot points stretch

credibility.

Vicky Soler is sort of like Inuyasha or Goku from Dragon Ball, but

instead of an anime hero, she is a bullied biracial French girl, who happens to

have an uncannily powerful sense of smell. She can identify and reproduce

anyone’s smell—and maybe even use that aroma to travel into their past. Her

family’s traumatic history turns out to be a really bad trip in Lea Mysius’s The

Five Devils, which opens Friday in New York.

Vicky’s

mother Joanne is distant, but that just makes her daughter even more codependent.

Her parents have a polite but obviously passionless marriage—to the point that

even Joanne’s crusty old father is offering her Dr. Ruth advice. Young Soler

has saved her mother’s scent, via some of her excess body lotion, which she

uses for a hit of motherly togetherness whenever Soler cannot be bothered with

her daughter. However, her latest huffs take her back in time, to her mother’s

high school years.

Those

time-travel interludes take on greater significance when she finally meets her

Aunt Julia, her father Jimmy’s sister, who was recently been released from

prison. Everyone in their small Alpine town seems to know about Julia Soler’s episode,

except Vicky. Regardless, she soon gets an eyeful of her mother’s erotically

charged relationship with Aunt Julia, before she married Vicky’s father. Weirder

still, the teenaged Aunt Julia of the past, appears to know when Vicky is

watching.

Five

Devils

is hard to exactly classify because it contains slippery elements of time-travel

science fiction, dark fantasy, and magical realism, but the underlying

fantastical engine driving the film mostly works. When you get the full picture

of the ironic cycle the family is caught up in, it really is quite compelling. Viewers should still be

warned, the first ten or fifteen minutes of scene-setting and dramatic establishment

are rather cold and standoffish, but once the film gets going in earnest, it is

strangely hypnotic.

Most young filmmakers are desperate for their first directing credit, but for

the journalists and documentarians who constitute the The Myanmar Film

Collective, identifying themselves would have lead to imprisonment, torture,

and death. Laudably, the non-Burmese who also contributed to this documentary,

also declined credit, as an expression of solidarity. Their brave underground films

shame the international media, who have largely under-reported the human rights

abuses following the February 1 coup. Here’s a “trigger warning:” reality is

brutal in The Myanmar Film Collective’s Myanmar Diaries, which premieres

Friday on OVID.tv.

One

thing is crystal clear from all the constituent parts of Myanmar Diaries—the

military regime has turned the nation into a true police state. No other words

describe the conditions the Burmese people live under. Several of the most

visceral and shocking segments were shot on smart phones or handheld devices.

Frankly, most or all of them should have gone viral worldwide, but most viewers

will likely see them here for the first time.

The

audience will witness protestors shot down, mothers dragged out of their homes

while their scared children cry and wail, as well as a defiant man

live-streaming his attempt to hold back the warrant-less police trying to break

down his door in the dead of night. On the other hand, we also see the

resistance, who clearly represent the vast majority of the people. By far, the most

memorable is the outraged auntie, who defiantly gives the “anti-riot” cops a verbal

dressing down sufficient to shame them all back to the stone age.

Perhaps

less consistent are the impressionistic interludes that express the fear,

paranoia, isolation, and loneliness of ordinary Myanmar citizens. You could

argue without irony that the entire film counts as a “horror” movie of sorts,

but the most successful interlude uses the visual vocabulary of horror movies

to represent people’s current fear.

In the original Quantum Leap series, Dr. Sam Beckett encountered “evil

leapers,” who were trying to set wrong events that had gone right. Dr. Ben Song’s

rival, Richard Martinez, a.k.a. “Leaper X,” insists he is not one of them, but

he would say that, wouldn’t he? Regardless, Song finds himself reluctantly working

with his presumed antagonist in “Ben, Interrupted,” tonight’s episode of Quantum

Leap.

This

time around, Song’s host is a private detective going undercover in a notorious

1950s mental asylum, sort of like Nelly Bly did, but without a good exit strategy

in place. Fortunately, Song has the Quantum Leap team and their AI, Ziggy, to

help guide him. His mission is to rescue his client’s sister, who was committed

by her husband, for the sake of a quick and easy divorce. However, Song probably

won’t be able to leap if one or both of them is lobotomized.

