Winny was sort of like a Japanese Napster, but it was originally envisioned

for more Wikileaks-style purposes. At least that was the defense offered by the

creator’s lawyers when he was put on trial for facilitating copyright

infringement. Technically, Isamu Kaneko is on-trial, but so is his creation in

Yusaku Matsumoto’s Winny, which screens as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Kaneko

fits every programmer stereotype, making him a difficult defendant for the old

school judges to relate to, or understand. Fortunately, Toshimitsu Dan gets him

enough to formulate his defense, while also communicating persuasively. Dan

also has the benefit of Akita Masashi, his firm’s crafty senior partner, who is

serving as co-counsel.

Of

course, the naïve Kaneko makes things much more difficult for them, by signing

pre-written statements the Kyoto police assure him they he can change later. The

case is strange in many ways, since it focuses on Kaneko instead of those who

actually pirated copyrighted works. However, it is not lost on anyone that the

same police precinct is concurrently denying corruption charges prompted by

financial records distributed anonymously via Winny.

During

the trial, the word “proliferate” takes on great significance. In fact, these

court room scenes and all the trial prep are really crisply executed. Unfortunately,

Matsumoto and co-screenwriter Kentro Kishi never fully integrates the police

slush fund subplot with the rest of the film. It is a shame, because Yoshioka

Hidetaka is excellent portraying Senba, the police whistleblower.

It gave fans our first look at Boba Fett in action and we loved it. The

rest of the notorious Star Wars Holiday Special became a joke that

George Lucas tried to bury. Nevertheless, its legend lives on. Jeremy Coon and Steve

Kozak do not exactly rehabilitate the holiday special, but they help fans

appreciate the times and circumstances that gave rise to it in the documentary A

Disturbance in the Force, which had its international premiere at the 2023 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Ever

since it aired (for one-time only) in 1978, the holiday special has become

an easy Simpsons-style punch-line: “like The Star Wars Holiday

Special, ‘nuff said!” It is easy to see why. There is “comedy relief” from

Harvey Korman (in drag), Bea Arthur, and Art Carney. Plus, Diahann Carroll did a

Donna Summer-esque disco sex ode. Yet, everyone admits the original cartoon, “The

Faithful Wookie,” rendered in a style deliberately reminiscent of Moebius, was

pretty cool, especially because it included the very first in-world appearance

of Boba Fett. In fact, it is the only part of the special available on Disney+.

According to Jon Favreu, it even influenced The Mandalorian.

As

a young fan, I definitely remembered that cartoon and the design of Chewie’s Wookie

family home. The rest just went in one ear and out the other. Having seen the Donnie

& Marie Star Wars episode (which Donnie Osmond discusses at length in

the doc) and the Star Wars Muppet Show episode, I must have intuitively

understood this is just how late 1970s network TV treated a blockbuster sf

franchise, which is largely the point of Disturbance.

Coon

and Kozak talk to a lot people involved in the making of the special, including

Steve Binder, who also directed the Elvis Comeback Special. Since this

was the pre-VCR era, Lucas and the studio worried fans might forget the first

film, which is why the original cast started appearing on variety shows, before

filming the special. Apparently, there was a bit a power struggle between the

Lucas camp and the network camp, but as the troubled production dragged on,

more and more Lucas people were replaced by network veterans.

Even though they had Godzilla and Gatchaman, Star Wars still blew the

minds of Japanese science fiction fans when it opened in 1978 (in Japan). That

is especially true for Hiroshi. He aspires to remake Star Wars for his

high school arts festival, but the project evolves into something more original

and more personal in Kazuya Konaka’s Single8, which screens today as

part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Hiroshi’s

first film was a Jaws “homage” called Claws that technically

pre-dated Grizzly, but he still finds it embarrassingly amateurish by

his current standards. He has been obsessively trying to recreate the opening Imperial

Destroyer scene in Star Wars—notice how nobody calls it “A New Hope” in

1978—with the help of his pal Yoshio. Since nobody has a better idea, they pitch

their remake to their class, for the school’s arts festival. Their teacher, Mr.

Maruyama, is reasonably receptive, but he encourages them to create their own

story, with a message that will speak to their classmates.

With

input from Sasaki, another fannish classmate, they brainstorm the plot of Time

Reverse, in which aliens alarmed by Earthlings’ destructive tendencies make

time run backwards, so humanity can fix its mistakes. The only two people

unaffected are a teen couple, whose relationship is on the rocks. For Hiroshi,

the greatest advantage of their new story is that his longtime crush Natsumi

might be interested in playing the female lead.

Although

Hiroshi and his friends are initially motivated by their Star Wars love,

Single8 (Japan’s equivalent to Super8) has far fewer references than

Patrick Read Johnson’s 5-25-77. It is also considerably livelier and

much less whiny. Frankly, a better comparison film would be the original One Cut of the Dead, because both films are such affectionate tributes to the filmmaking

process.

Oda Nobunaga's wife Nohime did not think much of him at first, but she

became his Lady Macbeth, driving his ambitions, before settling into an Eleanor

Roosevelt role as a trusted advisor. At least that is how a new film commissioned

to celebrate the Toei film studio’s 70th anniversary presents her.

The mysterious Nohime finally gets equal screentime with her legendary husband

in Keishi Otomo’s The Legend & Butterfly, which screens tomorrow as

part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Nobunaga

and Nohime only married to make peace between their clans. The courtship was

rocky, to say the least. Nohime only agreed, because she intended to kill him, just

like her previous husbands. However, she must accept his protection when her

clan is attacked. Of course, Nohime wants revenge, but she pushes Nobunaga to

take more when he emerges as one of the most powerful Daimyo in Japan.

