If we let the CCP blatantly violate the

Sino-British Joint Declaration, openly turn Hong Kong into a police state, and

engage in hostile militarism throughout the South China Sea, maybe they will be

satisfied and start acting nice. After all, appeasement was a smashing success

when Hitler was given the Sudetenland, right? Actually, it was Neville Chamberlain’s

agreement that gave appeasement the bad name it deserves. Young British foreign

office bureaucrat Hugh Legat sees that infamous history unfold as an aide to

Chamberlain in Christian Schwochow’s Munich: The Edge of War, based on

Robert Harris’s novel, which opens today in New York, in advance of its January

21st premiere on Netflix.

Initially, Legat is more concerned with helping

Chamberlain prevent a European war than resolving the Cold War brewing between

him and his wife. It is really bad timing when he is attached to the Prime Minister’s

Munich delegation and also quite a surprise. It turns out Paul von Hartman, a

German government interpreter, pulled some strings with his military contacts

to request Legat’s presence. They were friends at Oxford, but had a falling out

over Hitler. At the time, von Hartman was an enthusiastic supporter, but now

that he knows the Fuhrer’s true intentions, he is profoundly alarmed.

Von Hartman believes elements in the military

will turn against Hitler Valkyrie-style if the British hold firm on their

commitments to Czechoslovakia. He also has a damning document that spells out Hitler’s

expansionist military plans in detail. He needs Legat to help him convince Chamberlain,

but even if his old friend agrees to help, it is highly questionable whether

the war-averse PM will listen.

Ben Powers’ adaptation of Harris is a really

smart thriller of espionage, politics, and bureaucratic in-fighting. However,

some of its implications are highly debatable. Mild Spoiler: Edge ultimately

presents an extremely revisionist defense of Chamberlain, arguing he bought

time with his non-agreement for England to rebuild its military. Yet, on the

other hand, it also posits a potential resistance to Hitler that was undercut

by Chamberlain’s appeasement and obliquely implies Hitler’s also needed time to

steel the resolve of the German people.

In any event, Schwochow (who has previously

helmed sensitive historical dramas, like The German Lesson, West, and The Tower) mines a good deal of suspense from the brainy material and maintains

even more tension regarding the fates of Legat and von Hartman. George Mackay

and Jannis Niewohner nicely humanize the cerebral main characters and portray

their complicated friendship with surprising poignancy down the stretch.

Wednesday morning, Hong Kong Cantopop star, democracy activist, and LGBTQ advocate Denise

Ho was arrested, along with five independent journalists with Stand News, where

she was once a board member. Her standing as one of Hong Kong’s most prominent

out-and-proud celebrities was not an unfortunate drawback for the CCP’s

quislings. It was a bonus. All human rights, press advocacy, and LGBTQ

organizations must speak out against her unjust arrest and that of the five

Stand News journalists. It is also worth noting the CCP did this just over a

month before hosting the 2022 Winter Olympics. The timing shows total, contemptuous

disrespect for the IOC, but the CCP obviously considers them bought and paid

for—and no doubt they are right about that. In light of Ho’s arrest, here is a

repost of her documentary profile from last year:

It is hard to hold back the tears watching Cantopop

idol Denise Ho and her fellow democracy activists in this film. Not just

because they are inspiring—although that is certainly true—but because the sense

of hope it documents was dealt such a harsh setback yesterday. As of today, 7.4

million Hong Kongers are no longer free and we let it happen, because we were more

preoccupied with Trump’s tweets and our own grievances. Democracy died not in darkness,

but the plain daylight of our disinterest. Viewers get a sense of the Hong Kong

that was potentially lost in Sue Williams’ Denise Ho: Becoming the Song.

Denise Ho is everything the media usually celebrates.

She is an immigrant, who moved to Canada with her family in the late 1980s, only

to return to Hong Kong, to pursue a career in music. She was the protégé of

Anita Mui, who was widely dubbed the HK Madonna for her sexually empowering stage

persona. Ho also became the second notable Cantopop celebrity to come out of

the closet, following the example of her close friend, Anthony Wong Yiu-ming.

So, what was it about the Lesbian artist that was so incompatible with the

values of Western corporations like Lancome that they dropped their sponsorship

deals? She joined the 2014 Umbrella protests for greater democratic governance

in Hong Kong.

Filming in the wake of the 2019 Extradition

protests, Williams follows Ho as she takes a more DIY approach to touring. The

star who used to perform in stadiums across Mainland China now books smaller,

more intimate clubs in Hong Kong and around the world, for the HK diaspora. Of

course, for Ho the money is not important. If anything, she has forged a closer

connection with her fans.

If an episode of South Park that satirizes the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was conspicuously excluded

from an American streamer’s Hong Kong site, Trey Parker and Matt Stone would skewer

them for it. However, Disney+ did exactly that when it censored the episode of The

Simpsons wherein Homer Simpson visited Beijing for its HK customers.

According to google, there has been no response from Matt Groening yet. If you

live in Hong Kong, you can’t watch “Goo Goo Gai Pan” (S16 E12), but the rest of

us still can, for now.

Homer

has an awkward relationship with his sister-in-law Selma Bouvier, but when she

enters menopause, he agrees to pretend to be her husband, to facilitate her

Chinese adoption. Naturally, their romantic chemistry is a bit dubious,

attracting the suspicions of Madame Wu, the chief adoption bureaucrat (played

by Lucy Liu).

This

being The Simpsons, there are plenty of slams on America (mostly easy groaners). However, writer

Dana Gould also aimed a number of clever barbs at the CCP. The one most likely

to offend the CCP would be the briefly seen Tiananmen Square Monument reading: “on

this site, in 1989, nothing happened.” So, Disney+ is literally self-censoring

a joke about the Communist Party censoring history. How sad is that? Especially

since it shortly preceded the removal of Tiananmen Square memorials across Hong

Kong, including the notorious dismantling of the Pillar of Shame statue at the University

of Hong Kong.

His X-Men/Tomorrow People superpowers are in Andrew Cooper’s DNA.

Apparently, so is stupidity. When Cooper submits his DNA test to the

government, he inadvertently alerts a super-secret agency to his existence.

Supposedly, they want to train him, but we know what that really means in

Martin Grof’s Sensation, which releases Friday on VOD.

