Periodically, there are campaigns to revive the lost practice of letter writing. This

film could be part of that effort—and it makes a compelling case. It also

represents the road rarely taken by video game film adaptations. It is inspired

by Kadokawa’s “visual novel” mystery game, but even faithful players might not

realize the connection if they weren’t informed by the opening credits. Yet,

Sonja O’Hara’s Root Letter deserves credit for being its own thing when

it releases tomorrow in theaters and on-demand.

Carlos

Alvarez is the hard-working son of an immigrant maid in Oklahoma and Sarah

Blake is the frustrated daughter of an opioid-addicted single mother in Baton

Rouge. They have very different tastes in music, but they find they can relate

to each other when assigned to be pen pals, through their high school English classes.

In fact, they keep exchanging letters, even after the project ends—and then

Blake goes quiet.

Alvarez

could tell something was very wrong from the last letters he received, so he

drives to Baton Rouge looking for her. It will not be easy, since he does not

even know what she looks like. Starting with her school contact info, Alvarez

tracks down her deadbeat fair-weather oxy-addled friends. They claim to know nothing,

but the way they say so holds a great deal of menace.

Root

Letter is

about as slow and brooding as a film can get and still be considered a thriller,

but that is arguably a neat trick to pull off. O’Hara and screenwriter David

Ebeltoft have a great deal of compassion and sympathy for their pen pal

protagonists—and they are relatively forgiving of hardscrabble world they

inhabit. Nearly every character in this film is a victim to some extent—the

question is how they respond to their circumstances.

Still,

it probably wouldn’t have killed O’Hara to stir the pot a tad more vigorously.

However, she gets some great work from her young cast. Danny Ramirez (whom the

press materials are eager to remind us played Fanboy in Top Gun: Maverick,

which is definitely a seriously cool credit) brings an old school understated

film noir intensity to the film as Alvarez.

In Manhattan and Los Angeles, we have progressive district attorneys,

who proudly refuse to prosecute criminals. People no longer feel safe in those

communities, which also happen to be major hubs of film production. Consequently, you

can expect a major boom for home invasion horror, like this film. In this case,

writer-director Duncan Birmingham tries to soften the blow with some gun

culture criticism, but the fact remains Margo and Adam are not safe in their

own home, just like the rest of LA. It is their turn to deal with the

lawlessness in Duncan Birmingham’s Who Invited Them, which premieres

Thursday on Shudder.

Technically,

Tom and Sasha did not “invade.” They crashed Adam’s house-warming party. Margo

really doesn’t feel like it is her party too. That reflects some of the

fissures in their marriage the uninvited guests will exploit. After all the real

guests leave, the couple pops out of the bathroom, claiming to be the next-door

neighbors. They seem hip and connected, so Adam instinctively cozies up to

them. Both Tom and Sasha have a knack for pushing their buttons, so for a while,

it feels more like a Polanski film than Last House on the Left. Things

get super uncomfortable, but the threat of violence is not imminent (but

perhaps implied).

In

fact, the verbal sparring is clearly the part that interests Birmingham,

because when the film reverts to the violent business at-hand, it follows the

usual, uninspired, rote pattern. He also wraps it up as quickly as possible,

only pausing to show a firearm wielded in a way that would disgust any actual

gun owner.

Despite

Birmingham’s labored efforts, Who Invited Them still makes a persuasive case

for gun ownership. There are dangerous, evil people out there, whom Angelinos

have to face on their own. Of course, our DAs would offer victims the chance to

face the psychopaths who duct-taped them up in group therapy “Restorative

Justice” sessions, rather than sending to prison. Yet, somehow, that probably

would not be much of a “healing” experience for Margo and Adam, after what they

endure at the hands of Tom and Sasha.

If

you can’t afford the Stranger Things pinball machine, you can at

least read this book instead. In it, a trio of Eighties kids encounter

the pinball equivalent of the Polybius arcade game, but instead of Men in

Black, it runs on black magic. The scrawniest of the three falls victim to its

power, but his other two friends will not uncover the truth until the 1990s in

Sara Farizan’s YA novel, Dead Flip, which goes on-sale today.

Maziyar

“Maz” Shahzad, Corinne “Cori” O’Brien, and Sam Bennett had always been inseparable,

united by their geekly passions, but they were on the verge of the age when

their coed friendship would get awkward. Halloween 1987 might have been their

final time trick or treating together, even if Bennett had not mysteriously

disappeared that night. Upset that his friends had opted for a party with the

popular kids instead of visiting more houses, Bennett was drawn to the newly

refurbished pinball machine at their favorite convenience store.

Shahzad

also had a weird physical reaction to the Wizard-themed machine, but it really

got its hooks into Bennett. Somehow, it made the young boy disappear. At least,

that is what Shahzad always thought, but he couldn’t really verbalize the

suspicion, because it would sound crazy. Instead, the guilt he carried affected

his grades and his emotional well-being. He and O’Brien drifted apart,

especially after he transferred to a new school. By chance, he and O’Brien bump

into each other at the mall in 1993, which providentially reawakens their

memories of 1987, just in time for a major new development in the case. Of course,

it is too crazy for them to bring to parents, so they will have to deal with it

together and with the help of a few of their new friends.

Occasionally,

Farizan uses turns of phrase that would have sounds out of place in either the

golden age of the 1980s or the bad old 1990s, but there is a good deal of on-target,

era-appropriate nostalgia (plenty of Monster Squad references, but no

Cannon action movies). Generally, she accurately captures the tone of a

childhood without social media. The Stranger Things comps are

unavoidable, but the Polybius urban legend was much more of a model for the

story.

Yet,

it is the relationship between the old friends and their new friendships that

will keep the younger intended audience reading. At times, O’Brien and Shahzad’s

devotion to the imperiled Bennett is quite poignant. It is also rewarding to

see these central characters growing up and taking responsibility for their lives,

especially under such extraordinary circumstances.

Unfortunately,

there are a few interior monologues from O’Brien complaining about the unfair

social demands of high school life for an in-the-closet young woman like that

go on a little too long. Yet, that kind of content is demanded by the YA literary

gate-keepers these days, and they don’t appreciate subtlety, so there it is. At

least regular readers can blow through them relatively quickly and get back to

a good story.

And it is a good

story, nicely told. Perhaps most impressively, Farizan nicely handles the

constant flashbacks and flashforwards, skillfully using them for dramatic

effect. Recommended for teens who enjoy retro 19980s horror and Gen X parents, Dead

Flip is now on-sale wherever books are sold.