For

a while, L&B is like a Chanbara Mr. & Mrs. Smith, because

they are both serious butt-kickers, especially her. However, as the film takes

on epic scale, Nobunaga becomes the more prominent force. Yet, their

relationship also continues to evolve, and in some ways, deepen.

Considering

how little was documented on Nohime’s life, beyond her status as Nobunaga’s

wife, screenwriter Ryota Kosawa’s speculative attempts to fill-in the blanks

are quite convincing. He creates a compelling character, whom Haruka Ayase

brings to life quite vividly. By far, she is the most compelling figure in the

film. Kosawa and Otomo definitely present her from a modern, pseudo-feminist

perspective, but Ayase makes her credible as a woman of her era and relatable to

contemporary viewers. She also looks impressive during her several action

sequences.

If you can’t laugh at family, who can you laugh at? Of course, they still

have to be funny. The Phams are very hit-or-miss when it comes to comedy, but

boy do they try hard to bring the yuck-yucks. There is a lot of running around

and complaining in their suburban Canadian neighborhood, but each problem is

resolved in about twenty-two minutes by the diverse cast in creators Andrew

Phung & Scott Townsend’s Run the Burbs, which premieres Monday on

the CW.

Run

the Burbs is

shot in Ontario, but it is based on Phung’s Calgary suburb. Wherever it is, it

is definitely Canadian, which is what we are coming to expect from CW shows,

especially during the writers and actors strikes. Phung plays Andrew Pham, a

stay-at-home dad, who raises his abrasively woke teen daughter Khia and geeky

pre-teen son Leo, while his wife Camille makes money doing her “entrepreneurial”

thing. Of course, Khia has some sort of trendy alphabet sexuality, so they can

avoid the trouble of writing a complex persona for her.

There

are times when the writing appears poised to make sharp satirical commentary,

but it always backs off at the last minute. For instance, in the pilot episode “Blockbuster,”

the neighborhood block-party is in danger of cancellation, by the officious

paper-work-obsessed community-association president, but it down-shifts into a

cheesy Fast & Furious parody (in which Camille takes on a

street-racer for his party permit) rather than seriously skewering the buzzkill that

is bureaucracy.

Likewise,

“Heatwave” sees Khia accept a mural commission at their favorite bubble tea store,

only to squander it with a highly politicized and massively inappropriate monstrosity.

It is a great set-up to skewer the woke mentality, but the toothless follow-up

mostly consists of some apathetic shrugs.

Kenji Miyazawa was poorly served by his publishers in his lifetime, but anime

and manga adaptations made him a posthumous giant of Japanese literature. His

life was tragically short, but his father believed in his talent, at least most

of the time. The Miyazawas’ close but sometimes difficult father-and-son relationship

is the focus of Izuru Narushima’s Father of the Milky Way Railroad,

which screens tomorrow as part of this year’s Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

Masujiro

Miyazawa is a reasonably prosperous country pawnbroker, like his grouchier

father. He considers himself a contemporary man of the late Meiji Era, but Masujiro

still assumes his firstborn son will succeed him in the family business.

However, as Kenji grows older and more headstrong, he envisions other destinies

for himself, including as an agricultural expert and as acolyte in a severe

Buddhist sect.

Of

course, writing was his true calling, but it takes a family tragedy to

re-awaken his fantastical creativity. Throughout it all, Miyazawa’s father

continues to support him, despite often losing patience in his flaky behavior.

In

fact, their relationship is surprisingly believable. There is a lot of

tear-jerking in Narushima’s film, but he and the cast earn their big emotional

pay-offs. Sadly, this is the kind of deeply felt family drama the American film

industry cannot be bothered with anymore. There is no secret abuse to expose or

power dynamics to subvert. It is just a family, relatively progressive for its

time, dealing with the challenges and disappointments of life.

In the mid-1990s, Ebay became the place for collectors. Everyone who was

buying LPs largely have seen their purchases hold their value, because the

music in the grooves has intrinsic value. That has not been the case for Beanie

Baby collectors. Crypto cannot compare, yet, to the boom and bust of the little

“under-stuffed” plushies. Directors Kristin Gore and Damian Kulash show how it

happened from the perspective of three women who had the mixed fortune to be

close to the company founder in The Beanie Bubble, which premieres today

on Apple TV+.

Ty

Warner sort of had the original vision for more “posable” stuffed animals, but

he was also a manipulative user. At least that is the conclusion his former “partner,”

“Robbie” (based on Patricia Roche) comes to. For a while, he manages to replace

her with Maya Kumar (transparently modeled on Lina Triveti), who literally

joined the company as an intern answering the phones. However, she had an

inkling of the potential for internet marketing way before it was a standard

thing.

Kumar

also has the brilliant idea to play up the limited nature of the mini-sized

plushies. Fortuitously, some of Warner’s designs were starting to catch on,

especially those he developed with input from the woman he is romancing and her

two daughters. In fact, from Sheila’s perspective (sort of Faith McGowan), her

girls did most of the work. However, he sufficiently dazzles them with extravagant

gifts, so they do not think about things like rights or credits.

Beanie

Bubble is

much like Matt Johnson’s BlackBerry, in that both persuasively and

dramatically show what each company did right and what they did wrong (though BlackBerry

is definitely the superior film). On the other hand, Beanie Bubble is a far

more entertaining and more up-tempo viewing experience than the HBO doc Beanie

Mania. Regardless, it is fascinating to see how the Ty company rode the

original internet wave. Yet, it so conspicuously stacks the deck against

Warren, it cries out for an epilogue from his perspective, to give some sense

of balance.

Gore

and Kulash constantly flash backwards and forwards, for the sake of being hip

and stylish. They always immediately identify the year, so it is confusing, but

it sometimes fractures the flow. However, it is certainly an aptly colorful

production, suiting its subject.