As

a further complication, Martinez leaps into the body of one of the thuggish orderly-enforcers.

He claims he wants to help, but Song is understandably wary. Nevertheless, he

does not have a lot of options.

This

is the first episode in a while that really digs into the “Leaper X” subplot. In

addition, there is also more intrigue and drama involving Janis Calavicci, who

apparently assisted Song make his unsanctioned leap. That means this episode

really involves time travel, rather than mere small-bore family melodrama. The

stakes are also huge, at least for Song.

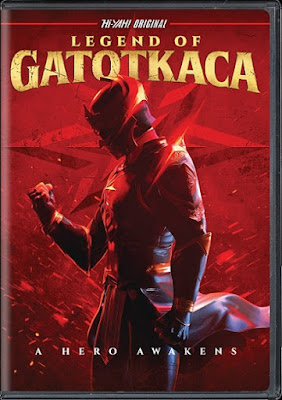

This is the first cinematic foray into the Indonesian “Satria Dewa” superhero

universe—and probably the perfect time for it, considering how stale the Marvel

and DC franchises are getting. At least this is something different, inspired

the Mahabharata, albeit in a very modernized kind of way. Our hero still

fights the Kaurava, but now they are more like an evil, genetic secret society

in Hanung Bramantyo’s The Legend of Gatotkaca, which releases tomorrow

on DVD.

Yuda’s

mother Arimbi barely saved her son from a sinister supervillain, but the battle

cost her memory. Since his teen years, Yuda has cared for her, dropping out of

school to earn money. He therefore hoped to at least vicariously enjoy his

well-heeled friend Erlangga’s graduation, but instead the valedictorian is

mysteriously murdered on-stage.

Many

of Jakarta’s best and brightest have recently fallen victim to a serial killer,

who has the cops baffled. Of course, it is not really a mortal agent doing the

killing. It is the Kaurava secret society, especially Beceng, their chief

costumed assassin, who is knocking off those who carry the rival Pandava gene.

Beceng also killed the father and brother of Dananjaya, who is sort of like the

Hawkeye of the Satria Dewa universe. As Yuda starts asking questions, he meets

the small band of Pandava resistance against the Kaurava cabal, led by Dananjaya.

Yuda

also forges and alliance and perhaps something more with Agni, the daughter of

Erlangga’s professor. With all their help, Yuda will unlock the secret of his

mother’s mysterious heirloom, which holds the power of Gatotkaca, but he still

has a lot of butt-kickings in-store for himself, at the hands of Beceng and the

Kaurava.

Or

something like that. Bramantyo and co-writer Rahabi Mandra lean into the series

lore, presumably to please pre-existing franchise fans, but they often leave

newcomers a bit confused. Regardless, if you consider the film a Sanskrit

fusion of The X-Men and Underworld, you might generally get the

idea. In fact, many of the Javanese elements make a refreshing change from the vanilla

superhero movies Marvel and DC have been churning out (more Ant-Man and Shazam

movies, really?).

The

action is also pretty intense. Let’s put it this way, Yayan Ruhian (“Mad Dog”

from The Raid) plays Beceng—and he hasn’t lost a single step. He

definitely delivers in the fight scenes, making a spectacularly nasty bad guy.

Swedish-speaking Finnish writer Tove Jansson’s Moomins characters are popular throughout

Europe and maybe even more so in Japan, where there have been numerous anime

adaptations and one of two Moomins theme parks. However, they have a smaller

cult following here in America, mostly from fans of Japanese animation. The British

dub for Sky TV could still find an audience here, if a streamer picked it up,

given the voice talent (including Kate Winslet and Taron Egerton during earlier

seasons). For Moomins lovers, three episodes of the third season screen again

today during the 2023 New York International Children’s Film Festival.

Moomins

look like hippos, but they are trolls—of the pre-social media variety. They are

also quite sweet-tempered. It is mostly Moomins in Moominvalley, but they are a

few other creatures, like the Kangaroo-looking Sniff and some humanoids, who

are referred to as “Hemulens.” Perhaps for accessibility’s sake, the three

episodes selected for NYICFF feature the Moomins helping their human friends.

