Maurice Flitcroft wanted to be the real-life version of Kevin Costner’s “Tin

Cup,” but he just never played the game very well. Nevertheless, his record-setting

high-score at the 1976 British Open made him something of a cult hero to

frustrated duffers everywhere. After that, the British Open was very much done

with Flitcroft, but Flitcroft was not done with them. His unlikely career gets

the underdog movie treatment in Craig Roberts’ The Phantom of the Open,

which opens this Friday in theaters.

Having

always provided for his wife Jean, their twin sons Gene and James, and his older

step-son Michael, Maurice is not sure what he wants to do with himself as

retirement approaches for the working-class crane operator. Somehow, he gets it

into his head golf will be his thing. He has the ugly clothes, but his swing is

even uglier.

Naturally,

he figures he will enter the British Open, because it looks like a nice tournament

on the telly and because he can. That is why it is called an “Open.” It turns

out there is a lot less paperwork to enter as a professional rather than an

amateur, so that is what he does. Stodgy Keith Mackenzie of the R&A is scandalized

by Flitcroft record high score, so he bans him from future tournaments.

However, loyal Jean encourages Flitcroft to persevere, so he starts devising

ways to enter subsequent Opens under assumed names.

Without

question, Phantom is most entertaining when it revels in the subversive

farce of Flitcroft’s Open capers. His disguise as French golfer “Gerald Hoppy”

is a sequence worthy of Peter Sellars. (It even comes with a Clouseau

moustache.) However, Roberts somewhat loses his way, indulging in some painfully

maudlin family melodrama during the third act. Flitcroft was born to burst

pretensions, rather than be elevated to some kind of tragic hero.

It is one of the highest grossing Indian films of all-time and it was

partly shot in Ukraine, but apparently that didn’t mean much to the government of the “world’s

largest democracy” when Putin invaded. After all, shooting had already wrapped,

on a picture that ironically protests the brutality of British imperialism. In

this action epic, the British probably lose more soldiers than they did at

Bunker Hill. Such an incident would have surely led to a parliamentary inquiry,

especially since a regional governor precipitated the whole mess by abducting a

young girl. That just isn’t cricket, you know? Two legendary early Twentieth

Century revolutionaries form a fictional friendship and team-up against the

British in S.S. Rajaouli’s RRR (a.k.a. Rise Roar Revolt), which

has a special one-day return to American theaters this Wednesday.

Governor

Scott Buxton and his Lady Macbeth-esque wife Catherine happened to hear a young

Gond singer during their trip to Telangana, so they just figured they’d take

her with them as a souvenir. As the “shepherd” of the tribe, it is Komaram Bheem’s

sworn duty to find her and safely bring her back. To do so, he naturally falls

in with Delhi’s revolutionary circles. Unfortunately, his brother comes to the

attention of A. Rama Raju (better known as Alluri Sitarama Raju), who was then

a hard-charging Indian officer, but secretly harbored revolutionary ambitions.

While

chasing Bheem’s brother, Raju stops to rescue an endangered street urchin, with

the oblivious help of Bheem himself. Being men of action, a fast-friendship

blossoms between them, but when Bheem launches his rescue operation, it forces

Raju to make a series of soul-searching decisions.

Despite

the patriotic themes (critics would call RRR jingoistic if it were made

in America), the reason it traveled so well outside of the subcontinent is the

off-the-wall action. The sequences involving CGI-animals might even be a little

too off-the-wall, but perhaps they look better on a more spacious big screen.

Still, our introduction to Raju is quite a barn-burner and incidentally also a

good lesson in crowd control. Arguably, the whole thing morphs into a

super-hero movie during the climax, when they become invested with the powers

of Lord Rama, but it certainly makes for some wild spectacle.

You have to appreciate a celebrity chef who acknowledges the five-second

rule. Julia Child wasn’t above brushing off a little dirt from kitchen mishaps,

which was one of the reasons she was so fun to watch. For years, she was also

the original and only really notable TV chef. If she were alive today, she would

probably have her own streaming channel, but the magnitude of her success in

her time was still no can of corn. Julie Cohen & Betsy West chronicle Child’s

life and career in the documentary Julia, which airs tomorrow on CNN.

Before

she served dinner, Child served her country as a staffer for the OSS, Wild Bill

Donovan’s forerunner agency to the CIA. Her family insists she never did any spycraft,

but that still seems like a good idea for a fictional thriller. Regardless, she

met her future husband, Paul Cushing Child, when they were both posted to

Ceylon. Eventually, his career in the Foreign Service brought them to France,

where she met Simone Beck and started collaborating on Mastering the Art of

French Cooking, an unusually detailed cookbook, intended for American

readers.

Public

television was pretty grim in the early 1960s, but WGBH viewers appreciated how

she livened up a book review program, by demonstrating the proper technique for

making an omelet. As a result, they took a chance on a show of her own, The

French Chef. The best part of the doc gives a behind-the-scenes view of its

early, by-the-seat-of-its pants years. The production process might have been

an adventure, but the show was an immediate hit.

Everyone

gives Child credit for making PBS watchable, yet Public Broadcasting thought it

was time to put her out to pasture in the early 1980s, so she signed with Good

Morning America instead. It is clear throughout Julia that Child was

a shrewd capitalist. However, Cohen & West (whose RBG celebrated

Justice Ginsburg for having a kneejerk political record on the bench, rather than

a coherent judicial philosophy) do their best to transform Child into a

divisive figure, by celebrating her liberal activism.

This provincial Austro-Hungarian-era Czech town could relate to a lot of

college campuses today. Anti-Semitism is rife, often manifesting in “blood

libels.” Consequentially, when a bullying officer is murdered, the local

authorities are only too eager to arrest a Jewish man for the crime. However, Superintendent

Albert Mondl from Vienna is more concerned with evidence in Jiri Svoboda’s

Czech TV-produced Tormented Souls (a.k.a. A Soul to Redeem), which

airs on the Euro Channel.

Four

years ago, the “heroic” colonel nearly ran over Kacov’s son. When the accused

protested, the drunken officer gave him a lashing that left visible scars.

Inconveniently, Kacov’s happens to be a kosher butcher, so when someone slashes

the Colonel’s throat, the local police automatically arrest Kacov.