The humble pencil is a symbol of freedom. It is an instrument of a free

press and Milton Freidman famously used it to illustrate the benefits of a market

economy and the division of labor. He is right, no one person can make a

pencil, but there is a grim looking pencil factory in the Russian Karelian

village Antonina Zolotareva moves to, in order to be closer to her imprisoned activist

husband. Zolotareva is no Jaime Escalante, but she is the most conscientious

teacher her new students have ever had in Natalya Nazarova’s The Pencil,

which premieres today on OVID.tv.

Zolotareva’s

husband was a prominent artist, whose work often criticized the Putin regime

(maybe that part is not explicitly stated, but it is clearly implied). Unfortunately,

it is all too evident during Zolotareva’s first visit, his spirit has been broken.

Nevertheless, she has already committed to living in the nearby industrial

town. She too is a trained artist, so she obtains employment at the local

under-staffed public school.

Much

to her surprise, some of Zolotareva’s students have talent, but the school

bully, Misha Ponomarev, does his best to disrupt her classes. Since his brother

is a local gangster soon to be released from prison, most of Zolotareva’s

colleagues turn a blind eye to his thuggery. Perhaps foolhardily, Zolotareva

challenges Ponomarev’s authority, so he responds with greater violence,

particularly against the under-sized Dima Demkin, her most promising pupil.

As

a side note, I will no longer cover commercial releases from China, Hong Kong,

or Russia, because the established film industries have been so thoroughly

compromised by the CCP and Putin regimes. That clearly does not apply to this

film. It might have had a domestic Russian theatrical release, but it paints a

very different picture that what RT propaganda projects. In fact, it depicts

a profoundly corrupt society, in which people regularly ignore the violence around

them. Watching The Pencil, it is easy to understand why so many Russians

blandly accepted Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

If you have read your Hawthorne, you should be wary of a house with many

gables. Parker certainly should have, being a writer. Instead, he and his wife

are initially charmed by all the old love letters they find hidden inside. That

also should have rung some alarm bells too, but they don’t suspect the

supernatural until it is too late in screenwriter-director Greg Pritkin’s The

Mistress, which releases tomorrow in theaters and on VOD.

At

first, Parker and Madeline are thrilled with their new Queen Anne house (mostly

bought by her, because, you know, he’s a writer). They think the old plate

camera they find is charming and the former occupant’s love letters fascinate

them. They remain oblivious even when a friend suffers a freak accident. Then

Parker starts seeing a mystery woman in the house. Initially, he assumes it is

his old stalker, but she reveals herself to be the spirit Rebecca, who committed

suicide in the house a century prior, after her married lover rejected her.

The

Mistress has

some nice bespoke period trappings, like the plate photographs and love

letters, but Pritkin’s basic narrative is very familiar stuff. Most horror fans

have seen the same before, but oftentimes better.

Still,

there are several nice touches. Parker listens to Blue Note-era Herbie Hancock,

which is something. It is also pretty mind-blowing to see Rae Dawn Chong

playing Madeline’s mom—and she is good, as fans would expect.

Evidently, Travolta had it easy in Face/Off. His mind-body swap was with Nic

Cage, who was crazy, but not nearly as sinister as this Korean serial killer. Det.

Choi Jae-hwan had been pursuing Cha Jin-hyuk, until he wakes up inside the

psycho’s body. It is obviously inconvenient, but there are also potential

advantages when it comes to catching Cha’s accomplices in Kim Jae-hoon’s Devils,

which had its North American premiere at the 2023 Fantasia International FilmFestival.

Cha

is the leader of a band of dark-web snuff film sickos, so yes, he is really

bad. They have long eluded Choi, even killing brother-in-law, a fellow cop, during

the prologue. Choi wants him bad, so he pursues him at all costs when they

receive an anonymous tip. However, both Choi and Cha disappear into the forest,

leaving the cop’s protégé-partner Det. Kim Min-sung completely baffled.

A

month later, they mysteriously re-appear. The man who looks like Choi claims to

have no memory of the last few weeks, whereas the man who looks like Cha wakes

up in the hospital, knowing he is in fact Choi. He also realizes his family is

in serious danger from his nemesis.

It

all sounds like Face/Off, but its not. Devils turns out to be

much more sinister and devious, but the big secret holds up incredibly well, at

least by high-concept thriller standards. Arguably, Devils turns out to

be more believable than that John Woo film it so readily brings to mind.

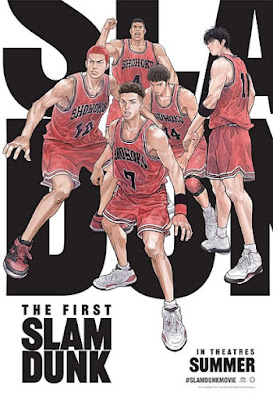

Do you miss the joy of basketball, before the NBA became consumed with the

pursuit of money from China? Ryota Miyagi and his teammates do not necessarily

like each other, but they play with a pure love for the game. Despite their talent,

nobody gives Okinawan students much of a chance against the defending Japanese

high school champions, not even their fans, in Takehiko Inoue’s The First Slam

Dunk, an animated adaptation of his manga, which screens as the opening

night film of the 2023 Japan Cuts Festival of New Japanese Film.

As

we see in flashbacks, Miyagi idolized his older brother Sota, who was one of

the top basketball prospects in Japan. Tragically, Sota was lost in a boating

accident, devastating Ryota. As a tribute to his older brother, Miyagi

obsessively pursues his hoop dreams, even though his single mother has her reservations

regarding the emotional toll.

Throughout

their game against Sannoh, Miyagi keeps flashing back to memories of his

brother. He also revisits some of his first encounters with his Shohoku teammates,

like their outside shooter, who was once a bully, but Miyagi won him over, by

taking his worst beating like a man.