In

“Toffle’s Tall Tales,” Moomintroll (son of Moominpappa and Moominmamma) and

Sniff help the five-year-old-looking little boy Toffle, who was changed to

non-binary in this series (to appease the new kind of woke trolls), find a safe

place to stay while the residents of Moominvalley hibernate. Their journey gets

thoroughly complicated by Toffle’s penchant for spinning outrageous yarns. Conveniently,

Jansson has been dead since 2001, so she had no feedback on the revision to her

original character.

In

“Miss Fillyjonk’s Last Hurrah,” Moomintroll misdiagnoses a tiny chicken bone

lodged in her throat as inevitably fatal, so instead of trying to cure her, he

convinces his severe spinsterish neighbor to finally enjoy some adventures in

life, while she can. It is a very O. Henry-ish “carpe diem” episode, but

pleasantly so.

Finally,

in “Snufkin and the Fairground,” Moomintroll’s best friend (who displays

anarchist tendencies in Jansson’s books) takes over a popular amusement park,

after the previous owner resigns. Not surprisingly, he turns out to be a weak

manager.

The Twilight Zone had

its share of extra-terrestrials, but first contact and alien invasion were really

specialties of The Outer Limits. The was true right from the start—the very

start. The first episode aired that under the title, “The Galaxy Being” was

very slightly re-edited from the unaired pilot, appropriately known as “Please

Stand By.” That “being” was from another galaxy, who did respond well when he

suddenly found himself in our world. In honor of the show’s 60th

anniversary, the original pilot screens tonight at UCLA.

Sit

back and enjoy, because cosmic forces will be controlling the transmission we

are about to watch. Allan Maxwell is a brilliant scientist, who uses his radio

station as a cover for his underground SETI research. Basically, his DJ-brother

Gene “Buddy” Maxwell programs polite jazz and bachelor pad-ish easy listening.

It was probably a good spot on the dial to hear Joe Bushkin and Eddy Duchin, if

you could pick-it up. Dr. Maxwell deliberately keeps the output low, so it does

not interfere with his own experiments.

Much

to his surprise, Maxwell’s microwaves create a link through which he and a

mysterious alien from Andromeda start communicating. The scientist could continue

their trans-galactic exchange all day, but his wife insists he attend their

local town’s long-planned awards ceremony in his honor. He turns the station’s

output down even further, to maintain a stable connection, while the “Galaxy

Being” “holds the line,” but the fill-in DJ cranks it way up, inadvertently

dragging the alien into our world. Havok soon follows.

Obviously,

the network picked up Outer Limits, but they had creator Leslie Stevens

(who wrote and directed the pilot) somewhat water-down its intensity. They also

cut a line from the Galaxy Being that suggested his people might just come to

Earth and kick our butts, now that they knew of our existence. That is

especially unfortunate, because it represents one of the earliest pop-culture manifestations

of Cixin Liu’s “Dark Forest” concept, decades before the Chinese novelist’s Three-Body

trilogy.

Playing pinball is sort of like the video game experience, except the ball and

flippers are actually real. The game seems cool in a retro way now, but it was

some of the most fun you could have for a quarter in the early1970s.

Unfortunately, it was still banned in New York City, thanks to the Puritanism

of the Progressive reform movement. Inexperienced GQ journalist Roger

Sharpe played a major role in legalizing the game. Sharpe’s campaign for pinball

respectability is quite charmingly dramatized in Austin & Meredith Bragg’s Pinball:

The Man Who Saved the Game, an MPI-supported film, which releases today on

VOD and in select theaters.

As

a divorced twenty-five-year-old with hardly a quarter to his name, Sharpe came

to the City with vague dreams and limited prospects. However, when he finally

found a pinball machine, in an adult bookstore, the college pinball wizard

started to get his groove back. Then the store was raided—for the pinball

machines, not the porn.