Actually,

Cooper only thinks it was the DNA test, but we know from the makes-no-sense

prologue creepy Dr. Daniel Marinus was on to him from the start. Regardless, Cooper

is whisked off to a Hogwarts from Hell to be trained to use his psychic powers.

Something is really wrong about the place. They also claim to be holding his mother

at an undisclosed location, for her own safety, of course. However, whenever he

manages to reach her on the phone, she warns him to get the heck out.

Grof

and co-screenwriter Magdalena Drahovska try to combine parts of Inception and

parts of The X-Men, but only the worst parts. Frankly, this is the kind

of film that looks like a major cast-member died during the production and had

to be edited out as best as possible. As a result, none of the head-tripping

spectacle makes any sense without a coherent sense of logic to underpin it all.

It was a powerful comic book tag-teaming, but it was completely

uncoordinated. In 1940, Jack Kirby and Joe Simon created Captain America (first

comic book appearance March 1941) to fight Nazis. That same year, DC produced a

special issue of Look Magazine, featuring Superman beating the heck out

of Hitler. Those were the days. In many ways, it was the big comic publishers’

finest hour and a good example of their “friendly rivalry.” Directors Don Argott

& Sheena M. Joyce chronicle the competition and occasional cooperation

between Marvel and DC in the 10-mini-episode Slugfest, produced by the

Russo Brothers, which is now streaming on Roku Channel.

Slugfest, based on the non-fiction

book of the same title by Reed Tucker (who also appears as a talking head) was

greenlighted for Quibi, but the bite-sized streaming service folded before it

could premiere, so here it is now. The six-to-eight-minute installments are

punchy, but together they do not tell a cohesive narrative.

Regardless,

the first installment, “Nazis are Bad,” is easily the best. You have to give

Simon and Kirby credit for taking on Hitler and the National Socialists. Cap

was a hit, but he was not universally popular. In fact, Mayor Fiorello La

Guardia dispatched police guards to protect Timely Comics (as Marvel was then

known) from violent Bund protesters. What would Kirby and Simon think to see

the current management of their old company desperately currying favor with a

CCP regime currently conducting a campaign of genocide in Xinjiang, just to get

Chinese release dates for their movies.

In

contrast, “Halloween Hero” is a fun footnote explaining how the first

unofficial Marvel-DC crossover story was hatched by a group of writers and

artists for both companies. Throughout the series, Argott and Joyce stage the

sort of quirky reenactments they used in Framing John DeLorean. The most

colorful is Ray Wise, slyly chomping on his cigar as the older Jack Kirby in “Funky

Flashman,” which chronicles the artist’s departure from Marvel to

DC, where he infamously mocked his old boss Stan Lee.

“Reverend

Billingsley” plays up the 1970s trippiness of Doctor Strange, which does not

have much to do with DC (and the whole Age of Aquarius vibe of the mini-sode gets tiresome). “Superman

vs. Spiderman” is a cool look at the crossover fans always wanted, but the two

companies never thought they could pull off (with an appearance from Ron

Perlman, as a bonus). Likewise, “Cancelled Cavalcade” is a fascinating

chronicle of the dramatic 1978 “DC Explosion” of titles and the sharp

contraction that soon followed.

“Kill

Robin” and “A World without Superman” both present solidly entertaining (and

weirdly nostalgic) pop culture histories of the murder of the second Robin and

the hyped-up “death of Superman,” which of course, it wasn’t. “Send in the

Clones” tries to do the same for Spiderman clone storyline, but it won’t have

as much traction for casual comics fans. However, the series ends with what

could be its second-best episode, “Just Imagine,” a tribute to Stan Lee, with

an emphasis on his once in a lifetime stint at DC, reimagining their signature

characters, the Stan Lee way.

Our juvenile hero is a chimney sweep, but this is not a cute, upbeat

musical, like Mary Poppins. It is dystopian anime. Apparently, Chimney

Town was conceived as a utopia, but it turned into a dystopia, as utopias

necessarily always do. Yet, earnest young Lubicchi just might save his society

from its fears and ignorance in Yusuke Hirota’s Poupelle of Chimney Town,

produced by Studio 4ºC, which opens in limited release this Thursday, for Oscar

qualification.

Poor

Lubicchi must constantly sweep the smokestacks belching smoke over his

steampunky city, because he is the sole support of his wheelchair-bound mother,

since the death of his beloved father. When he was alive, Bruno used to tell

stories about stars in the sky and other lands beyond the sea, but everyone assumed

they were fairy tales—except Lubicchi. He is still bullied over his father’s

stories, but Lubicchi could potentially face harsher repercussions from Chimney

Town’s inquisition, which does not take kindly to such heresy.

One

magical Halloween, a mysterious, cosmic heart lands in a landfill, where it

assembles and animates a literal “junk man.” Naturally, the fearful and

provincial townspeople shun him, but he finds a friend in Lubicchi, who dubs

him “Poupelle.” Of course, the Inquisition wants to capture the “man of junk,”

but they evade the theocratic enforcers, with the help of Scoop, a

thrill-seeking Libertarian tunnel pirate. Together, they might even prove the existence

of stars.

In

fact, the film, based on a children’s book written by Japanese comedian Akihiro

Nishino, is fairly Libertarian, even though it is based on an economic fallacy.

Supposedly, Chimney Town was created by a cult devoted to an economist, who

invented money that decays for the sake of economic equality. Of course, our

money also gets rotten over time. It is called inflation and lately the rate of

decay has been blisteringly fast—and it has been working families like Lubicchi’s

that are hurt most.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, “Independent Film” was a “thing.” Today,

the Independent Spirit Award nominations are nearly indistinguishable from the

Oscars. Probably a good third of the films at Sundance already have

distribution and nearly all of them have their own publicists. However, back

then there was the quaint idea that indie filmmakers could finally make very

personal statements. In fact, that was maybe the whole point. Kevin Smith’s Clerks

was a big part of the romantic vision of indie filmmaking. His career has

had its ups and downs, but Malcolm Ingram essentially serves up an infomercial

for the Smith’s brand with Clerk, which releases this Tuesday on DVD.

