Biden tells us Zelenskyy refused to believe him when he warned the Ukrainian

President of Putin’s full-scale invasion, but that seems unlikely. After all,

the Ukrainian military volunteers interviewed for this documentary back in 2014

and 2015 all predicted it, sooner rather than later. Some of them have very

personal experiences with Russia’s attempts to undermine their nation, as they

explain in Lesya Kalynska & Ruslan Batytskyi’s documentary, A Rising Fury,

which screens as an “At Home” selection of this year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

Pavlo Pavliv and Svitlana Karabut are trying to

maintain a relationship, but the war in the Donbass region makes it difficult.

His activism started while maintaining the protective barricades at Maidan, but

his military training began earlier, when an older man named Igor, call-sign: “Berkut

(Hawk),” took him under his wing and recruited him for his Airsoft team.

Eventually, Pavliv and Karabut deduce Igor is

actually an undercover Russian operative deliberately targeting marginalized

young Ukrainian men, to turn them against their country. It is chilling example

of organized subversion that ought to make all viewers take note, especially

considering how successful Igor was.

In fact, it is probably the most newsworthy element

of the film, because even though Kalynska & Batytskyi’s coverage of Maidan

and Donbass includes some dramatic footage, it is not radically unlike other

Ukrainian documentaries. However, when taken together with its insights into

Russia’s long-game psy-ops, as represented by Igor, it is quite valuable

indeed.

A Chinese inventor’s new AI implant is a lot like socialism and every

other utopian scheme. The pitch might sound appealing, but as soon as you

experience it first-hand, you realize it is a nightmare. Two lovers are manipulated

into taking the nano-operating system that detects lies, but the reality of its

usage is predictably more likely to split them apart rather than bond them

together in Neysan Sobhani’s Guidance, which releases today on VOD.

Ten

years before the start of the film, there was a catastrophic war that left Han

Maio deeply scarred emotionally. Before the war, she was ambiguously involved

with her childhood sweetheart, Su Jie, the heir to a big tech empire. Now, she

is in a relationship with Mai Zi Xuan, whom she suspects has been unfaithful.

He also has reason to suspect her.

Rather

fatefully, she happened to visit Su Jie the very day Luddite terrorists

launched an attack on his company. Consequently, she spent six hours alone with

him in a safe room. Of course, Mai understands that gave them more than enough

time to revisit old times. As a parting gift, Su Jie gave her two pre-release

doses of NIS, for her and Mai, so they can get a jump on the Brave New World

before everyone else. They literally get red-pilled together, during a romantic

getaway that gets much less romantic once the new computer voices in their

heads call them out each time they bend the truth and point out signs of

deception in their partner.

As

a Chinese language film, Guidance is particularly interesting (and

timely), given it presents a cautionary tale of artificial intelligence

over-reach, at a time when AI surveillance software is identifying Uyghurs to

be rounded-up and incarcerated. Arguably, what the CCP is doing now in Xinjiang

and Tibet is even more dystopian than anything portrayed in the film.

Nevertheless,

Sobhani and co-screenwriters Anders R. Fransson and Daniel Wang vividly

illustrate the perils of the utopian temptation and its unintended

consequences. This is largely character and idea-driven sf, but Sobhani still

offers up an intriguing looking future world.

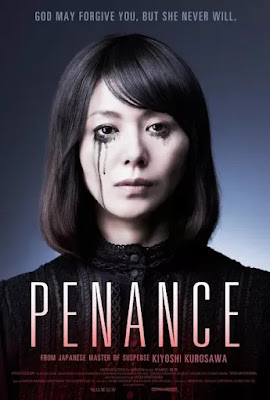

Asako Adachi is a mother worthy of Greek tragedy. When her daughter is murdered,

she offers a grim choice to the girl’s four friends who saw, but could not

identify her killer. Either spend their lives hunting for the murderer, or

eventually accept a karmic retribution that she approves of. That is pretty heavy

for elementary school students, so it is hardly shocking they all turn out to

be emotionally damaged fifteen years later in Japanese auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s

five-episode Penance, which premieres today on OVID.tv.

For

some reason, the killer deliberately chose Emili from her group of friends,

when he approached them on a pretext. They all had a perfect view of him, yet they

all insist they cannot remember his face. Fifteen years later, their bill of

penance starts to come due, but it is not necessarily Adachi who will collect.

Somehow fate, karma, circumstances, and their own bad choices and character

flaws will precipitate crises for all four survivors. Although they each have

very different personalities and perspectives on that fateful day, they all

contact Adachi as they find themselves facing personal disaster.

In

some ways, shy Sae Kikuchi never fully matured, so she married a profoundly

flawed control-freak husband. Maki Shinohara became a strict martinet high

school teacher, who feels compelled to enforce rules without exception. Akiko

Takano is a borderline hikikomori with family issues that are about to get much

worse. Likewise, Yuka Ogawa has an extreme case of sibling rivalry, as well as a

weird cop fetish, born out of that horrific experience.

What

really makes Penance so intriguing is Kyoko Koizumi’s haunting

performance as Adachi. Instead of a ruthless Medea-like vengeful mother, she is

not without sympathy for the four young women. In fact, she even offers them

help, at times. Yet, her eyes are always obsessively on the prize of just

payback. As a result, Koizumi’s work as Adachi is cool and detached, but

weirdly easy to identify with and root for.

Yu

Aoi, Eiko Koike, Sakura Ando and Chizuru Ikewaki all create radically different

personas as the four grown women, but they are all fully developed, with no

shortage of flaws and weaknesses. Together, they demonstrate the perverse and

lingering effects of trauma. Shinohara’s story is possibly the richest, because

it clearly offers extensive commentaries on the compulsive face-saving and CYA-ing

of the Japanese educational system, which in turn is a proxy for society at

large. Takano’s is probably the weakest, because it is pretty easy to predict

where it goes.

Everybody digs the Phantom of the Opera, right? Especially Italian and Chinese genre filmmakers. I dive into the Giallo and Chinese adaptations of and riffs on the Phantom at Nightfire here.

