Statistics indicate most murders are committed by close friends or family members.

Jefferson Grieff agrees and he ought to know. The criminologist brutally

murdered and decapitated his wife. However, he is still accepting cases on a

special, limited-time-only basis, until his sentence is carried out. Perhaps

the Nero-Wolfe-on-death-row can save a woman an ocean away in Steven Moffat’s

four-part Inside Man, which premieres today on Netflix.

What

does a proper English vicar like Harry Watling have to do with Grieff? They might

just become fellow murderers, through an agonizingly torturous chain of events.

Being truly charitable, Watling took Edgar, a disturbed young parolee, into his

vicarage. Having too much sympathy, he agreed to hold Edgar’s flash drive full

of adult material so his domineering mother would not find it. Not really

thinking about, he took it home, where his son gave it to his math (or rather “maths”

since they are British) tutor, Janice Fife. Disturbingly, the models depicted

therein were decidedly not of age.

Fearing

for his son’s reputation but mindful of his vows, Watling tries to explain, but

the misunderstandings quickly escalate. Panic leads to further

misinterpretations and before you know it, Watling has Fife locked in the

cellar. So far, only journalist Lydia West suspects Fife might be missing, but

they only just met in the prologue, so she can’t credibly report her missing to

the police. However, she can ask the advice of her reluctant interview subject,

Grieff.

The

are two halves to inside man. One half features Grieff who is ruder than

Cumberbatch’s Sherlock, but let’s face it, he does not have much left to lose. Since

Grieff cannot have metal implements, he uses the photographic memory of fellow

convicted murderer Dillon Kempton as his note-taking device. Their Holmes-and-Watson

routine is jolly good fun to watch.

The

other half is the incredibly manipulative and uncomfortable Job-like plague of

troubles that rain down on the Watling family, who Moffat carefully establishes

are good, decent folk, simply to make Grieff’s point anybody can become a

murderer under the right circumstances. However, the succession of Rube

Goldberg-like one-darned-things-after-another that befall the Watley family are

wildly contrived, stretching believability past its breaking point. Witnessing

their anguish and desperation is no fun whatsoever. Making him a vicar really

feels like extra mean-spirited piling on, but admittedly, it adds further moral

dimensions to dilemma.

Stanley

Tucci chews the scenery marvelously as Grieff and his bantering chemistry with

Atkins Estimond, as the brutish but often quite witty Kempton, is thoroughly

entertaining. Dylan Baker is also terrific as Warden Casey, who is also rather

droll and cleverer than you would expect for government employee.

David

Tennant might be too good as Watling, because it is just painful watching him

implode. On the other hand, something about both Dolly Wells as Fife and

Lyndsey Marshal as Watling’s wife Mary seems off—like they constantly say and

do things to raise the stakes, elevate the pressure, and further confuse the

situation.

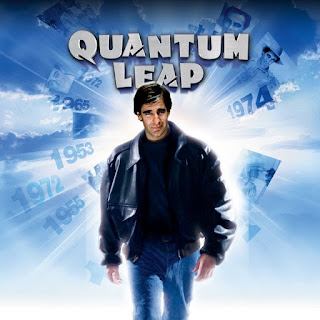

Dr. Ben Song is a man of science, but he is about to leap into a man of faith:

Father James Davenport, an exorcist, who failed to exorcise poor little Daisy

Grey. At least that was what happened in the pre-Leap timeline. Fans will

remember Dr. Sam Beckett maybe sort of had an encounter with Satan himself in

the first classic Quantum Leap Halloween episode, “The Boogeyman—October

31, 1964.” Perhaps it will be Dr. Song turn in tonight’s episode of the Quantum

Leap continuation series, “O Ye of Little Faith.”

As

Dr. Song enters the Grey household, the nine in their address shifts, becoming

an ominous “666,” which also happened at one point during “The Boogeyman.” Of

course, Song does not believe in demons, so he is pretty darned shock to actually

see the evil monster emerge from Daisy with his own eyes. Fortunately, he reads

Latin, because he will have to navigate this leap almost entirely without the

help of his fiancée and holographic guide, Addison Augustine, thanks to a

mysterious “glitch” in the system.

Instead,

Song (as Davenport) will rely on the assistance and counsel of Dr. Felix Watts.

Naturally, the doctor scoffed at the notion of the supernatural—until he gets

about fifteen minutes into this episode. However, he is rather impressed by the

way Father Davenport tries to apply the scientific method.

“The

Boogeyman” was a fan favorite episode, so it is cool to see the continuation

series pay homage to it in little ways. However, it does not explore the same

spiritual/metaphysical issues that episode raised. Of course, it has vastly

superior special effects and it is still pretty creepy. It also leaves us with

a bit of cliffhanger, but not one as significant as the one that ended “Salvationor Bust.”