Of

course, as soon as Mondl arrives, he can tell they have no case. The killer

made a messy job of it, unlike a professional butcher’s work. Nobody likes it,

but Mondl releases Kacov and proceeds to run a real investigation. However, his

attention is diverted by Lea Stein, a gifted violinist, who remains deeply

traumatized by her mother’s supposed suicide.

Tormented

is

an effective portrayal of early Twentieth Century anti-Semitism and an

intriguing character study of the principled Mondl. However, screenwriter

Vladimir Korner fails to develop the potentially creepy revelation that all

three victims were involved in an ambiguously satanic secret society. Instead,

it rushes to a forced and unsatisfying conclusion.

The Jesuits aren’t what they used to be. These days, they are largely

aligned with Liberation Theology. Neto Niente’s nickname “The Jesuit” refers to

their hard-charging Seventeenth Century glory years. The gang enforcer could

definitely get Medieval on his targets, but he has been cooling his heels in

prison for years. When he finally gets released, there’s sure to be Hell to pay

in Alfonso Pined Ulloa’s There are No Saints, written by Paul Schrader,

which opens today in New York.

Ironically,

Niente did not commit the murder he was convicted of, so when the cop who

planted the evidence recanted on his deathbed, his lawyer, Carl Abrahams had

him released, free and clear. Of course, there are plenty of angry cops who

still want a piece of him. Niente would clear out, but he is worried about his

son, Julio. His wife Nadia has since married gun-running gangster Vincent Rice,

to help provide him a respectable cover. Even though it is not a real marriage,

Rice is still abusive—and lethally jealous when Nadia and the Jesuit have an assignation

for old times’ sake.

After

Rice murders Nadia, abducts Julio, and tries to kill Niente, but the Jesuit is

more resourceful than he anticipates. As we fully expect, Niente will chase

Rice down into Mexico, leaving a trail of dead associates in his wake. However,

Schrader’s grungy payback script is darker than you would expect. Arguably,

this is a familiar template for him. Basically, he does for the border town

milieu what Hardcore did for the underground LA porn scene and The

Yakuza did for the Japanese underworld. Yet, it still works okay, in an

unfussy, down-and-dirty kind of way.

History Channel's THEODORE ROOSEVELT is largely even-handed in its appraisal of the man and his domestic policy, but it largely ignores foreign policy. Isn't that just like the media? EPOCH TIMES exclusive review up here.

It wasn't exactly a caper that would impress Raffles. In 2005, a thief basically

walked out of Santiago’s Palace of Fine Arts with a Rodin sculpture on loan from

Paris. It was a crime of opportunity and according to the perpetrator, a work of

performance art. Somehow, almost all the talking heads sort of buy that in

Cristobal Valenzuela Berrios’s documentary, Stealing Rodin, which

premieres Friday on OVID.tv.

Luis

Emilio Onfray Fabres just happened to walk out of the museum with Rodin’s Torso

of Adele, during a reception, because nobody stopped him. To be fair, he

returned it in less than a day. Apparently, he was quite taken aback by the

resulting media furor and the potentially dire consequences for Chile’s

standing with major international art museums. The whole point was to get

people to appreciate it, in-a-heart-grows-fonder kind of way. Indeed, several

commentators compare his Rodin theft to that of the Mona Lisa, which made the

Da Vinci painting’s legend.

It

is true attendance for the Rodin exhibit subsequently sky-rocketed. However,

the film focuses solely on “L.E.O.F.’s” justifications. Nobody bothers to ask

if any museum guards were fired as a result of the theft or how much the Museum’s

insurance premiums were increased. The heart definitely grows fonder for lost

jobs and operating revenue.

Granted,

art thieves have developed a bit of a romantic reputation in films and novels,

but taking great works of art out of museums, where the public can see them, is

not progressive. In many ways, Stealing Rodin reflects what is wrong

with contemporary documentaries and journalism in general. It focuses on its

chosen “narrative” and never tracks the unintended consequences. (Honestly, we

need more economists making docs.)

Here is an odd-sounding couple: T.S. Eliot, the unofficial poet laureate of conservatism

and Father John Groser, a leader in the Anglican socialist movement. Yet, somehow,

they came together to bring to the screen Eliot’s passion-like verse play depicting

Archbishop Thomas Becket’s final days. It is not for mass-market tastes, but there

are great insights to be found when George Hoellering’s long unavailable Murder

in the Cathedral starts streaming this Thursday on OVID.tv.

Essentially,

Becket’s dispute with Henry II boiled down to how much the Church could render

unto Caesar while still maintaining its institutional integrity. Frankly, this

is not an academic debate. One could argue the current Pope has conceded far

more authority to the CCP in China than Becket could ever accept. He routinely

pledged his loyalty to his King and country, but he steadfastly insisted

nothing could supersede his vows to his God and Church.

Essentially,

the film consists of Henry’s inquisition, Backet’s departure and return from

exile, and his murder by four knights loyal to the King. That last part should

not be a spoiler. Even if you do not know the history, you should know how the

Peter O’Toole-Richard Burton film Becket ended. (If you don’t, it’s a

minor miracle you got past “Eliot’s verse play.”)

Hoellering’s approach to Eliot’s play is uncompromisingly faithful and rigorously

Spartan, with extensive passages for choruses, either speaking in turn or in

unison. Canterbury Cathedral looks cold and drafty, but also hallowed and holy.

Arguably, this might be the most authentically medieval-looking film that does

not wallow in the muck, mire, and pestilence.

In

fact, the austerity of Hoellering’s vision is partly why it is so arresting. Indeed,

the film reminds us that some of the most visually arresting films have had

religious themes. In terms of look and tone, Cathedral can easily sit

next to Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc and Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev. The three films would make an inspired but exhausting triple

feature.

It

is demanding material, but it is never dry, thanks in large measure to Groser’s

riveting performance. He carries the weight of the world with equal parts

compassion and conviction. He certainly looks more like a saint in the making

than Burton ever did. Eliot himself is perfectly cast as the voice the unseen

fourth “Tempter,” who tries to appeal to Becket’s vanity with the glory of martyrdom.

(Viewers should also be on the lookout for Leo McKern, the future Rumpole, who

plays the Third murderous Knight.)