If

you paid any attention to the “golden age” of indie film, you probably remember

how fresh and honest Clerks felt when it first released. Then he

experienced the sophomore jinx with Mall Rats, but as someone who worked

in a 7-11 and then a mall bookstore, both films felt pretty darned on target.

Nevertheless, Smith is relatively forthright addressing the critical drubbing

of his second film and the challenges it posed to his career. Frankly, this is might

be the best part of Ingram’s doc, because the rest largely celebrates his hits

(Chasing Amy) or excuses away his bombs (Jersey Girl, Cop Out).

Clerk

might

technically be Ingram’s film, but it is clearly Smith’s show. It is interesting

to hear a filmmaker talk at length about his work, especially one who is also a

personable performer (in podcasts and one-man shows) like Smith. However, Clerk

would have benefited as a film if Ingram had included dissenting critical

voices to argue he is just an overrated mediocrity, or whatever. To his credit,

Smith addresses the Harvey Weinstein issue head-on (Miramax distributed most of

his early films), but Ingram never challenges him when he claims he never knew

about the film mogul’s predatory behavior (it seems like a lot of people in the

business did).

For a year like 2021, eligibility for “best of lists” is a bit of a tricky

issue, so this top 10 is for any film that had any meaningful theatrical or

premiere consumer distribution, more or less. Thanks again for Covid Xi

Jinping.

1.

Revolution of Our Times: I’ve seen a lot of Hong Kong Umbrella

documentaries, but I was still shocked by the police brutality it documents and

moved by the commitment of the democracy protesters.

2.

Beijing Spring: Informative and surprisingly visually dynamic documentary

on art, freedom, and oppression in early Deng-era China.

3.

Bob Spit: Punk gets super-meta, but stays super-rude. Plus, its Brazilian.

4.

Wife of a Spy: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s first real stab at legit Hitchcockian

noir knocks it out of the park.

5.

There is No Evil: Mohammad Rasoulof quietly but devastatingly indicts

the Iranian [in]justice system.

6.

PIG: Nic Cage gives understatement a try and lo & behold, it works.

7.

Undine: Christian Petzold’s latest is mysterious and haunting in every

sense of the words.

8. To What Remains: A moving tribute to the ultimate sacrifice of veterans

and the continuing sacrifices their families keep making.

9.

Boss Level: Total meathead entertainment, but also constantly inventive.

Fictional Rock Spring School has quite a rigorous academic calendar, considering

its classes remain in schedule through Christmas Eve. Sadly, Prof. Ellis Fowler

last class of the term might be his last day ever, or perhaps not. When it

comes to Christmas episodes of uncanny anthology series, everyone usually

focuses on The Twilight Zone’s “Night of the Meek,” because of the Santa

suit, but for pure seasonal sentiment it is tough to beat “The Changing of the

Guard,” another foray into the Zone written by the great Rod Serling

himself.

Fowler

presents himself like a Prof. Kingsfield, but deep down, he is a real softy.

That is why his students really love him, even though they jokingly refer to

him as “Weird Beard.” Unfortunately, the prep school administration does not

appreciate him as much. Since he has long declined to retire, despite having

well passed the qualifying age, they have decided to make the decision for him.

After all, he insists on teaching dead white male writers like John Donne and

A.E. Housman. Now they can finally bring in a Third World Studies specialist to

replace him (at least that is what would happen if the episode were set in

contemporary times).

Believing

himself a failure, the despondent Fowler returns to campus intending to commit

suicide in his classroom. However, is shocked to find there an assembly of his

former students, who died young in service to their country. What starts as Goodbye

Mr. Chips turns into It’s a Wonderful Life, ironically just when

Fowler takes his detour into The Twilight Zone.

This

episode offers up all kinds of heartstring tugging and moral uplift, but it

also should be conclusively cement Donald Pleasence’s standing as a genre

legend. Years after his death, his forceful performance as Dr. Sam Loomis

continues to loom over and drive the Halloween franchise. He was a Bond

villain and appeared with Peter Cushing in films like the The Devil’s Men and

From Beyond the Grave, yet he is often unfairly overlooked for his significant

Twilight Zone appearance that is much more akin to his classic

supporting performance in The Great Escape.

This BBC-produced miniseries might have been set in the state of Georgia

rather than Scotland. Had the Scottish independence referendum passed, the

Atlantic Fleet’s King’s Bay submarine base was one of the proposed contingency

homes for the United Kingdom’s Vanguard subs (being a NATO port). Apparently, nationalist

politicians are still determined to evict the UK’s nuclear subs and they are

willing to capitalize on a murder committed on-board to do so. Initially, a

civilian DCI finds herself investigating the suspicious death, but she is soon

pulled into a web of sabotage, espionage, and politics in Tom Edge’s Vigil,

which premieres today on Peacock.

The

Royal Navy surely has its equivalents to MPs and the NCIS so the idea DCI Amy

Silva would be dropped from a helicopter into HMS Vigil’s hatch is a bit far-fetched.

In the US Navy, sub crew are thoroughly vetted both physically and emotionally,

to ensure they can withstand the demands of submerged service. Presumably, the

Royal Navy does likewise, so it is unlikely a malcontent like the late Craig

Burke and his thuggish nemesis Gary Walsh would be assigned such duty. Of

course, you could never find submarine passages wide enough for sailors to walk

side-by-side, but hey, dramatic license.

Regardless,

if you can get past the dubiousness of Vigil’s premise, its sub-bound

dramatic dynamics, and the unrealistic representation of its setting, it is

actually a surprisingly suspenseful thriller. As Silva investigates the crime

scene, her colleague (and ex-lover) DS Kirsten Longacre dives into Burke’s

history, including his romantic involvement with a woman active in the Scottish

anti-nuclear movement.

Of

course, much like the “three-hour cruise” of Gilligan’s Island, Silva’s

three-day embedment with Vigil is soon extended, due to grave mechanical

problems and ominous Russian submarine activity. Supposedly, the coxswain,

Warrant Officer Elliot Glover will be facilitating her inquiries, but nobody

wants to talk to her. Inevitably though, the Vigil’s captain, Commander Neil

Newsome starts to begrudgingly respect her, as she uncovers information on the

secret sabotage campaign, mostly likely related to Burke’s murder.