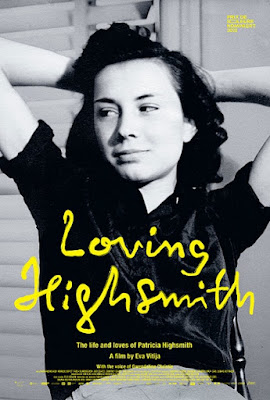

This is just a reminder Patricia Highsmith also wrote books. It will be

important to keep that in mind during this documentary, because it relentlessly

focuses on the private life she wanted to keep private. As a result, Highsmith

most likely would have been horrified by Eva Vitija’s Loving Highsmith,

which opens Friday at Film Forum.

Throughout

her life, Highsmith kept journals she did not want other people to read. In

fact, she wrote large notes at the beginning of later journals emphasizing what

she wrote within was for her eyes only. Vitija excerpts those diaries

extensively throughout Loving Highsmith.

For

the first six years of her life, Highsmith lived with her grandmother in Texas

and consequently always retained some sense of being a Southerner. In fact, you

can somewhat see a Flannery O’Connor sensibility in her work, especially in

regards to the dark side of human nature. The Texas relatives Vitija interviews

seem relatively accepting of her sexuality, but they are still a bit surprised

when the filmmaker informs them Highsmith once had a fling with her cousin.

Highsmith

made her name with Strangers on a Train, but Hitchcock is only mentioned

in passing. However, the novel Carol (a.k.a. The Price of Salt)

is discussed at length, because of its lesbian themes. There is a bit of

discussion of Tom Ripley, her signature anti-hero, but a great deal of that

centers on the fourth book, The Boy Who Followed Ripley, because it was

partially shaped by one of her own romantic relationships.

Loving

Highsmith will

make viewers miss the Formalist school of literary criticism, which held it did

not matter who or what an author might be. The only valid question was whether

the book was any good. Instead, it is clear Vitija is only documenting

Highsmith because of her sexuality. Her work is of secondary importance.

That

is a shame, because Highsmith is a hugely significant writer, who arguably

transcends genre. She has inspired filmmakers like Hitchcock, Claude Chabrol,

Claude Miller, Rene Clement, Wim Wenders, Todd Haynes, and even Sam Fuller (who

helmed an episode of the Chillers anthology, based on her short

stories). Indeed, the most interesting sequences are those in which Highsmith

explains her books are not really about crime or murder, but the feeling of

guilt, or the absence thereof.

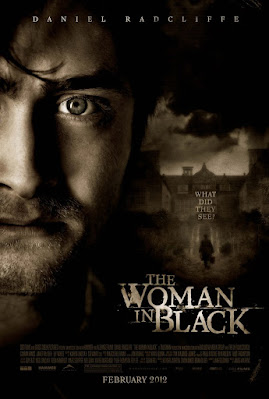

Arthur Kipps' assignment sounds like a nightmare from Hell: one solid week of

paperwork. He is supposed to organize the ratty old papers of the late Alice

Drabow, the former owner of Eel Marsh House. Frankly, the visitation of a vengeful

ghostly woman sounds like a welcome distraction from such drudgery, but

unfortunately, her appearances are a harbinger for yet another child dying in

the beleaguered local village. Despite the tragedies, poor Kipps still has to

get all those blasted papers in order in James Watkins’ Hammer-produced The

Woman in Black, which airs Thursday on Comet.

Kipps’

beloved wife died in childbirth, leaving him to raise their son Joseph on his own.

The senior partner of his proper Edwardian firm says he is sympathetic to Kipps’

situation, which means he really isn’t. Regardless, Kipps must sort out the

Drabow estate if he is to have a future with the firm. Unfortunately, the local

solicitor has been decidedly uncooperative, so Kipps must go to Eel Marsh House

and process all the paperwork, so they can clear the title for the prospective

heirs.

Of

course, he receives a nasty welcome from all the locals, except the wealthy and

skeptical Sam Daily. Yet, he too lost his young son in an incident attributed

to the Woman in Black. According to legend, whenever she is seen, a child dies through

an act of self-destruction. As a result, Kipps only makes things worse for

himself in the village when he asks about the strange woman he has seen around the

Eel Marsh grounds. Children do indeed start dying, which is especially alarming

to him, since Joseph and his nanny are scheduled to visit over the weekend.

Woman

in Black is

an entertaining gothic throwback, which made it an altogether fitting

production for the relaunched Hammer Films. As well as channeling vintage

Hammer, Watkins also picked up a step or two from films like Bayona’s The Orphanage,

using the full frame to tease viewers with shadowy figures, half-seen from down

long hallways. Yet, the wonderfully lush and decaying set designs are pure

vintage Hammer. Plus, the isolation of Eel Marsh House, built atop a rise in

tidal basin that is inaccessible during high tide, lends the film additional

claustrophobic creepiness.

Since

Daniel Radcliffe now shuns J.K. Rowling as a heretic who should be burned at

the stake, this could be his new favorite film. It is the second screen

adaptation of Hill’s novel, following a 1989 BBC production, and the first to

spawn an original sequel. It is refreshingly atmospheric and suggestive, rather

than bluntly gory.

This team of superheroes certainly holds franchise possibilities. That would delight

the low-budget film company The Asylum, because the characters are based on the

gods of ancient civilizations and therefore fair game for their “mockbuster” coattail

riders, like for instance their recent Thor: God of Thunder (not “Love

and Thunder”). Thor is not one of the Godlings, or their allies, but they will

meet Brokkr, one of the dwarves who forged his legendary hammer. Unfortunately,

an evil Mesopotamian goddess is threatening the Godlings and the world they

protect in Luke C Jackson’s graphic novel Godlings and the Gates of Chaos,

which is now on-sale.

Milo

just thought he was a fun-loving teen, with a talent for magic tricks that was

sometimes actually magical. However, he is the mortal incarnation of the Greek

god Dionysus. Fortunately, his once and future colleagues with the Knights of

Horus found him when their enemies were about to assassinate him. Like it or

not, he is the newest member of the team, along with Diana (whom he vaguely

remembers as Artmeis), Ra (the Egyptian sun deity), and Chaac (the Mayan rain

deity).

However,

he won’t be the new guy for long. They soon recruit Tiamat, the Babylonian

goddess of destruction. Her latest physical form is still young and immature,

but she is extremely powerful. She is also a bit unstable, which is why the minions

of Irkalla, the Queen of the Mesopotamian underworld try to lure her to the

dark side. She has plans Tiamat could help advance.

