Hong Sang-soo’s films do not usually

bring to mind the career of American actor Neal McDonough (seen in films like 1922

and the series Yellowstone), but one of his latest characters also happens

to be an actor who refused to perform in love scenes. While McDonough admirably

takes his commitment to his wife seriously, Young-ho maybe got ahead of himself

with his girlfriend Ju-won. Of course, communication is awkwardly imperfect for

everyone in Hong’s Introduction, which screens during MoMI’s Curator’s Choice series.

At a mere sixty-six minutes, Introduction has

the virtue of being Hong’s shortest film released this year—out of a whopping

total of three. It also happens to be improvement over The Novelist’s Film.

It still lacks the playfulness of his best films, but the cagey temporal jumps

harken back to the old Hong. He also rather deviously has his characters

withhold information until late in their conversations, to keep viewers

somewhat in the dark.

In the first part, we see Young-ho cooling his

heels in his semi-estranged doctor-father’s waiting room, hoping to ask for

money to allow him to study abroad. Part 2 is a flashback, wherein he visits

his (future ex-) girlfriend in Berlin, where she is studying fashion. Hong

flashforwards again in Part 3, revealing his relationship did not last, despite

his self-defeating on-screen abstinence.

Dionne Warwick almost sang a Bond theme,

but “Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” was replaced by Tom Jones’ “Thunderball” at the

last minute, because the producers were so literal-minded. Nobody mentions it

in her documentary, probably because she had 56 other singles that hit the

charts, making her one of the top-selling recording artists of all time.

Warwick looks back on her life and career in David Heilbroner & Dave Wooley’s

Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over, which airs Sunday night on CNN.

Warwick is widely considered the first vocalist

to fully crossover from R&B to pop. Her long association with the

song-writing duo Burt Bacharach and Hal David is the major reason why. They

have been dismissed as loungey, but tunes like “Alfie,” “I’ll Never Fall in

Love Again,” “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” and “Always Something There to

Remind Me” are quite interesting musically. If nothing else, Heilbroner and

Wooley will convince viewers the time has come for an in-depth documentary

profile of Bacharach.

Jazz fans will also be interested to know

Warwick was twice married to jazz musician William Elliott, who was a sideman

with Willis “Gator” Jackson and co-led a session with Joe Thomas. Their first

marriage was sort of a false start, but the second take lasted twelve years—and

Warwick’s memories of it sound mostly positive. It was with Elliott that

Warwick had her two sons, Damon and Elliott, who are far and away the doc’s

funniest interview subjects.

Everyone reaches a point where they

decide they have to start acting like grown-ups and accept responsibility. For most people, that is the

time when they start showing up to work on-time and paying their bills. Maxine

Ann Carr faced this crossroads when the police started suspecting her fiancée,

Ian Huntley had abducted and murdered two ten-year-old girls in Soham. The vast

majority of the British public following the case would argue Carr arrived at

her turning earlier, when she knowingly provided Huntley a false alibi and

therefore bears some moral and legal culpability as an accomplice after the

fact. Writer Simon Tyrrell tries to maintain some ambiguity during the

three-part Maxine, which is probably why so many British viewers hated

it. Be that as it may, Maxine premieres for American audiences tomorrow

on BritBox.

The working-class Huntley somewhat swept Carr

off her feet, but he quickly showed his abusive and controlling true nature. Nevertheless,

Carr remained loyal to him, largely accepting his evasive excuses regarding his

past legal troubles. Somehow, he managed to get a caretaker

(janitorial/maintenance) position at a Soham school, because his background

check was never carried out, due to bureaucratic snafus. Carr also found

employment as a teacher’s assistant, since she had a clean record.

Jessica Chapman and Holly Wells were two of the

girls she helped teach, so maybe she really was as upset by the news of their

abduction as she presented to the world. She had been out-of-town when they

were abducted, but she agreed to pretend otherwise, thereby alibiing Huntley.

Initially, Tyrrell and director Laura Way lead us to suggest she genuinely

believed he was innocent, but legitimately concerned he would be scapegoated

because of his record. However, his dodgy behavior just gets progressively more

and more suspicious.

Neither the victims nor their grieving families

appear in Maxine in any dramatically substantial way. That does mean

they are not Tyrrell’s focus, but it also somewhat limits the intrusive gawking

Nevertheless, the limited-series clearly has some degree of sympathy for Carr, consciously

portraying her as a victim of abuse. For what its worth, Huntley looks

absolutely irredeemable right from the start and only gets worse as time goes

on.

In retrospect, local journalist Brian Farmer,

who acts as the conscience of the series, probably should have been its central

figure and protagonist. Ironically, he guilt-trips a bottom-feeding London tabloid

reporter for exactly the sort of sensationalistic exploitation the Maxine series

has been ripped for.

Jordan Peele's latest film exists in an

alternate reality where the Fry’s Electronic big box stores are still in

business. Unfortunately, the California-based chain closed in February 2022,

before filming even started. They blamed the pandemic, but it was really the

lockdown that killed them. More chaos comes to California, specifically

Hollywood ranch country, in Jordan Peele’s Nope, which screens during

MoMI’s Curator’s Choice series.

The Haywood family has handled horses for

Hollywood productions for years, but OJ and Emerald’s late father Otis Sr. was

the face of the business. Business has been off since he was fatally killed by

debris mysteriously falling from the sky. Since then, his adult children have

been forced to sell horses to Ricky “Jupe” Park, a former child actor, who now

hosts a western-themed amusement park. They have also lost horses to apparent

UFO abductions.

Emerald convinces O.J. documenting alien

activity could reverse their precarious fortunes. Naturally, they drop by their

convenient neighborhood Fry’s Electronic, where Angel Torres fixes them up with

surveillance gear. After installing everything, he taps himself in too, because

he wants to believe. Unfortunately, the supposed UFO always cuts electric power,

but he sees enough to officially team-up with the Haywoods, joining with them

to recruit acclaimed cinematographer Antlers Holst, who is famed for his

ability to get any shot. Holst also happens to own his own hand-cranked IMAX

camera, so he definitely has the right gear.

Peele spends a disproportionate amount of time

on Park’s backstory, particularly when his chimpanzee co-star went nuts a

killed the entire cast of his sitcom, leaving him as the sole survivor. It is a

masterfully brutal and surreal flashback scene, but it clashes with the

reserved emotional tone of the rest of the film. The metaphor also becomes

heavy-handed, when Park’s sense of his own charmed life leads to spectacular

tragedy. Nevertheless, it is some of Terry Notary’s most interesting simian work,

since The Circle.