Even

if it does not pass muster with Jane’s Defense Weekly readers, Vigil’s

procedural mystery and submarine techno-thriller elements are totally

grabby and addictively compelling. On the other hand, the flashbacks to Silva’s

backstory, including guilt over the death of her pseudo-fiancé, her relationship

with her presumptive step-daughter, and her aborted romance with Longacre, are whiny,

overwrought, and gratingly distracting from everything that actually works in Vigil.

If we could cut out all that cringy melodrama, it would probably be a much

tighter and tonally consistent five episodes, versus six with the bloated soap

opera interludes.

That

said, Suranne Jones and Rose Leslie are both very good when they get to play

competent, intuitive cops, rather than wounded lovers. Paterson Joseph plays

Commander Newsome with a 100% credible military bearing, but also with an

appropriate edge, given his somewhat tense relationship with his overbearing,

politically connected executive officer Lt. Commander Mark Prentice. Initially,

Prentice is positioned as a cliched martinet, but Adam James nicely fleshes him

out, as he becomes more complicated in later episodes. Shaun Evans also solidly

portrays Glover’s intriguing ambiguity and Stephen Dillane is all business as Admiral

Shaw, the serious-as-a-heart-attack commander of the Valiant fleet.

Crypto has come a long way baby, but it is still valid to ask whether it is truly

money, by the classical economic definition. It can certainly function as a

store of value, although it did not turn out that way for customers of QuadrigaCX.

However, its lofty but fluctuating exchange rate does not make it practical as

a medium of exchange or a measure of value. Prices that go on for eight or nine

decimal places simply are not efficient. Yet, only Paul Krugman would argue

crypto has no value (for the record, I’m suggesting it is too valuable to serve

as currency). As a result, many people were ruined by the mysterious disappearance

of their QuadrigaCX holdings. The murky circumstances surrounding the death of

the exchange’s co-founder and the subsequent exchange lock-out are chronicled

in Sheona McDonald’s Dead Man’s Switch, which premieres tomorrow on

Discovery+.

There

was a time when QuadrigaCX was Canada’s largest exchange. Founders Gerald Cotten

and Michael Patryn came around at the right time and they shrewdly courted the Vancouver

crypto community. Cotten was the Zuckerbergish public face of the company, so

when he had a falling out with Patryn, he became the only one with access to

Quadriga’s off-line “cold wallets.” That meant when he died while visiting

India (for rather uncharacteristic reasons) nobody could access the bulk of the

crypto investments parked in the exchange.

Millions

of dollars-Canadian were lost, spurring fruitless audits and litigation. Not

surprisingly, many of Quadriga’s creditors started to suspect Cotten faked his

death and absconded with their Coins when the founders’ scandalous background

came to light. McDonald does a great job handling this line of inquiry. She

never indulges in fanciful speculation, but what she uncovers in India is

definitely grounds for suspicion. In fact, it is utterly bizarre and undeniably

fishy.

Even a master craftsman like Gustav Stickley could be undone by the fatal

combination of high inflation and high interest rates. For a while, he was a leading

furniture manufacturer, wholesaler, and retailer, as well as a pioneering

design publisher, but he was undone by soaring consumer prices and a credit

crunch. Although largely forgotten by the 1920’s, he would be rediscovered posthumously

in the 1960’s (thereabouts). Director Herb Stratford and his co-writer-co-producer,

Stickley biographer David Cathers chronicle the designer’s life and legacy in Gustav

Stickley, which premieres today on OVID.tv.

After

a downturn in his family’s fortunes, the young Stickley found unexpected satisfaction

working in his uncle’s furniture factory. Before long, he and two brothers had

their own furniture manufacturing company. Most of their output was

conventional and their partnership would not last long. However, “Gus” stayed

in the business, perfecting his own style.

Directly

influenced by John Ruskin and William Morris (the essayist-textile artist, not

the talent agent), Stickley developed furniture that rejected the faux-Euro-Chippendale

ornamentation that was then commonplace in the American market. His pieces

embraced the grain and weightiness of the wood and emphasized the pegs, joints,

and fasteners holding them together. They were rugged, but not crude. With the

arrival of designer-architect Harvey Ellis, Stickley’s furniture line somewhat

moved away from its Spartan austerity, adding decorative wood inlays.

To

untrained eyes, vintage Stickley appears like it would be extremely compatible

with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie period, especially pieces with the Ellis

inlays. Although it was decades before Stickley was reappraised by critics and

collectors, his work also looks like it could have been an early, subconscious

influence for some of the WPA furniture craftsmen. If you appreciate one, there

is a high degree of likelihood you would also appreciate the other.

Whether it came from a lab leak or a wet market, there is no serious debate that

the CCP regime in China covered up the Covid outbreak we are all still enjoying

two years later. However, the folks managing the Resident Evil franchise

apparently did not notice. In their new anime series, it is the American

government that covered-up the zombie viral outbreak in Raccoon City and now

the corrupt Defense Secretary hopes to provoke a war with China to distract the

President. Fan favorite characters Leon Kennedy and Claire Redfield must save

the day in the anime series Resident Evil: Infinite Darkness, directed

by Eiichiro Hasumi, which releases tomorrow on DVD and BluRay.

Something

bad happened in Penamstan six years ago. It started out like Black Hawk Down,

but then the zombies showed up. The leader of the “Mad Dogs” unit barely

survived. Now, he is known as the “Hero of Penamstan,” but he is uncomfortable

with that title. Likewise, Kennedy would be uncomfortable to be called the “Hero

of Raccoon City,” but it gave him enough credibility for the President to ask

for him by name.

He

and the Mad Dog commando will be investigating Sec. Wilson’s suspicions that

China was behind the Penamstan incident, along with Shen May, a Chinese

American officer, who still has highly-connected family in Shanghai. Meanwhile,

Redfield turns up evidence of a suspicious biological agent is still infecting

residents of Penamstan, but there are people in the administration who want to keep

a lid on her allegations.

Since

there have already been six Resident Evil films in the Mila Jovovich

continuity, a reboot, and three anime features, so practically no time is given developing

Kennedy and Redfield. You either know them or you don’t. Jason “the Mad Dog” is

not much more than a stock character either. Although Infinite Darkness is

packaged as a series, there are only four twenty-four-minute episodes, so it is

really more like another anime feature cut into quarters. There is plenty of

action, but it often looks more like a video game on-screen, which sort of

makes sense, given its source material. There is also a fair amount of

halls-of-power intrigue, but it is largely derivative and entirely half-baked.