The

concept of the Godlings is not radically original (basically Marvel’s Thor and

the Avengers crossed with Percy Jackson), but Luke C Jackson forgoes a lot of

the obvious usual suspects, for a broader selection of heroes. Instead of yet

another Hercules, he gives us Dionysus and Nemesis, who is currently estranged

from the Godlings, because they are not sufficiently retributive for her tastes.

Jackson does not slavishly mold the young heroes’ personalities to match their

ancient personas, but he generally captures the broad strokes of their powers

and iconic traits. That might be a plus, especially if Godlings inspires

some young readers to take a deep dive into ancient history and religions.

The art credited to

Caravan Studio is energetic and the action scenes are easy to follow. It is

colorful and accessible for the younger demographic, but the wealth of

historical sources will intrigue some older superhero fans, as well. Again, the

Godlings are hardly unprecedented, but they are solidly executed for what they

are. Recommended for young superhero readers looking for something a little

different from the big two corporate universes, Godlings and the Gates of

Chaos is now available from Magnetic Force.

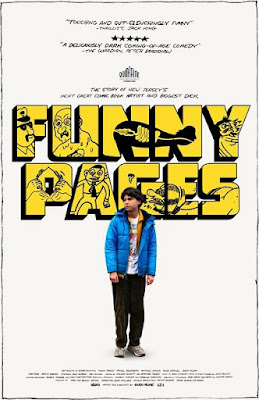

If you are an anti-social misanthrope who enjoys laughing at other people’s

freakish misfortunes, you are probably a consumer of underground comix, from

the likes of R. Crumb. Nobody is forcing you. Of course, most fans like young

Robert are convinced there are great truths in those baroquely gross pages. He

has a talent for drawing comics like his idols, but not for healthy human

relationships, as we see in painful detail throughout Owen Kline’s

wince-inducing Funny Pages, which opens today in New York.

Mr.

Kitano, Robert’s high school art teacher, always got him. Unfortunately, he is

killed in a freak accident, after an awkward nude modeling incident with his

student. You can tell right from the start this film will spare us nothing.

In

defiance of his conventional parents, Robert announces he will pass on college,

to pursue a career in comics. He will not be living under their roof either, to

prevent them from playing that parental card. Since his only income comes from

part-time work at the comic book store, Robert takes a shared room in an

illegal basement apartment in Trenton, with two old perverts. What he really

needs is a mentor and thinks he might have found one in Wallace, a former

color-separator from Image Comics. Unfortunately, Wallace is an on-spectrum

neurotic with impulse control issues that border on psychosis.

Funny

Pages is

unpleasant, but that certainly makes it true to the spirit of the underground

comix that partially inspired it. Kline and his cast make Ghost World look

innocent and uplifting. As result, the film hardly feels like any sort of love

letter to comics—more like an indictment.

Daniel

Zolghari is relentlessly abrasive and charmless as Robert. That means the young

thesp takes direction well, but that doesn’t make his performance any easier to

watch. Matthew Maher is also spectacularly ticky and creepy as Wallace, which

is definitely something.

As a scholar of myth and folklore, Alithea Binnie is familiar with the Twilight

Zone episode “The Man in the Bottle,” or similar such tales. She expects

the magical granting of wishes to necessarily result in ironic unintended

consequences. Yet, the djinn offering her wishes has a good point when he

argues she has free will, doesn’t she, so why should she be bound by the fate

of others? However, when he tells her his story, he gives her plenty of

examples of things not to wish for in George Miller’s Three Thousand Years

of Longing, which opens tomorrow in theaters.

Binnie

is used to academic conferences, but there has been something a little off

about this gathering in Istanbul. It must be fate, or something, that soon

guides her to pick up an old but supposedly valueless bottle in a bazaar. Guess

what’s inside. Yes, Idris Elba. The djinn only needs a little time to adjust to

Binnie’s language of choice and her physical scale. Then he must grant her

three wishes, or suffer a terrible fate.

Naturally,

Binnie asks how he got in that bottle in the first place. It is quite an epic

story, spanning thousands of years and featuring a cast of characters including

the likes the Queen of Sheba, King Solomon, and various royal despots from

Byzantine antiquity. Ironically, his tragic history rather reinforces Binnie’s

skepticism regarding wishes, but it also fascinates the Joseph Campbell-ish

scholar.

Admittedly,

Miller has a little trouble wrapping up TTYL (even though it was adapted

from the A.S. Byatt short story “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye"), but his

patience and deft touch has produced a terrific film, loaded with rich visuals

and exotic settings. Somehow, Miller managed to evoke Thief of Baghdad vibes

in a way that should not arouse the professionally offended.

Idris

is about the only thesp who could play the Djinn with the appropriately

imposing physicality and dry wit, while still evoking the sense of an old soul

within. He also generates a lot of heat on screen with Aamito Lagum, as the

Queen of Sheba.

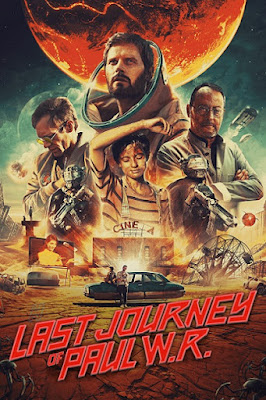

Sometimes you wake up and just don’t feel like saving the world. That is basically

what happened to Paul W.R. The problem is, he is scheduled to do exactly that.

Only he has the sufficient skills to save Earth from a collision with the Red

Moon in Romain Quirot’s Last Journey of Paul W.R., which releases

tomorrow in theaters and on-demand.

One

day, the Red Moon just appeared in the sky, big and ominous looking, but Paul

W.R.’s father Henri recognized it as a source of cheap energy. Unfortunately,

the celestial satellite did not take kindly to being exploited, or at least

that was Paul’s theory. Regardless, the Red Moon shifted into a collision

course with Earth and only Paul W.R. can navigate through its magnetic field to

deliver the explosive charges. Of course, this would be a suicide mission, but

the grateful world has hailed W.R. as its hero and savior.

A

slight complication developed when Paul W.R. disappeared days before doomsday. Dystopian

France’s jackbooted police and surveillance system are on the lookout for him,

but there are a lot of options for hiding out in the wasteland. What does he

want? Maybe he isn’t sure himself.

Paul

W.R. won’t tell us either, because unlike the short film Last Journey of the

Enigmatic Paul W.R., the title character never breaks the fourth wall this

time. He also no longer has the omniscient power to read minds, whether he

wants to or not, so apparently, he really is a lot less “enigmatic.”