If

you were around in the early 1980s, you might remember how John McEnroe

and Tatum O’Neal were like J-Lo and A-Rod, but with exponentially more

paparazzi interest. Their marriage didn’t last, but he always maintained a

relationship with tennis. The notoriously outspoken athlete is profiled in

Barney Douglas’s documentary McEnroe, which screens during the 2022 Tribeca Film Festival.

Yep,

McEnroe used to argue calls on the court from time to time. He addresses his

famous outbursts quite frankly in the doc. He is not proud of them, but he explains

the issues he was experiencing at the time. He also rarely let them influence

the next point.

Watching

McEnroe reminds us just how long he has been in the public eye. Children

of the 1980s who only vaguely remember the media circus surrounding his

marriage to O’Neal will find Douglas’s coverage eye-opening. Fortunately, he

also handles the tennis stuff well too. Even if you followed his career at the

time, or if you’ve seen Janus Metz’s thoroughly entertaining Borg vs.McEnroe, you will probably get caught up in the drama of McEnroe’s Wimbledon

battles with Bjorn Borg.

In

a bit of a score, McEnroe’s great rival-turned-friend appears on camera to

discuss their comradeship, despite largely retiring from the tennis world and

public life. O’Neal is absent, but the rest of his family discusses McEnroe,

with pretty much the same candor he brings to the film. (We even see his

current wife, Patty Smythe performing on American Bandstand, which is

another blast from the 1980’s past.)

Nobody could match the moves of Fayard and Harold Nicholas. This short documentary

[inadvertently] proves it. Although their prime Hollywood musical numbers were

often cut out to appease the segregationist South, they eventually received

Kennedy Center Honors and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. They appeared

in the clip montage movies That’s Entertainment and That’s Dancing,

but strangely, neither selected their most iconic performance. Contemporary

dancers look back in awe at their leaping steps in Michael Shevloff & Paul

Crowder’s Nicholas Brothers: Stormy Weather, which screens during the

2022 Tribeca Film Festival.

Stormy

Weather was

a star vehicle for Lena Horne, so there would be no call for cutting out the

Nicholas Brothers’ big number. Fittingly, they uncorked one of their greatest

filmed performances, culminating with the brother leaping over each other,

landing into splits, as they worked their way down a grand, Busby Berkeley-ish

staircase. Backed by the Cab Calloway Orchestra, they nailed it in one take,

with no rehearsals.

Dancers

like Savion Glover give unnecessary explanations as to why their performance is

so impressive. Frankly, you can totally get it just from watching them.

However, the short film builds up to the contemporary dancers, Les Twins,

choreographing and performing their own tribute to the Nicholas Brothers’ Stormy

Weather performance—which will absolutely not be a recreation, an important

distinction.

Roy Hargrove was considered one of the “Young Lions” because he was anointed

by Wynton Marsalis, but he was one of the first big jazz headliners to

collaborate with hip hopers, at a time when Marsalis was especially critical of

their aesthetic. Hargrove always stayed true to his own musical conceptions,

like all true jazz artists, but he died too soon, again like far too many jazz

greats. Eliane Henri followed the musician during his final international tour,

documenting what would be his last days in Hargrove, which screens as

part of Tribeca at Home.

Clearly,

we see Hargrove is a bit tired from the road during the opening scene.

Eventually, we also learn his health was also ailing. The musician had been on

dialysis for years. His doctors wanted him to get a kidney transplant, but he

was reluctant, for financial and professional reasons, to take the time off. These

scenes in which Hargrove talks about his health problems are eerily powerful,

like the posthumous anti-smoking PSA Yul Brynner recorded when he was dying of

cancer.

Of

course, Hargrove’s music is also virtuosic, especially the beautiful way he

could caress a ballad. However, none of Hargrove’s originals can be heard

throughout the documentary, because his manager, Larry Clothier (who remains in

charge of his music company), would not approve their release. That leads to

one of the great issues with Henri’s doc.

Henri

makes it very clear she and Clothier often clashed during the making of the

film. The way she put together the film, it certainly looks like Hargrove sided

with her in most matters. Arguably, this reflects the concerns that preoccupied

the musician in his final days, but it ends up injecting her into the film. It

is a more than a minor subplot—it is a major part of the doc.

Is

this really the best way to introduce Hargrove to viewers who might be checking

out Hargrove because of the involvement of his friends Questlove and Erykah

Badu? Admittedly, this is a tricky terrain to navigate, but perhaps removing

all traces of his manager might have been a better option.

After years of futility, Brian has finally invented something that works: an

eco-friendly robot. It runs on cabbages (everyone knows electricity mostly

comes from coal, right?). Somehow, he really cracked the artificial

intelligence, because it largely taught itself to talk by reading the

dictionary. The rest of the maturation process will take more time in Jim

Archer’s Brian and Charles, which opens Friday in New York.

When

we first meet Brian, he is an affable fellow, but he tries too hard to be

chipper, to cover for his loneliness. We see several of his precious DIY

inventions, none of which has any prayer of working. His eccentric-looking robot,

Charles Petrescu, appears to be more of the same, but somehow, after a little

rattling about, he comes alive, like Frosty after the first snow.

Of

course, Brian is delighted to finally have company. However, he tries his best

to keep Petrescu out of sight, because he justifiably fears the Welsh village’s

bullying family of thugs will target his creation. Eventually, the equally shy

Hazel meets Petrescu, who duly impresses her. That in turn builds Brian’s

confidence, to the point he can actually pursue a relationship with her.

However, Petrescu’s restlessness soon leads to rebelliousness.

Initially,

Brian and Charles feels almost toxically cute and quirky, but it

develops some substance and soul during its second half. Petrescu does a lot of

goofy robot-shtick, but Brian’s growth is the arc that really lands. This is a

story of empowerment, as well as the obvious surrogate parenting analog.