Miyagi

is quick, but undersized, so he struggles against Sannoh’s press. Their big man

also gets into the head of Shohoku’s center. However, Miyagi’s Zen-like coach

has faith and a knack for making the right moves.

In the future, you still must pay your taxes. Death is a different matter—depending

on the circumstances. A quasi-government agency can resurrect anyone who dies

an untimely death, as long as they digitally backed themselves up within the

last forty-eight hours. Legally, they cannot use a file more than two days old.

There are practical scientific reasons for that, but they will be violated

anyway in Robert Hloz’s Restore Point, which had its world premiere at

this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival.

Nobody

dies, if they take reasonable precautions. However, there are those who feel taking

so much risk out of life devalues the experience of living, somewhat like in Tony

Aloupis’s better-than-you-might-think I am Mortal. Police detective Em

Trochinowska has a bone to pick with them, particularly the terrorist group

River of Life. They killed her husband, after holding him past the forty-eight-hour

mark.

Apparently,

they also just murdered the scientific director of Restore Point, David

Kurlstat, and his wife, after sabotaging their back-ups. However, Trochinowska unexpectedly

gets the benefit of Kurlstat’s technical expertise when she discovers Restore

Point illegally revived the scientist with a six-month-old bootleg. Unfortunately,

there is a bit of a mind-body disconnect, which makes the new imperfect copy

twitchy and nauseous.

It

has been a while since there was a new Czech science fiction film, even though

the Czechoslovakian film industry released many moody sf classics in the 1950s

and 1960s, such as Ikarie XB-1. In some ways, the dystopian Restore

Point very much feels like a throwback to that era. Hloz’s future urbanscape

is particularly impressive, taking design-inspiration from the real-life

postmodern structures of Shanghai and Dubai.

During times of war, a good internet connection can pass on valuable intelligence

and document war crimes for the world to see. Katya had something like the

latter in mind when she volunteered her tech savviness to the cause of Ukraine’s

defense, but she becomes determined to reunite the former owner of her used

laptop with his young son in Yelna Strelnikova’s Stay Online which

world-premiered at the 2023 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Apparently,

there is still some life in the “Screenlife” concept of films like Timur

Bekmambetov’s Profile and Aneesh Chaganty’s Searching. The minimal

set requirements helped facilitate the film’s production—billed as the first

feature initiated and completed since Putin invaded. Putin also supplied the realistic

war conditions seen throughout the film.

Katya

is struggling to find a suitable way to respond to the war raging around her.

Her brother Vitya is an armed volunteer with the defense forces, while her

American friend Ryan does humanitarian work in the field. They each want Katya

join their respective efforts, but she would rather share demoralizing information

on KIA Russian soldiers with their uninformed loved ones back in Russian.

She

also does some IT kind of work for Vitya’s unit, installing GPS tracking

software on donated laptops. Much to her surprise, she gets a Telegram message

from Sava, the young son of the laptop she is now working on. With the help of Vitya

and Ryan, she tries to track down his missing parents.

Viewers

need to steel themselves, because Strelnikova’s depiction of war is tragically

realistic. Bad things happen to good people, early and often. Arguably, Stay

Online is the most believable Screenlife movie yet, because a happy ending

is never guaranteed. It is also the most immersive Screenlife film, embedding

viewers into the war-zone, through FaceTime footage and the like, which is how

we have grown accustomed to witnessing combat.

According

to IMDb, Stay Online is Liza Zaitseva’s only screen credit to date, but

she is devastatingly convincing as Katya. It might have been partly a case of

involuntary method acting, given the war literally erupting around her. Yet,

she also expresses Katya’s grief and pain with visceral power. Viewers who do

not share her feelings must be dead inside.

Let this film be a lesson. Keep your car doors locked and your windows

rolled up. I have seen smart phones snatched out cars in traffic on the streets

of Rio, but the prospect of getting carjacked by Nic Cage is even worse. At

least it makes for an interesting ride in Yuval Adler’s Sympathy for the

Devil, which opens in theaters this Friday, after world-premiering at this

year’s Fantasia.

The

driver just wants to park, so he can rush to join his wife, currently

undergoing labor. Unfortunately, the armed “passenger” who jumps in his back

seat has other ideas. Apparently, he wants to take the driver out to a remote

desert air field for some sort of underworld reckoning. It is all totally

baffling to the driver, who steadfastly insists his name is David Chamberlain,

even though the Passenger is convinced he is someone else.

It

will be a proverbially bumpy night, especially when the Passenger shows his

willingness to kill anyone interrupting his cat-and-mouse game. The premise is

fairly simple, but the absolutely maniacal Nic Cage elevates it to nearly the

level of high art.

Indeed,

Adler shrewdly showcases the Cage Rage, trusting in its inherent appeal. Wisely,

Joel Kinnaman stays out of his way, opting for an understated slow burn

opposite the deranged Cage. Of course, any savvy film patron can guess the

answer to the is-he-or-isn’t-he “mystery,” but the gritty duo still keeps us

hooked.

When it comes to rebooting established franchises, the Japanese film industry

is much smarter than Hollywood. Just look at the “Shins,” or the “Shin Japan

Heroes Universe” movies: Shin Godzilla and Shin Ultraman. They

are all true to the spirit of the originals, but the effects have been

modernized—and pretty much only the effects (although Shin Godzilla also

savaged the supposed professionalism of government bureaucrats). Fans of the

long-running motorcycle tokusatsu TV series might be surprised by the return to

manga level of violence, but they will feel right at home with the rest of Hideaki

Anno’s Shin Kamen Rider (or Shin Masked Rider), which screened at

the 2023 Fantasia International Film Festival.