Outlaws are cool, so there is always a younger generation eager to follow in

their footsteps. The question is whether Millennials are equal to the task. It

is always tough to compare the original generation with those who come after

them, but the disparity is particularly glaring in the case of “Outlaw Country.”

Nearly forty years after the late James Szalapski filmed his classic

documentary, Heartworn Highways, Wayne Price applied his methods to a

new generation of Nashville musicians in Heartworn Highways Revisited,

which has now is available on DVD and BluRay from Kino Lorber.

Sadly,

Towne Van Zandt died from his hardcore outlaw lifestyle in 1997, so he does not

appear as an honored alumnus in Revisited. Guy Clark and Steve Young are

no longer with us either, but Price was able to film them before they passed.

As you might expect, their scenes, along with those of David Allan Coe, are the

best in the self-positioned sequel. However, the absence of the original doc’s

biggest star, Charlie Daniels is quite glaring. Could it be the rightward turn

his politics took after September 11?

In

fact, there seems to be a rather perverse slant to the film, considering the

general market for Country music (including the Outlaw variety), reflected for

instance in Bobby Bare Jr’s joke about Republicans and Robert Ellis’s “Sing

Along,” which describes the horrors of a fire-and-brimstone upbringing.

On

the other hand, it is nice to hear some of the musicians incorporating jazz and

blues influences. The acutely personal Outlaw singer-songwriter tradition is clearly

still represented by the likes of Justin Towne Earle’s “Am I that Lonely

Tonight” and Ellis’s “Tour Song.” However, there is no question the jaw-dropper

highlight of the film is Guy Clark’s climatic performance of “L.A. Freeway,”

with most of the younger musicians offering reverential support.

It is the perfect DVD gift for all the tramps, ramblers, and hobos on your

Christmas list. The artists it documents would probably be okay with that

characterization. They were the performers associated with the early development

of the “Outlaw Country” school of Country & Western music. The movement’s

biggest stars (like Willie Nelson) eventually filed off their rough edges, but

the many of the most talented outlaws achieved cult fandom and status as country

musicians’ country musicians. Those were the sort of artists James Szalapski recorded

in performance throughout his 1976 documentary Heartworn Highways, which

has now been restored and is available on DVD and BluRay from Kino Lorber.

Technically,

there are talking head segments in Heartworn, but they feel more like

chill hang-out sessions. People talk to each other rather than the camera. They

drink too, which contributes to the idiosyncratic vibe. Szalapski also often

marries up the music with impressionist footage of the highways and roadhouses

that make up a traveling country artist’s world.

Frankly,

those who have preconceived notions probably should not think of tunes like Guy

Clark’s “That Old Time Feelin,’” Townes Van Zandt’s “Waiting’ Around to Die,”

David Allan Coe’s “I Still Sing the Old Songs,” and Steve Young’s “Alabama

Highway” as country songs at all. Consider them Americana roots music, because

they tap into deep, archetypal sources. They are profoundly felt and cut to the

bone.

In

some ways, the film confirms a few Country cliches, in that many of these tunes

very definitely address God, booze, patriotism, and prison. Yet, there is also Van

Zandt serenading to tears his friend and neighbor, “Uncle” Seymour Washington, the

so-called “Walking Blacksmith,” who was known for supporting both black and

white musicians. The truth is, all those New York and Beltway writers who

churned out think-pieces wondering “how can we ever understand those Red States”

should listen to tunes like “I Still Sing the Old Songs.”

Szalapski’s

film appreciated in reputation over time, because he had the good fortune to

catch a number of artists on the way up. Even though Van Zandt was a supporting

character in Ethan Hawke’s Blaze, probably the biggest attraction, then

and now, would be the Charlie Daniels Band. Yet, it is instructive to see how

they were still operating outside the supposed mainstream. It looks like their concert

performance takes place in a large school gymnasium, but the place is truly

packed to the rafters.

This adaptation of Jana Egle’s short stories is sort of like a Latvian Short

Cuts. It is also a coming-of-age story—a really dark one. Markuss is a

tough kid to love, but we come to understand just how unloved he feels in Dace

Puce’s The Pit, Latvia’s official Oscar submission for best

international feature, which releases today in theaters and exclusively on Film

Movement Plus.

Markuss

is in big trouble, because he lured Emilija, a snotty little princess in his

new neighborhood, into a pit in the woods and left her there. He was already a

pariah in this provincial town. Now he is considered a monster. His

grandmother, who is reluctantly serving as his guardian, seems to openly resent

his presence. The rest of his local kin treats him with cold disdain, but their

dysfunctional and sometimes abusive behavior behind closed doors is not so very

different. His only friend is Sailor, the town outcast, whom his grandmother

helps to support, despite her obvious contempt.

Some

of the revelations Puce and co-screenwriter Monta Gagane have in store for

viewers are fairly logical (a nicer term than predictable, in this case), but

the way they emerge organically as the film progresses is still quite potent.

There are some flashbacks, but they are employed judiciously and cleanly. After

ten minutes, viewers will despise Markuss, but after seventy minutes, hearts

will ache for him. It is a drastic dramatic reversal, but it is well-earned.

It

is also helps that young Damir Onackis’ lead performance is remarkably

powerful. He is raw and honest—quiet, but violent. This could very well be the

best youthful performance of the year. Dace Eversa surprises us down the stretch

as Grandma Solveiga, while the acutely human sadness of Indra Burkovaska’s

Sailor is the perfect counterpoint to Markuss’s rage and confusion.

If science fiction predicts something enough times, does that mean it will truly

come to pass? Should that be so, the terminally ill will eventually be able to

replace themselves with healthy clones that carry their memories. We have

already seen dying fathers come to terms with their clone successors in Guy

Moshe’s LX 2048 and the “Tom” episode of Solos, so we can

anticipate the mixed emotions Cameron Turner feels in Benjamin Cleary’s Swan

Song, which premieres tomorrow on Apple TV+.