By

this time, Sharpe had secured a junior writing position at GQ. He also

started dating Ellen, a very pretty but somewhat older single-mother working in

the same office building. First, Sharpe parlays his pinball outrage into his

first major GQ piece. After that, he is able to secure a book deal for

his illustrated pinball history. In the process, he interviews all the founding

fathers of the much-maligned pinball industry. As a result, he starts to make a

name for himself as a pinball expert. Soon, the trade industry group covering

pinball approaches Sharpe to testify on behalf of the game in front of the New

York City Council, but Sharpe is leery of potential negative attention.

Given

the title, it is probably a safe bet that Sharpe “saves the game,” or at least

contributes to the repeal of New York’s ban. However, the Braggs still make the

drama surprisingly pacey and entertqainingly grabby. Their use of the older, third-wall-breaking

Sharpe to offer sly commentary on the unfolding action works much better than in

previous films. Thanks to Dennis Boutsikaris’s portrayal of the somewhat more

mature and graying Sharpe (who was onboard with the film, as an executive

producer), all the exposition is weirdly fun and amusing. Frankly, we could

listen to an entire multi-part documentary, featuring Boutsikaris adopting

Sharpe voice, to talk about pinball history.

Yet,

throughout the film, the Braggs give equal weight and significance to Sharpe’s

relationship with Ellen and her son, Seth. As Sharpe, Boutsikaris explicitly

says there are things that are more important than pinball, in almost exactly

those terms. That means the younger Sharpe has more to do once he “saves the

game,” which is a refreshing break from the typical climatic testimony cliché.

As

Roger and Ellen, Mike Faist and Crystal Reed (also very good in Swamp Thing)

have insanely appealing chemistry, right from the start. Their relationship necessarily

has its ups and downs (otherwise this would be a pretty dull film), but viewers

immediately start rooting for them. It is also worth noting the work ethic and

values espoused by Ellen, who at one point explains how she grinds away as a

secretary to provide for her son, in order to avoid resorting to welfare. That

is really quite something to hear in a film.

Faist

and Reed are terrific handling the grounded romantic comedy. Bryan Batt and

Mike Doyle also deliver a lot of snarky laughs as Harry Coulianos and Jack Haber,

the now legendary art director and editor of GQ. Among other things, Pinball

nicely recreates the groovy milieu of 1970s magazine publishing.

The Norse Wolf Cross looks satanic, but it is actually Pagan. Either way, it

is a handy symbol for a horror movie. Hunter White was found with one when her

adopted father, a cop, responded to a call, regarding a baby wailing in a cemetery.

Having taken DNA tests and done extensive research, she secretly visits Norway

in search of her roots in Alex Herron’s Leave, which premieres on

Shudder tomorrow.

White

told her father she was leaving to start college at Georgetown (where The

Exorcist was set, a completely unrelated fact), but she is headed to Norway

instead. Her DNA is 99% Norwegian and she discovered Cecilia, a Norwegian Death

Metal vocalist, was playing in Boston the night she was abandoned. Despite a

rocky start, Cecilia turns sympathetic, deducing White is the birth daughter of

her now-institutionalized bassist, Kristian, and Anna Norheim, the girlfriend

her presumably murdered in a particularly grisly fashion.

From

there, Hunter follows the trail to the Nordheims, who are welcoming, but also

suspiciously hardcore fire-and-brimstone Christians. Some supernatural force

keeps telling White to “leave,” as per the title, but she keeps ignoring it.

That’s right, this film teases good old fashioned satanic panic, but turns into

to be all about evil Calvinists. It does not do itself any favors in this

regard. The film starts with the frighteningly evocative scene of White’s

discovery in the graveyard, but that is just about the film’s first, last, and

only scary moment. The rest is a bunch of silly stuff with sinister Evangelicals,

including a patriarch pushing eighty, who somehow consistently overpowers the

twenty-five year-old White.

