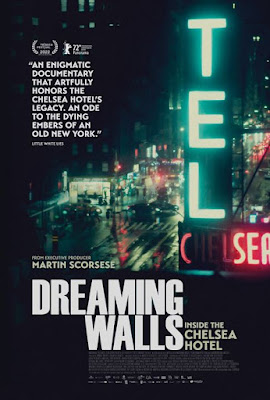

This documentary shows you just how hard it is to get anything done in New York City. After years of renovation intended to transform the Chelsea Hotel into the kind of luxury venue it was originally built to be, there is still no end in sight. As one resident notes, the Hudson Yards were completed during the time of the still unfinished renovation. At the peak of its Chelsea Hotel-ness, the brightest icons of art and literature stayed in residence there, as did the lowest of low lives. Maya Duverdier & Amelie van Elmbt focus on the surviving holdout residents, who mostly fall somewhere between the two in the documentary Dreaming Walls, which opens Friday in New York.

This is the second significant documentary dedicated to the Chelsea Hotel. The first was Abel Ferrara’s Chelsea on the Rocks, which captured the Chelsea institution’s grubby bohemian spirit. Duverdier and van Elmbt try to convey its artistic soul. Ferrara was more successful.

A lot of Dreaming Walls consists of fly-on-the-wall observational sequences, following longtime residents as they kvetch and complain. Janis Joplin and Dylan Thomas are mentioned in passing, but the film never delves into the infamous Sid & Nancy lore. Probably, the most interesting segments incorporate archival footage of accomplished but not necessarily famous residents like composer Virgil Thompson and painter Alphaeus Cole, whose work deserves more scholarly attention.

On the other hand, the endless griping of senior tenants gets tiresome. They clearly feel they have the right to live in Bohemian grandeur, paying minimal rent. Most of them have largely fond memories of the seedy, glory years, but those days are gone. Frankly, most of the people we see in the film look like they would be more comfortable in modern artists’ colonies or as 20/80 residents in new developments.

There are a number of impressionistic interludes in Dreaming Walls, but they rather conspicuously clash with the messy construction underway practically everywhere in the building. Honestly, just judging from the film, it is hard to understand the holdouts’ affection for the building or their motivation for staying.

Ferrara is not the greatest interviewer, but at least he knew the late Stanley Bard, the longtime owner-manager who set the hotel’s Bohemian tenor during his tenure. He also elicited a number of colorful anecdotes from former residents, such as Ethan Hawke, sometimes in spite of himself. It turns out, Ferrara has the definitive word on the subject, which is probably fitting.

In contrast, the approach of Duverdier and van Elmbt is too distancing, self-conscious, and determined to ignore the very stories anyone interested in a Chelsea Hotel doc wants to hear. There is also an attempt to critically address “gentrification,” but it is not persuasive. Not recommended, Dreaming Walls opens this Friday (7/8) in New York, at the IFC Center.