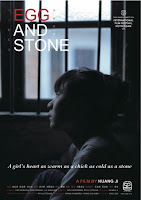

Interrupting an intensely personal, deeply emotional

film about sexual abuse with some organized thuggery would be embarrassingly crass

and heavy-handed, but that is exactly what happened to Huang Ji’s film at the

Beijing Independent Film Festival. Halfway through her screening, the power to

the maverick-dissident fest was not so mysteriously cut. Inspired by her own

unfortunate experiences, Huang Ji shines a spotlight on contemporary Chinese

gender inequity in Egg and Stone (trailer here), which screens as

part of Cinema on the Edge, the retrospective tribute to the Beijing

Independent Film Festival.

Honggui was only supposed to stay with her

aunt and uncle for two years, but she has spent the last seven in their

hardscrabble Hunan village. Her aunt clearly resents her continued presence,

but her uncle is suspiciously fine with it. The fourteen year-old is indeed

pregnant, putting her in a precarious position within the judgmental society.

However, if she has a boy, it becomes a marketable commodity.

For Honggui, life is profoundly complicated by

two pernicious social dynamics, the illegal urban migration caused by extreme

rural poverty and an intractable cultural preference for boys over girls. Of

course, the Party is not eager to discuss any of this, particularly in light of

their only slightly relaxed One Child policy.

Still, Egg

is far from an overtly political film, yet it is still one of the bravest

films programmed during Cinema on the Edge. Huang Ji shot the film on location

in the same provincial town where she herself was sexually abused by her uncle.

She also has a different uncle play Honggui’s predatory guardian in Egg.

There are powerful images in Egg, but the film’s preoccupation with

menstrual blood becomes increasingly unsettling, in the wrong way. Frankly, it

distracts from the viscerally honest performance of first-time thesp Yao Honggui

as her namesake. She really looks like a barely teenaged girl who has had to

grow up quicker than she should. Yet, despite everything Yao does to pull us

into her heart and headspace, many of Huang Ji’s coldly severe stylistic

choices push us away.