Technically, Quantum Leaping is an act of possession. When you think about it, there should

be all kinds of moral ramifications to Dr. Sam Beckett’s time-traveling do-gooding.

Those were indeed addressed in the first Halloween episode of the original Quantum

Leap series, “The Boogeyman—October 31, 1964,” which is visually referenced

in tonight’s episode of the continuation series.

Before

Stephen King, Joshua Rey, was Maine’s best-known horror author. He is a bit of

a hack, but he is active in the community and a supporter of his local church. Every

year, he turns his home into a haunted house. Frankly, it looks like he already

owned most of the props and creepy trappings, but he shows them off to the

public for the Coventry Presbyterian’s annual fundraiser.

According

to Ziggy, Rey’s fiancée and research assistant, Mary Greely, will be killed

that night. Rey was the only suspect, but there was never enough evidence to

charge him. Sam assumes he is there to save her, but dead bodies keep piling up

in the meantime. Al Calavicci starts to suspect Greely, but Beckett just doesn’t

buy it. Red-headed Greeley, portrayed by Valerie Mahaffey of Northern Exposure,

just doesn’t strike him that way. In fact, something about this leap feels off,

even beyond the high body-count.

Quantum

Leap is

science fiction, but this episode totally embraces the horror genre, openly suggesting

something might have notice of Beckett. The ending is certainly ambiguous, but

it does not exactly walk back the supernatural implications of what viewer see.

This is not a Scooby-Doo-style ending, which is maybe why it became a fan-favorite.

This year, you can only watch It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown with

an Apple TV+ subscription, but you can finally hear all of Vince Guaraldi’s

classic music, in its entirety. For years, the audio masters were presumed

lost, so the previous 2018 soundtrack release simply dubbed Guaraldi’s themes

(along with accompanying sound effects) from the film print—which fans found

unsatisfying. However, the heirs of producer Lee Mendelson finally unearthed

the original music master tapes after their father’s death. Earlier this year, fans

finally got to hear the full Guaraldi soundtrack in the manner it deserved to be

heard. It is great jazz any day of the week, but you can’t beat the nostalgia

of listening to the soundtrack of It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown during

Halloween time.

Fittingly,

the soundtrack album starts with the classic Peanuts theme “Linus and

Lucy.” This take sounds somewhat different than that heard on the A Charlie

Brown Christmas record, because Ronnie Lang’s swinging flute is featured so

prominently, but it is still easily recognizable in theme and tempo as the Charlie

Brown music you know. The same is very much true of the “Charlie Brown

Theme,” appearing in several arrangements throughout Great Pumpkin, but

you won’t find that one on the Christmas record.

Ironically,

“The Great Pumpkin Waltz” is on the Christmas record, where it weirdly fits in

just fine, because it is such a lovely piece of music. “Graveyard Theme” might

sound like an incidental mood piece from its title, but it serves up a really slinky

groove with a cool bass line that stands alone quite nicely.

There

are a few pieces that mostly help listeners relive Snoopy’s antics from the

special, like Schroeder’s WWI medley. However, even Guaraldi’s “Red Baron Theme”

sounds pretty hip and swinging. Even the moody “Breathless” has a strong

rhythmic drive and Lang’s flute gives the second reprise a distinctive, exotic

flavor.

“Linus

and Lucy” “Great Pumpkin Waltz” “Charlie Brown Theme” and “Graveyard Theme” are

each repeated several times throughout the soundtrack album, including several

alternate takes. Yet, each rendition has sufficient variations to more than

merit their inclusion in the program (even the alternates are surprisingly good,

which is not always the case).

Admittedly,

Christmas is more traditionally associated with seasonal music than Halloween,

but it just seems like Fantasy Records left a lot money on the table not pursuing

a soundtrack album after It’s the Great Pumpkin premiered. Seriously,

how many copies of the Christmas album have they sold over the years? It even

features Monty Budwig on bass and Colin Bailey on drums (laying down a rock-solid

beat), who also played on some of the Christmas tracks.

At least it is here

now, but its not just nostalgia. It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown is

a great jazz album, from Guaraldi, who is still not fully appreciated as a jazz

artist. (For Great Pumpkin, he also had some notable assistance from

former big band lead John Scott Trotter orchestrating and conducting the score.)

Highly recommended for jazz fans, Peanuts fans, and trick-or-treats,

Guaraldi’s It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown soundtrack is now

available on CD, LP, and digital.