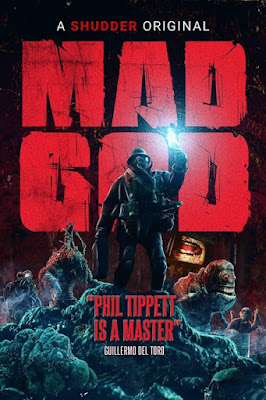

Never stand in the way of a man in a gas mask, who is on a mission. In this

case, the nature of his mission is somewhat open to interpretation, but his

sense of purpose is admirable, as is true of his creator. After thirty years of

intermittent production, special effects wizard (celebrated for his work on Star

Wars, Jurassic Park, and Starship Troopers) Phil Tippett’s truly

long-awaited stop-motion animated feature Mad God premieres tomorrow on

Shudder.

The

“Assassin” travels via a diving bell down to a weird shadowy world that is

beyond dystopian. His assignment is to leave a briefcase bomb within this enemy

netherworld—and then just wait to die. Plenty have failed before him and he

will probably fail too, judging from the pile of briefcases. Unfortunately, an

ugly fate awaits the Assassin, if and when he is captured by the “Surgeon”

(a.k.a. the “Torturer”).

Visually,

Mad God is an amazing film. The design of the Assassin sort of recalls some

of the militaristic animated sequences in The Wall, yet Tippett’s

attention to hair and fiber is also somewhat akin to the style of This Magnificent Cake. Nevertheless, storytelling remains an aspect of filmmaking—and in

this respect Mad God is a little weak. Things like causal effects, motivations,

characterization, and inter-character relationships are only vaguely implied at

best. Clearly, Mad God is intended first-and-foremost to be a spectacle,

which indeed it is.

The

whole point of Mad God is to tour Tippett’s macabre world, much like

Piotr Kamler’s largely narrative-free Chronopolis. Indeed, it truly

looks amazing. Tippett also instills a sense of forward moment thet brings to

mind Frank Vestiel’s underappreciated Eden Log, which also shared a

similarly Boschian aesthetic.

Hotel Portofino looks lovely, but it is hindered by shallow characterization. Exclusive Epoch Times review up here.

Even though it scattered New Orleans musicians, Katrina never the silenced

the music. Jazz Fest continued on-schedule and the Frenchmen and Bourbon Street

clubs were undamaged and reopened for business. However, Covid closed

everything and canceled all the gigs, including Jazz Fest. At least documentary

filmmakers appreciated what we were missing, because there has been a recent boomlet

of NOLA music docs released in theaters or screening at festivals. This one is

a welcomed addition. Ben Chace profiles four stylistically different—but not

too disparate—veteran New Orleans musicians in Music Pictures: New Orleans,

which screens during this year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

Part

one focuses on Irma Thomas, “The Soul Queen,” a highly fitting and logical

place to start. Unlike Martin Shore’s Take Me to the River New Orleans, which

felt compelled to team Thomas up with a younger artist, Ledisi, Chace finds her

sufficiently interesting on her own, because she is. However, he also gives a

bit of time to her sidemen, particularly drummer Johnny Vidacovich, whom Thomas

is happy to share the spotlight with. Hearing them put together a smoldering and

swinging “My Love Is” is a treat.

Likewise, hearing Thomas casually land an a cappella “Our Day Will Come” and

then carefully caress it while recording a lush studio arrangement will give

you good chills. Honestly, watching Music Pictures will make NOLA music

fans realize she is even cooler than they understood.

Benny

Jones Sr. is now the leader of the Treme Brass Band (who were regularly seen in

HBO’s Treme), but he was also a founder of The Dirty Dozen Brass Band,

who really deserve a documentary of their own, for re-popularizing a funkifying

the NOLA brass band tradition. NOLA brass bands have an infectious rhythmic

drive and as a bass and snare drummer, Jones is one of the best putting the

beat on the street. Of course, the entire band makes their groove swing, but

vocalist/alto-player John “Prince” Gilbert gets the time to tell some of the

band’s reminiscences, like when they opened for the Grateful Dead, in Oakland,

on New Year’s Eve.

Little

Freddie King probably lived the blues as much as anyone, if not more so. Yet,

he survived to find fame in Europe and play regular gigs in New Orleans. He probably

has the film’s most colorful anecdotes, but the important thing is he can still

play—and he is a heck of a snappy dresser. It is definitely King’s segment, but

his drummer-manager “Wacko” Wade Wright gets credit for handling all the

business, as well as a lot of King’s personal, medical logistics.

Appropriately,

Music Pictures concludes with New Orleans’ first family of modern jazz,

the Marsalises, whom Shore dubiously ignored. It was a wise choice, considering

Ellis Marsalis, the NOLA jazz patriarch, passed away due to Covid complications

in 2020. Chace focuses on Marsalis’s first and only album length collaboration

with his son Jason (brother of Wynton and Branford) on vibes (whereas on their

previous recordings together, Jason had played drums).

You Know how Tolstoy wrote unhappy families are always unhappy in their own

unique ways? Well, the Jacobs’ dysfunction is in a league of its own—of

fantastical dimensions. The Jacobs all develop a “gift” that always manifests

itself in a different way. Those powers can be dangerous, but the family would

also be in great peril if they were ever discovered, as they very well might be

in Patrick Lowell, Estelle Bouchard, and Charles-Olivier Michaud’s ten-part

French-Canadian series Premonitions, which premieres tomorrow on MHz.

Clara

Jacob is the matriarch of the Jacob family, but she is definitely a cool

grandmother. She even wears a snappy fedora to prove it. Her power is the

ability to see into the future of anyone she is not related to by blood. That

comes in handy for her chosen line of work: professional gambler. She tends to

know when hold them and when to fold them.

She

has few qualms about wielding her powers, but her son Arnaud considers his “gift”

an intrusive violation. He can read people’s minds and even get in there to

erase memories. Having sworn off using them, he has been plagued by severe

migraines. His sister Lilli on the other hand, constantly employs her powers to

bewitch potential lovers. That seems like a bad idea, but viewers will halfway

sympathize when they see the burn scars on her back.

As

a teen, Lilli was thrown into a bonfire by a shadowy member of a witch-hunting

cult dedicated to killing so-called “aberrations” like the Jacobs.

Unfortunately, one of the last survviors of the brethren will try to use her

latest “lover” to get to the Jacobs. Arnaud tried to wipe Pascal Derapse’s

memories of Lilli, but being out of practice, he might have erased too much and

maybe even left a mental connection to himself behind.