Indeed,

Quirot made considerable changes in expanding Paul W.R.’s story to feature

length. Unfortunately, most of them water-down and undermine the poetic poignancy

of the original short. After screening at the 2016 Tribeca Film Festival, it is

now available online here. It is highly recommended, but maybe viewers ought to

just stop there.

One

thing the feature has going for it that the short didn’t is Jean Reno, who plays

Paul’s scientist-industrialist father, with his usual gravitas. This time

around, Paul’s brother Eliott is the one that can read minds, but he picked up

the uncanny talent after he failed to fulfill Paul’s mission. Unfortunately, he

came back changed.

Milos Havel's Barrandov Studios made some great films and some unfortunate propaganda, during both the German and Soviet occupations. However, that leads to some intriguing drama in the Czech series PRIVATE LIVES (airing on EuroChannel and streaming on Freeve). EPOCH TIMES review up here.

You might think it would be easier to fight off hostile aliens in the year

2022 than back in the Fourteenth Century Goryeo Korea, but Earthlings would be

technologically outclassed in either era. At least back then they had magic and

superheroes. In addition to all of the above, this film also has time travel,

so it pretty much has it all. However, it will not necessarily be clear which

alien from the future is inhabiting which human character from the past in director-screenwriter

Choi Dong Hoon’s wildly inventive Alienoid, which opens Friday in New

York.

630

years ago, the Earth’s resident prison warden, simply known as “Guard” and Thunder,

his AI assistant, drove their SUV into Goryeo times to recapture a fugitive

alien. Guard represents a galactic order that imprisons the consciousnesses of

their criminals inside the brains of humans on Earth. In most cases, both the

host and the imprisoned remain unaware of the situation. However, when the

aliens are awakened, they can take control and run amok. In this case, their

fugitive sought to escape into the past. Guard and Thunder nabbed their quarry,

but the collateral damage left infant Ean an orphan.

Stone

cold Guard was willing to abandon her to fate, but the stealthy Thunder smuggled

her back to 2022 for Guard to raise as his daughter. He is not an affectionate

father, but parenthood helps establish his human cover. However, Ean is smart

for her age, so she suspects Guard is involved in something weird.

Meanwhile,

six centuries earlier, Murak, a clumsy, but sometimes powerful Taoist dosa

magician is on a quest to find a legendary blade. Initially, he finds himself

competing against the mysterious “Girl Who Shoots Thunder,” who wields some

very contemporary firearms, but the real threat comes from a cabal of alien

body-snatchers.

Alienoid

is

a crazy kitchen sink movie, filled to the rim with every possible science

fiction and fantasy element imaginable. Yet, it is also highly refreshing,

because it creates a whole new science fiction universe that is not tied into

and carrying the baggage of the Marvel or DC Universes. Hollywood just doesn’t

have this kind of originality or ambition anymore. Is this really the safest or

most cost-efficient way of imprisoning criminals? Probably not, but it

certainly provides the impetus for a lot of crazy and thoroughly entertaining

mayhem.

David Locke wanted to see justice done by the International Criminal Tribunal

for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), but not so surprisingly, he finds the

UN-chartered organization is stymied by politics (imagine that). It is personal

for him, because a Serbian war criminal killed the woman he loved. When he gets

a lead on her killer, the ICTY is too busy winding down its mission and patting

itself on the back, so he goes it alone in director-screenwriter Alastair

Newton Brown’s Here Be Dragons, which screens during this year’s

Cinequest Film & VR Festival.

While

stationed as a UN “Peace-keeper” during the Yugoslav Wars, Locke came face to

face with Ivan Novak, just when he was dumping the bodies of his girlfriend’s

village. Yet, he was ordered to stand down, because his unit was insufficiently

armed and was only authorized to conduct a prisoner exchange. As the top

investigator for the ICTY, he believed Novak had been killed. However, just as

the ICTY announces its dissolution, Locke is approached by his girlfriend’s

brother, Emir Ibrahimovic, the only survivor of the massacre.

Now

a wealthy Swedish industrialist, Ibrahimovic has information regarding Novak’s

whereabouts. It turns out, he is living openly under an assumed name in

Belgrade. To add insult to injury, he currently runs PTSD and reconciliation workshops

for survivors of the civil war.

HBD

is

directly rooted in the events of the early 1990s and 2017, but in terms of tone,

it is very much akin to some of the anti-hero thrillers of the 1970s. Brown

seems to have a bit of a man-crush of the lead actor (and producer) Nathan Clark Sapsford stalking through the dark streets of Belgrade in his half-overcoat,

but to be fair, he is pretty cool looking.

Sapsford

doesn’t merely brood. He plays Locke so tightly-wound, he could snap at any

moment. Yet, he is not an empty existential protag. Throughout it all, Brown

makes it clear the man always holds to some notion of justice. In contrast,

Slobodan Bestic’s Novak is a surprisingly subtle and challenging figure, who tries

to literally embody the notion that healing comes through the passage of time,

rather than cathartic retribution. That is literally what his counseling

argues.

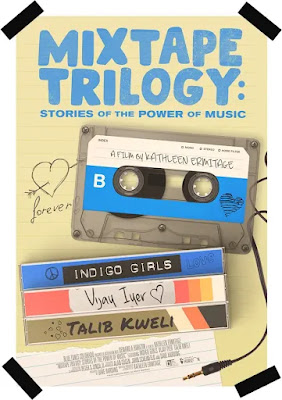

Even the biggest names in jazz often play intimate clubs, so jazz fans have

an unusually good chance of interacting with their favorites. If you go to

up-and-coming musicians’ gigs, you might just make a friend. Some of my

favorite musicians are even in-real-life friends with my entire family. It is

nice to know this can also happen in other musical genres. To illustrate the point,

documentarian Kathleen Ermitage examines the close relationships the Indigo Girls,

jazz pianist Vijay Iyer, and rapper Talib Kweli have with special select fans

in Mixtape Trilogy: Stories of the Power of Music, which screens during

this year’s Cinequest Film & VR Festival.

Sadly,

this film could never screen in China, under the current CCP regime. For one

thing, Indigo Girls super-fan Dylan Yellowlees identifies the Tiananmen Square

Massacre as one of the defining incidents of her late-1980s youth. That would

be simple enough to edit out, but the state censors still would never approve Yellowlees’

open and frank discussion of her coming-out-experience, which largely

overlapped with that of the band’s. Understandably, it was easy for her to identify

with them and she found great meaning in their lyrics. When Yellowlees finally

met them while working as a programmer for a local theater, they got on like a

house on fire.