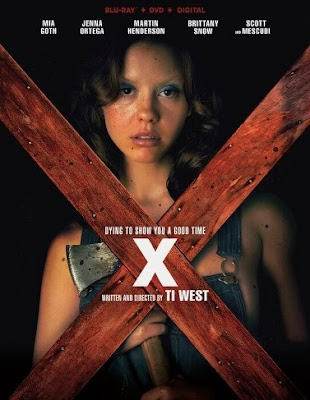

This is one of the few horror movies that makes Airbnb look like a good idea,

because it leaves behind a digital paper-trail, should guests disappear. It

also makes a good case for voting Libertarian, so a libertine, aspiring dirty-movie

king like Wayne Gilroy wouldn’t have to shoot his skin flick in East Jesus,

Texas, for reasons of economics and regulations. Alas, his hosts will be keenly

interested in what he and his cast get up to in Ti West’s X, which

releases today on DVD.

Maxine

Minx is convinced she is a star and Gilroy’s Farmer’s Daughter will be

the vehicle to launch her career. They will be filming in Howard and Pearl's rustic guest house, because it is so out-of-the-way. The script is exactly what you think it is,

but Gilroy hired director-cameraman RJ Nichols to make it look better than the

competition. Inevitably, there will be dissension in the group, making them easy pickings for Pearl,

a horny old prune, who resents the casts youthfulness and erotic gratification.

Alas, her loyal husband Howard can no longer satisfy her, but he can her dump

bodies in the pond, for the alligator to feast on.

Yes,

Ti West goes there, over and over. Obviously, there is a fair amount of sex,

but it really portrays sex-addiction and -obsession as lethally destructive

forces. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre influence is hard to miss, but the

addition of the alligator leads to some of the film’s best scenes. West uses

some striking overhead shots to tease viewers with its potential menace.

Despite

the televangelist who appears to preach non-stop on local television 24-7-365, X

does not play the card demonizing fundamentalist Christianity the way viewers

might expect, at least not yet (the promised prequel could be a different

story). Frankly, the first half is surprisingly restrained, but West skillfully

builds the tension.

West

is the sort of filmmaker who seems to run hot (In the Valley of Violence, The Sacrament, The Innkeepers) and cold (House of the Devil, The ABC’s of Death). Somehow, X manages to be half-and-half. Its richly

textured 1970s tackiness nicely celebrates the history and style of early

slashers. However, the smarminess of Pearl’s sexual jealousy gets tiresome. It

is the kind of thing that gets a ruckus response at a midnight screening, but quickly

loses its novelty during the course of a home viewing.

Still,

Brittany Snow and Scott Mescudi have the right genre-appropriate attitude and energy,

as Minx’s co-stars, Bobby-Lynne and Jackson Hole. James Gaylyn is also all

kinds of cool as the Sheriff stepping through the gore during the in media res

opening. However, the detachment of Mia Goth’s Minx (partly drug-induced) makes

her a hard presumed “final girl” to root for.

A cop like Ma Seok-do does not need to carry a gun, because just look at

him. It is just as well, since he is not supposed to pack any heat while in

Vietnam. According to local law, he is not supposed to be chasing any criminals

there either, but the “Beast Cop” from The Outlaws is always going to do

what he does best. A ruthless band of kidnappers preying on Korean tourists is

about to feel some pain in Lee Sang-yong’s The Roundup (a.k.a. The

Outlaws 2), which is now playing in New York.

While

technically a sequel, Roundup easily

stands on its own. For fans of the previous film, it looks like Ma’s

knees are holding up better now, but he is still just as huge. After taking

down the Garibong-dong street gang, he has earned a bit of slack, even when his

beat-downs make frontpage news. However, it might be convenient for the top

brass to send him to Vietnam to escort a criminal who turned himself in at the

consulate, while the controversy blows over.

Of

course, Ma has to wonder why a crook would voluntarily surrender himself in a

country without extradition. Fortunately, Ma has a knack for asking questions.

It turns out the thug is hiding from Kang Hae-sang, the leader of a vicious abduction

ring, who always killed his victims after receiving their ransom. His latest

abductee was the son of a mobbed-up, usurious finance chairman, who did not

take kindly to Kang’s methods. To find Kang, Ma can simply follow the dead

bodies of mercs hired to kill him.

Once

again, Don Lee (also billed as Ma Dong-seok) demonstrates massive screen

charisma as Det. Ma. He is big, but he has a charming facility for humor—honestly,

even more so than Schwarzenegger in his prime. Several times, Ma literally

punches bad guys through walls and it always looks totally believable.

Every few years, Hollywood gets proud of itself for releasing a woman-driven

action movie like Atomic Blonde, pretending they just invented something

revolutionary. Of course, it is nothing new or original to those of us who have

been digging Michelle Yeoh and Angela Mao films for years. With this action

heroine, maybe we can give Bollywood a few points for originality, but they

still have to get the job done. Agent Agni always completes her mission, but

the ride is a little rough in Razneesh Ghai’s Dhaakad, which is now

playing in New York.

As

a young girl, Agni’s parents were mysteriously assassinated, so she was adopted

by her future handler in the super-secret, off-the-books Indian intelligence

agency she now serves. Agni has been hot on the trail of a human trafficking ring

led by Rudraveer, who rose up from the coal fields of Bhopal through a maybe

not-so weird combination of class-warfare trade unionism, a cult of

personality, and brute force. He also had the brains of Rohini, a madam turned

master money-launderer.

Just

when Agni though she had them cornered, her operation turns to coal dust (that’s

a frequent metaphor in the film). As a result, she starts to suspect there is

probably a mole informing Rudraveer. Yet, despite of her standoffish nature,

Agni starts trusting her nebbish local contact, Fazal, and his wide-eyed little

daughter Zaira. Of course, that gives Rudraveer a weakness to exploit.

The

fight choreography in Dhaakad is often spectacular and frequently

surprisingly brutal. In fact, it is almost shocking how hard-edged the film is,

even by American standards (and especially for Bollywood). On top of that, Agni’s

wardrobe is some of Indian cinema’s most fetish-satisfying leatherware, since

Sunny Leone made her Bollywood debut.