When watching this documentary, the parallels between the Soviet Union’s

response to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster and the Chinese Communist Party’s

response to the Wuhan Covid outbreak look eerily comparable. Reports were

covered-ep and whistle-blowers were silenced, resulting in thousands of deaths

that might have been prevented. Yet, Nobel Prize winning oral historian

Svetlana Alexievich’s book was not just an expose. It also thoroughly documented

and expressed the love and grief of survivors. Luxembourgian filmmaker Pol

Cruchten adapted her book with his artistically rendered documentary, Voices

from Chernobyl, which premieres today on OVID.tv.

The

words are spoken in French, but they are adapted from the Ukrainian and Russian

of survivors—if “survivor” is the right term. Many widows of reclamation

workers and fire-fighters remain in mourning years after the disaster.

Alexievich also talked to a teacher, who explains how damaged her young

students have been by the incident. Physically, they are under-sized and

sickly, while psychologically, they are preoccupied with death.

Counter-intuitively, she are her colleagues are oddly pleased to see any signs

of traditional school children misbehavior, since it signals signs of inner

life.

We

also hear (or in many OVID viewers case, read in subtitles) the words of the

chief of the Belarusian nuclear authority, who had cautionary reports regarding

the Chernobyl disaster stolen from his office. Had the authorities acted on his

warnings, it would have saved hundreds of lives—maybe thousands, but the

Soviets preferred to pretend nothing was wrong, in hopes of avoiding an

international propaganda disaster. The lives of thousands of Ukrainians were

disposable towards that end. Remember, good old Mikhail Gorbachev was General

Secretary at this time—you can see his rotting portraits abandoned throughout

the wreckage of Pripyat Cruchten’s cameras capture.

Instead

of talking heads, Cruchten superimposes the words of Alexievich’s interview

subjects over scenes of ghostly Pripyat or carefully composed tableaux,

symbolically representing the horrors of Chernobyl. Stylistically, it is a lot

like experimental hybrid films, such as Scars of Cambodia or Into the Crosswind. Cruchten’s cast are more like interpretive dancers than

traditional thesps, but there is definitely something acutely expressive about

their screen presences.

Drive-ins were widely considered the big winner of Xi’s pandemic, because they

were the only theaters open during the shutdown—but not so fast, mister. It

turns out they also suffered from the same supply chain issues and staffing

woes that affected every other company. Often, opportunity turned into

frustration, but drive-in proprietors carried on. Writer-director-everything-else

April Wright follows eight drive-ins as they plug away amid the pandemic’s

aftermath in Back to the Drive-In, which releases today on VOD.

If

you have seen the documentary At the Drive-In about the Mahoning Drive-In in Pennsylvania, you will be familiar with the general state of

drive-in business. Converting to digital was a challenge for most, if not all,

but it was necessary to keep screening the latest Hollywood studio tent-poles.

Some, like Bengie’s Drive-In still largely feature new releases, except during

the pandemic shutdown, when they had to rely on older films.

However,

many drive-ins have found success with repertory programming. After all, what

sounds like more fun to watch on a hot summer night, a timeless favorite like Jaws

or Jurassic Park or the next Marvel product, carefully sanitized for

the Chinese market? In fact, the Greenville Drive-In really embraces the retro

rep spirit, designing special cookies and cocktails to accompany films like The

Great Lebowski (obviously, they were serving White Russians that night).

All

the featured drive-ins share a number of problems, like supply chain issues.

Everyone seems to have problems stocking staple items like popcorn cups. Of

course, they also complain about the cost of doing business with the studios.

However, the Wellfleet Drive-In on Cape Cod must contend with heavy fog that is

unique to their location.

One

of the cool things about Wright’s film is seeing the new Drive-Ins spring up, like

the Field of Dreams Drive-In the owners literally build in their Ohio back

yard. The owner-architects of the Quasar Drive-In in Nebraska emphasized nostalgia

in their design, incorporating vintage equipment acquired from shuttered

drive-ins around the country. Good luck to them both.

Honestly, the new leadership at Warners probably saved the DC franchise by axing

the unreleased Batgirl movie if reports were correct it killed off

Michael Keaton’s Batman. He was a lot of people’s introduction to the Caped

Crusader and superhero movies in general. Seriously, they bring put him back in

the mask, just to murder him? That would have produced some massive ill will. However,

killing off a hardly seen Batman in a CW show based on a DC video game is

another matter. Yes, Batman is about to die (violently), but his adopted son

and a rag-tag band of rejects hope to find his killer and clear their names in Gotham

Knights, developed by Natalie Abrams, Chad Fiveash, and James Stoteraux,

which premieres tomorrow on CW.

