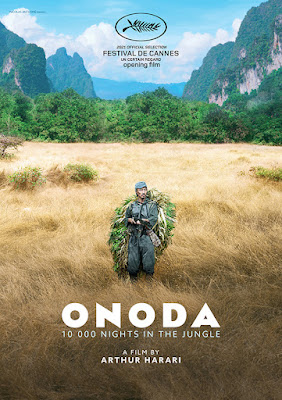

Hiroo Onoda helps prove why the atomic bombing of Japan were necessary to end WWII. He was the second to last Japanese soldier to lay down his arms, decades after the Emperor surrendered. Onoda and the final holdout, Teruo Nakamura became the stuff of tall tales and legends, but his story is in fact a tragedy. The sad futility of Onoda’s service is chronicled in French filmmaker Arthur Harari’s multi-multi-national co-production Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle, which screens as part of the 2022 New Directors/New Films.

Initially, Onoda was considered a washout, because his acrophobia prevented him from fulfilling his duties as a kamikaze pilot. However, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi gave him a chance for redemption when he recruited Onoda for training in guerilla resistance. Onoda is dispatched to Lubang in the Philippines, with the anticipation that it would soon fall. No matter what he might hear, Onoda and whatever troops he can hold on to are supposed to wage hit-and-run attacks against the Americans and our local Filipino allies.

Unfortunately, Taniguchi trained him too well. Few of the troops have Onoda’s will to fight, but his second in command, Kozuka is as dedicated/stubborn/incredulous/fanatical as he is. Inevitably, the numbers of their rag-tag group dwindle, until it is just gaunt and grizzled Onoda and Kozuka, but they still manage terrorize the local farmers on a regular basis.

In some ways, Onoda is an absurdist war film, not so radically dissimilar in terms of aesthetics from Apocalypse Now. Yet, it achieves a note of grace and redemption when a young, conscientious “tourist” journeys to Lubang, in hopes of bringing home the now nearly mythical Onoda.

Although more senior than a drill sergeant, Taniguchi, as played by Issey Ogata, ranks alongside Louis Gossett Jr. in An Officer and a Gentleman and R. Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket. Yet, one of the most fascinating developments in the film is the way Taniguchi is forced to face up to his former militarism.

Both Yuya Endo and Kanji Tsuda are brutally intense and frighteningly emaciated as the younger and older Onodas. The same is true of Yuya Matsuura and Tetsuya Chiba as young and old Kozuka, except maybe even more so. Yet, it is Ogata who really deserves award consideration (as unlikely as it might be) for his work as Taniguchi. He notably also played Hirohito in Alexander Sokurov’s The Sun, a film that would be interesting to compare and contrast with Onoda, because each are the work of foreign directors that critically examine Imperial militarism, but still reflect some sympathy for the Japanese.

Imagine a nation of Onodas. That could have been a reality, because the Imperial regime explicitly weaponized the entire population. Onoda sacrificed the best years of his life to a cause that was long lost. It makes Harari’s films one of the saddest, loneliest epics ever. Highly recommended, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle screens this afternoon (4/23) at the Walter Reade and Sunday (4/24) at MoMA as part of ND/NF.