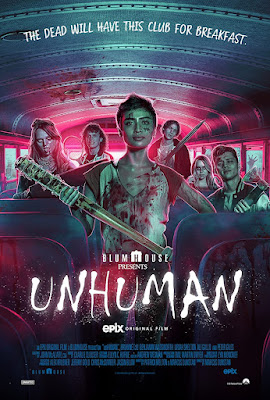

Nothing was scarier than the “Afterschool” specials of the 1970’s and 1980’s. They

were trying to terrify kids with the consequences of sniffing glue (and other

assorted vices), but they really just creeped us out with their manipulation and

corniness. This film is described, with tongue in cheek, as a “Blumhouse

Afterschool” special, but happily it is not as lectury as some of their recent

films (hello Black Christmas). Lessons will still be learned when Marcus

Dunstan’s Unhuman will be available on Prime as a regular SVOD title on

Halloween.

Poor

Ever knows her newly-popular lifelong-bestie Tamra is slowly withdrawing from

her and she will probably just let it happen. At least Tamra still sits with

her on the bus for the PTA’s latest feel-good, tree-hugging field trip. This

would be a heck of a time for a zombie apocalypse, wouldn’t it? It might be

more like a viral break-out, but something like that sure seems to happen.

Suddenly,

Ever and her surviving classmates are hiding in an abandoned institutional building

that looks like it has become a frequent site for raves. To get through this

crisis, she and Tamra will have to work with two role-playing geeks and some of

the jocks that bullied them. Alas, that might be difficult, because their prejudices

and resentments have become so ingrained and internalized.

Halfway

through, Dunstan and co-screenwriter Patrick Melton pull a carpet-under-our-feet

revelation that could have been an eye-roller, but they execute it quite

cleverly. They also largely avoid woke virtue signaling. In fact, some of the

snark coming from the field trip chaperone, phys ed teacher Mr. Lorenzo satirizes

that kind of kneejerk rhetoric quite cuttingly.

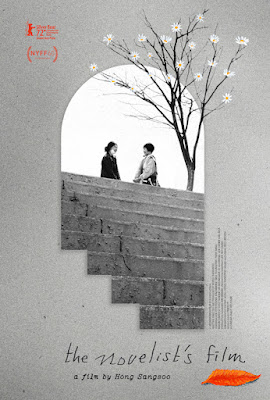

Novelists have a spotty track record directing films based on their own work.

Michael Crichton and Clive Barker did pretty well for themselves, but Stephen

King and Norman Mailer disappointed their admirers (but delighted fans of high

camp). It is hard to say how Kim Jun-hee might fare, because her filmmaking

goals and intentions are rather vague. That makes her a fitting protagonist for

Hong Sang-soo’s latest lowkey binge-drinking gab-film, The Novelist’s Film,

which opens today in New York.

Kim

ventured out of Seoul to visit her old friend Se-won, who now owns the local

independent bookstore. Their reunion catches Se-won by surprise. In fact, it is

somewhat awkward, but rather mildly so, by Hong’s standard. Afterward, she

visits the local scenic tower, where she coincidentally runs into Hyo-jin, a

director who once attempted to adapt one of her novels, but the project fell-through.

Again, it is awkward, but not outrageously so.

Strolling

outside in the gardens, they just so happen to run into Kil-soo, a thesp Hyo-jin

knows, who has put her career on hold, retreating to the peaceful calm of the

provinces. Kim did not know her before, but they get on like a house on fire—so

much so, Kil-soo agrees to appear in the yet to be conceived film the novelist

suddenly decides to make.

In

Hong’s previous films, coincidences were clever inventions that created their own

meaning. Unfortunately, the coincidences in Novelist’s Film simply come

across as humdrum occurrences necessitated by the relatively small cast of

characters. The wit is largely gone, but the neuroses remain.

Perhaps Lucy Chambers should have opted for the security of a freelance writing

career. That way she could go to bed at 4:00 AM. Instead, she wakes up each and

every night at 3:33 AM precisely. The stress from her work at Child Protective

Services probably does not help, but the phenomenon certainly seems to be

sinister and uncanny in nature at the start of creator Tom Moran’s The Devil’s

Hour, which premieres today on Prime Video.

“Gideon”

gives off Hannibal Lecter vibes during the in medias res opening. It appears he

is being held in-custody in a police interrogation room, where he has requested

Chambers presence, to explain all the madness viewers are about to watch. Rewinding

a little, we clearly understand how much stress Chambers is enduring.

Her

emotionally-frozen son Isaac is having very disturbing problems at school. For

instance, he beats himself up, because other boys told him so. He also often

exhibits spooky “shine”-like behavior, claiming to see people who aren’t there

and the like, especially around the time Chambers wakes each night. Isaac has

been a long-term issue in her life, but recently, Chambers has had premonitions

of the grisly murders of an abused wife and daughter, whose cases she handles.