Turner

Hayes’ birth parents were also murdered, which was presumably why fellow “orphan”

Bruce Wayne adopted him. The wealthy philanthropist never revealed his secret

identity to Hayes. He seemed determined to keep his adopted son separate from his

Dark Knight world. Yet, he still trained Hayes extensively in martial arts and

fencing. The now-privileged teen only learns the truth when Batman is murdered,

presumably by Duela, the slightly unhinged daughter of the Joker and Harley

Quinn, and her current running mates, Harper Row (known in the comics as

Bluebird) and her trans brother Cullen.

Just

as Hayes and his platonic bestie, Stephanie Brown, start using the Bat-computer

to investigate possible payments to Duela’s crew, he finds himself framed as

the source of funds. Barely escaping the crooked cops trying to kill them, Hayes

reluctantly convinces the outsider-weirdos to team-up to prove their innocence.

In addition to Brown, they have an ally in Hayes’s classmate Carrie Kelley, who

also happened to be the final Robin—and isn’t wanted for murder.

Based

on mysterious coins that keep turning up, Hayes and company deduce the real

culprits are the Court of Owls, which is sort of like Gotham’s Illuminati, the

secret power pulling all the strings. Working with Duela and the Rows is not

easy, but as they start interfering with the Court’s criminal enterprises, they

gain a reputation as a new vigilante group dubbed the “Gotham Knights,” by a

press that is unaware they are also Gotham’s most wanted.

Gotham

Knights is

definitely a mixed bag, but the stuff that works makes it compulsively

watchable. As Hayes, Oscar Morgan too much of a cold fish to be a compelling

lead, but Olivia Rose Keegan is entertainingly twitchy and erratic as Duela.

Frankly, Navia Robinson portrays Kelley/Robin with the kind of grounded

charisma that should have made her the lead of the series, whereas the constant

whining of Fallon Smythe and Tyler DiChiara as the Row siblings gets to be a

chore to sit through.

Fortunately,

the series also gets some help from adults. Misha Collins is terrific as

District Attorney Harvey Dent, who will slowly start to believe Hayes’s claims

of innocence. Of course, since his name is Harvey Dent, he will have his own

issues to deal with. Doug Bradley (of Hellraiser fame) has one of the

best guest-starring turns of the year in episode six, playing Joe Chill, the

gunman convicted of killing Bruce Wayne’s parents, who wants to speak to Hayes

before he is finally executed.

1989 was a great year, except maybe here in New York. The city was about to descend

into a period of chaos, ended by Giuliani’s election in 1993. Dr. Ben Song will

not do anything to prevent that this leap. Instead, as a public defender, he

scrambles to save a young man who will be wrongly imprisoned for manslaughter

in “Ben Song for the Defense,” tomorrow night’s episode of Quantum Leap.

The

clever thing about this episode is it breaks format slightly, without really

breaking format. Since Addison Augustine’s military background was so helpful

to Song in the previous episode, she hands the holographic baton over to her

Quantum Leap Project colleague Jenn Chu, because of her knowledge of the legal

system. Chu got her legal degree while serving time, so the former hacker

certainly has some insights.

Unfortunately,

Song’s host is so overworked, because crime in New York is starting to explode,

she hardly has the time to give Camilo Diaz’s case the attention it deserves.

No, that is not how the series’ writers room spins things. Regardless, Song has

to get Diaz off, so he can save his younger brother from the gangs trying to

get their hooks into him.

There

is some decent courtroom drama in “For the Defense,” which harkens back to

classic episodes of the original series, such as “So Help Me God.” However, the

writers cannot help including little digs at the 1980s, which leads to some

credibility issues, like Song’s host being in a romantic same-sex relationship

with the second chair Assistant DA on her case.