Likewise,

Iyer found something of a kindred spirit in Garnette Cadogan, a restless

academic with adventurous taste in music. Arguably, this is the most personal

segment of the film, since their relationship appears to be the closest.

Indeed, Iyer often describes Cadogan as a member of his family. Sometimes, Iyer

can be counter-productively didactic, but the greatest controversy he and

Cadogan address in the film is the criticism the pianist does not sufficiently

swing. That is the sort of tired debate that hurts jazz rather than defending

it, so Cadogan was right to call it out. (Indeed, Iyer’s Radha, Radha is

a rich and rewarding composition.)

You can tell from imdb the cast of Eli Roth’s Cannibal Holocaust-inspired

film appeared in many subsequent projects, some even soon after its release.

Nobody died during the shoot and Roth never implied that they did, nor did he

depict any animal killings on-screen, real or simulated. Yet, viewers cannot

miss the spirit of old school Italian cannibal exploitation movies in Roth’s The

Green Inferno, which screens at MoMA, as part of its Messaging the Monstrous: Eco Horror film series, in recognition of its status as a true work of

modern cinematic art.

Initially,

Justine admires the commitment and idealism of Alejandro’s campus “social

justice” organization, but her roommate Kaycee recognizes his charisma as the persuasive

snake oil of a cult leader. Nevertheless, Justine agrees to participate in

their upcoming “action,” in which they will live-stream themselves blocking

bulldozers poised to clear-cut a portion of the Peruvian Amazonian rainforest.

However, she is bitterly disillusioned when Alejandro puts her life at risk, to

capitalize on her father’s position as a UN attorney. Things get worse on the

return trip, when their plane crashes in the middle of hostile indigenous

territory.

Justine

survives with a handful of activists, awkwardly including Alejandro. His

behavior is a bit troubling, especially when he discourages and even actively

hinders escape attempts. It turns out he is a truly hypocritical scumbag—and one

of the most detestable, but distinctly notable movie villains of the

late-twenty-teens.

As

in Deodato’s cult-favorite, a group of privileged Americans (who would traditionally

be profiled as woke hipsters) go to the Amazon and make everything worse. There

might be an environmental message to Green Inferno (don’t raze the rainforest,

because it will have dangerous consequences), but it is the depiction of the

professional activist-class is what really defines the film, because it cuts so

close to the bone. Roth’s screenplay, written with Guillermo Amoedo made a lot

of critics uncomfortable, because there was a lot of truth to it.

Plus, it addresses the practice of Female Genital Mutilation, in ways that

highlight the horror of the practice and undercut cultural relativism. Frankly,

anyone requiring “trigger warnings” should skip this film. It was intended for

grown-ups.

These game designers and gamers aren’t like the characters of One Second After.

Their digitally-dependent lives make them particularly unprepared for the

destruction wrought by an electromagnetic pulse (EMP). However, they think they

unique insight that will help them overcome, because the disaster appears to be

unfolding just like their scenario of the horror-survival game they wrote and

play. Regardless, they must somehow fight their way out of the building in the

six-episode Pulse, which is now streaming on BET+.

The

game of Pulse is personal to Jaz, Caspar, and Errol. They designed it

together and modeled the playable characters after themselves. After selling

out to a big company, they reluctantly made many compromises when designing the

new reboot. Jaz is tired of hearing criticism from Eddie, the building’s

toxic-fan security guard, especially since she largely agrees with him.

Unfortunately,

they all must take Eddie’s notes seriously when an apparent EMP fries all the building’s

electronics. Rather perversely, Eddie starts conducting a deadly Pulse game

in real life, tauntingly challenging Jaz and her colleagues to survive each

deadly level of the building. Originally designed for the state secret service,

the blocky brutalist behemoth has some seriously evil feng shui. It was a scary

place, even before all its occupants started going stark raving mad. First the

EMP started scrambling the electrical charges in everyone’s brains. Then a

carbon monoxide leak drove them into full-blown psychosis.

The

Pulse office was spared the worst effects of the chemicals, but the EMP really

did a number on Jaz. She was already diagnosed with Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS),

but its effects have been intensified by the electric charge. Ironically, in

the game, her character’s AIWS gives her an advantage to see beyond the

deceptions of ostensive reality, which also might now be the case for Jaz in

real life too.

Admittedly,

Pulse has issues with logic, but it was clearly made by and for survival

horror video game players. Everyone who was disappointed in Netflix’s utterly

dreadful Resident Evil reboot (probably the worst series of the year),

should watch Pulse instead. It is a high energy, often bloody

celebration of mayhem, which also features some absolutely crazy, but weirdly

satisfying twists. Most of what fans want from Resident Evil they can

find here.

You will learn more watching a few hours of the Food Network than from

attending this casual Italian restaurant chain’s special managers’ training

workshop, but it has the distinct advantage of being in Italy. That definitely

interests Amber, who has never been out of Bakersfield. She hopes to find

romance in Italy, but stumbles across trouble in Jeff Baena’s Spin Me Round,

which opens today in New York.

Initially,

it seems like there is a bit of a bait-and-switch going on with the managerial

seminar. They were supposed to stay in founder Nick Martucci’s villa, but

instead they are stuck in a strip mall budget inn. However, when Amber catches

Martucci’s eye, he tries to whisk her off her feet. His loyal assistant Kat

facilitates his courtship, but she also shows an interest in Amber as well.

Much

to Amber’s surprise, all the attention ends just as suddenly as it began. Martucci

appears to be romancing other women in the program, while Kat mysteriously

disappears. She starts to suspect it is all some sort of sleazy grooming

operation, especially when her colleague Dana reveals he and his fellow manager

Fran are two of the only men to ever participate in the program. They also both

happen to have names commonly associated with women.

Spin

has

a reasonably promising premise, but it was not sufficiently developed. Frankly,

it only really gets funny when Amber and Dana team-up to sleuth out the truth behind

their seminar. Alison Brie and Zach Woods bounce off each other nicely in these

sequences. However, most of the first half of the film just tries to force

laughs out of uncomfortable situations. It does not help that Spin features

several thesps whom the dictation-taking entertainment press keeps trying to

convince us are funny, but they really aren’t, such as Fred Armisen and Molly

Shannon. True to form, they just sap the energy out of Spin.