Somehow,

those crimes that have not happened yet are related to the brutal case DI Ravi

Dhillon is working. There might also be a connection to a notorious local

unsolved murder that predates Dhillon. He is on the fast-track, but he still

has difficulty stomaching blood. Fortunately, his gruff but understanding

sergeant, DS Nick Holness, helps him cover as best he can.

Clearly,

Devil’s Hour is intended to be a mind-bending serial killer mystery

involving time-travel, or some kind of time-warping, much like Apple TV+’s Shining Girls. However, creator Silka Luisa did a much better job establishing the

ground rules in the early episodes. Based on the first two episodes provided

for review, it is hard to really understand what is going on, particularly where

Gideon fits into it all. Still, episode two, “The Velveteen Rabbit,” ends on a

heck of a cliffhanger.

Given

what we have seen so far, the procedural stuff is by far more compelling than

the melodrama involving Chambers and creepy little Isaac. Both Nikesh Patel and

Alex Ferns are terrific as Dhillon and Holness. If they survive season one, we would

be willing to watch further X-File-style investigations with their

characters.

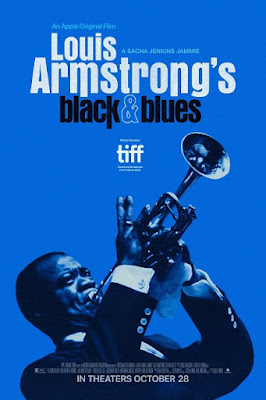

Decades after his death, this jazz legend returned to the charts when his songs “What

a Wonderful World” and “We Have All the Time in the World” were rediscovered. Both

the modern conception of the jazz solo and scat singing come from him. For these and many more reasons, nobody

is more iconic than Louis Armstrong, not even Elvis Presley or the Beatles.

There have been Louis Armstrong documentaries before, but there is always room

for another. Happily, director Sacha Jenkins does a nice job telling the jazz

legend’s story throughout Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues, which

premieres tomorrow on Apple TV+.

Shrewdly,

Black & Blues kicks-off with a performance of Armstrong’s “What Did

I Do to Be so Black and Blue,” a hard-luck blues that is widely interpreted as

a commentary on the racism Armstrong experienced. Jenkins definitely explores

those themes, without over-emphasizing the metaphor, with respects to that particular

tune.

The

story of Armstrong’s life will be familiar to jazz fans, but Jenkins covers it

well, giving viewers a vivid sense of his hardscrabble New Orleans upbringing,

his apprenticeship under King Oliver, and his breakout fame in Chicago. Frankly,

Black & Blues is surprisingly restrained when addressing Armstrong’s

relationship with his longtime manager, Joe Glaser, who has been widely criticized

as an exploiter by modern jazz historians.

Arguably,

Jenkins’ handling of Armstrong’s good will tours for the State Department and

his bitter criticism of Eisenhauer’s handling of the Arkansas school

integration riots is more nuanced than that found in the documentary TheJazz Ambassadors, or the nonfiction book, Satchmo Blows Up the World that

it was largely drawn from. Unlike previous sources, Jenkins suggests Eisenhauer

was waiting for someone prominent to speak out against Faubus barricading schools,

for some cover for Federal intervention (something I hadn’t heard suggested

before). Armstrong was the only one who did, but he was criticized in the press

by fellow celebrities, like Sammy Davis Jr.

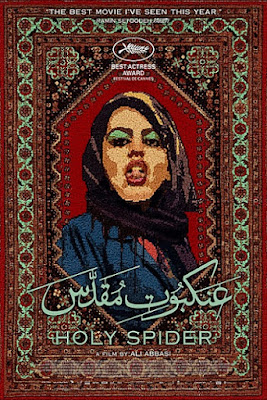

Saeed Hanaei was sort of like Iran’s version of Soviet serial killer Andrei

Chikatilo (a.k.a. “Citizen X,” who continued to kill over decades, because the

authorities deliberately ignored evidence linking his murders). Their prolific slayings

exposed the corruption and incompetence of the respective regimes. In fact, the

Islamist authorities were reluctant to stop the real-life Hanaei, for ideological

reasons, because he only targeted “fallen” women working on the streets of Mashhad,

the spiritual capitol of Shia Islam. Rather logically, it will be a woman

journalist who exposes him in Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider, which opens

tomorrow in New York.

Just

checking into a hotel in Mashhad is an ordeal for Rahimi, since she is a single

woman, unaccompanied by a man. She has to pull her journalist credentials,

threatening a scandal in the papers. Rahimi is here to investigate the “Spider

Killer,” since the local authorities clearly lack a sense of urgency.