Be

that as it may, Kangana Ranaut clearly trained like a demon to play Agni. Even though

she must have had lots of help from stunt performers, it is still a gruelingly

physical performance. Arjun Rampal is also huge on the screen and massively

sinister as Rudraveer. In terms of size, he seems to hulk up somewhere between

Godzilla and Salman Khan. However, Saswata Chatterjee is just too sleazy-acting

for figure like the handler.

State media only airs propaganda favorable to the regime in power, because that

is its only reason for being. However, for one brief night in 2002, the local

CCP-controlled TV station in Changchun broadcasted some contrary points of

view. They had been hacked. As a result, comic artist Daxiong was forced to

leave China, even though he was not involved. He was a Falun Gong (or Falun Dafa) practitioner,

just like the signal hijackers, so he faced similarly harsh reprisals.

Understandably, he had rather mixed feelings about the “hijacking,” but he came

to respect the hijackers’ motivations and sacrifices while designing the

animation of Jason Loftus’ documentary Eternal Spring, which screens as

part of the 2022 Human Rights Watch Film Festival.

If

the opening round-up scene were a live-action tracking shot rather than

animation, it would have film geeks screaming comparisons to Fincher and Paul

Thomas Anderson. It still will knock viewers’ socks off. Yet, it also serves an

important function, illustrating the ruthlessness of the police crackdown

following the broadcast signal intrusion.

In

more traditionally filmed scenes, Daxiong meets with a handful of survivors now

living abroad, for feedback on his rendering of the characters and the city of

Changchun at that time. Eternal Spring has garnered comparisons to Jonas

Poher Rasmussen’s Flee, but the animation Daxiong designs is much

more stylish and the true story Loftus helps tell is far more tense and

gripping. Flee looked perfectly fine, but clearly the animation

began and ended in a computer, whereas viewers can easily tell Eternal Spring started with Daxiong’s pen and paper.

There are several contemporary scenes featuring Daxiong

and the survivors, but the overwhelming majority of the documentary animates

the planning, execution, and aftermath of the signal intrusion. We come to care

about the figures involved, especially the working-class trucker appropriately

dubbed “Big Truck,” even though we know they will face unjust fates. Tellingly,

the one event the doc only mentions in passing is the trial itself, because why

bother? It held no suspense or uncertainty.

It isn't just the genocide of Muslim Uyghurs that Iran and other Mid East

regimes deliberately overlook to cozy up to Xi’s China. They also ignore the

genocidal crimes committed against Rohingya Muslims by the Myanmar military

junta, whom the CCP has embraced. Life is nearly impossible for the Rohingya in

their own country, even for Nyo Nyo. She has an apprenticeship with the Buddhist

Hla, but their relationship is often quite strained, as Snow Hnin Ei Hlaing

documents in Midwives, which screens as part of the 2022 Human Rights

Watch Film Festival.

Rakhine

state in Myanmar (a.k.a. Burma) is a powder keg. Racist mobs (sadly including

some Buddhist monks) regularly march through the district condemning Muslims

and those who protect them. Arguably, Hla and her husband are running a grave

risk by employing Nyo Nyo, but they to can be cruel and dismissive towards her.

Yet, she plays an essential role translating for Rohingya women, who can only

seek treatment at Hla’s clinic, due to ethnic-based travel restrictions.

Listening

to the virulence of the propaganda spewing on television broadcasts and during

street demonstrations is bracingly eye-opening. If this were regularly reported

on American nightly news broadcasts, Myanmar would be sanctioned back to the

stone age. It also should lead viewers to reserve judgement on Hla, even though

her behavior is sometimes troubling. On the other hand, it is easy to respect

Nyo Nyo, who becomes increasingly enterprising as the film progresses. In

defiance of Muslim teachings regarding interest-charging, she starts a

neighborhood saving-and-loan coop to empower her fellow Rohingya women.

Capitalism and freedom always go and grow together.

Mostly

Hnin Ei Hlaing maintains a micro focus on the two midwives, but macro events

regularly intrude on their lives. The film starts before the military coup,

when things were already bad, but continues afterward, with everyone fearing

for the worst. Yet, the doc makes great efforts to find cause for optimism, no

matter how modest.

If you're a character who gets a lot of flashbacks, chances are you did

some bad stuff in the past. Miami is flashback city for these five former high

school friends. The word “friend” is overstating matters, but they definitely

have some scandalous shared history that gets them blackmailed at the start of Ramon

Campos, Teresa Fernandez-Valdes, and Gema R. Neira’s Now & Then,

which premieres today on Apple TV+.

Twenty

years ago, entitled Alejandro died under complicated circumstances that will

take eight episodes of flashbacks to fully illuminate. An unrelated motorist

also met her demise that night. Whatever happened, five former friends got away

with it—then. Now, on the eve of their twenty-year reunion, an unknown

blackmailer is demanding $1,000,000 each. Again, they think they get away with

it when the blackmailer is murdered, even though the money is still missing,

but the subsequent investigation turns into agonizing water torture.

As

fate would have it, Sgt. Flora Neruda, the rookie detective on the case twenty

years ago is now a veteran handling the contemporary investigation. Of course,

she immediately links the two inquiries. She generates a lot of uncomfortable

heat, especially for Pedro Cruz, who is the Democrat candidate for Miami Dade

mayor, running on a platform of immigration liberalization (even though it is a

federal issue). Inconveniently, he borrowed his share of the ransom from his

campaign funds, which is highly illegal.

Sofia

Mendieta also had trouble raising the funds, so she stole it from her criminal

associate Bernie. To evade his thugs, she foists herself on her old flame, Marcos

Herrero, whose wealthy but controlling father “fixed” everything twenty years

ago. However, her presence is a little off-putting to his fiancée Isabel, but

she tries to be cool, until their carrying-on just gets too blatant.

N&T

is

all kinds of lurid and super-slick. In some ways, it is a throwback to the

trashy miniseries of the 1980s. Apple is billing it as a “bilingual” series,

but it is largely divorced from the culture and certainly the politics of Miami’s

Cuban, Venezuelan, and Brazilian communities. However, there is sex and

betrayal by the cigar-boat-load, so nobody is going to be bored by it.

It is character-driven science fiction that jealously guards its secrets. The character-driven part is nicely done. Epoch Times exclusive review of NIGHT SKY up here.