Many pie-in-the-sky interpretive theories have

been applied to the sneaker seen balancing on its toe throughout the chimp’s

rampage. You name it, someone thinks it symbolizes it. However, the truth is

probably simpler (and sort of cooler). Peele produced the latest Twilight

Zone reboot, which several times referred back to Rod Serling’s original

series. Most likely it is an homage to the episode “A Penny for Your Thoughts,”

in which otherworldly things happen while a dropped coin remains standing on

its edge, where it landed.

Nevertheless, Nope, like Us, lends

itself more to creative analysis than his over-hyped Get Out, which is a

major reason why both are substantially superior films. Even though it looks

like an alien abduction movie, Nope is indeed a horror film, which Get

Out was not (it is a slightly fantastical thriller that is never really

scary). When it fully reveals itself, there is an atmosphere of menace to Nope

that is seriously creepy.

Carl Laemmle would be appalled to see

the Hollywood film industry he largely created now catering to the CCP regime,

at a time when it was committing genocide in Xinjiang—but maybe not surprised.

He truly was the only original mogul who criticized Hitler before the advent of

WWII. Unfortunately, he had already been forced out of Universal by that time. Filmmaker

James L. Freedman documents the mogul’s amazing life and career in Carl

Laemmle, which airs late-night tomorrow on TCM.

Born and raised in Laupheim, Germany, Laemmle

immigrated to America before Ellis Island was designated as a hub for new arrival

processing. After some scuffling, he entered the movie business when it was

still based on Nickelodeons and largely considered disreputable. A good portion

of Freedman’s doc chronicles Laemmle role as a scrappy trust-buster, breaking

Edison’s monopolistic hold on the motion picture industry. It is a good thing

he did, because Edison was dead-set against producing feature-length films,

whereas Laemmle was eager to push the envelope of film production.

With his son Carl Jr. in charge of production,

Laemmle’s Universal’s produced some everyone’s favorite films, notably

including the classic Universal Monster movies. That is exactly why a lot of

viewers will be turning in. Some might prefer a deeper dive into Universal

Monster lore, but the Laemmle doc still does them justice. However, Freedman

focuses his familiar talking heads (including Leonard Maltin and Peter

Bogdanovich) much more on Laemmle’s social and historical significance, first

as the David who took on Edison’s monopolistic Goliath and then as a critic of

Hitler and sponsor of Jewish refugees from Germany.

Tam always kept a good head on his

shoulders, until he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Now he keeps his head

on the body of a murdered assassin, thanks to the breakthrough technology of

“Uncle” Ma (who technically isn’t either). That muscle memory is a trip, but it

will be awkward when the dead man’s nasty associates will come looking for him

in Victor Vu’s Head Rush (a.k.a. Loi

Bao), which releases today on VOD.

Like Condorman’s alter ego, Tam used his superhero

graphic novels as his own wish fulfilment fantasies. He also wrote bizarrely

tragic historical epics about fathers dying in battle that will be little

comfort to his wife and pudgy son as they wrestle with his prognosis. However,

Uncle Ma has the technology. He just needs a viable body, which very

conveniently delivers itself, along with a hail of bullets from his murderers.

It is a good thing Tam and Ma happened to be in the right forest at the right

time, because they are able to sneak the body back to his lab for a head

switcheroo.

Suddenly, Tam knows Kung Fu, but his hands need

to relearn how to draw. He also might be getting flashes of the previous

tenant’s memories, especially when he visits a pretty young emergency room

doctor after some of his early heroics. Inevitably, Tam starts saving children

from burning buildings and the like. He also does a lot of parkour. However,

his new body won’t be so much fun when an organ trafficking gangster starts

threatening Tam’s family.

Since Charlie Nguyen ran afoul of the

government censors, Vu has assumed the responsibility of nearly single-handedly

driving Vietnamese film industry. He has been working his way through the

catalog of genres, so it was probably inevitable that he would give superheroes

a go. Frankly, the action in Head Rush is

pleasingly gritty compared to the films coming from the Hollywood legacy

corporations, including quite a bit of slickly choreographed gunplay.

The biggest drawback is Vu’s predilection for

melodrama, which remains undiminished in Head

Rush. Like clockwork, the film comes to a screeching halt so Tam’s wife can

lecture him about calling undue attention to himself or suspect him of getting

up to some hanky-panky with Dr. Young-and-Available. Seriously, give us all a

break. On the other hand, there are at least two wildly over-the-top third act

revelations that perfectly reflect the spirit of superhero comic books.

Trombonist Trummy Young played with Armstrong and Ellington, so when he partially-retired

to Hawaii, he naturally became the big jazz cat on the local scene. Naturally,

he would get the call for a jazz-themed episode of the original Hawaii

Five-O. He even has a brief speaking part, but the star of the episode is

jazz diva Nancy Wilson, who did a fair amount of guest shots during the 60s and

70s. Her best was probably the “Trouble in Mind” episode of Hawaii Five-O,

which airs Tuesday on Me TV Plus.

Wilson

plays Eadie Jordan, a popular jazz vocalist much like herself, but hopefully

not totally like her. She will be playing some high-profile gigs at the Waikiki

Shell with her pianist-musical director-ambiguous lover, Mike Martin, who was

just paroled on a drug charge. What McGarrett doesn’t know is that Martin has

always been clean. He just took the wrap for Jordan.

This

is a bad time to be strung out in the 50th State, where a batch of

lethally poisoned smack is in circulation. That is why Kono was casing the

little club Jordan and Martin came to score. Martin ends up cold-cocking him to

protect her, even though he knew it would jam him up with the law.

It

turns out square-looking McGarrett is an Eadie Jordan fan—a real fan who knows

every obscure record she cut. That changes the dynamics of tonight’s episode,

from a typical cops-versus-dealers story to a race to save Jordan from herself.

More than most episodes of the era, “Trouble in Mind” depicts drug addiction as

a health issue, just as much as a law enforcement problem.

In

fact, even the dealer who is the episode’s ostensive villainous figure is

surprisingly sympathetic—and ultimately almost as tragic a figure as Jordan. He

too is a former jazz musician, who boosts he still has his 802 Union card (the

New York musicians’ local).

