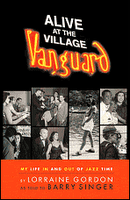

Alive at the Village Vanguard: My Life in and Out of Jazz Time

By Lorraine Gordon as told to Barry Singer

Hal Leonard

0-634-07399-0

I have never met Lorraine Gordon but she always seems nice when I visit her club, the legendary Village Vanguard. I have also heard from musicians that she runs a tight ship. Getting to the gig late is not recommended. Gordon’s life is inextricably intertwined with jazz history, as she describes in her memoir Alive at the Village Vanguard.

Gordon discovered jazz at a young age, and her love of the music led her to meet and ultimately marry Alfred Lion, the German émigré who co-founded legendary Blue Note Records with Francis Wolff. (Alive includes a beautiful Wolff portrait of her.) Blue Note fans will be fascinated to read Gordon’s eye-witness account of Blue Notes early years. Gordon worked side-by-side with Lion to build the independent label, both in the office and the recording studio. Gordon recalls:

“Alfred and I sat in the recording booth behind a glass wall. We’d discuss what numbers they wanted to play, put together ten tunes, each tune three minutes long.” (p. 50)

Having seen the care that went into selecting master takes, Gordon has no use for the proliferation of alternate takes on reissues. Of Lion’s judgment as a producer, she writes:

“He was a true perfectionist about everything, and he was usually right. We would talk about takes after each recording; we’d listen and simply pick the best . . . That’s what I don’t like about what these so-called archivists are doing today: they’re hauling every take out of the vault; they’re first, second takes, third takes, fourth takes and issuing them. Alfred would never have done that.” (p. 78)

One of Blue Note’s most important early signings was Thelonious Monk, who became Gordon’s “personal mission.” In her words” “we sort of became part of the Monk family.” (p. 67) She would even convince Max Gordon, the owner of the Village Vanguard, to book Monk for a week. Unfortunately the Vanguard really lived up to its name that week, as audiences just were not ready for Monk. As Gordon recalls: “Nobody came. None of the so-called jazz critics. None of the so-called cognoscenti. Zilch.” (p. 96)

Monk’s stand may have been disappointing from a business perspective. However, a few years later, Gordon divorced Lion and married Max Gordon. During her marriage to the night club owner, Gordon raised her family, enjoyed nights out at Gordon’s clubs and got politically active. It was Gordon who introduced Barbara Streisand, then performing at Gordon’s uptown Blue Angel club, to left-wing activism. In an early group interview with Mike Wallace Streisand decidedly under-whelmed her political mentor:

“we talked about our peace movement, and then Mike turned to Barbara. ‘You’re involved with this, too?’ He asked. And Barbara replied—I’ll never forget it—‘Oh yeah, we’re like a bunch of lemmings. We all follow each other and jump off the cliff.’” (p. 147)

In 1989 Max Gordon passed away, and the Lorraine Gordon era began at the Vanguard. While the Blue Angel was a casualty of television age, the shrewd move to an exclusively jazz format kept the West-Village club a going concern. Managing a club in this town is no easy task. As Gordon explains one must deal with:

“the board of health, the fire department, the I.R.S.—all the departments that run your business in New York City, whether you like it or not. (p. 206)

Under Lorraine Gordon’s new management, she tightened up the club’s business practices, and showed extraordinary taste in her bookings, as evidenced by the chronology compiled by Brian Rushton which ends the book. It certainly brings back some great memories of shows I have heard there, including: Joe Wilder, Jason Moran, Clark Terry, Lou Donaldson, Bobby Hutcherson, Roy Hargrove, Greg Osby, Wycliffe Gordon, and of course the Carnegie Hall tribute concert.

Alive will certainly be of interest to jazz fans, particularly Blue Note fanatics. Unlike Richard Cook’s book on Blue Note, Gordon really does provide insights into the label’s early years. Jazz has always faced commercial challenges, but it has found independent entrepreneurs who have taken great risks to see that the music is made available to those who love it. Gordon did that at Blue Note with Lion and Wolff. She continues to provide a home for it at 178 Seventh Avenue South, a sacred space for jazz lovers.

Alive is a quick read, told in a witty, conversational style that holds nothing back. I might not agree with Gordon’s politics, but there’s no arguing with her musical taste. Of course I recommend it. Unlike Henry Kissinger, I want to be welcome to return to the Vanguard.