So,

Turner is doing poorly. His outlook is fatal, but he hasn’t told his wife Poppy

or their son anything. It is better that way, if he goes through with the

radical treatment proposed by Dr. Scott. She will clone him in every respect,

except for that obvious congenital defect, including his memories. However, they

will need his help to verify all his old recollections synchronized acutely.

That trip down memory lane will be painful, especially since it requires

spending time with “Jack,” his replacement.

Despite

the basic science fiction premise, Swan Song is more a film about death

and letting go than the speculative implications of cloning. True, there are

self-driving cars, but those are supposed to be coming right around the corner,

finally. Fortunately, much of that drama is quite well done, especially the

strange relationship that develops between Turner and his clone.

Mahershala

Ali is very good in what is sort of, but not exactly a dual role, as Turner and

his clone. Frankly, it is quite impressive how good he is playing opposite

himself. He also has some nice sequences with Naomie Harris, as his wife Poppy,

especially during memories of their first meetings. Harris does indeed have some

effective moments, but her character’s complete lack of intuition somewhat

strains credulity.

If Jo Harding had to lose a year to amnesia, her most recent would be the

one to forget. Her dog died, she finally checked her dementia-plagued father

into a care-home, and she bitterly quarreled with both her son and her best

friend. It is unclear whether it is any consolation, but she also suspects she

was having an affair. With whom, she has no idea. Bits

and pieces will come back to her in Angela Pell’s six-part adaptation of Amanda

Reynolds’ novel, Close to Me, which premieres tomorrow on Sundance Now.

Harding

took a bad step on her staircase and suddenly one year was gone. (Honestly, the

disorienting tile pattern of their foyer could make anyone swoon.) Or was she

pushed? That is what she starts to suspect, even though the doctors warn her

she will be a bit spacy and “disinhibited” for a while. Frankly, it seems like

she was always a little blunt, at least judging from the confused flashbacks. Regardless,

she will be a lot for her husband Rob to handle. He was the one who found her

bleeding at the bottom of the staircase and he has been acting super-squirrely

ever since she came to.

In

terms of tone, Pell’s adaptation is like a more sexually frank Mary Higgins

Clark thriller. It is very much a woman’s story and a domestic setting, but the

relatively small circle of characters rather limits the potential field of

suspects. Rather awkwardly, Jo Harding can really be a pill, both pre- and

post-accident. After five and a half episodes with her, we were almost

expecting a meta revelation, in which we learn it was a group of exasperated

viewers who pushed her down the stairs. It is also unclear whether this was an

intentional strategy to play up her status as an unreliable narrator or some

dubious characterization choices.

Rather remarkably, the staff of Afghan Films already saved their film archive

from the Taliban once. Sadly, they will probably have to do it again, because

Joe Biden got bored with Afghanistan. Hopefully, Taliban enforcers have not

seen this documentary, but wisely the employees of the state film agency was already

racing to digitize their archive, in recognition of the nation’s continuing

instability. Ariel Nasr documents the history of Afghan cinema and the efforts

to save it in the NFB-produced documentary, The Forbidden Reel, which

screens online as part of the Smithsonian’s Left Unfinished: Recent AfghanCinema series.

Not

surprisingly, the series also features What We Left Unfinished, the

story of five incomplete, rediscovered Soviet Era films that offered in window

into Afghan cinematic history. In fact, the director, Mariam Ghani (who also

happened to be the daughter of former President Ashraf Ghani, now in exile in

the UAE, for obvious reasons) appears throughout Reel, as one of Afghan

Film’s chief supporters and consultants.

Not

unexpectedly, the Taliban did indeed come to burn their country’s cinematic

heritage. However, the forewarned Afghan Film employees were able to hide their

true archive, by serving up their storeroom of international films instead. As

of 2019, they were well into their digitization campaign, with Ghani’s

assistance.

Initially,

the Soviet-era was seen as a boon for filmmaking, but as the puppet government

imprisoned and executed more and more Afghans, many of the directors attached

to Afghan Films joined the Mujahideen, serving in the filmmaking unit attached

to Ahmad Shah Massoud’s fighters. The moderate commander was one of the most

effective at battling the Soviets, but he was tragically assassinated by his

more extreme Taliban rivals, which directly led to an existential crisis for Afghan

Films.

When

watching Forbidden Reel, it is clear Afghanistan does not have to be the

way it is. Most Afghans want to work hard, take care of their families, and

maybe take in a movie now and then. Yet, a lack of will on our part turned back

the clock to 2001. Perhaps most chillingly, we understand many of the people interviewed

by Nasr are now in grave danger, if they have not managed to secure safe passage

out of their country. Obviously, they can’t expect much help from us. We still

have Americans we have yet to evacuate, but the Biden administration is loudly

patting itself on the back, because they believe the total number is “fewer than 12.” (We’re midway through December, by the way.)

Punk is not dead and neither is Bob Spit (a.k.a. Bob Cuspe). Brazilian

cartoonist Angeli thought he had killed off his creation in the pages of his

underground comix Chiclete com Banana, but a punker like Spit is hard to

kill. When word reaches him of his creator’s attempt to do him in, Spit sets

off to give him a piece of his mind in Cesar Cabral’s ultra-meta and super-rude

stop-motion animated feature, Bob Spit: We Do Not Like People, which

opens this Wednesday in Los Angeles.

Spit

is your basic hardnosed, unreconstructed punker. (He is also a bit phlegmy, hence

his name.) Ever since Angeli thought he killed off his best-known creations,

Bob Spit and feminist icon Re Bordosa (who maybe isn’t completely dead either),

he has been somewhat blocked creatively. Maybe because everyone keeps talking

about his iconic characters, including his closest colleague, transgender

cartoonist Laerte, who is quite a fan of Bordosa.

Supposedly,

Spit was killed by a horde of mutant Elton Johns, who symbolize the pestilence

of pop music. However, the perennially angry punk seems to handle them just

fine in the cartoon wasteland he stalks through. Inadvertently, he saves the

goonish Kowalski Brothers, who have been piecing together “prophecies” regarding

him from the pages of Chiclete com Banana. When they show Spit the death

Angeli wrote for him, it makes him mad, so he intends to teach the “old cartoonist”

a lesson. Meanwhile, the animated Angeli has weird dreams and visions of

Bordosa and Laerte, who appears to him as a Roma fortune-teller.