Wilson

gives a truly bold performance as Jordan, probably drawing on the infamous

struggles of Billie Holiday and other musicians she may have known. She performs

bluesy renditions of “Trouble in Mind” and “Stormy Monday,” as well as a brassy

arrangement of “Spinning Wheel,” very much like the cover she released the year

before. Morton Stevens is credited with the music for this episode. Having

arranged for Sinatra and many of his Rat Pack fans, he clearly had a good feel

for old standards. This is definitely the “jazz episode” of Five-O,

because Wilson and Young are also joined by bassist Red Callendar, who also

gets a line of dialogue.

Inspector Dea Versini’s imaginary friend is sort of like Harvey, but instead of a

big white rabbit, “Jimmy” looks like a slightly cheesy James Bond knock-off. She

knows he really doesn’t exist, but he is a helpful sounding board when she

faces problems in her investigations or in her personal life. That happens

often, particularly with the latter. Of course, she tries not to advertise his

existence (in her head), especially not to her by-the-book partner in MHz’s new

French series Alter Ego, which premieres tomorrow.

Single-mom

Versini is a highly intuitive detective and a total mess in nearly every other

way. Fortunately, her long-suffering Captain (or whatever the French equivalent)

usually lets her work alone. However, he insists she partner up with Matthieu

Delcourt, a fast-tracked detective temporarily assigned from above. The chaotic

Versini and the meticulous Delcourt mix like oil and water, but there is also a

mutual attraction neither wants to admit. Yet, they wind up rolling together in

the back seat of Versini’s car late in the first episode, not that Jimmy judges

her for it.

It

is also obvious right from the start Delcourt has his own secret agenda. However,

he and Versini will still manage to clear new cases by the end of each episode—judging

from the pattern established by the first two.

The

pilot episode is surprisingly clever, using viewers’ expectations against them

when a muck-raking environmental journalist is murdered. Their second case hits

pretty close to home for Versini when a doctor is murdered at the hospital

where her husband works. That is how he refers to himself. Versini prefers the

term “ex-husband.” However, they still work together pretty well as parents.

The

whole imaginary friend thing sounds pretty shticky, like an early 1980s Tim

Conwy sitcom, but creators Stephane Drouet, Lionel Olenga, and Camille Pouzol lean

more towards neurotic deep dives into Delcourt’s subconscious, sort of like Play

It Again Sam, but Jimmy is a lot goofier than the Bogart Jerry Lacy played

in Woody Allen’s mind.

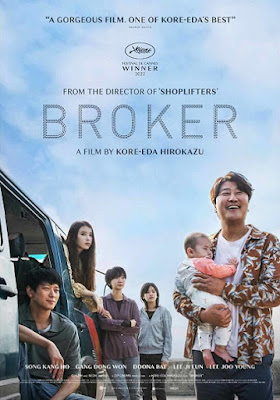

If you peruse the list of past Cannes Ecumenical Jury Award winners, some

of them might look a little forced. The truth is it can be tough to find films

that express the experiences and concerns of the Christian communities of faith

in major film fests, but Japanes auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest film was a

fitting selection. It might just be the most pro-life film ever—especially since

it was not conceived with the American Evangelical market in mind. More

importantly, it is a profoundly moving film that also won the Cannes best actor

award for Parasite’s Song Kang-ho. For his character, every unwanted baby

has value, especially those he can facilitate black market adoptions for in

Kore-eda’s Broker, which opens tomorrow in New York.

After

helming his first film in France with The Truth, Kore-eda shifts to the

current cultural capitol of the world, South Korea, for a tale inspired by the

controversial baby boxes, designed to safely accept unwanted babies, no

questions asked. The vast majority of such babies are placed in adopted home.

However, when the mother leaves a note promising to return, they are sent to an

orphanage instead—as sort of an escrow arrangement. The thing is the mothers

almost never really return, consigning their abandoned foundlings to orphan-limbo.

“For the sake of the babies,” part-time church employee Dong-soo erases the

records of those babies deposited with maternal notes, so baby-broker Ha Sang-hyeon

can facilitate a black-market adoption—for a fee of course.

Moon

So-young is the exception. The morning after leaving her baby, she returns to

reclaim him. Fortunately, He and Ha manage to intercept her. In his regular

life, Ha is a workaday hand launderer, but he is sufficiently persuasive to

talk Moon out of making trouble. In fact, he convinces her to help screen

prospective parents for her baby. However, on the first stop of their road

trip, they pay a visit to the orphanage that raised Dong-soo.

As

a result, Moon starts to understand his ill-concealed resentment towards her.

They also pick up a young stowaway, Hae-jin, who secretly joins their journey

out of a need for belonging. It is actually a caravan if you include the two

women are hot on their trail. Soo-jin and her junior colleague are detectives

hoping to catch Ha and Dong-soo in the act.

Broker

exemplifies

the humanism and forgiveness found in all of Kore-eda’s very best films. The

emotional pay-off lands brutally hard, but it never indulges in cheap

sentimentality. Kore-eda does not serve up a conventionally “happy ending,” but

he still takes viewers to a very uplifting place. This is one of Kore-eda’s

best films to date, ranking alongside the classic After Life. It is a

shame it is not getting the critical acclaim it warrants, probably because of

its pro-life implications.

Rest

assured, Kore-eda’s screenplay is never didactic, but over and over, his

characters argue every baby deserves a chance. Honestly, if the Evangelical community

does not embrace Broker, then go ahead and call them dumb philistines.

Homecoming is a staple theme of holiday specials, but unlike Pa Walton, this

unnamed Boy does not know where home is. Yet, he is determined to find it. His

journey will be more of a fable than an adventure, especially considering his ability

to talk to his animal companions in Peter Baynton’s The Boy, the Mole, the

Fox, and The Horse, produced by J.J. Abrams, which premieres tomorrow on

Apple TV+.

When

the Boy wakes up in the forest, he has no idea how he got there or where he

lives. Fortunately, he runs into the Mole, who has all kinds of helpful ideas,

like following the river to the human settlement. Initially, the Boy must

protect the Mole from the Fox, but when the little mammal frees his predator

from a hunter’s snare, he starts to trail after them, shyly. The going gets

easier once the Horse joins up with them, especially when they need a wind-break

from the storm.

Co-adapted

by Charlie Mackesy from his children’s book, The Boy etc. features some

platitude heavy-dialogue, by Tom Hollander manages to sell some of the

clunkiest, fridge-worthy banalities, with his warmly sensitive voice-over performance

as the Mole (he even sort of looks like a mole in real-life). It is sort of

like the Pooh stories at their most Taoist, pushing the envelope of New Age

schmaltz. However, the stylish animation, derived from Mackesy’s original

illustrations, is quite elegant.