Harry Palmer did not jump out of airplanes with a Union Jack parachute and a

bottle of champagne. He was a grittier, grubbier kind of spy. Not much for grandstanding

and skeptical of authority, Palmer was a workaday, working-class agent. The new

dramatization of Len Deighton’s first novel initially remembers who Palmer was,

but than it forgets it. Unfortunately, most of the updating and liberties taken

are mistakes in John Hodges adaptation of The Ipcress File, which

premieres today on AMC+.

Initially,

Harry Palmer is more like Harry Lime, managing an ambitious black-market

operation throughout divided Berlin as a mere Corporal. Next comes the brig,

but Major Dalby from an off-the-books intelligence agency offers him a furlough

in exchange for contacting a target code-named “Housemartin.” Palmer once did

business with the mercenary-smuggler. However, Housemartin has advanced to some

pretty serious business, including allegedly kidnapping Prof. Radcliffe, a

missing atomic scientist. So far, so Deighton.

Unfortunately,

things change when Palmer and fellow agent Jean Courtney are to dispatched to

the South Pacific, to observe a nuclear test that might be related to Dawson’s

research. Here the plot radically diverges from the novel and the classic

Michael Caine film. For one thing, the ultimate villain is no longer the original

villain. Instead, he is just be played by Col. Stok, who was something like Le

Carre’s “Karla” in later Harry Palmer novels. The Soviets are not really the

baddies anymore, just impish rivals. Who are the bad guys now? Us, of course—the

Americans trying to win the Cold War. How dare us.

This

isn’t a complaint based on wounded national pride. Hodge loses thread of what Ipcress

is, turning it into a half-baked JFK assassination conspiracy thriller, with

Palmer being set up as an Oswald-style patsy. We have seen far too many of

these exploitative yarns. It also diverges from the elegant simplicity and mordant

humor of the classic ending. Palmer belongs in a dark and dingy warehouse, not a

big macro-geopolitical thriller that could pass for a cross between Oliver

Stone’s JFK and Day of the Jackal.

If there is one thing we get from movies, if we use them as our counselors

and therapists, it is getting out of the apartment is always a healthy part of

the recovery process. Unfortunately, Cordelia Russell apparently hasn’t watched

a lot of films, even though she is an actress. (She certainly hasn’t seen Repulsion.)

Nevertheless, an upstairs neighbor tries to reach out for her, but his motives

are a big question mark in Adrian Shergold’s Cordelia, which releases

Friday in theaters and on-demand.

The

withdrawn Russell is still suffering from acute post-traumatic stress, but

somehow, she can still perform in a stage production of King Lear (as

her namesake, ironically). Fortunately, she lives with her identical twin Caroline,

who handles most of the practical business of life. Then one afternoon, Frank

Ryan, the professional cellist renting the flat above her, approaches Russell

at a coffee shop.

It

turns out he is attracted to Russell, but it is really probably Caroline who he

probably saw on the streets. Regardless, he does his best to charm her, even

convincing Russell to accompany him on the Metro, which brings back painful

memories for her. However, as he continues to court the twin, things start to

get weird.

Eventually,

Shergold and co-screenwriter Antonia Campbell-Hughes (who also stars as both

Russell sisters) try to raise all sorts of is-she-or-isn’t-she and is-he-or-isn’t-he

doubts about the main characters. It is a mixed bag in terms of its effectiveness

playing minds games, but it is a bit troubling to learn Russell is a survivor

of the 7/7 terrorist attack. Using a very real tragedy like 9/11 or 7/7 is a

risky proposition that can easily descend into exploitation. Cordelia is

not sleazy in the way it addresses the attack, but it is a bit jarring

nonetheless.

History students should appreciate found footage horror, because it is told

entirely through supposed primary sources—as primary (and often primal) as it

gets. It feels real, because it looks like it was recorded as it happened. Of

course, the better ones require extensive planning and preparation, while the

worst give the subgenre a bad name. Some of the leading filmmakers associated

with the grungy style reflect on its meaning and development in Sarah Appleton

& Phillip Escott’s The Found Footage Phenomenon, which premieres

Thursday on Shudder.

To

their credit, nobody interviewed in Phenomenon suggests found footage

horror started with Blair Witch. Instead, they point to the epistolary

style of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula and Orson Welles in/famous War

of the Worlds radio broadcast. It is so Wellesian that he innovated a

super-cheap and convincing method of story-telling, but left it to others to

exploit it commercially. Some also point to Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom,

but the Blair Witch Project and Ruggero Deodato’s notorious Cannibal

Holocaust were really the first films that had marketing campaigns designed

to convince people what transpires on-screen happened for real.

Of

course, everyone more or less concedes all the found footage films that

followed Blair Witch represent a wildly mixed bag. To often, they

feature disturbing levels of violence. Filmmakers can justify it any way they

like, but it doesn’t make the ultra-realistic-appearing brutality any easier to

watch. That is why clever and inventive found footage, like the Paz Brothers’ JeruZalem

and What We Do in the Shadows (both of which get their due) are so

fun and different.

Appleton

& Escott talk to just about everyone they should, including Deodato,

Eduardo Sanchez (co-director of Blair Witch), Doron and Yoav Paz, Patrick

Brice (director of Creep), Rob Savage (Host), Steven DeGennaro (Found Footage 3D), and Oren Peli (of the Paranormal Activity franchise,

probably still the reigning champion of the found footage box-office).

It is not that this is a great movie, but its time is now. Violent crime is

way up and progressive DA’s increasingly refuse to prosecute criminals. Inevitably,

we are going to see a bounty of vigilante films to supply the need cathartic justice.

William Duncan represents a lot of frustrated fathers and family members, when

the cops and the system fail him in screenwriter-director Jared Cohn’s Vendetta,

which releases tomorrow through Redbox.

Danny

Fetter is about to be initiated into his father’s crime syndicate, based in

small town Eatonton, Georgia, by gunning down the daughter of William Duncan. She

was actually a bad random selection, because her father picked up a lot of

skills in Iraq and Afghanistan. The DA is willing to let Fetter plead to a weapons

charge and a parole violation, since Duncan did not actually see him pull the

trigger. He just tackled Fetter trying to escape.