A SPY AMONG FRIENDS is a carefully crafted espionage thriller that depicts the treachery and hypocrisy of Kim Philby. It turns out it was easier to admire the workers' paradise from afar than to live under it. EPOCH TIMES review up here.

This classic tale is all about a prince trying to save a princess and it

starts with a monster attack. We typically do not see it this way, but Mozart’s

most popular opera is a total quest fantasy. Therefore, maybe it isn’t totally inappropriate

to combine it with elements of Harry Potter, just slightly goofy. Young Tim

Walker does not simply study Mozart’s opera, he journeys into it in Florian

Sigl’s The Magic Flute, produced by Roland Emmerich, which is now playing

in Los Angeles.

Walker,

a Sensitive Andrea Bocelli copycat, has been granted rare permission to join

the student body of Hogwarts-like Mozart Academy of Music, because of the

recent death of his alumnus father. Before he died, Walker’s father asks him to

return the rare Magic Flute manuscript he nicked from the school’s

library. He tries to sneak it back his first night there, triggering the

mystical portal to the world of The Magic Flute.

Accepting

Prince Tamino’s quest, Walker constantly sneaks out of his room at 3:00 to

reinsert himself into the opera. His disappearing acts thoroughly confuse his

sidekick Papageno, the opera’s comic relief. Meanwhile, in the real world, his

flakiness annoys his roommate, Paolo, and his prospective girlfriend, Sophie.

The

look of both worlds is quite amazing. The “Potterizing” of The Magic Flute is

sometimes quite clever, but Walker really ought to be better prepared for the

trials he faces, considering how intently he studies the titular Mozart opera.

Regardless,

probably the best part of the film, both in terms of special effects and vocal delivery

is the Queen of the Night, played by real deal opera diva Sabine Devieilhe. She

definitely rises above the often-awkward-sounding contemporary English

translation of Mozart’s libretto.

Nobody

else can match her range, but wisely, Jack Wolfe and Niamh McCormack really do

not try, as Walker and his potential real-world love interest. Instead, they

perform some likable vintage pop. Their romantic chemistry is lightweight, but agreeable.

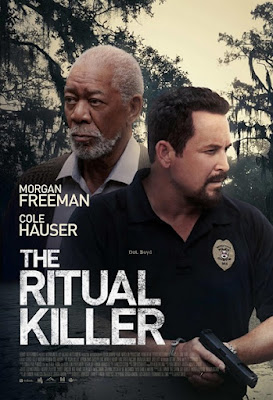

Who better to catch a serial killer than an eighty-something year-old

anthropologist? It probably makes more sense than asking another serial killer

for help, especially since Dr. Mackles is an expert in Muti, the traditional spiritual

medicine practiced in Southern Africa. It appears there is a rogue practitioner

committing sacrificial murders to benefit his clients in George Gallo’s The

Ritual Killer, which releases today in theaters and on VOD.

The

guilt Det. Lucas Boyd carries after his daughter’s death has left him nearly

non-functional, except when chasing violent criminals, who then bear the full

brunt of his rage. He and his partner start investigating a trail of bodies

mutilated with surgical precision that lead to the mysterious Randoku. The

large, scarred man definitely stands out, but he is still frustratingly hard to

catch.

To

interpret the African writing and exotic spices found at a crime scene, Boyd

enlists the help of Dr. Mackles, an African Studies professor, who is clearly

freaked out by them. Initially, he tries to play cool and beg off the case, but

he inevitably starts advising Boyd on the Muti aspects of the ritual sacrifices.

That

all sounds like a passable premise, but the screenplay (unpromisingly credited to

three scribes: Bob Bowersox, Francesco Cinquemani, and Luca Gilberto) proceeds

in such an orderly straight line, it turns into a total snooze. At least the

one moment of lunacy at the end gives viewers something to remember, but the

rest is the stuff of mediocre 1990s TV-movies.

The

legendary Morgan Freeman looks about as bored playing Mackles as he did in the

underwhelming Vanquish, which was also helmed by Gallo (maybe Freeman

should stop working with him). The saving grace is Cole Hauser, whose hard-boiled

brooding as Boyd is better than the film deserves.