Poor

innocent biker Takeshi Hongo was kidnapped by SHOCKER (a KAOS or THRUSH-like

organization), who turned him into a grasshopper hybrid super-being. Ominously,

they intend to use the augmented hybrids (“Augs”) like him to destroy humanity,

because that will make Augs like them happy. In the long-run, they also think

it is in our own best interest, since we are such a miserable species. Ruriko

Midorikawa and her scientist father broke from SHOCKER, taking Hongo with them,

so he can fight to save humanity. It is a family affair, since SHOCKER will be

led by Ichiro Midorikawa, a butterfly-Aug, once he wakens from his cocoon.

Much

to the mild mannered Hongo’s surprise, he can hardly control his killer

instincts when he is suited up and using his Prana-fueled powers (prana being the

rough equivalent of Chi in the Shin universe). In contrast, Ruriko

Midorikawa is much more calculating and cold-blooded, but her powers are mostly

those of the mental kind. She always prepares. Unfortunately, their only allies

are the Anti-SHOCKER government agency, who are not particularly trust-worthy.

With

all its stunt-driving, Shin Kamen Rider is sort of like a cross between Ultraman

and Fast & Furious. While it is not as strong as the previous Shin

films, it at least manages to tell an entirely self-contained story in a

smidge over two hours, which is more than Fast X can say for itself.

In

terms of effects, the Shin-inized Kamen Rider represents a major

upgrade from the early 1970s cult classic. Sosuke Ikematsu and Minami Hamabe

are also very strong as the brooding Hongo and the detached and analytical

Midorikawa. Mirai Moriyama is pretty creepy as Ichiro Midorikawa, but the most

memorable villain is Spider-Aug, the first that Hongo fights.

In Canada, this show is sort of like Everyone Hates Chris or Young

Rock. Since comedian Mark Critch is not particularly well-known in America,

we can think of it as The Wonder Years with some Rush songs. Coming of

age is always hard, especially with an embarrassing family, but young Mark

Critch learns nearly everyone has an embarrassing family in Son of a Critch,

which premieres Monday on the CW.

The

Critch family lives on the outskirts of late-1980’s St. John’s, Newfoundland.

His father Mike (played by grown-up Mark Critch, who also narrates, like Daniel

Stern on The Wonder Years) is a gung-ho reporter for the local radio

station and his somewhat high-strung mother Mary boils all their food. Perhaps

his moody teen brother Mike Jr. is his least embarrassing family member.

However, sharing a bedroom with his crotchety grandfather Peter (“Pops”) is

definitely way up there, even though he is probably closer to Pops than his

parents or brother. Attending wakes to grade the food is one of their favorite things

to do together.

Regardless,

the best parts of Critch happen at the Catholic junior high school young

Mark is forced to attend. To say the Dean Martin-listening Critch is socially

awkward is an understatement, but he manages to befriend Ritchie Perez, the son

of successful Filipino doctors. Unfortunately, he is quickly bullied by “Fox,” one

of three thuggish red-haired siblings all known by their surname. She also has

a massive crush on Critch, which he reciprocates, even though he will not admit

it.

Based

on the first four episodes, young Critch’s relationships with Perez and Fox are

the best things going for the series. His rapport with grouchy grandpa is also

very likable, especially since the old dude is played by the legendary Malcolm

McDowell (try to forget how many times we have seen him naked in films like A

Clockwork Orange and Cat People). Listening to him kvetch with

Benjamin Evan Ainsworth, the young Mark Critch, is pretty amusing, particularly

in the funeral-focused second episode, “Lordy, Lordy, Look Who’s Dead.”

The

”Pilot” episode truly feels like a pilot, since it is literally Critch’s first

day of school. Still, the third act shows some of the chemistry developing

between Ainsworth and Sophia Powers and Mark Ezekiel Rivera as Fox and Perez. That

is where the charm and humor of the third and fourth episodes (“Cello, I Must

Be Going” and “Cucumber Slumber”) come from. That said, the digs at Catholic

school life and the portrayal of the nuns are mostly cliched and derivative

material.

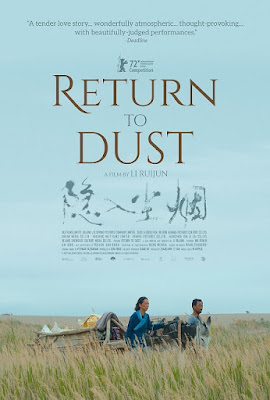

Usually, is great news when an indie release becomes a sleeper hit. However,

it got Li Ruijun’s hardscrabble film banned in China. Obviously, it is banned,

since it disappeared from theaters and streaming platforms, but there was no

formal explanation issued. It is not like you can ask these questions on

Chinese social media either. Perhaps the better question is how did Li’s

searing portrait of rural Chinese poverty and societal indifference ever get

approved in the first place? Life is bleak in Gansu (on the outskirts of the Gobi

Desert), as depicted in Return to Dust, which opens today in Brooklyn.

Ma

Youtie is a humble man, who is not comfortable with people. It is just as well,

considering how contemptuously his surviving younger brother treats him. Much

to his surprise, his disinterested family arranges his marriage to the disabled

and much abused Cao Guiying, largely so they can both be rid of them. They do

not have much choice in the matter, but they develop a supportive and

eventually loving relationship together, as they eke out a subsistence

dirt-farming living.

Ma

and Cao get no support from their families, so they essentially squat in

abandoned farm houses. Unfortunately, the provincial government has launched a

program to raze such derelict buildings, much like in Detroit. Ma also

literally has his blood sucked dry by the local oligarch, with whom he shares a

rare blood-type.