Instead,

Duncan bludgeons the killer to death with a baseball bat. Old man Donnie Fetter

and his junkie son Rory think they should be the only ones getting away with

murder, so they come after Duncan and his wife. Meanwhile, the super-helpful

Detective Chen keeps lecturing Duncan on the need to keep the peace.

There

is a reason why the original Dirty Harry became a sensation when it

first released and the sociopolitical circumstances are similar today. However,

Dirty Harry was also an excellent film, which Vendetta is not. Yet, it

is zeitgeisty, probably more than Cohn intended or realized, because it taps

into deep, widely-held anxieties and frustrations.

In

light of recent news, it is sad to see Bruce Willis portraying Donnie Fetter. Honestly,

this isn’t the role his fans would probably choose for him go out on. (Again, American Siege was not a great film either, but there is a poignancy to Willis’s

performance that arguably redeems it.)

Being in a Yakuza clan is sort of like the licensing business. Your territories

are everything. Seigou Kunigami thought his gang had their Okinawa territories

sown up when they made a pact with their main rival. However, after the

handover of Okinawa back to Japan, the so-called “Yamato” gangs assume they can

expand their business there. Inevitably, gang war breaks out in Sadao Nakajima’s

Terror of Yakuza (a.k.a. Okinawa Yakuza War) which screens

during the Japan Society’s Visions of Okinawa film series.

Hideo

Nakazato went to prison for killing to secure the gang’s prominence. Now that he

is out, he just wants to make some money. However, he finds his old comrade Kunigami,

the clan leader in his absence, is spoiling for a fight, especially with the

Japanese, but also with their more accommodating rivals. His temper is so

violently unstable, the various clan leaders might be wiling to make Nakazato a

deal. He also might have two new recruits, islanders like Nakazato, who would

be perfect for the dirty work.

Nakajima

shot Terror on the streets of Okinawa City, at a time when much of the

local industry either supported the U.S. military base or catered to their

vices. It is easy to imagine Manila looked a lot like this during the early

wild and wooly Marcos years. This distinctive backdrop adds something extra to

the Yakuza beatdowns, but it still has the classic genre elements fans enjoy,

like a massively funky soundtrack and Sonny Chiba at his most ferocious, as

Kunigami.

Technically,

the ultra-steely Hiroki Matsukata is the star, hard-staring his way through the

picture as grizzled Nakazato. Yet, Chiba is so crazy jumping on tables and

literally tearing up the town, he still imprints his brand all over Terror—even

though Matsuka is still really terrific, in the lead. This is definitely a testosterone-driven

film, with men often behaving quite horribly, but Emi Shindo adds a note of

tragic grace as Nakazato’s long-suffering wife, Terumi.

In his youth, Czech novelist Josef Skvorecky was an ardent jazz musician, but

playing music from America was a dangerous proposition. However, when bassist

Herbert Ward temporarily defected, Skvorecky and his bandmates capitalized (so

to speak) on Ward’s “anti-imperialist” credentials to openly play their music.

James Bulwer is transparently based on Ward, but Danny Smiricky’s friends will

not enjoy much protection from their association with him in Andrea Sedlackova’s

The Sound of Freedom, based on Skvorecky’s “Little Mata Hari of Prague,”

which airs on the Euro Channel.

Of

his band, Smiricky was always the least interested in politics. Nevertheless,

he always carried guilt over the misfortunes suffered by his bandmates and

their social circle. Frankly, he never really understood why he was spared the

worst of it, because guilt and innocence were meaningless under Communism. He

might have an opportunity to discover why, when Kunovsky, a former secret

policeman, offers to sell him his long-lost file.

Back

then (predating the Prague Spring), Smiricky just wanted to play and maybe

pursue a relationship with Geraldine Brandejsova. She would be bad news anyway,

since her mother is British. To make matters worse, Brandejsova has a friend in

the American embassy, for whom she acts as a go-between with an activist

priest. Kunovsky and his slimy boss have been assigned to build a case against

Smiricky’s band. Unfortunately, their vocalist Marcela Razumowska is the

obvious weak point for them to pressure. She tries to protect her friends, even

breaking up with Richard Kambala, the trombonist-leader, but the life of her

imprisoned brother depends on her providing incriminating evidence.

Although

Sound of Freedom was produced for Czech television, it is remarkably

mature and achingly tragic. It also has a nice swing-era-appropriate soundtrack

that includes a number of arrangements by the great Emil Viklicky. There is

also a laughably strident propaganda blues for Bulwer, very much like those Ward

warbled, while backed by Skvorecky.

It is almost unfair. A lot of musicians who never play jazz (maybe because

it is a demanding art form that never pays as well as pop), are keen to perform

at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, because it is a great time,

with delicious food. Of course, NOLA is always welcoming, so consequently many

of the biggest names in a wide array of musical styles have performed at the

festival. Many of those appreciative artists pay tribute to the annual

institution in Frank Marshall & Ryan Suffern’s documentary Jazz Fest: A

New Orleans Story, which opens today in New York and Los Angeles.

Marshall

& Suffern do not exactly present a history of the festival, because they

only cover a handful of significant events from Jazz Fest’s past, logically

starting with its creation. George Wein, the founder of the Newport Jazz

Festival, was approached to start something similar in New Orleans, but he begged

off until segregation officially ended in southern states. Logically, Louis

Armstrong played the inaugural fest, but we see little footage of him at the

Fest. Frustratingly, there is even less of the rest of NOLA’s Holy Trinity of

musicians: Fats Domino and Al Hirt.

At

least one undisputed New Orleans legend gets her just due from Marshall &

Suffern. That would be Irma Thomas, who we hear rocking “Jock-o-mo.” (The credits

misidentify it as “Iko Iko,” which is a sore point for the composer’s son,

Davell Crawford, whom the audience also gets to hear from musically and more

extensively in interview segments regarding Katrina.)

It

is quite impressive that Katrina did not derail Jazz Fest. In fact, it provides

some of the documentary’s most uplifting moments. Yet, perhaps tellingly, Covid

did—for two years. Throughout it all, Festival Director Quint Davis was there,

so he provides plenty of commentary and reminiscences.

Marshall

& Suffern keep the film moving along and well-stocked with famous names.