Teenaged Shui Qing’s economically-stagnant industrial hometown was already

depressed and depressing. Imagine what it was like after the Xi lockdowns. She

could hardly stand any of it, including what passes for her family: a disinterested

father, an openly hostile step-mother, and her spoiled little half-sister.

Despite resenting her biological mother’s abandonment, Shui Qing can’t help be

seduced by her big city glamor and worldliness when the long-absconded woman reappears,

but their reunion leads to tragedy in Shen Yu’s The Old Town Girls,

which releases today on VOD.

We

can tell from the in media res opening things will work out badly for Shui Qing

and her mother Qu Ting. She left her daughter and workaholic husband to pursue

a career as a dancer in the cosmopolitan (by regional standards) Shenzhen.

However, she is back, hoping to raise money to pay off the loan sharks she

owes. Qu Ting never intended to visit her daughter, but their paths cross when Shui

Qing is banished from her home, while her step-mother’s parents visit.

Qu

Ting still isn’t exactly the maternal type, but she still worries about her

troubles sweeping-up Shui Qing as well, Yet, she sort of enjoys the attention

and the ability to mold her affection-starved daughter. Finally, Shui Qing

starts to feel better about herself, at least compared to her school friends.

Jin Xi so resents her well-to-do but constantly absent parents, she faked her

own kidnapping to get back at them. In contrast, Ma Yueyue’s mentally unstable

father is so poor, he almost allowed his boss to adopt her. The wealthy couple

still lobbying for “temporary” custody, which acerbates his mood swings.

In

some ways, the neo-noir elements at the beginning and end of the film might

feel at odds with the difficult mother-daughter drama that makes up its meaty

center. However, every bit of Old Town Girls is driven by the characters’

desperation, both economic and emotional. Shen pulls no punches depicting the

exploitation of contemporary Mainland society. For its Chinese release, she was

forced to tack on a “crime does not pay” post-it-note at the end, but there is

a glaring lack of criminal or “social” justice in the drama that unfolds

on-screen.

Hip horror fans know Brazilian horror icon Coffin Joe (Ze do Caixao) ranks alongside Freddy Krueger and Michael Meyers. I survey Ze's films and lasting significance at Nightfire here.

Jafar Panahi secretly finished his latest feature in May 2022. Two months

later, he was arrested again, after speaking out against the imprisonment of

his fellow filmmakers, Mohammad Rasoulof and Mustafa Al-Ahmad. Over the next

few months, Joe Biden shamefully responded by trying to revive the so-called “Iranian

Nuclear Deal,” potentially releasing billions of dollars in frozen Iranian assets.

We can only wish our government understood the Iranian regime as well as

filmmakers like Panahi and Rasoulof. Once again, Panahi serves up some

trenchant criticism of contemporary Iranian society, but with usual

compassionate humanism in No Bears, which opens tomorrow in New York.

This

time around, Panahi is surprisingly meta, both with No Bears in itself

and the film he is making within the film. The pseudo-fictional Panahi is

similarly banned from filmmaking in Iranian, but he is directing a new film

shoot in Turkey over Skype. The meta film chronicles the frustrations of an

Iranian dissident couple, attempting to arrange transit to continental Europe.

However, unbeknownst to his lead actress Zara, her on- and off-screen partner

Bakhtiyar’s dealings with Turkish underground passport brokers are actually

genuine, recorded documentary-style by Panahi’s assistant director Reza.

To

feel “close” to the action, Panahi has rented a cottage in a hardscrabble

Iranian border town. Of course, the villagers do not recognize Panahi, but they

can sense there is something secretive about him. Nevertheless, they show the

deference they believe is due to a man of his apparent education and class.

However, their hospitality turns frosty when Panahi unwittingly lands in the

middle of a potential family feud.

Apparently,

the family of Gozbal, a local young woman, is pressuring her to marry the man

she was promised to at birth, even though she loves Soldooz, a former student

who was expelled for participating in democratic protests. Everyone except

Panahi is convinced he accidentally took a picture of Gozbal’s secret

rendezvous with Soldooz, so he is constantly harassed by the aggrieved family

and the village chief for the proof. The more Panahi denies, the less polite

they get.

Even

if Panahi had not already been arrested for expressing solidarity with his colleagues,

No Bears (the title refers to the bogus reports of wild animals intended

to keep the villagers home at night) could have just as easily landed him behind

bars again. There are at least three reasons it would enrage the mullahs,

starting with the unflattering depiction of the traditionally Islamic, yet

superstitious villagers. It also explores the painful experiences of asylum

seekers, like Zara and Bakhtiyar. Seeing the former serving beers as a waitress

in a Turkish border town tavern would not help either. However, the biggest

issue would probably be Panahi’s continued resourcefulness defying their filmmaking

ban.

It

is also his best film since Taxi—maybe even his best film since Offside.

Sometimes meta-ness produces a hollow, over-intellectualized viewing

experience, but in this case, it deepens the drama and the resonance. This

might be a “fictional” film, but it is clearly very real in the mindsets and

realities it depicts.

Even if you don’t love horror movies, you have to respect the economics of

the genre. A lot of trashy slashers that weren’t exactly massive hits still got

sequels, because they were profitable. Arguably, the team behind the slightly-meta-anthology

Scare Package stay true to their love for VHS horror by giving us a

sequel. Of course, the main character, “Rad” Chad Buckley died at the end of

the first film, but there are always ways around that. Regardless, the Jessie

Kapowski, the final girl of the first film, must now survive Scare Package

II: Rad Chad’s Revenge, which premieres tomorrow on Shudder.

In

the first film, the constituent stories played out on the monitors of the Video

Emporium, Rad Chad’s horror specialty video store, but the framing device

eventually morphed into the final story. Buckley found himself trapped with

Kapowski and a notorious serial killer in an underground research institution.

She escaped with her life, but he was killed—or was he?

Everyone

certainly assumes he is dead when they arrive for his funeral in the opening

scene. True to form, he addresses his own funeral via videotape, much like

Randy Meeks in Scream 3. Then all heck breaks loose and Kapowski finds

herself in a Saw-inspired survival game, along with Rad’s Chad’s friends

and her mom (played by Night of the Comet’s Kelli Maroney, who brings some

terrific attitude and comedic timing in a key scene). In between challenges,

their Jigsaw-esque tormentor shows them VHS movies that we serve as the

anthologized stories. Supposedly, these now represent the 1990s, but viewers

will be forgiven if they can’t always tell the difference.