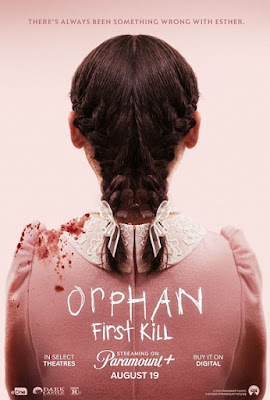

This entire film is a spoiler alert for its possible franchise, because if

you haven’t already seen Jaume Collet-Serra’s Orphan (released in 2009),

it reveals the original film’s big shocking twist in the first ten minutes. There

is a very good reason nasty little Leena has been confined to an Estonian

asylum for the criminally insane. Viewers know her better as Esther, the name

she adopts after her violent escape in William Brent Bell’s Orphan: First Kill,

which releases today in theaters and on-demand.

Dr.

Novotny kept warning his staff to always be on their guard when around the

little monster, but they just didn’t listen. A few bloody murders later, Leena

finds a photo online of Esther Albright, a missing American girl she can pass

herself off as, due to the passage of time and a bogus Russian kidnapping yarn.

Of course, Albright’s sensitive artist father Allen is so overcome with joy, he

unquestioningly accepts everything she says. However, Tricia Albright knows there

is something wrong with her story and their child psychologist also notices

some inconsistencies.

Make

no mistake, Mother Albright is one tough customer. People are always so dumb in

horror movies, but not her, no siree. Esther is a master manipulator, but she

will have a harder time pulling-off her Bad Seed-esque head-games with Ms.

Albright than she did with Vera Farmiga in the first film. In fact, their cat-and-mouse

business is what makes First Kill so much fun.

It

is pretty amazing Isabelle Fuhrman can still play Esther, over ten years after

the first film released. Admittedly, she had some SFX help, but there is also

something about the character’s sinister nature that encourages the suspension of

disbelief in this respect. Yet, Julia Stiles’s performance as Albright is what

really makes the film work so well. She is sharp and witheringly funny. As a

result, she and Esther are pretty evenly matched, which actually builds the

kind of tension and suspense that is hard to get from prequels (because let’s

face it, logic already tells us exactly what will happen).

Peacock's Undeclared War has some so-so personal melodrama, but its realistic depiction of Russian cyberwarfare and toxic propaganda makes it required viewing. Epoch Times exclusive review up here.

It is weirdly fun to compare and contrast this film with Noel Marshall’s

infamous Roar. In that film, Tipi Hedren’s actual family pretended not

to be scared-to-death of the very real lions, rough-housing around them. In this

new film, Idris Elba’s fake family make-believes they are absolutely terrified

of the CGI lion stalking them. The production of the latter was obviously much

more responsible. The law of the jungle still remains harsh and unforgiving in

Baltasar Kormakur’s Beast, which opens this Friday.

Dr.

Nate Samuels’ family is going through a rough patch. After he and his wife

separated, she soon was diagnosed with cancer and quickly succumbed. For his

daughters, Mere and Norah, it was definitely a case of “bad optics.” To heal

their family unit, Samuels brought them back to his wife’s ancestral home in

Africa, where the couple’s mutual friend, Martin Battles works as a wildlife

ranger (and possibly an underground anti-poaching activist).

Battles

thought he would take them out on a nice photo-safari. Instead, they stumble

across a village that had been decimated by a rogue lion. That would be the big

one that escaped the poaching gang during the prologue. Uncharacteristically,

he keeps ripping and gnashing his prey, without stopping to feed, because he is

mean-mad with mankind, so when he sees the Samuels’ range rover, he starts

hunting them too.

Beast

certainly

has an environmental message, but it is a worthy, focused point. Tragically,

there has been a surge in lion poaching, to meet the demand for increasingly

rare tiger bones, which are used as an unfounded remedy for impotence in regional folk “medicine.” This is an illegal trade China (supposedly Africa’s best

friend) could surely curtail, but the CCP isn’t doing that at all. Maybe the

big cat should pay them a visit.

Regardless,

there is no question the big guy is the star of Beast and the CGI

animating him looks surprisingly lifelike. Its movements are convincingly realistic

and his behavior is suitably ferocious to create tension and suspense. However,

the film never really instills any “personality” in him, beyond a

vengeance-hungry killing machine.

This film makes “sparing a square” look like not such a big favor after all—not

that there is any toilet paper in this disgusting rest-stop bathroom. Hungover

Wes isn’t making it any cleaner, either, but his neighbor in the adjoining

stall will really make things messy in Rebekah McKendry’s Glorious,

which premieres tomorrow on Shudder.

Wes

was on the road, missing his ex, Brenda, but she wasn’t taking his calls. In

retrospect, it was probably a mistake to get blind, stinking drunk at the lonely

rest-stop and then burn his pants in a bonfire, but it apparently seemed like

the thing to do at the time. As a result, he is in pretty bad shape when the

voice of Farmers Insurance starts talking to him from the stall next door. There

happens to be a hole in the wall, but it cautions him not to look, claiming its

appearance would drive Wes mad.

The

voice Wes will call Ghat claims to be something truly Lovecraftian and it

certainly seems to have that kind of supernatural powers. Forr one thing, Ghat

can get inside of Wes’s head, interrupting the memories he tries to retreat

into. It wants something from Wes, and only Wes. Nobody else is invited to Ghat’s

party.

Glorious

is

often pretty gross, but also pretty clever. McKendry deftly exploits the claustrophobia

of the setting and its inherent ickiness. What really makes the film though is

J.K. Simmons, whose voice is absolutely perfect for the commanding, yet weirdly

ingratiating Ghat. This is probably the best voiceover performance of the year,

even including most animated films.

Ryan

Kwanten is similarly well-cast as the depressed and degenerate Wes. Just

looking at him makes you want to take an Alka Seltzer. He also presumably

carried on a pretty intense one-sided conversation, given Ghat’s crazy talk

must have been recorded separately. Professionals do that all the time, but he

had to reach some manic extremes.

Ironically, a crime spree can give a sense of urgency and momentum to life.

Initially, Val and Kevin figured they had nothing to lose, except their lives,

which they were tired of, so why not end it all by going a little outlaw?

Perhaps a fresh perspective will change their minds, or perhaps not in Jerrod

Carmichael’s On the Count of Three, premiering tomorrow on Hulu.

Kevin

has been miserable all his life, for many reasons, starting with Dr. Brenner,

who molested him when he was a young boy. Val isn’t much happier, but he doesn’t

have as many excuses. Nevertheless, he wants to end it all too, so he springs

his friend from the psychiatric hospital, where he was committed after his

recent suicide attempt. Val wants them to do the job right, by simultaneously

shooting each other in the head. Kevin is not against it, but he wants to

celebrate their last day together first, possibly by settling some scores. Dr.