Premonitions

is

an unusual and addictive take on the themes of superhero franchises like The

X-Men and Heroes. Although we root for the Jacobs, the plain truth is

Derapse is a victim of the family several times over. First Lilli’s enchantment

drives him into a state of psychotic jealousy and then Arnaud really does a

number on his head. Yet, when the vicious brotherhood enters the picture, Premonitions

even takes on some elements of the horror genre (much more so than Firestarter).

Regardless,

Pascale Bussieres is a terrific lead as the steely Clara. She also has some

keenly compelling and deeply conflicted chemistry with her ex, Jules Samson,

who remains a close friend of Arnaud’s. Nicely played by Benoit Gouin, Samson provides

sympathetic human perspective on the chaos that unfolds.

Marc

Messier is creepy as heck as William Putnam, the aberration-hunter, while Eric

Bruneau is spectacularly unhinged as the brain-scrambled Derapse. Likewise,

Mikhail Ahooja is impressively squirrely playing Arnaud, especially when under

the influence of Derapse.

We need to get horror film directors some sort of group subscription to

Discovery+, because they need to start developing healthier relationships with

food. You would think there would be plenty of healthy eating in this film, because

Simi’s Aunt Claudia is a nutritionist, but the ominous countdown to Easter dinner

clearly implies something awful will be happening in screenwriter-director Peter

Hengl’s Family Dinner, which screens during this year’s Tribeca Film Festival.

Tired

of getting bullied over her weight, Simi invited herself to Aunt Claudia’s rural

Austrian farm over Easter break, in hopes she could get some personal

weight-loss mentoring. The thing is, Claudia (an aunt by a marriage-now-divorced)

is not as welcoming as Simi hoped—but her new husband Stefan is weirdly

hospitable. Her cousin Filipp is probably downright hostile, but he isn’t

getting along so well with his mother and Stefan either.

Despite

some initial misgivings, Aunt Claudia agrees to help Simi, but her rigorous

program borders on the draconian. It seems physically unhealthy and the mind

games grow increasingly sinister. On the other hand, Stefan finds Simi more

useful than Filipp during a hunting trip, so she has that positive

reinforcement going for her.

There

is a lot of slow-boiling in Family Dinner, but it is pretty clear what

is it all heading towards. Not to be spoilery, but if you really think about the

title, it is a dead giveaway. Unfortunately, Hengl expects the climax will be

so shocking, it will make up for the slowness of the build and the lack of

significant plot points.

Early 1991 was an opportune time to be a film student in the Baltics, because

history was exploding daily. It was also a dangerous time for the same reason.

Jazis generally supports Latvian independence from their Soviet occupiers, but

he has yet to mature to the point he can fully appreciate the gravity of the

moment in Viesturs Kairiss’s January, which screens during this year’s

Tribeca Film Festival.

Jazis

wants to be the next Tarkovsky, which would ordinarily alarm most parents, but

his anti-Communist mother is fine with it, along as he gets a draft deferral

from his film school. The last thing she wants is to have her son in the Soviet

army, potentially in harm’s way, while putting down democratic opposition

movements. His father also basically agrees, even though he is a Party member. Unfortunately,

Jazis’s drive and talent level will complicate matters.

For

a while, his affair with Anna, a pretty fellow film student awakens some

passion in him. However, when she falls under the influence of a famous

filmmaker, Jazis spirals into depression and apathy. Yet, maybe the Soviet

military’s attempts to stifle Baltic activism for independence might awaken him

from his lethargy.

Kairiss

skillfully uses a textured lo-fi style (including Super8), integrated with genuine

historical archival footage, to recreate the tenor of the early 1990s in the

Baltics quite vividly and evocatively. You really get a sense of the tension

and potential violence that was literally hinging in the air. In one telling

moments, Jazis asks an elderly woman if she was scared to deliver the food she

baked for demonstrators. “No, I’ve been waiting 50 years for this,” she tells

him.

January

is

highly effective time capsule and mood piece, but Jazis is so moody and sulky,

we hardly get a sense of any character there within him. Arguably, many of the

minor figures, like Jazis’s parents, resonate more than he and his film school-mates.

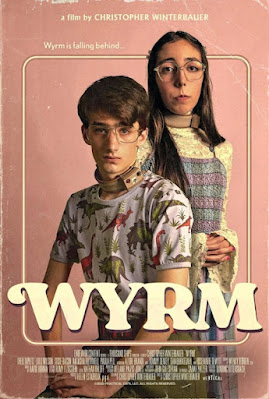

In our world, there is already plenty of pressure on geeky middle school

kids trying to ask someone out. In this alternate 1990s, Wyrm Whitner could be

held back if he doesn’t get to first base fast. His electronic monitoring

collar will know whether he lands that first kiss or not. Of course, his weird

family drama is hardly helpful in screenwriter-director Christopher Winterbauer’s

eccentric coming-of-age fantasy, Wyrm, which releases today on VOD and in

theaters.

Whitner’s

brother Dylan was the jock-hero of his high school, but he wasn’t such a great

brother, or even much of a person. Nevertheless, Wyrm doggedly records audio

tributes for Dylan’s one-year memorial, perhaps as an excuse for the embarrassing

collar obviously still affixed around his neck. Unfortunately, his older sister

Myrcella is not helping, even though she hangs out with Izzy, the new girl

across the street. Instead, she is more interested in earning “credit” with the

Norwegian exchange student and writing poison pen letters to their classmates.

Poor

Wyrm is pretty much on his own, because neither of his parents are much of a

presence in their lives anymore. Instead, their slacker Uncle Chet and his

immigrant girlfriend Flor handle most of the parental duties. Maybe they aren’t

perfect, but at least they are trying.

Wyrm

works

surprisingly well because Winterbauer maintains the logic of the “No Child Left

Alone” system, while not boring us with the deep dive details. Admittedly, the

obsession with preteens’ sexual development feels a little creepy, but the Last-American-Virgin-style

drama is weirdly compelling. Perhaps inadvertently, it also maybe argues how

mandates can be counter-productive. (It is also worth noting the actual “No

Child Left Behind” program was not designed to put pressure on kids. It was

intended to measure the effectiveness of their teachers, who started stressing

their kids out to perform well, just to cover their butts, so riffing on its

name in this context really isn’t fair.)