To

satisfy the censors for the film’s original release, Li tacked on an unconvincing

epilogue that bizarrely contradicts all the exploitation Ma and Cao endured and

the callous disregard of their community that viewers just spent over two hours

watching. This is a withering indictment of contemporary Mainland society, but

Li’s pacing is decidedly deliberate. It is easy to imagine CCP censors starting

the film and skipping ahead to the end, thereby missing the totality of the

couple’s Job-like suffering.

This

is not a charming little slice-of-life film, which makes its grassroots

breakthrough in China so surprising. It can be a tough go, but it is keenly

sensitive to its main characters’ trials and travails. Wu Renlin (Li’s uncle)

is an amazingly intuitive and expressive thesp. Technically, he is not a “professional”

actor, but this Li’s third film he has appeared in. The dignity and the sorrow

he conveys are absolutely devastating. Likewise, Hai Qing (a major star,

primarily in TV, but also from films like Sacrifice) will quietly

destroy viewers as Cao.

Don't go to Barbie. Watch the second season of this Philippines-set cop show

instead. Yes, they are vastly different, particularly in terms of their ethical bearings.

Barbie features a child-like rendering of China’s imperialistic “Nine-Dash Line,” which asserts their illegal claims to the waters and fishing rights of

the South China Sea, way beyond its borders. The studio claims their prop map

just coincidentally resembles the CCP’s notorious Nine-Dash Line, but has there

ever been a film that lavished greater attention on its art direction and

design details than Barbie?

In contrast, the third episode of Almost

Paradise’s second season directly addresses the dire economic hardships

experienced by Filipino fisherman as the result of China’s naval imperialism.

There are also ten new crimes for the somewhat unlikely trio of detectives to

solve in season two of creators Dean Devlin & Gary Rosen’s Almost

Paradise, which premieres today on Freevee.

If

Almost Paradise sounds vaguely familiar, season one premiered on WGN,

back in 2020. Now, it is a Freevee, show, but little else has changed, except

Alex Walker’s formerly high blood pressure. For health reasons, he retired from

the DEA and moved to Cebu, where he had fond memories from his first case. He

actually got healthier, despite working several cases with Mactan detectives

Kai Mendoza and Ernesto Alamares, sometimes reluctantly and sometimes through

his unwelcome initiative. Their boss, politically savvy (but not corrupt) Chief

Ike Ocampo is always eager for the benefits of Walker’s DEA experience—and contacts.

The ambitious Mendoza and the Zen-like Alamares are impressive, whereas Walker

is grizzled and burned-out, but his new Filipino friends steadily rejuvenate his

soul.

Almost

Paradise

is a very traditional throwback-style of detective show, in that all ten

episodes of season two can easily stand alone. There is a recurring villain, Vargas

“The Water-Boarder,” a drug lord Walker busted in the first season, but each

episode has its own self-contained arc. In terms of theme and tone, the series

should appeal to fans of Lenkov-verse shows like Magnum P.I. and Hawaii

Five-O, but it also incorporates Filipino and Cebuano culture in smart,

interesting ways.

The

first episode, “The Magellan Cross,” refers to a relic of early colonial times,

but it might be the weakest of the season, so keep going. “Breaking Badminton”

is indeed set in a dodgy badminton club, which is about as Philippines as it

gets. “A Fishfolk Tale” calls out the Chinese maritime grab by name, while

showing how the resulting hardships exacerbated tensions between two clans of

fishing families.

“Ghost

Month” (S2E6) might be the best episode, exploring local belief in “hungry

ghosts,” without completely undermining the supernatural themes with a pat “Scooby

Doo” ending. “All In” is a clever caperish installment, wherein Walker agrees

to test the security of a luxury casino owned by Ann Villegas, the heiress he

is trying to romance, while “Uncoupled” handles some creepy cult stuff pretty

well within its forty-some-minute time constraints, when Walker and Mendoza go

undercover in a New Age couples retreat.

It all goes back to Jaws, the movie that changed everything. It even

has its own behind-the-scenes Broadway play opening soon (unless there is yet

another strike). The idea of a summer “blockbuster” as we know it started with

its release. On the other side of the spectrum, Jaws also inspired a

whole school of cheap knock-offs. This documentary is all about the knock-offs.

Filmmakers and critics celebrate shark cinema in Stephen Scarlata’s Sharksploitation,

which premieres tomorrow on Shudder.

From

time to time, you saw sharks in movies before Jaws, particularly as the

pets and executioners of Bond villains. Obviously, the Spielberg classic took them

to a whole new level. Naturally, there is analysis of all three sequels, but a

lot of viewers might wish for more dish on the notorious Jaws 4: The Revenge.

Weirdly, it is almost like nobody who was in the film wants to talk about it

anymore.

Scarlata’s

coverage of Jaws 2 gives the first sequel some of the credit it

deserves. It really is a great film, but it gets unfairly lumped in with the next

two sequels, which were dreadful. (However, it is hard to believe Murray Hamilton

could still be the mayor. Honestly, Bill de Blasio must be the only other mayor

who did more damage to his town.) It is also important to remember “just when

you thought it was safe to go back in the water” was the constantly quoted tagline

for Jaws 2.

Scarlata

and company survey shark-specific imitators, as well as other sea predator

rip-offs, like Joe Dante’s Roger Corman-produced Piranha (both of whom

off on-camera commentary). There is coverage of reasonably presentable films

like Orca, Open Water, and 47 Meters Down. Unfortunately, the

French film Year of the Shark might have been too recent and not widely

enough screened to make the cut, but there is a good hard look at The Last

Shark, an Italian copy-cat that was so shamelessly derivative, Universal

successfully blocked its release. Of course, no films were more exploitative

than the Sharknado franchise.

In horror movies, when somebody hears a noise that other people say they

can’t, it is a sure bet someone is getting gaslit. Whether the scratching and

voices Peter hears are real or not might not be immediately clear, but it is

safe to conclude his parents are horrible. Unfortunately, they might not be the

only bullies and monsters he must contend with in Samuel Bodin’s Cobweb,

which opens Friday in New York.