Cabral

takes viewers on a bizarre post-modern animated ride that features the real

voices of Angeli and Laerte, appearing as themselves. It is sort of like an

animated cross between The Young Ones and Wes Craven’s New Nightmare,

but the feral Elton John mutants have no precedent. This is a crazy,

self-referentially Borgesian film, but it stays true to the defiantly anarchic

spirit of the original Bob Spit.

What

unfolds is near-total bedlam, but the stop-motion animation is quite

masterfully rendered. The movement and facial designs are reminiscent of Adam

Elliot’s Mary and Max, but thematically, the two films could not be

more dissimilar. Bob Spit has no interest in personal growth or moral uplift,

but he just might have some insights into the nature of art and the creative

process.

It is hard to enjoy “La Nuit des Enfants,” Morocco’s annual children’s night

festival, when you are a child bride married to a creepy sixty-year-old. The

injustice of Bashira’s situation leaves her particularly vulnerable to a demon

named Bougatate. Her flashback starts the story, but she certainly won’t be its

last victim in Telal Selhami’s Achoura, which releases Tuesday on DVD

and VOD.

Achoura

has

been likened to a Moroccan IT, but for a while, the multiple early

flashbacks make it difficult to understand why. Years after Bashira’s fateful “Children’s

Night,” a group of four friends barely survive an encounter with it, but frankly,

Ali’s brother Samir draws a rather unfortunate fate.

That

was twenty years ago. Despite a pledge to never forget what happened, Ali and his

wife Nadia have largely repressed the incident. However, their estranged friend

Stephane still recollects it vividly, as we can see from his morbid paintings

and performance art. However, they must start remembering when Bougatate is

inadvertently unleashed.

Yes,

the kids who barely survived the monster must reunite to defeat it. Despite

structural similarities to King’s novel (and a lot of tall grass), Achoura is

stylishly creepy. Selhami has a great eye for visuals and the folkloric

elements add further layers of archetypal resonance. However, it really takes about

half-hour for him to finally establish how the first six or seven scenes relate

to each other.

Many millennia from now, will human beings still be wearing cloth masks? The

voice from the future never specifies, but apparently, we evolved to have

telescopic eyeballs on the top of our heads. Mankind survived several extinction-level

events, but fate will eventually catch up with us on the plains of Neptune in

the late composer Johann Johannsson’s unlikely but spiritually-faithful adaptation

of Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, which is now screening at the

Metrograph.

We

are hearing a communication from the far, far future. They want something from

us in the past, but it is not to recruit us to fight aliens, as in The

Tomorrow War. Unfortunately, it will be solar events and cosmic gaseous

bodies that spell mankind’s demise, but they are resigned to it at this point.

Their business is more philosophical.

This

is why Stapledon was always considered so unadaptable. His best-known novels

were not about ray-guns and rocket-ships, but rather the rise and fall of

galactic civilizations and species. Although Johannsson and co-writer Jose

Enrique Macain incorporate a mere fraction of his text into Tilda Swinton’s

anesthetizing voice-overs, they faithfully convey the vibe and sweep of his

work.

To

accompany these grand and sometimes dire descriptions of future humanity,

Johannsson films the imposing and often crumbling Brutalist monuments of the

former Yugoslavia. These de-humanized vistas are lensed in starkly glorious black-and-white

by cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grovlen. Some of them even look akin the statuary

of Easter Island and the neo-primitivist masonry designed by Burle-Marx.

There

is a narrative of sorts to Last and First, but no characters per se.

Yet, there is plenty to intrigue the curious mind, like the development of “navigators,”

a “hardy” folk, who prefer to travel space beyond the range of future man’s

hive-mind telepathy. So, there will still be Red-Staters thousands of millions

of years from now.

Heaven--its not just for dogs anymore. All animals go there, but this isn’t exactly

a paradise with 72 virgins. It is more like an afterlife in the tradition of What

Dreams May Come. It can actually be a pretty scary place, but Whizzy the

mouse might have a friend to go through it with, if they can get past their

earthly history as prey and predator in Jan Bubenicek & Denisa Grimmova’s Even

Mice Belong in Heaven, which releases today on VOD.

Whizzy

is a bit of a scaredy-cat, but she tries to over-compensate by bluffing and

showing off. It is not her fault. She still has lingering trauma from her

father’s death. Ironically, he became a hero to the mice, by saving her from a

fox. She feels compelled to repeat his heroics, by picking a fight with

Whitebelly, a shy, stuttering young fox. Unfortunately, when he gives chase,

they both end up flattened by a car.

Right,

this might not be such a good film for kids, since the cute, furry main

characters literally die in the first ten minutes. It really is more of an

adult beast-fable, sort of in the tradition of Watership Down and Plague

Dogs. However, the animation style definitely signals viewers to expect

something cuter and lighter.

Regardless,

the evolution of Whizzy’s post-mortem relationship with Whitebelly is quite

touching. Whizzy can be more than a little annoying and self-centered, but death

tends to be quite a learning experience. Whitebelly also has a dramatic arc in

store for himself, but by accepting each other, they can overcome the hang-ups

that held them back in life. At least that is what Heaven is trying to teach,

if they would only pay attention.

Isaac Lemay has been cursed by a tribal elder, who has apparently read his

Sophocles. The old man actually called it a prophecy, but the way Lemay lets it

consume him definitely makes it a curse. Told he will one day be killed by one

of his offspring, Lemay sets out to systematically kill his kin in Tim Sutton’s

The Last Son, which releases today in theaters and on-demand.

Killing

is what Lemay does best. It is what earned him the “curse.” However, he still

found time to visit many prostitutes. Anna is one of the last, whose sons are

not yet accounted for. Lemay makes quick work of the one she acknowledged, but

Cal, the one she gave up for adoption for his own protection, is a slippery

outlaw. In fact, he is a lot like his old man.

Cal’s

feelings towards his mother are a little confused (again, see the literary allusion

above), but the man who makes her swoon is Solomon, a hardboiled cavalry

officer. Having been raised by the Cheyenne as a foundling, Solomon always

remains a bit of an outsider in white society. Nevertheless, he is determined

to bring to justice the outlaws who stole a gatling gun and murdered a

detachment of troops. Yes, that would be Cal and his associates.