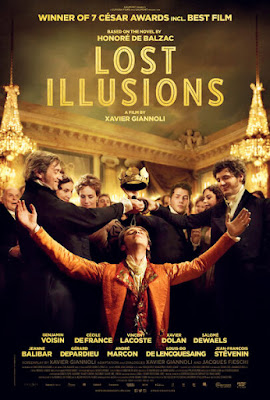

At this point, we really shouldn’t accept newspaper reports as reliable

primary sources. The Washington Post’s embarrassing controversies

regarding stealth edits and misleading corrections are nothing new. Their

imploding newsroom could totally relate to the poisoned-pen scribes at Le

Corsaire-Satan. They traffic in gossip and sell their reviewers’ critical

judgement to the highest bidder. The editor, Etienne Lousteau definitely shapes

its stories to fit his preconceived “narratives,” until someone pays him to

slant them differently. That is just fine with Lucien de Rubempre, until he

finally believes he can attain the noble stature he believes is his birthright in

Xavier Giannoli’s Balzac’s adaptation, Lost Illusions, which opens

tomorrow in New York.

When

people want to annoy de Rumpre, they call him Chardon, because that is

technically his name and the name of his absent father, who ruined his

blue-blooded mother. Like it or not, he is a commoner, so he should not be seen

in compromising situations with Louise de Bargeton, the artistic patron for his

poetry. Nevertheless, she brings him to Paris, risking a scandal that her older

admirer, the Baron du Chatelet manages to suppress, at de Rumpre’s expense.

He

was supposed to slink home to the provinces in disgrace. Instead, de Rumpre

starts writing for Lousteau’s rabble-rousing anti-monarchist newspaper, quickly

adapting to its advertorial ways. Yet, the corrupted poet cannot resist the

temptation of vague promises to restore his family’s lost title.

While much of what transpires is tragic, the caustic characters and their unrestrained

cynicism makes the film play more like a razor-sharp satire. Obviously, the

portrayal of the media as deliberate misinformation peddlers could not be timelier.

Given it was culled from Balzac’s The Human Comedy novel-cycle, Lost

Illusions also clearly establishes the long-standing tradition mercenary

journalistic ethics.

Tony Hillerman was a decorated WWII vet who largely popularized Southwest westerns. Nice to see a well-produced new take on his hardnosed Lt. Joe Leaphorn. EPOCH TIMES review of DARK WINDS now up here.

Apparently, this small island community has brought New England-style weirdness to a

Florida key. It would seem even cults built around Lovecraftian horror find the

Florida economy more inviting. Marie Aldrich’s movie star mother made it clear

she never wanted to return, not even to be buried. That is why the daughter was

so shocked when her mother’s will stipulated she be laid to rest in the island’s

cemetery. It also makes her especially annoyed when she is summoned to the

tourist trap island, by the news her mother’s grave was desecrated. Of course,

someone or something wants to lure her there in Mickey Keating’s Offseason,

which premieres Friday on Shudder.

When

Aldrich arrives with George Darrow, her close-to-being ex, the groundskeeper is

nowhere to be found. The locals are not exactly friendly either. Darrow is

understandably eager to leave the island before the drawbridge closes (or

rather opens) for the duration of the offseason. However, a strange force keeps

steering them into dead-ends.

Keating

is very definitely an up-and-down filmmaker, but Offseason might his

most successful film yet, in terms of crafting mood and atmosphere, even more

so than Psychopaths and Darling. It is also probably his most

polished film, so far.

There

is definitely a lot of Shadow Over Innsmouth vibes going on. The

flashbacks are mostly padding, but the film definitely mines the tight little

island setting for maximum impact. Production designer Sabrena Allen-Biron

notably contributes some memorably eerie analog sets and trappings that really

give the film a distinctive look and texture.

The doughy, pasty-white ninjas of Indiana are about to wage an all-out war.

Who will lose? Eventually everyone, but good taste and dignity will be the

first casualties. Rex isn’t much of a ninja, but he will have to cowboy up if

he wants to save the girl and stop the evil puppy-eating cannibal ninja cult in

writer-director-everything-else Ryan Harrison’s Ninja Badass, which

opens Friday in Los Angeles.

Rex

is a screw-up, who is completely oblivious to his ineptitude. Nevertheless,

when Big Twitty, the leader of the local chapter of the Ninja VIP Super Club,

kidnaps the attractive woman from the pet store (along with their stock of

puppies), Rex decides to “rescue” her back. Fortunately, Haskell, a relatively

law-abiding ninja, agrees to tutor him, for revenge, after Big Twitty tears his

arm off.

Of

course, neither Rex or Haskell can walk and chew gum at the same time. However,

Big Twitty’s estranged daughter Jojo is a match for her father. She has no

illusions regarding Rex’s idiocy and incompetence, but she still reluctantly

teams up with him.

Basically,

Ninja Badass was made for people who find Troma movies too sophisticated

and pretentious. It is chocked full of crude gore and deliberately cheesy

superimposed special effects—including puppies going into the blender.

Seriously, it makes The Greasy Strangler look like a drily witty Noel

Coward comedy.

There

is little point in submitting Ninja Badass to an in-depth critical

analysis. It is meant to be ridiculous and shocking, which it is. However, a

film like this running over one hundred minutes is just excessive. Honestly,

after one hour, we totally get the joke and then some.

This Korean cop thriller is based on a Japanese novel and tries for some serious old

school Infernal Affairs-style Hong Kong vibes. For third-generation

cop, Choi Min-jae, the line between right and wrong is straight as an arrow and

clearly demarcated. For his new boss, Park Kang-joon, that line is wavy and

fuzzy, but fortunately he always has an innate sense of where it is. Choi is

not so sure, which makes his new assignment rather tricky in Lee Kyoo-man’s The

Policeman’s Lineage, which releases today digitally.