That

shift to the nineties is important for Alexandra Barreto’s “Welcome to the 90s,”

in which a serial killer starts killing the coeds residing in the “Final Girl”

house instead of the hard-partying sorority sisters of the “Sure To Die [STD]”

House next door. The premise is clever, but the hit-you-over-the-head execution

is not as funny as you would hope, which is a frequent complaint with Rad

Chad’s Revenge.

The

next installment, Anthony Cousins’ “The Night He Came Back Again Part VI: The

Night She Came Back” is itself a sequel to the previous Scare Package’s “The

Night He Came Back Again Part IV: The Final Kill.” It is probably the goriest segment of the

film, gleefully leaning into the escalating illogical chaos of slasher sequels.

The notion of a sequel within a sequel is quite sly, but slasher send-ups like

this are starting to all look the same.

Jed

Shepherd’s “Special Edition” holds early promise, fusing the tactile eeriness

of analog media with persistent urban legends regarding the supposed ghost of Three

Men in a Baby, but the payoff does not live up to the promise of the

set-up.

Inspector Jules Maigret was a rumpled, middle-aged detective and the unswervingly

faithful husband of Madame Maigret, but don’t compare him to Columbo. He might

be unassuming, but any dumb crook can tell the Inspector is nobody’s fool.

British actor Rupert Davies made that vividly clear with his portrayal of

Georges Simenon’s perennially popular detective in the early 1960s BBC series.

It was a hit at the time, but many episodes have been virtually unseen since

their original broadcast, due to the poor quality of the tapes. Happily, the

series has been restored to viewable condition (not perfect, but never headache-inducing),

with the first season releasing today on BluRay.

The

pipe-chomping Maigret is known for his compassion towards victims and criminals

alike. He understands only too well how human weaknesses and frailties can lead

to crime, even murder. However, he never plays it fast-and-loose with the law,

but he is happy to grant frequent breaks for a quick nip at the nearest bar.

That is why Sgt. Lucas is so loyal to his “patron” (or boss)—and why Lapointe,

the newest rookie in his department quickly shares his devotion.

Poor

Lapointe will be the focus of the first episode, “Murder in Montmartre,” when a

stripper he had carried a torch for turns up murdered. It is rather a

conventional procedural story, but the exterior location shots document the

Paris of the early 1960s that [probably] largely no longer exists.

The

second installment, “Unscheduled Departure,” based on the novel Maigret Has

Scruples, represents the sort of psychological gamesmanship, especially that

within families and marriages, that really distinguishes the series’ best episodes.

In this case, a man visits Maigret claiming his wife is trying to kill, based

on highly dubious and circumstantial evidence. Maigret is next visited by the

man’s wife, who claims he is going mad. With each subsequent visit, the stakes

and potential for murder rises, but technically, no crime exists for Maigret to

investigate.

“The

Old Lady,” “Liberty Bar,” “A Man of Quality,” and “The Mistake,” are all highlights

for similar reasons. They are not necessarily baffling mysteries to solve, but

rather it is Maigret’s ability to perceive, empathize, and back-of-the-envelop-psychoanalyze

that so compellingly drives the stories. Each episode is based on a Simenon

novel, so Giles Cooper and a battery of other screenwriters always stay rather

faithful to the source material.

“The

Burglar’s Wife” and “The Cactus” are also particularly amusing for the way

Davies embraces Maigret’s Maigret-isms. This is a surprisingly boozy show. It

is also very noir, especially compared to other British series of the era. Stylistically,

it bears some comparison to the iconic Peter Gunn. There is no real jazz

in in the 1960 series, but Ron Grainer’s melancholy French café-style theme is

distinctively catchy, almost becoming an ear-worm.

It

is a shame it took so long to clean up the tapes, because if this Maigret had

been available to PBS stations in the 1970s and 1980s, Davies’ Maigret would

have been as familiar to viewers as Leo McKern’s Rumpole or Roy Marsden’s Adam

Dalgliesh. Dozens of actors have taken their turn playing Maigret, but Davies’

take really inspires confidence. He is less flamboyant than Charles Laughton in

The Man on the Eiffel Tower (seriously, who wouldn’t be?) and less

hardnosed Jean Gabin in Maigret Sets a Trap, but “fatherlier” and

somewhat more “lubricated.”

Oliver is fortunate to be re-entering the world in 1987, having somewhat recovered

from witnessing the horrific death of his sheltering widowed-mom. If he were

released from his institution into today’s society, he would be constantly

admonished to admit his “privilege.” He is a good kid, but he has had a hard time

of it. When given the ultimatum: finds some friends or head back to institution,

he logically heads to the cemetery in Martin Owen’s The Loneliest Boy in the

World, which releases today on DVD.

Maybe

Margot, Oliver’s social worker, genuinely wants to help him, but Julius the

head-shrinker, only wants to confirm his negative diagnosis the court

disregarded when it ordered the boy’s release. Regardless, social services

apparently considers it perfectly fine for the teen to live by himself in his mother’s

retro-1950s house out on the outskirts of town. Seriously, the 1980s really

were totally awesome.

Charged

with proving his improved socialization, Oliver somewhat ill-advisedly digs up

the corpses of several recently deceased accident victims and takes them home

with him. Through some twist of magical realism, they transform into sentient

zombies overnight. Suddenly, the late Frank and Suzanne, who had nothing in common

during their mortal lives, are happy to act like picture perfect sitcom parents

for Oliver. The bratty Mel is now his cheerful little sister, Mitch is his new

best friend (who always sleeps over), and they even have a zombie dachshund.

None

of these transformations make sense—and screenwriter Piers Ashworth (working on

a story co-written with Brad Wyman and Emilio Estevez) never even tries to

explain any of it. Loneliest Boy is meant to be a fable and a bit of a

love letter to the 1980s. Weirdly, the film sort of works as both.

Simon Cross is a prime example of unrepentant “toxic masculinity.” He has also

saved the world several times over. You have to have a swaggering attitude and

a willingness to fight and kill to get the job done. Like Bond, he also enjoyed

his time with the ladies. His time has passed. Now the espionage game is played

by a more modern breed of spy, but when the world needs saving again, the

retired Cross will have to do it in Marc Guggenheim’s graphic novel, Too

Dead to Die, illustrated by Howard Chaykin, which goes on-sale today.