To

make matters worse, Rahimi’s bad reputation (quite scandalously, she filed a

sexual harassment complaint against her former boss) has followed her to

Mashhad. Nevertheless, Sharifi, the cautious local reporter who has received boasted

calls from the killer agrees to help her investigation. However, winning the trust

of the city’s prostitutes will be very difficult. Yet, they keep coming home

with the murderous Hanaei, because that is what their business requires.

Holy

Spider is

Columbo-like in the sense that it reveals Hanaei’s identity as the

killer right from the start. Abbasi also vividly depicts in his brutality, in

stark, uncompromising terms. The misogyny of Iranian society also comes through

loud and clear, especially during a scene in which Rahimi barely escapes an

attempted sexual assault, at the hands of Mashhad’s police chief. For a so-called

“holy city,” Mashhad looks like a pervasively predatory environment.

Yet,

the investigation is only half the story. The rest of the film consists of the

trial, wherein Hanaei tries to ride his public popularity to an acquittal, on

the grounds his murders were theologically justified. Much to Rahimi’s concern

and disgust, there is a very real chance Hanaei could pull it off.

For

obvious reasons, it was Denmark that selected the Danish-based, Iranian-born

Abbasi’s film as its International Oscar submission, rather than Iran. However,

Abbasi filmed on location in Jordan, which doubles convincingly for the grim,

dark streets of Mashhad (at least for viewers who have never visited, but have

seen a number of Iranian films).

Holy

Spider is

definitely a visceral indictment of institutionalized injustice, intolerance,

and sexism in contemporary Iranian society. However, it is also a potent hybrid

serial killer thriller and courtroom drama. Indeed, the uniquely perverse aspects

of Iran’s justice system greatly complicate the prosecution and consequently generate

greater suspense than an equivalent case ever could, in just about any other

jurisdiction.

In

a performance of great personal courage (considering the possibility of subsequent

reprisals), established Persian thesp Mehdi Bajestani is frighteningly intense

as Hanaei. It is not the physical violence that makes him such a monster. It is

his absolutely conviction in the righteousness of his murders.

These American troops stationed in Afghanistan will find themselves in a tight

spot. It is not as difficult a position as evacuating from Kabul airport after

Biden shutdown the Bagram airfield, but it is still really bad. Along with a

downed RAF officer, they find themselves stuck between Taliban insurgents and

mutant monsters in Neil Marshall’s The Lair, which opens Friday in New

York.

Lt.

Kate Sinclair is a pilot, but she and her weapons systems officer fight like

heck after their jet is shot down by the Taliban. Alas, he won’t back it, but

somehow, she manages to take shelter in an old subterranean Soviet military

installation. The Taliban were bad, but the monsters she sees down there really

freak her out.

Sinclair

is the widowed mother of little girl, so she finds a way to survive. However,

the remote American outpost that takes her in is skeptical of all her monster

talk, except maybe Major Roy Finch. It seems to ring a bell for him. Of course,

when the creatures attack, they will ring a lot people’s bells.

Apparently,

this all the result of some seriously evil Soviet military experiments. Easily

the coolest idea Marshall and his co-screenwriter-lead thesp wife Charlotte

Kirk come up with is the notion the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was really

all about recovering and exploiting an alien UFO crash site.

The

down side is the film’s cynical depiction of the American military. It is

insulting to suggest a corporal would steal from a British officer in distress.

Similarly, it is unlikely the most dysfunctional and disgraced officers and

enlisted men serving in-theater would all be transferred to the same outpost,

in the middle of insurgent territory.

Compared

to The Reckoning, Kirk’s previous film with Marshall, The Lair is

a much better showcase for her. It certainly helps than she is more restrained

and at least a little more glammed down as Sinclair. Most of the other soldiers

are not given much by the way of personality, at least on the page, but Jonathan

Howard and Leon Ockenden manage to invest some into Sgt. Tom Hook and Sgt. Oswald

Jones, another lost Brit. Jamie Bramber is also entertainingly grizzled as

hardnosed, hard-luck Maj. Finch.

Neither your parents or your teachers probably ever taught you the etiquette of

hauntings, either for the haunted or the haunter. Maybe the Church and horror

movies gave us a clue, but that was only for really adversarial hauntings. It

is therefore rather understandable that Clay would be confused when his old

friend Whit starts haunting him in Clay Tatum & Whitmer Thomas’s The

Civil Dead, which screens during this year’s Terror-Fi.

Clay

is an under-achieving photographer, who fortunately lives with his gainfully

employed wife. Whit was a struggling actor, who apparently will never make it,

because he is now dead. Clay is rather surprised to run across him in the park,

but Whit is even more surprised, because he had resigned him self to being a

spectral ghost nobody can see.