Choi

just blew a prosecution on the stand, because he would not lie or dissemble

regarding the rough treatment of the accused. He would not appear to be a good

candidate for Kang’s team on paper, but Internal Affairs transfers him, to serve

as their undercover source anyway. They know Kang will take Choi, because he

has a connection to the naïve cop’s father.

It

turns out the death of Choi’s father remains surrounded in rumors and innuendos.

Both Kang and AI will try to play him, by promising to reveal all. However, as Choi

fils pursues his investigation of Kang, he finds plenty of controversy and

departmental politics, but not the smoking guns he expected.

Lineage

does

not quite rank with the best of Korean thrillers, but for the most part, it is respectably

hardboiled and entertainingly cynical. Bae Young-ik’s adaptation of Joh Sasaki’s

novel tries a little too hard to over-complicate the narrative and all the

behind-the-scenes secret cabal maneuvering sometimes feels a little too pat and

forced.

What happens when the human world encounters that of mystical Diwata folk

spirits? Human authorities naturally try to regulate them and their magic out

of existence. Yet, for one mortal, Diwata magic might hold the only hope for

treating his mysterious ailment in After Lambana, written by Eliza

Victoria and illustrated by Mervin Malonzo, which goes on-sale today.

Conrad

Mendoza de Luna does not know it yet, but there is a significant connection

between him and Ignacio. He just knows him as a grateful IT client, who might

have sources who might provide underground medication for the so-called “Rose”

disease, wherein physical flowers start laying roots, until they bloom through

the skin. It is not always fatal, but de Luna’s is located right over his

heart.

Magic

diseases seem to demand magic cures, but any form of spellcasting is now

illegal now that the gateway to the Diwata realm of Lambana has been forcibly

closed. Those who were in the mortal world at the time must now live in

permanent exile. De Luna will meet several, while following Ignacio through the

back alleys and midnight markets of Metro Manila.

After

Lambana starts

in a noir vibe, but it slowly unfolds into folk-inspired fantasy. Victoria’s

intriguing world-building never feels like mere exposition, because it is so

richly archetypal, and yet grounded in the various traditions found throughout

the Philippines. She convincingly depicts the culture clash between the

materialist mortal world and the magical Diwata realm. It is exactly the sort

of vision of an intersection of the human and the fantastical that the film Bright

should have realized better (but didn’t).

Rondo Hatton honorably served his country in WWI, but his name became

synonymous with villains and monsters. Due to his acromegaly, his was often

cast as hulking brutes, including “The Creeper,” in a few late classic

Universal Monster movies. The pathos of Hatton’s life fascinated several young

fannish future filmmakers, including Robert A. Burns, who is best known as the

art director of the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre and The Hills

Have Eyes. Joe O’Connell tells both their stories in the dramatic-hybrid

documentary Rondo and Bob, which releases tomorrow on VOD.

Although

Hatton’s acromegaly started manifesting after he was admitted to a field

hospital, it was unrelated to the mustard gas attack he had been caught in. Eventually,

his first wife left him, but he went back to his work as a Tampa reporter. He

met his second wife while on assignment at a local society function. She would

have been the obvious choice to be a movie star, but the studio saw Hatton as a

possible replacement for Boris Karloff.

In

addition to being one of the foremost authorities on Hatton, Burns was also the

guy who put all the creepy stuff in Chainsaw Massacre, like the bone

furniture and the chicken in the birdcage. Unlike Hatton, he was apparently somewhat

standoffish around people. One family member diagnosed on the spectrum

speculates Burns might have been too. Regardless, O’Connell’s subjects contrast

greatly, with one looking menacing, but being a wonderful person inside, while

the other looked like anyone else, but was hard to get to know.

As

a result, the Hatton segments are dramatically more compelling. Yet, probably

more time is devoted to Burns, because there is more available material (including

his unreleased proto-found footage microbudget horror film, Scream Test).

Unfortunately, that makes the film feel somewhat unbalanced. We want to spend

more time with Hatton and his second wife, Mabel Housh, because O’Connell and

his cast humanize them so compellingly.

You would think film and television writers would often "rip-from-the-headlines" reference some of

the biggest stories of late 1980s and early 1990s, like say the First Gulf War,

the Fall of the Berlin Wall, and the dissolution of the Soviet Bloc. Yet, you

will find precious few dramas addressing the Tiananmen Square Massacre, despite

audiences’ familiarity of the iconic images of Tank Man and the Goddess of

Democracy statue. It is slim pickings, but the Canadian X-Files knock-off

PSI Factor joined MacGyver and Touched by an Angel, by

producing the Tiananmen-themed episode “Old Wounds” (S3E13), which currently

streams on multiple sites.

Honestly,

this show wasn’t very good, but the premise of “Old Wounds” is somewhat

interesting. Matt Prager’s paranormal investigative team has been summoned to look

into an incident at a tech firm with shady government connections. Adia Carling

was testing an immersive VR game when she suffered real world injuries during

the in-game battle. Weirder still, wounds spontaneously healed.

The

team quickly sleuths out Carling is not from Hong Kong. She is, in fact, an illegal

alien living under an assumed name, who was imprisoned and tortured in China

for her role in the Democracy protests. Somehow, the VR game reopened the old wounds

she suffered while in custody, including the horrific burning of her

left arm. She has the psychic powers to physically heal them, but the team’s

good Dr. Anton Hendricks must hypnotize her, to help her heal her emotional

wounds.

Ideally,

one would prefer to see a serious subject like the Tiananmen Square Massacre

addressed in a more reflective, less exploitative manner, but there are not a lot

of examples out there. Anyone who knows of a Tiananmen Square-themed TV episode,

beyond this MacGyver, or Angel, please shoot me an email. Writers

Jim Purdy & Paula J. Smith treatment of the Massacre and the subsequent

brutal crackdown are not exactly inspired, but director Luc Chalifour manages

to convey the cruelty of CCP torture techniques, while adhering to commercial

broadcast standards.