Cross

is rather disappointed in the current state of the world, considering all the megalomaniacal

villains he killed to protect it. Honestly, he does not even remember Liberty

Nuance, one of his former conquests when she comes to tell him something

important. However, he starts paying attention when a sniper kills her through

his window. She just barely manages to tell him the daughter he never knew they

had is in danger.

Immediately

reverting to his old ways, Cross detects signs of the involvement of his late

but not lamented nemesis Baron von Tsuma’s old Spectre-like group. After Cross

dropped him into a fiery volcano, the organization “rebranded” itself as an

international environmental science conglomerate. Cross’s daughter Lily Nuance

works for them. She has developed a radical scheme that could completely halt

the global warming process. The danger is not that Northshire Holdings will not

pursue her proposal—it is the certainty that they will—at the cost of billions

of lives.

It

is extraordinarily bold of Image Comics to publish Too Dead to Die,

given the way it portrays the mindset surrounding climate change issues. Yet,

there is a good point in there about applying cold, hard cost-benefit analyses

to climate policies, exactly like the Paris Accords. Regardless, the graphic

novel never gets bogged down in such dreary controversies. It is an unapologetic

romp, in the spirit of Bond-followers like The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and

Our Man Flynn.

Yet,

Guggenheim forces his larger-than-life hero to take stock of his life and

choices in rather thoughtful ways. The mere existence of his daughter is dose of

reality James Bond never had to face. Frankly, Guggenheim and Chaykin do a

better job modernizing their James Bond-like character than the woke signaling

coming from the current custodians of the Bond franchise—so maybe Hollywood

should start making Simon Cross films instead of potentially unrecognizable

Bond reboots.

Chaykin’s flashy,

splashy art perfectly suits the graphic novel’s rock’em-sock’em action. It is a

lot of fun, because it stays true to its roots, even while acknowledging the

inevitable passage of time. Recommended for all fans of super-spy affairs, Too

Dead to Die is now on-sale where books and comics are sold.

We do a terrible job teaching civics in the United States. When I say

terrible, I mean absolutely pitiful. If you did not already suspect as much,

this new game show will convince you. There is definitely room for a new

high-end quiz show in the tradition of Jeopardy. This isn’t it, but to

be fair, the participants probably suffer from dizziness induced by its human

roulette wheel format in creator-host Michael McIntyre’s The Wheel, the

American version of which premieres tonight on NBC.

McIntrye

has already had great success with the first three seasons of the original Wheel

in the UK. That is also why McIntyre is hosting the American version, instead

of Ryan Seacrest, or whoever. The structure is kind of clever. Six celebrity judges

are seated around the titular wheel and a randomly selected contestant pops up

from the middle. Each celeb functions as an expert in a given category. The

contestant choses a category and “turns off” whomever they think knows the

least about the subject. When the wheel spins, if it lands on the “canceled”

celeb, they lose their turn, but if it lands on the specialist, they win

double, if together they come up with the right answer.

Of

course, many of the categories are about inconsequential fluff like Beyonce

Knowles. When the category is something legitimate, like “elections,” the

results can get ugly—really ugly. They also lack a regular “expert” the show

can rely on for a snarky quip, like Paul Lynde, the perennial center square on Hollywood

Squares. On the first three episodes provided for review, pro-wrestler and

star of The Marine franchise Mike “The Miz” Mizanin probably

displays the slyest humor. Someone like Ben Stein could really add a lot to the

show, with his quick wit and command of what should be considered general

knowledge, but he probably wouldn’t be down for the spinning.

Roger Corman is a legend, but there were times when he was penny-wise and

pound-foolish. For instance, he never went to the expense of copyrighting his

1960 cult favorite, Little Shop of Horrors, which went on to inspire a

hit Off-Broadway musical, Frank Oz’s 1986 film adaptation, a short-lived

cartoon series, and a 2003 proper Broadway production. Currently, the Westside

Theatre has a new Off-Broadway revival running (resumed from its Covid hiatus),

which is suitably rambunctious for fans of the iconic story, in all its

incarnations.

It

is a tale Shakespeare could have told. Boy meets girl. Boy meets plant. Plant

eats everyone. Seymour Krelborn carries a torch for Audrey Fulquard, his

co-worker at Gravis Mushnick’s Skid Row florist shop. Unfortunately, she is

trapped in an abusive relationship with the sadistic biker dentist, Dr. Orin Scrivello

DDS. Mushnick’s is on the brink of closure, but the exotic cutting Krelborn nurtured

into a mutant-Venus flytrap-like botanical wonder creates a sudden media

sensation, reversing Mushnick’s fortunes. The problem is the unruly plant

Krelborn named Audrey II has an unquenchable thirst for blood. No longer

satisfied with the drippings from his pricked fingers, Audrey II demands a full

victim—and she is not shy about suggesting candidates.

This

is a familiar story for fans of B-movies and 1980s musicals, but the ensemble

throws themselves into it with admirable energy. Director Michael Mayer makes

the Westside stage feel as big as any Broadway theater. He slyly leans into the

horrifying aspects of Dr. Scrivello’s office, without actually getting

explicit. The production also has a clever retro way of acknowledging the

conductor-keyboardist, who also creates a surprisingly big sound.

This

is a Little Shop that celebrates the eccentricities of the show’s

original Corman source material, but Matt Doyle and Lena Hall are both sweet

and endearing as Seymour Audrey I. Andrew Call gets a lot of laughs as Dr.

Scrivello and in several other colorful smaller roles. Fans of the 1960 riginal

might miss Dick Miller’s Burson Fouch, the flower-eating customer and the

masochistic dental patient played by Jack Nicholson (and Bill Murray in the

1986 film), but Call’s crazy “cameos” help compensate.

I'm not in the business of advising drug cartels, but generally speaking,

when an old enemy like Michael Jai White goes off the grid, I’d let him stay vanished.

Instead, they go out looking for him for him where he is hiding-out south of

the border in R. Ellis Frazier’s As Good as Dead, written by its star,

Michael Jai White, which is now available on VOD.

Bryant,

a former cop and DEA agent, busted a drug-running and human-trafficking ring

run by corrupt copper Sonny Kilbane. Even though Kilbane is currently in

prison, he had his thugs go after Bryant and his wife, so he cut ties and

disappeared down to Mexico. He now works anonymously as a surveyor (a nice

detail), whose desert workout routines inspire straight-and-narrow Oscar, who

is bullied by his soon-to-be-paroled brother Hector’s fellow gang members.