It

takes a little convincing, but eventually Clay concedes nobody else can see

Whit, so it sures seems like he most be dead. It is a lot to process, but Whit

still latches on hard, because his is so relieved to finally have company.

Somewhat ironically, Whit had ghosted Clay during their senior year of high

school and Clay had largely ghosted him back after they both moved to LA, where

Whit was desperate for some sort of social support, so their relationship was

already awkward. Death and haunting will start to realty make it weird.

Civil

Dead is

the sort of hipster horror comedy some of Onur Tukel’s darned-near unwatchable

films were supposed to be, but weren’t. The screenplay, co-written by Tatum &

Thomas is intensely neurotic, but there are also some genuinely creepy moments.

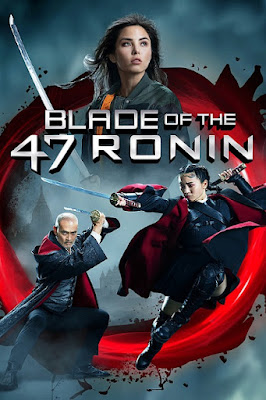

It is pretty clear from this film, Samurai are far more skilled than

ninjas. However, ninjas attack with superior numbers, like in the dozens or

hundreds. Those ninjas hordes obey the commands of a witch who has targeted the

descendants of the loyal samurai-turned-ronin, who avenged their lord back in

the Edo era. It is about as loose as sequels get, but the hack-and-slash

martial arts certainly entertains throughout Ron Yuan’s Blade of the 47

Ronin, which releases today on DVD and Netflix.

Supposedly,

this is a sequel to the disastrous Keanu Reeves version of The 47 Ronin,

but feel free to pretend it is a sequel to the Kon Ichikawa or Kenji Mizoguchi

adaptations, because the connection between films is tenuous, at best. In the

present day, samurai clans operate in secret, based in Budapest, supposedly

because it is a key juncture between East and West, but it also happens to be

affordable to shoot there. The descendants of the 47 Ronin guard the magically

divided half of a mythic sword that holds a fateful prophecy. The witches

hold the other half, but Yurei, the most powerful warlock has gone rogue.

He

thought he had killed all the Ronin’s descendants, but there was a secret

progeny out there somewhere. Unfortunately, the punky, resentful Luna does not

inspire much confidence. She has come to Budapest to sell her late, estranged

father’s sword, which is obviously priceless. Luna is a pain, but virtuous Lord

Shinshiro protects her anyway. That duty primarily falls to his Bugeisha (samurai

warrior woman) Onami, who enlists help from her old confidant, Reo, a ronin,

who was forced out of Shinshiro’s service due to a past disgrace.

Scholars

of Japanese history and literature will probably be scandalized by the way Blade

trades on the names of the 47 Ronin, which is fair enough. However, if you

accept the film as its own stand-alone entity, it is pretty fun, admittedly in

a meathead kind of way. Ron Yuan (the actor, not appearing in-front of the

camera this time around) clearly understands how to frame a fight scene and he

is not intimidated by a little blood splatter. The swordplay is often brutal,

but it looks great.

Yuan

also has the benefit of two major action stars, who still clearly have their

stuff. Mark Dacascos is cool and commanding as Lord Shinshiro, while Dustin

Nguyen is all kinds of steely playing Lord Nikko. Stylistically, his clan is

very different from Shinshiro’s but they are allied in honor. They both have

plenty of highly cinematic fight scenes, but Teresa Ting and Michael Moh (Bruce

Lee in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood) have even more. Their athleticism

is impressive and they some appealing comrade-in-arms rapport going on.

Walter De Ville’s stately New Carfax Abbey does not look very new, but if you

remember who in horror fiction owned the old Carfax Abbey, you can understand

why he would make the distinction. The Stoker references will continue to

pop-up in Jessica M. Thompson’s The Invitation, which releases today on

DVD and also opens Thursday in Brazil (Brasil).

After

her mother’s death, Evie Jackson is alone in the world, except for her tiger-mom-ish

best friend Grace. Then she took a free genealogy test that surprisingly told

her she had a bunch of very rich and very white relatives in England.

Apparently, there was a scandal with a footman, way back when. Weirdly, the

Alexanders are strangely psyched to meet her. Suspiciously friendly Oliver

Alexander even offers to fly her out to an upcoming family wedding.

The

ceremony will be at New Carfax, hosted by their long-time family friend, De

Ville (do you hear what his name sounds like?). The exacting snobbery of De

Ville’s butler, Field, rubs Jackson the wrong way, but the gracious lord of the

manor smooths thing over. In fact, he launches a charm offensive that Jackson

does not entirely discourage. It is all pretty overwhelming for the poor

orphan, especially the elegant, bullying bridesmaid, so she does not notice how

many temp-maids keep getting murdered.