As a result of the CCP’s draconian “National Security” Law, Hong Kong

residents can no longer safely watch this Frontline documentary,

commemorate the events it chronicles, or search on-line for the image it focuses

on. We must remember for them. In fact, the image of the lone man standing in

front of a column of tanks has become an iconic image of courageous defiance in

the face of overwhelming state oppression. Writer-producer-director Antony

Thomas investigates who he was and how the crackdown on the 1989 democracy protests

drove him to do what he did in Frontline: The Tank Man, which is

available on-line.

Unlike

other vital Tiananmen Massacre documentaries (like Tiananmen: The People vs.The Party and Moving the Mountain), Tank Man largely focuses

on events outside the Square, but that rather makes sense, considering the Tank

Man was blocking tanks on the Boulevard leading out of the Square. In fact, one

of the eye-opening aspects of Thomas’s report is the carnage that resulted when

the PLA strafed apartment buildings around Muxidi Bridge with combat-grade ammunition.

Consequently,

Thomas’s talking heads suggest the majority of killings happened at barricades

set up by average working-class citizens to protect the students in the Square.

Yet, the most senseless murders were those of groups of parents mowed down by

the PLA, who had come to the Square desperate to find their children.

Thomas

and company fully explain the circumstances surrounding the historic film of

Tank Man and how determined the state security apparatus was to prevent it

airing in the international media. They also establish how thoroughly blocked

all images of the protests are on the Chinese internet—as well as the

culpability of Western tech firms like Microsoft, Cisco, and Yahoo in aiding

and abetting the CCP’s censorship.

Thomas

also spends a good deal of time examining the vast economic disparities between

the urban super-rich and the rural underclass. They make valid points regarding

the inequality of China’s economic growth, which has been used to justify the

Party’s ironclad grip on power post-Massacre, but it sort of distracts from sheer

courage and abject horror of the events of 1989.

Do not call Kazem by his name. He prefers the honorific “Atabai” (sort of

like “esquire,” but with more clout) bestowed upon him by his provincial Northwestern

ethnic Azerbaijani hometown. The village holds a lot of painful history for him,

especially the arranged marriage of Kazem’s younger sister, which ended badly—for

her and everyone related to her. Years have passed, but the entire family still

carries guilt from her suicide, but nobody more so than their Atabai. After an

extended absence he returns to reluctantly face his tragic past in Niki Karimi’s

Atabai, opening today in New York.

Kazem

has mixed feelings about being home, but he is happy to see his nephew Aydin.

He has real affection for the dopey teen, but we soon figure out the

well-respected Atabai is also controlling his life, as a way to get back at his

sister’s husband. Frankly, Kazem’s relationship with his own aging father is

nearly as fraught with complications and baggage.

The

returning prodigal once loved and lost during his college years—and still

carries the emotional scars. The last thing he wants from his homecoming would

be a wife, despite some rather mercenary interest. Yet, a woman with her own

tragic reasons to avoid intimacy stirs some long dormant feelings in him.

Atabai

is

a messy but heartfelt film about the long-term effects of grief and trauma. It

is easy to identify with Kazem’s family, even though the particulars of their

circumstances are very much Iranian—starting with the arranged marriage of his

sister, at the distressingly youthful age of fifteen. Arguably, Kazem also gets

away with physically lashing out in rage more than he would in Western

countries. Being an Atabai has its advantages, but everyone understands where

that anger and pain is coming from.

Faster-than-light travel doesn’t change people. It just alters the way they experience of time.

That makes it quite tragic for those who don’t want to go, like the poor

shipman involuntarily pressed into service in L. Ron Hubbard’s To the Stars (from

when he was still readable and not yet messianic). Hundreds of years will pass on

that poor soul’s home before he can return, but for Jack Lambert, only twenty

years have passed on Earth since his teenaged girlfriend left for the space

colonies. Now, she is back and she hasn’t aged a day in Erwann Marshall’s The

Time Capsule, which releases tomorrow on-demand.

Lambert

just suffered through the embarrassing implosion of his senate campaign, so he

and his wife Maggie have come to his dad’s old lake house to regroup. They also

need to sell the place, to help pay down his campaign debts. His old pal

Patrice will help with the handywork. The place holds a lot of memories for

Lambert, so he assumes he is seeing things when he spies his old flame Elise,

who doesn’t look a day older than he remembers her.

It

turns out, after ten years of suspended animation space flight, the colony was still

behind schedule, so they immediately sent Elise and her father back to Earth,

on another 10-year flight. Elise remembers seeing teenaged Lambert in what only

feels like a few weeks prior, but now he is a very married, disappointing politician.

Of course, he never got over her. In fact, it was his controlling father who

arranged for their place in the colony. The adult version of Lambert knows he

cannot just pick-up with Elise (even though the film repeatedly tells us she is

eighteen, so nobody freaks out)—but there is still that old chemistry between

them.

Marshall

and co-screenwriter Chad Fifer cleverly use Relativity as their Macguffin and

skillfully skirt the potential pitfalls (there are no inappropriate moments to

gross-out the overly sensitive). It is actually a really smart way build a

character-driven story atop a science fiction premise. They also shrewdly keep Lambert’s

platform sufficiently vague, so as not to needless alienate viewers.

Today, you can find the name “Genghis Khan” everywhere throughout modern

Mongolia. He sits magnificently astride the monumental equestrian statue

erected in 2008, which has quickly become one of the nation’s top-drawing (and

literally biggest) tourist attractions. Yet, during its years as satellite-state

of the Soviet Union, Genghis Khan was demonized in propaganda and banished from

public discourse. A lot of good change came quickly to Mongolia, but the nation

is still struggling to process subsequent social upheavals. Director-cinematographer-co-producer

Robert H. Lieberman chronicles Mongolia’s glorious history and examines its future

challenges in Echoes of Empire: Beyond Genghis Khan, which opens in

select theaters this Friday.

Ironically,

everything bad you might think about Genghis Khan (a.k.a. Temujin) is largely

the result of Communist disinformation. Yes, he was a conqueror of kingdoms,

whose empire spanned three times the territory Alexander the Great controlled

at his peak. However, as he incorporated new people into his empire, he extended

to them rights they never had. Arguably, Genghis Khan “invented” the right of

religious liberty, as we know it today. He also forbade the kidnapping of women

and established an early form of diplomatic immunity.