Basically,

poor Peter is bullied at school and terrorized at home. Lately, he has been plagued

with nightmares and unnerved by noises coming from within the walls of his

room. At first, his parents tell him he is just making it up, but eventually

his dad Mark breaks out some rat poison, so he can act even creepier.

Just

about the only person who shows any genuine concern for Peter is new teacher

Miss Devine (a long-term substitute) who appreciates his sensitivity and

recognizes the warning signs of abuse. However, the principal counsels Devine to

stay aloof, while the voice in Peter’s walls offers dangerous advice.

Supposedly,

Cobweb (not a very descriptive or apt title) was partly inspired by Poe’s

“The Tell-Tale Heart,” but the film has a very different vibe, since Bodin and

screenwriter Chris Thomas Devlin clearly suggest there is something more

monstrous afoot than a psychotic unreliable narrator. In fact, there is—sort of—but

it is also extremely exploitative.

Regardless,

Lizzy Caplan and Anthony Starr are so deranged as Peter’s parents, they could

give Nic Cage (in Mom and Dad) a run for his money. Frankly, Caplan’s

big meltdown scene might even out-Cage-rage the master.

Usually, rural folk are more respectful of veterans. Creepy Perry thinks his

attitude is okay, because he considers himself a vet too, but Tess can tell he

never saw a day of combat. She is the real deal, so Perry should have given her

a wide berth. Instead, he and a few friends lay siege to her parents’ country

home, looking for a cache of drug money in Neil LaBute’s Fear the Night,

which releases this Friday in theaters and on VOD.

Nobody

in the family had been to their parents’ old place in years, but Tess’s judgy

sister Beth still wanted to have their little sister Rose’s bachelorette party

for there anyway. When they stop at the general store, Perry and his

knuckle-dragging sidekicks try to hassle the ladies, but Tess is having none of

it. When they get to the house, the care-takers seem a little dodgy. So much so,

Tess starts snooping around their cottage, overhearing some of their drug

business as a result.

When

night falls, Perry and his goons start shooting arrows into the house. Tess isn’t

sure whether the “caretakers” are with them or not. It is pretty clear Tess is

the only one the bachelorette party can count on, even though they have been

whining and snarking at her all night.

You

would never know from the pedestrian look and vibe of Fear the Night that

LaBute was once considered a major voice in drama and independent cinema. Then

the Nic Cage Wicker Man remake happened. This is generally watchable,

largely thanks to Maggie Q, who is a highly credible action star. However,

LaBute never cranks up the violence enough for fans of home invasion-revenge

horror and his gender warfare dialogue lacks the bite of his 1990s

career-defining work.

Grab a warm cup of Nongshim noodles and start meowing for no reason. Seriously,

there is no logical reason people make cat noises before Fantasia screenings

start, but by now, it is a tradition. They also have a tradition of screening

some of the most distinctive genre, cult, animated, and Asian films around.

There will be plenty of films to look forward to when the 2023 Fantasia International Film Festival opens this Thursday evening.

Usually,

Fantasia films are fun, which would seem to preclude anything depicting Putin’s

illegal invasion of Ukraine, but the backdrop of war makes a tense but fitting

setting for Yeva Strelnikova’s Stay Online. The first Ukrainian feature

produced since the invasion commenced, it uses the “Screenlife” techniques of

Aneesh Chaganty’s Searching and Timur Bekmembetov’s Profile.

Considering

how compromised the Russian and Chinese film industries have been by their

respective regimes, I no longer review any films their censors approve for

release. However, Victor Ginzburg’s Empire V holds the (happy?)

distinction of being banned by the Russian Ministry of Culture for its thinly

veiled satire of Putin’s oligarchs.

According

to the description, Robert Hloz’s Restore Point is the first Czech

science fiction in forty years, which is saying something. Fantasia is also

programming a mini-four film retrospective of Juraj Herz’s dark cult classics

(but not Cremator, maybe because it is too obvious).

South

Korea has produced some of the best thrillers of the last fifteen years,

especially historical thrillers, so Lee Hae-young’s Phantom looks like a

solid bet.

Sadly,

Nicolas Cage was supposed to be a special guest of the festival for Sympathy

for the Devil. Sadly, the actor’s strike ruined that for festival patrons,

but they are still screening his film.

Plus, there is even a

one-minute experimental Art Blakey short, “Visions of Blakey,” as well as many more

films ripe for discovery at this year’s eagerly awaited, live and in-person

Fantasia International Film Festival.

The Ravens are such a dumb hardcore band, they don’t get the Damon Knight (“To

Serve Man”) joke when a fan promises “my folks are having barbecue—they would

love to have you.” Unwisely, they drive her into the ruins of Epecuen, the

flooded Argentine resort city that remains in complete ruins. Just like in the

previous film, the Ravens fall prey to a grotesque Texas Chainsaw-like

family of homicidal freaks in Nicolas Onetti’s What the Waters Left Behind:

Scars, which releases tomorrow on VOD.

This

film is a lot like the first film, unfortunately, but it was helmed by only one

half of the Onetti Brothers. At least Luciano Onetti showed his support by

scoring the sequel and serving as associate producer. It is just as sadistically

brutal, but this time the Epecuen squatters are so violent and hostile, they

also display a tendency to turn on themselves. That could theoretically open a

window of opportunity for the Raven, but don’t get your hopes up.

Frankly,

Scars might even be tougher to slog through the just plain What the

Waters Left Behind. The first film maybe also made better use of the

shockingly bleak and powerfully cinematic Epecuen backdrop. Still, there are

some striking drone shots of the tour van crawling across the blighted

landscape.