Real

genre fans should know they can get the killings with a little more violence with

VOD and DVD releases, compared to the PG-13 theatrical release. Anyone with any

pop culture literacy can guess De Ville’s deal. However, Thompson devotes so

much time to his courtship of Jackson, it starts to feel more like a regency

romance than a gothic supernatural yarn. Also, the concessions to class warfare

and gender-politics are shallow distractions that will badly date Invitation

in the years to come—“vampire at-large, women and the working-poor hardest hit.”

As society becomes increasingly cashless, dead folks no longer have coins

to pay the ferryman to the other side. There are several symbolic references to

that old myth in this mystical thriller—or is that gold coin more than merely emblematic?

Elliot physically happens across it after checking into a strange dessert

motel. The woman in the room next door looks a heck of a lot like his wife

Julie, but she insists she isn’t. That is the kind of self-consciously Lynchian

ride we’re in for during Chris Chan Lee’s Silent River, which releases

today on VOD.

Elliot

seems to have a lot of blood on him when he checks in. He also has a suit case

full of his wife’s clothes. The woman in the connecting room looks a lot like

Julie but she says she is Greta. She also claims Patrick is her husband. He is

dead, at least for now, but she has his android-automaton ready for some kind

of exchange. It is hard to say what is real and what is illusion, not even

Elliot’s visions of a Minotaur roaming the halls of the motel.

Yes,

Silent River is definitely that kind of film. It is always risking to

lean so heavily into secret world-beyond-our-own spiritual mumbo jumbo—just look

at Adam Sigal’s Chariot or, saints in Heaven protects us, Timothy

Woodward Jr.’s Checkmate (but the ultra-micro-budgeted Mystery Spot largely

pulled it off). Silent River is a bit more disciplined, but it is also

much slower getting started. Viewers basically tour every inch of the motel

during the sluggish initial half-hour.

Chad Thadwick and his best stoner pal Eddie make the amateur

podcaster-sleuths of Only Murders in the Building look like Sherlock

Holmes, Nero Wolfe, and Miss Marple. The lads are a bit dim-witted, even when

they haven’t been hitting the bong. Nevertheless, their ill-conceived attempt

at true crime podcasting uncovers a sinister supernatural entity in

director-screenwriter William Bagley’s The Murder Podcast, which

releases Wednesday on VOD.

Thadwick’s

current podcast, “Ramen Reviews with Chad Thadwick” is attracting about as many

listeners as you would expect. (Keep in mind, his ramen is strictly the cheap

store-bought kind, not fine dining ramen.) After his impatient brother-in-law

raises his rent, Thadwick convinces his sidekick Eddie to switch formats to criminal

investigation. Conveniently, his quiet suburban town just had its first

suspicious death in years. Officer Stachburn assures the media the victim’s

head simply popped off accidentally, as the result of a freak fall, but even an

idiot like Thadwick can tell that’s bogus.

Viewers

know from the prologue, the first victim brought the spirit of an angry witch

home with him, after he stumbled across her grave during a hike. The moron took

the coin off her tombstone, which had sealed her inside the tomb. Naturally,

she starts bumping off victims, as that coin passes from hand to hand.

You

can often see how hard Bagley is trying to entertain horror fans throughout Podcast.

As a result, many of the bits feel rather forced. However, some of the gags

manage to connect, especially when ramen suddenly becomes relevant to the

narrative again, thanks to its high sodium content. On the other hand, the lore

surrounding the witch is better developed than the usual bogeymen of most

horror-comedies. Weirdly, some of the “straight” material helps retain viewers,

like the revelation Thadwick’s disgraced conspiracy-mongering father tried to

expose the witch during her last killing spree, at the cost of his credibility.

Apparently, Generation X is now just barely old enough for significant events from

our teen years to appear in time travel shows. In fact, the Quantum Leap continuation

series is appealing to those memories quite effectively. During the premiere episode, it was Live Aid. Now, Dr. Ben Song leaps right into the middle of the

1989 earthquake. We don’t have much nostalgia for that one, but the shock of

how it disrupted the Bay Area World Series comes back vividly. Given the

circumstances, Song has plenty of people to help in tonight’s Quantum Leap episode,

“What a Disaster.”

If

you missed “Salvation or Bust” last week, “Disaster” starts with the

cliffhanger ending to the previous episode, which was a game-changer. Apparently,

there is another leaper, who recognized Song and wasn’t too happy about it. Addison

Augustine, Song’s holographic guide also saw him, so she will get Magic

Williams’ team in the present-day working on an ID. Song has to concentrate on finishing

his leap, presumably by saving John Harvey’s son. To do so, he and Harvey’s

wife, Naomi Harvey, must travel from their current home in San Francisco to

their old apartment building in Oakland, where their homesick son ran off to at

the mother of inopportune times. Ironically, it is probably more dangerous to

make this trip in broad daylight today than the night of the 1989 earthquake.