This

is a dramatic change of pace for Sutton, who was previously known for moody

art-house fare like Memphis. There is still a whole lot of brooding in Last

Son, but everyone also takes care of Western genre business. As Westerns

go, it is super-revisionist, but there is also a pinch of Weird West too, which

makes things interesting.

Like a lot of people, Lucy had a Charlie Brown kind of New Year’s last year. This

year, her Christmas is not panning out either. Lucy Van Pelt is not the sort of

person you want to disappoint, so Linus and Charlie Brown agree to help make

her New Year’s Eve party an unforgettable bash. Yet, her bossiness keeps

getting in the way in Snoopy Presents: For Auld Lang Syne (directed by

Clay Kaytis), the first new Peanuts holiday special in ten years, which

premieres tomorrow on Apple TV+.

It

is December, but we end up skipping over Christmas, after Grandma Van Pelt

calls to say she can’t come this year. Linus is a little relieved, but Lucy is

very disappointed. To cheer herself up, she decides to throw herself a New Year’s

party. Naturally, she assigns everyone a job to do, but they wouldn’t mind, if

she would just let them do things their ways.

Meanwhile,

Snoopy’s entire litter is visiting for the holidays, including big lovable Olaf

and his sister Belle. Crusty Spike wants to finally get a picture of them all

together, but his efforts are constantly frustrated.

Evidently,

Apple’s Peanuts originals must all use Snoopy rather than Charlie Brown

in the title. The “Snoopy Presents” makes him sound like a celebrity executive

producer, but this is probably the best of the Apple-produced Peanuts programming

to date. Kaytis and co-writers Alex Galatis and Scott Montgomery rekindle the

spirit of the eternal Peanuts classics, even though they give Lucy some

vulnerability and sentimentality that we have never seen from her before. (Seriously,

she is the girl with the football, remember?)

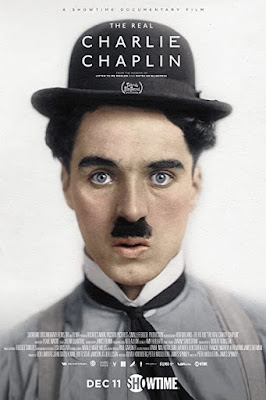

Enjoy this documentary while you can. It seems like it will only be a matter

of time before Charlie Chaplin gets an Ansel Elgort-Woody Allen-style canceling. After all,

he had a habit of marrying young women in their early teens. According to his

second wife’s memoir, Chaplin was quite an abusive husband. He also financially

supported his friend Fatty Arbuckle after the screen comedian was acquitted on

notorious rape and murder charges. Of course, Chaplin’s stature as the first

true mega-movie star and a genuine cinematic auteur should trump all that—but it

doesn’t work that way under the current anti-cultural climate. Probably

arriving just under the wire, Peter Middleton & James Spinney’s The Real

Charlie Chaplin premieres this Saturday on Showtime.

Chaplin’s

origins could be any humbler. After his father absconded and his mother was institutionalized,

the young boy was literally consigned to a work-house. Eventually, he found

success as a vaudeville performer in a particularly physical troupe. While on

tour in America, he was signed to a film contract by Mack Sennett. Chaplin had

a less than auspicious debut, but once he adopted his famous “tramp” persona, his

career sky-rocketed.

By

any measure, Chapin was the biggest, traffic-stopping star of the silent era.

He was such a big star, he could still produce a silent classic like Modern

Times in 1936, well after the industry adopted sound as a standard. He

eventually went talkie with his classic satire The Great Dictator, which

skewered Adolph Hitler mercilessly. However, much of the pro-Soviet sounding rhetoric

he engaged in during this time would come back to haunt him. Yet, arguably,

Chaplin’s antagonism with the HUAC Committee has ironically helped insulate him

from criticism of his personal life.

Indeed,

that was certainly true of prior bio-docs, like partisan spin displayed in Chaplin—Legendof the Century. Instead, The Real Charlie Chaplin does a decent job

of presenting a comprehensive warts-and-all portrait of Chaplin that never

whitewashes his problematic personal behavior. They still largely give him a

pass on his political pronouncements, even though they happened at a time when

the Moscow Show Trials were well in public record (but the Ukrainian Holodomor

genocide story was still getting spiked in Western media outlets). Still, this

is not hagiography, by any measure.

7.4 million Hongkongers have lost their freedom and the younger generations

that protested were beaten, battered, and arrested without just cause by the

Hong Kong police. Yet, it has all been remarkably well documented, for those

who have not chosen to turn a blind-eye. Recent documentaries like Days Before Dawn and We Have Boots have done excellent work recording the

street protests and the violent tactics used to suppress them, but the shocking

brutality exposed in this film surpasses them all. Your heart will ache and

your jaw will drop after watching Kiwi Chow’s Revolution in Our Times,

which opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles.

Chow

previously helmed “Self-Immolator,” an astonishingly bold contribution to the narrative

anthology film Ten Years. That was a biting critique of what was then

the creeping specter of Mainland oppression. In Revolution, he took to

the streets and the safe houses, shooting protesters guerilla-style, as they

manned barricades and fled from raging police detachments. He provides plenty

of context, but essentially picks up with the later “Extradition Bill” demonstrations

rather than going back to the original 2014 Umbrella protests.

Most

of the subjects he follows are young “Valliants,” the more confrontational

protesters, rather than the self-described “Non-Violents” led by Benny Tai.

Although their voices are distorted and their faces are pixelated, for their

own protection, viewers will come to care about them very much, especially as

they increasingly come under literal fire. Some of this footage is especially

raw and shocking, but one of the biggest takeaways from Chow’s doc is the

respect Tai expresses for the Valliants, acknowledging just how much they

risked for freedom.

There

are indeed some remarkable scenes, such as aerial footage of the “Be Water”

styled protesters, seen from above as they retreat and disperse over a dozen or

so city blocks, to keep ahead of advancing police shock troops. However,

viewers should brace themselves for video of the vicious 721 Yuen Long train

station attack, conducted by white-shirted (suspected Triad) gangs with the

obvious collusion of the HK cops. Independent journalist Gwyneth Ho was there

and reported on the carnage as it happened, getting severely beaten for her

troubles. Fortunately, she survived to address on-camera the attack and the

events that led up to it.