Yet, the Communist regime jealousy suppressed celebration of the Mongolian

national hero. (For comparable hypotheticals of a nation erasing its cultural-historical

legacy, imagine the United Kingdom trying to cancel King Arthur, or America

forbidding mention of George Washington, neither of which quite captures the

scope of the Communist Party’s negation of Genghis Khan.)

One

historical episode explained in the film that has particular resonance for our

world today came relatively early in Genghis Khan’s career of conquest, when

the Uyghur people sent an emissary, inviting his invasion of their lands, in

order to liberate them from their oppressors. It came as a surprise to the Mongol

leader, but he obliged.

The

film also archly observes how many commissars from the early Communist era met

suspiciously premature demises—and openly invites the audience to make the

obvious conclusions. Even more fundamentally, when watching Lieberman’s film, viewers

will be immediately struck but the sensitive geographic position Mongolia

occupies, as a functioning democracy nestled between China and Russia.

It

is pretty clear Mongolia is a country Americans should be thinking about much

more than we are. Although Mongolians have pretty forcefully repudiated the

Twentieth Century Communist era (the 130-foot Genghis Khan memorial says so,

loud and clear), they still have to maintain cordial relations with Russia.

They also have considerable cultural ties, having adopted Russian tastes in

opera and ballet, to a surprising extent, as Lieberman and company vividly

illustrate.

Furthermore,

Americans can well relate to Mongolia’s current struggles with increased

urbanization and a widening gap between the city life of Ulaanbaatar (UB) and

the traditional way of life on the steppe. Lieberman takes viewers into the

gers (or yurts) of traditional herders, which look warm and cozy on the steppe.

However, he also illustrates the downsides to coal-heated ger-living in the urban

tent-cities of nomads who have been recently force to relocate to UB.

Yes, all parents are embarrassing, but Nikuko is in a league of her own. Yet,

her daughter Kikuko never judges her too harshly, because she understands her

better than even her mother realizes. Life dealt Nikuko a lot of

disappointments, but at least she has her daughter in Ayumu Watanabe’s Fortune

Favors Lady Nikuko, from Studio 4ºC and GKIDS, which screens nationwide

tonight (and opens Friday in select theaters).

Big-hearted

and big-boned Nikuko has a long history of getting involved with the wrong men,

who inevitably took advantage of her. The last was arguably the best of the bad

lot, so Kikuko sort of understood when her mother dragged her to his sleeping

fishing village-hometown, afraid he had fled there to take his own life. They

never found him, but they decided to stay and make a home there.

Nikuko

works for the gruff but protective Sassan at his seafood grill and they rent

his ramshackle houseboat. Boys are not really a factor yet in tomboyish Kikuko’s

life, but she is reasonably friendly with her fellow girls at school. In fact, she

is courted by two basketball-playing cliques, because of her height, but she is

uncomfortable committing to either side. However, her anxiety is probably

really coming from a fear Nikuko will uproot them again.

Despite

being a slice-of-life story (think of as a Japanese Beaches, but with

less weepy melodrama), Lady Nikuko features some wonderfully vivid

animation. The coastal village and surrounding environment sparkle on-screen

quite invitingly. (It is easy to believe this came from the same animation house

that brought us Tekkonkinkreet.) Ironically, there is a far more visual

dazzle in this film than Watanabe’s more fantastical Children of the Sea.

David Cronenberg is catching the Greek Weird Wave, filming his latest in the

ancient but economically depressed nation. Aesthetically, they are perfect for

each other. Body horror meets subversive, extreme anti-social behavior. Yet, according

to Cronenberg’s vision of the future, both the body and society are evolving,

but to what is yet to be determined in Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Future,

not the one from 1970, the entirely new and unrelated one that opens this Friday

in New York.

It

is not exactly clear how far into the future this film takes us, or where, but

the environment is vaguely Mediterranean, for obvious reasons. Cronenberg doesn’t

exactly pander to viewers during the prologue, in which a mother smothers to

death her son, for eating the plastic waste basket.

Those

are definitely Weird Wave vibes. Saul Tenser delivers the body horror, but he

calls it art. For years, his body has spontaneously generated new mutant organs,

which his partner Caprice surgically removes during their performance art

programs. Each organ is considered a work of art that the newly formed National

Organ Registry duly records. Not surprisingly, the Registry’s two employees,

Whippet and Timlin, are among Tenser’s biggest fans.

Lang

Dotrice also closely follows Tenser’s work. In fact, he offers Tenser a concept

for his next show: autopsying Dotrice’s son, Brecken, who was killed at the

start of the film. Dotrice leads a mysterious cult that has genetically modified

themselves, so they can only consume plastic waste. Brecken was the first of

their progeny to naturally develop their ability to digest plastic, but he

apparently creeped out his unevolved-human mother.

Cronenberg

definitely brings the gross and the weird, but the story and characters are a

bit sketchy. This is an idea film and a mood piece rather than an exercise in

story-telling to hold viewers rapt. However, the mood is pretty darned moody. Even

though this is the future, everything looks dark, decaying, and fetid, like it

could be part of a shared world with Naked Lunch, while the strange

surgical and therapeutic devices look like they were inspired by the designs of

H.R. Giger.

Viggo

Mortensen and Lea Seydoux are perfectly cast and do indeed create an intriguing

relationship dynamic as Tenser and Caprice. Cronenberg raises some challenging

questions about the roles they both play in creating art, particularly with

regards to the nature of authorship and intentionality.

Unfortunately,

characters like the two mechanics from a shadowy Vogt-like multinational

company, who are constantly servicing Tenser’s feeding chair and pain-relieving

beds could have stumbled out of dozens of uninspired dystopian films. (Frankly,

the sort of bring to mind the Super Mario Brothers movie, which is not a

good thing.) Beyond Tenser and Caprice, the most interesting character might be

Det. Cope of the new vice squad, who is trying to anticipate future crimes

against the body. Welket Bungue portrays his hardboiledness with subtlety not found

anywhere else in the film.