Brenner is at the top of his list, but Val might also want to visit the father

who did him wrong.

At

this point, the film and all its promotional materials are covered with trigger

warnings and referrals for counseling help. That is all well intentioned and

maybe a little of it is helpful, but society managed to survive Hal Ashby’s Harold

and Maude and Burt Reynolds’ The End. We should be able to weather

this film as well. Frankly, a little dark humor can be cathartic and healing.

There

is some here (especially when it skewers Kevin’s kneejerk woke, anti-gun rights

politics), but screenwriters Ari Katcher and Ryan Welch really should have

cranked up the mordant attitude much higher. Too often, they focus on the sad

and tragic (which are usually less therapeutic). However, Lavell Crawford and

Tiffany Haddish both deliver some sharply cutting lines. The support work in Count

is first-rate, including Henry Winkler, who will shock and even scar those

who grew up with him on Happy Days, with his coldly manipulative

performance as Dr. Brenner.

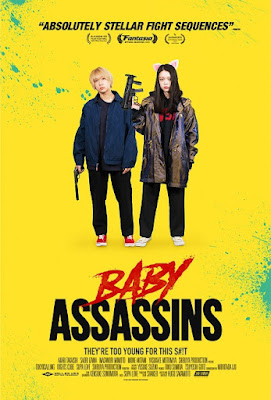

Sometimes, on-the-job training is better career prep than advanced course work.

Murder-for-hire colud be one of those vocations. It seems to suit Chisato

Sugimoto and Mahiro Fukagawa, despite their conflicting Odd Couple personalities.

They are compatible professionally, but their employer also insists they room

together in Yugo (Hugo) Sakamoto’s high body-count comedy Baby Assassins,

which releases today on VOD.

Sugimoto

is cute and bubbly, whereas Fukigawa is a withdrawn self-avowed sociopath.

Together, they have a knack for killing, but holding down their

company-mandated part-time cover jobs is a different story, especially for Fukigawa.

Unfortunately, their latest target was Yakuza-connected, which displeases the

boss, Ippei Hamaoka. Only he should be able to kill his people. As part of his

female-centric makeover of his gang, Hamaoka instructs his daughter Himari to

find and eliminate the killers.

Eventually,

matters escalate into a full-blown war between the Yakuza and the two clueless

high school grads. However, it is more likely the two roommates will kill each

other before Hamaoka’s enforcers can get their act together. This is a comedy,

but Sakamoto is not fooling around when it comes to the action. There are some

brutal, no-holds-barred fight scenes and plenty of headshot-style executions.

It almost feels like a Miike film, but it is lighter, leaner, and more

down-to-business focused.

Josephine Baker was not always topless when she performed in the iconic banana

skirt, so it really isn’t cheating to depict in some sort of bikini top. Be

honest, when you see a graphic novel biography of Baker for ages 7-10, isn’t

your first question how they depict her vintage Parisian costumes (or lack

thereof)? Parents who are fans can certainly supplement as they see fit, but

those who are also concerned about the premature sexualization of their

children shouldn’t object to anything in Lauren Gamble’s It’s Her Story: Josephine

Baker, illustrated by Markia Jenai, which goes on-sale today.

Gamble

does indeed follow the chronological facts of Baker’s life, including her

triumph in Paris, her clandestine service with the French resistance during the

German occupation, and her support of the American Civil Rights movement. Someone

should really write a separate book about her work as a spy, because it is such

an intriguing historical episode, but at a kid-friendly 48 pages, Gamble’s bio

does not have the time or space to get sidetracked.

The

only real problem is the clunky dialogue, which unnecessarily echoes the

sentiments of the descriptive captions. They are mostly declarative or condemning

statements that do little to humanize Baker. Young kids are smart, they can

handle a little humor and nuance.

Regardless,

Jenai’s art is colorful and vibrant, capturing the elegance and extravagance of

Baker’s stage career. Some panels would make great posters, if the dialogue

balloons were stripped out. It is also nice to see them drop Ethel Waters’ name—we

can always hope the young readers will look her up too.

Harry Orwell had a cool name, but the title of his series didn’t use the best

part. He was also a little older and a lot more broken down than most TV

detectives of his era, but that made him a credible jazz fan. His taste puts

him in the right jazz club, at the right time, to help a legendary trumpeter in

the “Sound of Trumpets” episode of Harry O, directed by John Newland (the

host and director of One Step Beyond), which airs late night

Saturday, as part of Decade TV’s weekend binge.

Art

Sully (born Arthur Daniels) played with the greats, but it has been a while. He

was just paroled after serving more than ten years for a dubious murder charge.

He happens to crash Ziggy’s set at Orwell’s favorite Santa Monica jazz club and

then crashes at Orwell’s pad. When he comes to, he “borrows” the MG that spent

the better part of the series in the repair shop (MGs were like that). Despite

his annoyance, the thugs that come looking for Sully convince Orwell to help

the musician. He is also moved by the concern of Chuck Henry, another jazz legend,

and Sully’s daughter, Ruthie Daniels, an up-and-coming vocalist.

By

this time, the setting of Harry O had already moved from San Diego to

LA/Santa Monica, which meant all the time Orwell spent on the bus was

particularly sad. The shift probably paid off, since Anthony Zerbe won an Emmy

playing Orwell’s reluctant police contact, Lt. K.C. Trench. Based on this

episode, Zerbe and star David Janssen had an amusing bickering-bantering rhythm going

on. Of course, LA was also a more logical setting for a jazz story.

Although

the specific musicians are not credited, this episode was scored by the preeminent

bop trombonist J.J. Johnson, who knew everybody. For this episode, he used a

lot of percussion motifs. Among the guest stars, Cab Calloway was of equal or

possibly even greater stature, playing the decent and dignified Henry (an

Ellington-esque figure), with his showman-like charm.

Brenda

Sykes, who played Ruthie Daniels, also had important jazz connections, as the wife

of vocalist Gil Scott-Heron. Frankly, it is a shame she did not record more,

because she performs a nice jazzy rendition of “What is this Thing Called Love”

and a more R&B-ish (but maybe even more distinctive) version of “Never My

Love.” Plus, there is a one-armed former trumpeter turned pawnbroker, who must

have been inspired by Wingy Manone.

Da Vinci is one of the major reasons why we have the term “Renaissance man,”

because he was one of the originals (and one of the most important). Yet, he

hardly ever finished anything. At least that is the impression viewers get from

his latest episodic series treatment. Creators Frank Spotnitz & Steve Thompson

focus more on the intrigue, scandal, and ambiguous sexual orientation, which is

surely why it was acquired by the CW, where it premieres tomorrow.