Most viewers probably aren’t looking to a Jazz Fest doc to hear Pitbull or

Jimmy Buffet, even though the latter’s long association with the festival and

the city of New Orleans justifies his inclusion. Frankly, Marshall &

Suffern’s a-little-of-this-a-little-of-that cafeteria approach works best when

presenting fresh artists exploring under-represented genres, like the Rising

Star Fife and Drum Band and Dwayne Dopsie & the Zydeco Hellraisers, who do

just that, in an infectiously musical way.

Cora Seabourne is finally acting on her ambition to become a renowned

paleontologist, or maybe rather a cryptozoologist. Up until recently, she has

only been a case study in the folly of the Victorian era’s restrictive gender

roles and arranged marriages. However, she is about to celebrate her new-found

freedom by investigating reports of a sea creature in Apple TV+’s six-episode The

Essex Serpent, adapted by Anna Symon from Sarah Perry’s novel.

In

addition to being an early feminist, Seabourne is also ahead of her time

refusing extraordinary measures to save her dying husband. Frankly, in his

case, she arguably rebuffed some rather ordinary measures as well. Regardless,

she is now rich and single, which certainly interests her abusive late husband’s

physician, Dr. Luke Garrett. In fact, he even follows her to Essex where

Seabourne is holidaying, to investigate the local sea monster, blamed for a

series of woes that have befallen the community.

Naturally,

Seabourne hopes to discover some sort of cryptid. However, the local vicar,

Will Ransome, assumes it is some form of mass hysteria, like the Salem

witchcraft paranoia. It would indeed appear the vicar is the only voice of

reason in town, but the other pastor, not so much. Inevitably, Seabourne’s

insensitivity rubs the locals the wrong way. She also conveniently refuses to

notice the torch-carrying of both Dr. Garrett and her Marxist maid, Martha.

However, she is keenly aware of the scandalous romantic tension building

between her and the married Ransome.

Symon’s

adaptation is frustrating for many reasons. First and foremost, it isn’t even

sufficiently interested in the titular Essex Serpent to treat it with any sort

of suspenseful ambiguity. Instead, it is simply used as a crude, didactic

metaphor. Even still, there is no real resolution regarding the villagers’

curse-like misfortunes they attribute to it.

Indeed,

after spinning its wheels over several episodes worth of over-heated melodrama,

the series just ends with a hum-drum thud. It doesn’t pay off and the trip

getting there is not particularly interesting.

Yet,

Tim Hiddleston is still quite compelling as the conflicted and guilt-wracked

Ransome. Ironically, his performance probably still counts as one of the more sympathetic

clergy characters recently seen in streaming series, sort of like a chaste

version of Richard Chamberlain in The Thorn Birds.

Arguably, it is more of a thriller with sf elements than a horror story, but the premise is pretty

horrifying for parents. Charlie McGee did not just inherit a resemblance to her

parents. She also has their “shine.” That was the whole idea for the shadowy government

contractor DSI (aren’t they always shadowy), when they experimented on Andy

McGee and his wife Vicky Tomlinson-McGee. Little Charlie’s resulting powers are

getting harder for her to keep in check at the start of Keith Thomas’s Blumhouse-produced

remake of Firestarter, which opens today (and starts streaming on

Peacock).

The

McGees know their daughter could be so dangerously powerful, she could never

have a normal life if DSI and the “deep state” ever got their hands on her. They

live under assumed names and completely off the net, but bullied Charlie is

starting to attract unwanted attention, especially when her temper ignites real fires.

Captain

Hollister knows she is still out there and suspects the potential of her

developing X-Men-like abilities. Hollister also has just the man to track down

the McGees. John Rainbird understands them all too well. He too has the power

to get inside people’s heads, perhaps even better than Tomlinson-McGee and can

withstand McGee’s power to “push” mental images and suggestions, at least to an

extent. Unfortunately, that “pushing” is starting to take a toll on McGee’s

health.

Scott

Teems’ screenplay adaptation of Stephen King’s novel very much follows the structure

of the 1984 film, which was pretty faithful to the book. It definitely leans

into the father-daughter relationship, because that is the whole point of the

story (in all its incarnations). However, the family-versus-agents conflict is

familiar, to the point of staleness. Horror fans might know John Carpenter was

originally in-line to direct the ’84 film, but he lost the gig when The

Thing bombed (hard to believe, since it’s now regarded as a classic). Sadly,

Blumhouse did not hire him to direct this time around, but he did contribute to

the score. You can probably best hear his influence during the tense,

confrontational third act.

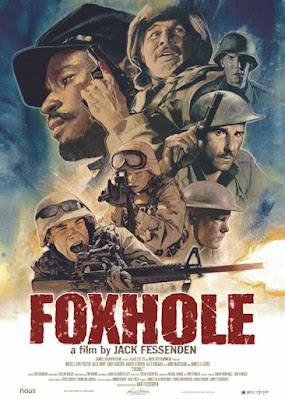

The hardware and uniforms change, but the fog of war remains. This film also

suggests the young people asks to fight wars are in many ways quite similar—identical

in fact. The same cast plays out life-and-death encounters from the Civil War,

WWI and Iraq Wars during Jack Fessenden’s Foxhole, which opens tomorrow

in New York.

Jackson

is a Buffalo Soldier who basically crashed a small Union company’s foxhole, after

a Confederate officer wounded him, perhaps mortally. Conrad and old grizzled

Wilson believe some of the men should carry him to the distant field hospital,

but Clark (presumably hailing from border state hill country) argues Jackson

would probably die on the journey and the medics maybe wouldn’t take him

anyway.

There

is a similar ethical dilemma for the company when then film advances to WWI. They

have captured a German soldier in their trench at an inconvenient time, so

their sergeant wants to kill him and be done with it. Again, Wilson objects and

so does Jackson, a soldier from a black regiment, who is somewhat more readily

accepted by the white doughboys.

Easily,

the best of the three stories is the conclusion in Iraq—but at least a country

mile. By now, Jackson is the leader of the squad. There is no internal

dissension within the group and they will face no ethical dilemmas. Instead,

they will merely try to survive, without leaving any men behind (including Gale,

a new addition to the platoon), when they are separated from their convoy and

ambushed by insurgents with an RPG launcher.