Much

to his surprise, Bryant agrees to tutor Oscar in his distinctive Muay Thai-ish

style of martial arts. When the Mexican teen unleashes his sensei’s moves at an

underground steel cage match, some cell phone footage goes viral. Naturally, Kilbane

sends a team of assassins after Oscar, hoping to find Bryant. Unfortunately for

them, they will—but more hit squads will follow.

The

basic premise is pretty familiar to VOD action fans, but As Good as Dead has

two things going for it—and they are both Michael Jai White. As an action star,

he still has all his chops and looks just as chiseled as ever. He also wrote

some surprisingly clever lines, especially when he and Hector riff on action

movies. It is too bad there isn’t more of this attitude, because it really

helps elevate the film.

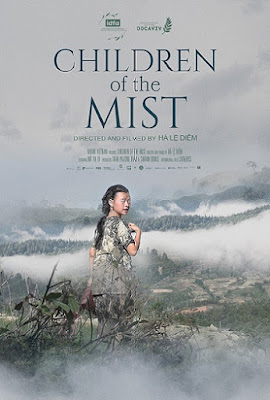

For Di, a young Hmong girl, growing up in mountainous North Vietnam is the

worst of two worlds. She gets all the pressure of online social media, but she

also must worry about the “traditional” bride-napping practice, usually targeting

girls around fourteen, just like her. Ironically, when navigating this difficult

societal terrain, she wears a red star t-shirt evoking her country’s notorious Marxist

revolutionary history. Ha Le Diem documents how hard it is to be a halfway forward-thinking

girl in her community throughout Children of the Mist, which opens today

at DCTV’s Firehouse in New York.

As

the film opens, Di and her friends playfully recreate a bride-napping, but she

assumes she is too headstrong for it to happen to her. Di actually wants to go

to school, but her parents are not so convinced she needs an education.

Whenever there is harvesting, she is expected to be there. That is also true

for most of her classmates, much to the annoyance of her didactic teacher, who clearly

has little patience for tradition.

Ironically,

Di is so modern in her thinking, she really doesn’t notice she is being

bride-napped, until it is too late. She just accepts a ride with Vang, a boy

from school, whose parents then tell her they are getting married now. Di is

not happy with that arrangement and neither is Ha, who seems more outraged than

Di’s dowery-formulating parents.

Mist

largely

starts as an observational ethnographic documentary, but down shifts into

something more urgent. While many previous docs have bemoaned the intrusion of

the “globalist” economy into remote traditional enclaves, especially when it

happens in the Brazilian Amazonia, Ha very pointedly introduces contemporary questions

regarding consent and equality.

This is the sort of film that makes you wonder what kid of elevator pitch the

filmmakers developed. Basically, it is a mockumentary creating the fictional

backstory of a semi-real internet hoax. It probably sounds exploitative, but it

tries to make all the right points about representation and agency of little

people. How well that works is debatable throughout screenwriter-director

Raphael Warner’s Lion vs the Little

People, which is now available on VOD.

At the end of Lion, the closing titles admit the expose the audience just watched is

fictional, but they maintain the pretense up to that point. Apparently, a phony

BBC news item really did go viral claiming 42 little people were killed in a

mysterious battle with a lion. Technically, it used the “M” word, which Warner

always scrupulously bleeps. The story (and it is a story) goes a dodgy FOB cardboard

magnate named Larry Vincent Ross created an underground little people fight

circuit in Macau, in partnership with a Chinese gangster with high-ranking CCP

connections. That part is pretty believable, especially the photoshopped

pictures of him with Bill Clinton. The TV ads he supposedly cut for his

ill-fated chain of dojos are less credible.

When the illegal fight circuit took off, Ross and

his associates escalated the action, pitting his little people fighters against

animals. Inevitably, things got a little too hot, so they decided to cash-out

with a big finale, but they had to lure legit little actors from Hollywood for

their battle royale against a lion.

Let me repeat: I am not making this up—but Warner

is. The film goes out of its way to use the right terms and criticize

stereotypes, but the fundamental premise is just about the most exploitative

thing you could imagine—and that is inevitably (if maybe unintentionally)

reflected in the one-sheet.

Yet, it has to be stipulated this is a work of

great chutzpah from Warner. Seriously, you have to wonder how he pitched this

film. Somehow, he even managed to recruit Linda Thorson (fondly remembered as

Tara King, Emma Peel’s successor on The Avengers) to play Gayle Bennet, the Hollywood casting director duped by Ross.

In 2018, the “Salisbury” poisoning attacks on Sergei and Yulia Skripal fatally

killed an innocent British subject, who had no connection to Russia whatsoever.

It was a pretty brazen assassination attempt on British soil, but obviously

Putin was not very impressed by the UK government’s response to his previous

hit-job executed in England, against a naturalized British citizen, back in

2006. Of course, the authorities had to provide some proof before taking

punitive action. That was the job of various detective and investigators of New

Scotland Yard, whose procedural work drives the four-episode mini-series, Litvenenko,

written by George Kay and directed by Jim Field Smith, which starts premieres

tomorrow on Sundance Now.

It

is spooky how much the once-and-future Doctor Who David Tennant looks

like Alexander Litvenenko, especially during his death bed scenes. The former

FSB agent and outspoken critic of Putin’s “mafia state” (his own term),

defected to the UK, becoming fully naturalized literally on the day of his

poisoning. Initially, the somewhat fictionalized DI Brent Hyatt is not sure how

to proceed, when the still living Litvenenko tries to report his own murder,

like Edmund O’Brien in D.O.A. However, the interview tapes he records

with the poisoned man supplied the foundation for the marathon investigation

that followed.

Hyatt

worked murders, which is a serious responsibility within the Yard, but a case

like this was transferred to Detective Superintendent Clive Timmons, who

oversaw the counter-terrorism office. He kept Hyatt and his DS attached to the

case, because the DI had cultivated the trust of Litvenenko’s widow, Marina,

and for his expertise investigating homicides. The case gets personal for

Hyatt, since he saw Litvenenko waste away in the hospital. He also has his own

scare, when the forensics department finally identifies Polonium 210 as the

lethal agent involved. It is one of the deadliest Polonium isotopes known to

man, but it is only produced in Russia.