There is no question horror movies have been ahead of the curve when it comes

to calling out bullying. That was what Terror Train was all about (the

original and the remake). No points for originality there and this film also

alienates potential viewers by equating anti-bullying with “wokeness.”

Seriously, who are the biggest crybullies on Twitter? It all goes downhill from

there in L.C. Holt’s Time’s Up, which releases Tuesday on VOD.

A

bullied high school student committed suicide in Pine Falls, but as the town

counts down to the New Year, most of the school’s students and faculty are

doing their best to not to deal with it. The exception is Jacqui, a local

muckraking journalist, who awkwardly happens to be married to the school

guidance counselor, Tony, whose guidance obviously failed the late Brendan. It

is super-awkward since their host, Gene the school principal, imposed the code

of silence on the faculty.

Jacqui

and Tony are about to bail, when Gene and the meathead wrestling coach Cliff go

out to investigate a “prankster.” It turns out the party crasher is a

slasher-psycho wearing a Father Time mask. According to the production synopsis,

Father Time will force them to participate in a horrifying “scavenger hunt.”

However, they are really just following a few bloody arrows to the town

library.

It is not like these kids had it easy to begin with. In many cases, their

alcoholic parents had yet to inquire regarding their status, even after Ukrainian

social services revoked their parental rights. Then their welcoming halfway

home in Eastern Ukraine was forced to evacuate when Putin launched his illegal

invasion. When the troops crossed the border, filmmaker Simon Lereng Wilmont had

already finished shooting his Academy Award-nominated documentary A House

Made of Splinters, which airs Monday on PBS stations, as part of the

current season of POV.

Unlike

Eastern Front and 20 Days in Mariupol, House Made of Splinters

is not a war film, but the Russian dirty war in Donbass was indeed

stretching Ukraine’s already strained resources for social services. Frankly,

the three kids Wilmont focuses on are lucky to be there. Longtime educator/case

workers Margaryta Burlutska and Olga Tronova provided a sheltering environment

for the children, who were suddenly dealing with abandonment issues on top of

everything else.

The

Lysychansk Center was sort of a way station. Eventually, their residents either

leave for a state-run orphanage or foster parents recruited by Burlutska and Tronova.

Generally, fostering is the preferable option, but it essentially means the

foster children have given up hope for a further life with their dysfunctional

birth parents.

The

three focal children all must come to terms with that reality, which is

definitely some very real-life drama. It is also very depressing. However,

thanks to Burlutska and Tronova, some of the kids have relatively happy endings—at

least until the Russians invade.

They are a bit like Frederic Henry in A Farewell to Arms, but the war

is happening in their own country. For them, volunteering as a medics and

ambulance drivers was the only way they could serve during the war. Many started

in the Donbass region as early as 2014 and they continued to serve following

Putin’s full invasion, despite some being judged “unfit” for armed combat (due

to health reasons). Medic Yevhen Titarenko captures a country that is

remarkably unified, despite being under constant fire in Eastern Front,

his eye-witness documentary (completed with the editorial input of “co-director”

Vitaliy Mansky, the acclaimed documentarian exiled to Latvia), which premieres

today on OVID.tv.

You

will definitely see some things driving an ambulance around Kherson and

Kharkiv. That is why Titarenko started documenting the horrors he witnessed,

employing hand-held devices, smart phones, and body cams. Much of what he

captured is horrifying. Yet, some of the quiet moments are even more telling.

In

between their emergency calls, Titarenko and his fellow medics, relax, chew the

fat, and even celebrate being alive together. Many have similar stories, especially

those who hail from families with strong Russian connections. At first, they

were the odd ones out for supporting the Maidan protests. However, after Putin’s

illegal invasion, their parents and grandparents have become ardent Ukrainian

patriots. Their anecdotal evidence suggest Putin has ironically unified the supposedly

fractious Ukrainians—against Russia.

Eastern

Front is

a powerful and bracing film. However, it might unfairly suffer in comparison if

seen soon after Mstyslav Chernov’s jaw-droppingly harrowing 20 Days in Mariupol.

Yet, it has other merits, very definitely including the medics’ thoughts on

Ukrainian unity and Russian propaganda. Nevertheless, Titarenko’s concluding dash

through a war-zone can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Normandy landing in Saving

Private Ryan.

Ironically, a zombie apocalypse breaks out while a film crew is shooting a zombie

movie. But wait, there’s more—as those who have seen Shinichiro Ueda’s One Cut of the Dead already know. However, this is sort of a remake and also

sort of a sequel. Apparently, it all transpires in a universe where One Cut exists,

but the production is plagued (so to speak) by similar problems. It isn’t easy

directing zombies in Michel Hazanavicius’s Final Cut, which opens today

in New York.

This

time around Higurashi doesn’t look like a Higurashi, but he is just as

deranged. Quite irresponsibly, he has invoked a WWII-era zombie curse to illicit

more convincing performances from his beleaguered cast. They too have distinctly

Japanese names, despite speaking French. All will be explained eventually.

It

is interesting to watch Final Cut, for the “first time,” while knowing

the big twists. It allows fans of One Cut to appreciate the ways

Hazanavicius tweaked the material and how he stayed faithful to the spirit of

the original film. Reviewing three similar takes on Invisible Guest was

probably one too many, but Hazanavicius’s clever in-film references to One

Cut help differentiate Final Cut. In some ways, they also make the

French remake/sequel/side-film even nuttier.

Romain

Duris and Berenice Bejo are terrific as the Higurashi the director and Natsumi

the make-up artist. They sort of play against type—and then they don’t—but they

both use their winning screen charismas to full effect. Lyes Salem and

Jean-Pascal Zadi are also very funny as the producer and composer-sound

designer.