Of

the three installments, the dialogue of the Iraq section sounds the most like

the military talk I’ve heard (from family). It also forgoes the anti-war moralizing,

instead portraying the courage and camaraderie of the U.S. military. It actually

makes Foxhole more effective as anti-war critique, because it shows two sides

to the combat experience (and the dangers and difficulties they entail), while

inviting sympathy for the men and women in uniform.

It

is also the tensest and most skillfully executed. In this case, the definition

of foxhole is expanded to include the Humvee the soldiers are dug into.

Fessenden (son of Larry, on-board as a producer) uses the blinding sand to

narrow the audience’s field of vision, creating an uneasy feeling that a fatal

shot could come from anywhere, at any time.

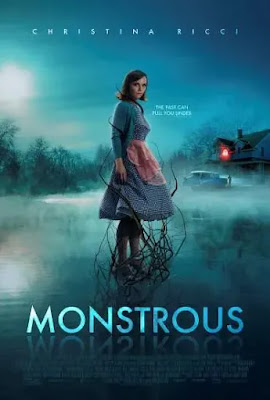

Horror movies hate the 1950s. It was a time of stability and economic growth.

What a nightmare. Thank goodness the last few years have been nothing like

that. Unfortunately, that is the decade Laura Butler is living in, or at least a

stylized version of it. The going was already tough for her, after she left her

abusive husband, with their withdrawn son, Cody. Then she starts to suspect a

mysterious supernatural something is out to get her son in Chris Sivertson’s Monstrous,

which releases this Friday in theaters and on-demand.

It

is supposed to be the 1950s, but there is something too conspicuously off for

viewers to accept the world as it is presented. Butler’s sun dresses are a

little too perfect and her forced cheer is a little too desperate. In the

aftermath of her husband’s latest violent episode, Butler fled with Cody, starting

over in a vaguely Southern small town. Somehow, she lined up a new job, new

house, and a new school with remarkable efficiency. Their rental is even furnished,

but one of the books on the shelf looks like Inflation: A Worldwide Disaster,

by Irving Friedman, published in the early 1970s. Don’t blame the art

department for that. Blame Sivertson, who let my attention wander.

Initially,

Cody was terrified of lady-creature in the nearby lake, but soon he is talking

to her like an old imaginary friend. Logically,

that starts to terrify Butler. As Cody becomes even more anti-social, she

become increasingly distraught.

Honestly,

it gets tiresome to always be so far ahead of a film. Monstrous largely

feels like parts of Miss Meadows re-edited into Jacob’s Ladder

(and Miss Meadows wasn’t so great to begin with). These days it is

streaming series like Severance and Shining Girls that deliver genuine

surprises, while far too many films merely recycle elements.

Actor M.E. Clifton James helped pull off one of the most famous deceptions of

WWII, by serving as Gen. Montgomery’s double. Glyndwr Michael was at the center

of an even more audacious counter-intelligence operation, but he was already

dead at the time. For the sake of all the young servicemen slated for the

invasion of Sicily, the officers and staff at the British Admiralty’s

intelligence division launch a desperate mission to convince German the landing

will come in Greece. Their efforts are chronicled in John Madden’s Operation

Mincemeat, which premieres today on Netflix.

The

film starts at zero-hour, when the Mincemeat staff can do nothing more but

prey, which they solemnly do. It is actually one of the most effective and

powerful in media res film openings in recent years. A few short months

earlier, Lt. Commander Ewen Montagu and Squadron Leader Charles Cholmondely

were assigned to Operation Mincemeat, designed to plant false intelligence to

draw Hitler’s forces away from Sicily. Although their commanding officer, Rear Admiral

John Godfrey was skeptical, they were convinced they needed to tie their

fabricated intel to an actual body, for the Germans to ever believe it. Godfrey’s

aide, Ian Fleming happened to agree with them and ultimately so did Churchill.

Although

the historically-based characters are rarely directly in harm’s way from the

Axis, there is the tension of a ticking clock driving the narrative. It is also

surprisingly compelling to watch the two officers and their civilian assistants

become emotionally involved in the fictitious lives they create for the

invented “Maj. William Martin” and his faithful girlfriend, like authors developing

feelings for their fictional characters.

Despite

the cerebral nature of the story, Madden builds a good deal of suspense. Ironically,

a lot of it comes from the number of Spanish officials who tried to act

in good conscience, in accordance with their ostensive neutrality. It took a

lot of sly machinations on the part of the local British consul (nicely played

by Alex Jennings) to appeal to their fascist inclinations.

On

the other hand, there is a distracting minor subplot ginning up paranoia over

suspicion Montagu’s brother Ivor was a Soviet spy, which he was indeed, but

apparently only briefly and with little tangible results. The portrayal of Churchill

is a bit of a caricature, but it also shows that he was nobody’s fool. However,

the film does a great job conveying tactics, strategy, and the general wartime

environment.

A.K. Tolstoy (second cousin of Leo) could have been one of the great horror

writers of his era, but when The Vampire bombed, he held off publishing

the next three supernatural stories he had lined up. Eventually, Family of

the Vourdalak became a minor classic that horror fans well-remember as one

of the tales adapted in Mario Bava’s anthology film, Black Sabbath. Now,

the Eastern European vampire is transplanted to Argentina in Santiago Fernangez

Calvete’s A Taste of Blood, which releases today on VOD.

Natalia

always chafed under the controlling thumb of her father Aguirre, but she is

about to discover why he is so strict. One night, she sneaks out to meet her

boyfriend Alexis (who really isn’t such a bad chap), but instead, she encounters

a stranger who claims to be a distant relative. Then he tries to kill her.

Fortunately, Alexis safely sees her home, where her father finally levels with

the entire family.

Aguirre

was adopted into a wealthy Slovenian émigré family, who had long been plagued

by Vourdalaks. Essentially, the Eastern European vampires are like undead

family annihilators, who particularly crave the blood of relatives and loved

ones. Aguirre decides to hunt down the latest Vourdalak, giving strict instructions

not be let back into the house before sunrise, because Vourdalaks cannot endure

sunrise. Yet, he turns up like clockwork, right before dawn, demanding they

open the doors, so he can crash.

Taste

is

a great looking horror film, thanks to cinematographer Manuel Rebella’s

striking use of light and darkness, but it sounds awful, because of the almost

random mixture of English dubbing with subtitled Spanish. Entire conversations

alternate between the two languages, for no reason, as far as viewers can tell.