Leonardo

Da Vinci is keenly aware of his illegitimacy and the sense of abandonment he

carries all his life. Nonetheless, his middle-class notary father helped him

attain an apprenticeship under Andrea del Verrochio. Not surprisingly, the

student’s promise soon shows the potential to eclipse the master. Da Vinci’s

work even attracts an offer of patronage from Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of

Milan, whom Da Vinci rashly turns down, out of loyalty to Verrochio.

During

his apprentice years, Da Vinci also forges an unusual relationship with Caterina

de Cremona, a lowly servant, with ambitions many would consider well beyond her

station. They do not exactly sleep together, because Spotnitz and Thompson

clearly suggest that just isn’t Da Vinci’s thing. However, they still have a

deeply felt, but highly tumultuous relationship. In fact, as the series opens,

Da Vinci stands accused of her murder by Stefano Giraldi of the Milan constabulary.

The truth will be revealed in flashbacks, prompted by his interrogations.

Admittedly,

Da Vinci’s body of work is frustratingly limited compared to many of his

contemporaries, but Leonardo often makes him look like a serial

procrastinator. Dan Brown fans will also be annoyed Spotnitz and Thompson never

show him incorporating any Fibonacci sequences into his masterworks. The new

series at least halfway accurately chronicles the major events of the Da Vinci

historical record, especially compared to David Goyer’s Da Vinci’s Demons.

However, the way the latter portrayed Leonardo as a carousing degenerate was

much more entertaining than the humorless angst of Aidan Turner (from the new Poldark)

this time around.

Nonetheless,

Turner generates more than enough brooding and sexual confusion to keep the

melodrama chugging along. Eventually, he and Matilda De Angelis (playing de

Cremona) develop some intriguing chemistry together. Of course, James D’Arcy is

reliably arrogant as the villainous Ludovico. The real problem is Freddy

Highmore is badly miscast as the intrepid Giraldi. The part needed someone like

Tim Roth, who can play it convincingly sly and cynical, before rediscovering

his idealism, thanks to Da Vinci’s art. Highmore just wasn’t up to it, but he

was an executive producer, so he was a fact of life.

This particular virus really was fake news. That is why it was so heroic and ingenious.

After the German occupation of Rome in 1943, until its Allied liberation, a

handful of doctors and supporting staff maintained the secret “K” ward, where

they sheltered Jews, who were supposedly suffering from a completely fictitious

virus. Documentarian and film score composer Stephen Edwards chronicles their courageous

efforts in Syndrome K, which releases tomorrow on VOD.

Fatebenefratelli

Hospital was Catholic by affiliation and ownership title. Yet, the Jewish Dr.

Vittorio Sacradoti made a professional home there before the Germans invaded

and a literal home during the occupation. He also found sympathetic colleagues

in the senior physician, Dr. Giovani Borromeo and Dr. Adriano Ossicini, who was

already active in the anti-Fascist underground. Together, they devised the Syndrome

K deception, as a means to shelter Jewish Italians, shrewdly exploiting the

National Socialists’ phobic obsessions with disease and impurity.

They

also harbored resistance figures on a short-term basis and provided communications

support to the underground. Since they were literally owned by the Church, it

is highly likely Pope Pious XII was aware to some extent of their activities,

which he apparently approved, at least passively.

In

fact, Edwards devotes a good deal of time to analyzing the controversial Pope’s

actions in response to Hitler and the Holocaust. Rather than attacking or

defending, Edwards and his on-camera experts are surprisingly evenhanded. While

the Pope still gets mixed-to-negative marks, the rank-and-file priests and nuns

who sheltered Roman Jewry throughout the city get their due credit. As a

result, this is a film that should really bring people together and inspire

good fellowship.

Claude Ridder is not your typical time-traveling hero, but he was a fitting

protagonist for Alain Resnais, the late surrealist filmmaker, who was often

associated with the French New Wave, despite never fully identifying with the

movement. In fact, Resnais’s take on time-travel film could represent the

ultimate Nouvelle Vague film, because of its radically fractured approach to

time. After consenting to serve as a human guinea pig in a time-traveling

experiment, Ridder finds himself uncontrollably reliving brief snippets of his

life in Resnais’s Je T’Aime, Je T’Aime (I Love You, I Love You),

which is definitely worth re-watching in honor of the filmmaker’s recent centennial.

Ridder

is a pitiable fellow in many ways. He still works as a shipping clerk at a

Parisian publishing house, due to his chronic lack of ambition. Ridder also

just survived a suicide attempt. Rather symbolically, he tried to shoot himself

through the heart. Yet, his rather cavalier attitude towards life is what

attracts the Crispel Research Center.

As

the various blandly bureaucratic scientists explain to Ridder, they

successfully sent mice back in time for one minute and then returned them

safely. Of course, mice cannot discuss the experience, so they wish to recruit

him to be their first human test subject. Ridder does not have any good reason

to decline, so he agrees.

Much

to everyone’s alarm, something goes wrong with the process this time. Ridder

keeps randomly “quantum leaping” into past episodes of his life, many of which

involve his troubled relationship with Catrine, who struggled with depression until

her early demise. At various times, Resnais leads the audience to suspect

something definitely transpired between them that contributed to her death and his

suicide attempt.

Resnais’s 1968 film is often considered a source of inspiration for Eternal

Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, but it is worth noting Je T’Aime, Je

T’Aime also predates Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five and

the subsequent George Roy Hill film adaptation. It certainly constitutes a

fractured narrative, by any standard or measure. As Ridder endures the shuffle-play

of his sad history for viewers to watch, each jump gets shorter, with surreal

imagery starting to intrude into what had appeared to be an otherwise mundane

existence.

Arguably,

Resnais’s narrative approach was considerably ahead of the other genre films of

its era. However, the scenes in the Crispel Center have a cold, sterile vibe

reminiscent of classic 1960s science fiction films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville

and Dr. Heywood Broun’s early sequences in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

That coldness is similarly reflected in the characters, especially Ridder, who

is standoffish and often rather self-sabotaging. Likewise, Catrine is usually

moody and distant—or at least that is how he remembers her.

Resnais

demands the audience’s full attention, by revisiting key incidents from

different perspectives, at slightly earlier or later time-frames. It might look

repetitive, but there are nuances to pick up on. Ultimately, when it all comes

together, it lands with devastating emotional force.