Kay

and Smith do a remarkable job establishing the damning case against Putin,

without miring the series in minutiae. After watching Litvenenko, you

should be able to shut down any of his internet trolls who haven’t been drafted

to be cannon fodder in his invasion of Ukraine. Obviously, this is an opportune

time for series about Putin’s disregard for international law and human rights

to release. However, it is most of all a cracking good police procedural-geopolitical

spy thriller-hybrid.

For

a change, Neil Maskell gets to play an unambiguous good guy—and he is terrific

as Hyatt. The rapport he develops with Margarita Levieva playing Litvenenko’s

widow is quite poignant. The same is true for his unfortunately limited scenes

with Tennant in the doomed title role. It is sadly but necessarily a small

part, but Tennant is totally convincing. Frankly, they needed someone of his

caliber, to show how Litvenenko’s principled persona could take on such heroically

tragic proportions.

Thanks to Silence of the Lambs, dozens of subsequent movies and books featured cops

seeking the advice of convicted serial killers to catch newer psychopaths. In

real life, this sounds like an incredibly bad strategy, with little up-side. Regardless,

people still assume serial killers are all geniuses and the killers themselves

style themselves as transgressive artistes, when they are really just cruel,

anti-social murderers. The serial killer known as “The Artist” took it to

extreme levels. A frighteningly consistent copycat has adopted his M.O., but

seeking his insight turns out to be about as dangerous as a rational person

would suspect in Mauro Borrelli’s Mindcage, which releases Friday in

theaters and on VOD.

Before

he was captured and convicted, The Artist would pose his victims in

elaborate art installations that he called his “masterpieces.” Det. Jake Doyle

was part of the team that caught him, but his late partner was killed that

fateful night, in a bizarre, almost spoilery kind of way. Now he is working the

copycat case with Det. Mary Kelly, who will be the one visiting The Artist in

prison, because she has a psych degree and no prior history with The Artist that

he could use against her.

Of

course, he can miraculously tell Kelly where to find clues hidden within the

bodies and crime scenes. As the spectacular killings continue, the reluctant

authorities even start to consider cutting a deal with The Artist, but that

most definitely does not sit well with Doyle.

Mindcage

has

been billed as Martin Lawrence’s first role outside of comedy (assuming you do

not count Do the Right Thing, which would probably be his most

borderline previous film). The truth is, his performance as Doyle is the best

thing going for Mindcage. There is a big twist involving his character

that maybe you might guess or maybe you won’t, but he does a nice job reflecting

it on-screen.

Topic's THE SPECTACULAR is an politically astute thriller that does not white-wash the violence or extremism of the late 80s/early 90s Provisional IRA. Epoch Times exclusive review up here.

As they say on cooking shows, Ana Abramov has “knife skills.” She trained

at the Cordon Bleu and the KGB. When mobsters try to ruin her restaurant’s opening

night, she chops them instead in Zach Golden’s High Heat, which releases

Friday in theaters and on VOD.

Abramov

manages the kitchen, keeping a sharp eye out for broken sauces, while her

roguish older husband Ray spreads his smarmy charm around the

front-of-the-house. Their partnership works smoothly, until Mick and his goons

show up. It turns out, Ray maybe sort of borrowed money from Mick’s father Dom,

promising to repay it by torching the restaurant for the insurance money. Of

course, he neglected to tell his wife that part, but she skipped over her KGB

past too, so he figures they are even. He also assumed Dom would give him more

time to pay-off his debt, but something came up for the gangster, requiring

some quick ready cash.

Of

course, Abramov can easily handle the initial handful of thugs sent to firebomb

the place after closing. However, as Dom sends in more and more henchman,

Abramov calls in a risky favor from Mimi, her estranged former KGB partner, now

living as a suburban merc with her henpecked husband and partner, Tom. There is

a good chance Mimi might kill Abramov too. She’ll make up her mind when she

gets there. Regardless, Abramov can only really trust her husband. He might be

a screw-up, but they still have that spark.

High

Heat is

definitely a meathead movie, but it is a quality meathead movie. Olga Kurylenko

and Don Johnson are perfectly cast as the restauranteur couple and they share

some likable chemistry together. Dom and Mick are rather run-of-the-mill gangsters,

but Kaitlin Doubleday is spectacularly unhinged as Mimi. Likewise, Chris

Diamantopoulos counterbalances her as Tom, the bundle of nebbish neuroses she

deserves. (When watching High Heat, always try to remember Diamantopoulos

is the current voice of Mickey Mouse.)

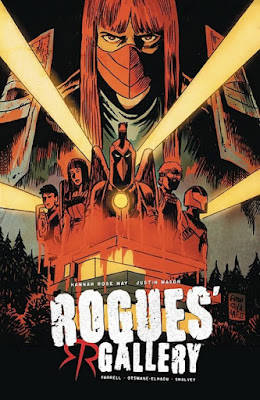

Cosplay is creepy. It is just supposedly grown-up fans, playing dress-up. Maybe

the X-rated kind has its place, but keep it in the bedroom and spare the rest

of us. If you disagree, the cosplaying home invaders terrorizing the

controversial star of their “favorite” superhero series should convince you. What

supposedly starts as a caped caper quickly escalates into a violent home

invasion in Hannah Rose May & Declan Shalvey’s Rogues’ Gallery, with

art by Justin Mason, which releases today in a tradepaper bind-up of issues one

through four.

Don’t

be fooled by the initial pages. They seem like a cheesy superhero story,

because they are scenes from Maisie Ward’s TV series, The Red Rogue,

based on a popular comic, but not sufficiently faithful for Kyle’s loudmouthed hate-watching

friends, Dodge, Yuri, and Haley. They are so mad about her diva-like control

over the series, they hatch a plan to teach her a lesson.

Teaming

up with “Slink,” a mysterious online troll, they plot to break into her

beachfront pad to steal a rare Red Rogue comic book. At least that is

what they tell the gullible Kyle. However, once they hack their way in, it

becomes obvious they intend to recreate a notoriously violent episode from the

comic.

May

gives the home invasion thriller an intriguing geek culture twist, but the

constant commentary on toxic fandom quickly grows annoying. It is clearly established

the anger directed towards Ward is misplaced, because it is the producers who

keep cheapening the property. Yet, in the real world, most fans disappointed with

the deterioration of Star Wars franchise, as one example out of many, mostly

blame Disney, producers like Kathleen Kennedy, and directors like Rian Johnson.