This

episode clearly leans into family themes, in ways that stir memories of the

amnesiac Song’s childhood that he never confided to Augustine before. “Disaster”

does a nice job addressing the Harvey family’s issues, without glossing over

messy complications. Song won’t fix everything, but maybe getting them back on

a workable track.

“Disaster”

also gives viewers an inkling of some of the mind-bending time-travel issues

that might be coming down the road. Although it is not clear, there is reason

to suspect the other leaper is from the future—relative to the present Williams

and company operate in. As of now, “Leaper X” seems pretty cool and his record

is faultless, so how and why is he leaping?

The World Cup should have already happened this year, but because FIFA is

hopelessly corrupt, they chose the inferno-like Qatar to host this year, during

the still scalding hot month of December. To tide football fans over, Matthew

Bate & Case Jernigan explore the social significance of the game and the

super-fandom it inspires in their animated five-mini-episode A Game of Three

Halves, which premieres Wednesday on OVID.tv.

It

is surprising how timely this mini-mini-series turns out to be. The second (and

best) episode, addresses the Iranian regime policies prohibiting women fans

from attending football matches, at a time when Iranians are taking to the streets

to protest the suspicious death of Masha Amini. The fourth episode chronicles

the cave rescue of the Thai school children’s Wild Boars FC soccer team and how

the story captured the attention of the football world, during the 2018 World

Cup, a story now familiar from a recent crush of films and documentaries.

Each

episode is a mere five minutes in length, give or take, but they are all quite

funny and rather perceptive. Journalist Max Rushden amusingly explains the

trials and occasional triumphs of amateur weekend football warriors in the

opening “Where the F%*ck is Hamish?,” titled in honor of the annoyingly

irresponsible player every team has, who always gets away with his flakiness,

because he is so good.

“Sara,”

written by a real Iranian fan, under the eponymous pseudonym, is the best of the

bunch. It forthrightly addresses the misogyny and inconsistency of the regime’s

policies, but in a surprisingly light-hearted way that makes it a good

companion piece to Jafar Panahi’s Offside.

Jonathan

Wilson’s offers some rather clever observations on the neurotic nature of

goalies in “Keepers.” It turns out both Nabokov and Camus played in goal, which

definitely reinforces his point.

Joel

Colby’s “All Hail the Wild Boars” is the shortest of the dozens of recent releases

chronicling the Thai cave rescue. Its brevity is part of its charm, but it also

has a fresh perspective.

According to this anthology, Tiktok is evil (which is definitely true), but Clubhouse

is good. The evidence for the latter is inconsistent, based on the following

tales, conceived and directed by community-members using the audio app. However,

the song linking most of the stories together is rather catching, in a sinister

kind of way. The “Fortress” theme repeatedly pops-up in Sinphony, which

is now playing in theaters and on-demand, following its premiere at the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival.

Things

start with a merciful brief birth gone-very-wrong that introduces the “Fortress”

song and a rather malevolent healthcare worker, before the first proper constituent

tale starts. Wisely, Sinphony starts with the best of the lot (but that

also means it is all downhill from here). Fittingly, Jason Ragosta’s “Mother Love”

features a coven of witches using a Clubhouse like app. Unfortunately, one of

them must protect her young son from a serial killer preying on her witchy

kind, while her sisters listen in. It is a tight and tense combination of home

invasion and witchcraft horror that puts fresh spins on both.

Steven

Keller’s “Ear Worm” offers up some standard body horror, but the set-up is

pretty good. The anthology rebounds with Haley Bishop’s “Forever Young,” which

is probably the most zeitgeisty story in Sinphony. Not thrilled to be

turning thirty, a not-as-cool-as-she-used-to-be woman tries to prove her

hipness with the latest Tiktok like dance video app. The ironic results are

horrifying. They also reflect the fears that are now pervasive in society of

the way social media and big tech censors, silences, corrupts, and manipulates

us.

Unfortunately,

“Forever Young” represents Sinphony’s second and final notable peak.

Kimberly Elizabeth’s “Do Us Part” is a somewhat successful depiction of a dead

wife haunting her mourning husband, but it plays more like a darkly comic

sketch. There is a lot of potentially interesting stuff in Mark Pritchard’s “Limited

Edition,” but it does not have sufficient time to establish and explain its

supernatural elements (including a mysterious text that reappears in later episodes). Frustratingly, it leaves the audience wondering: “huh,

wha?” (Still, there is something intriguing about this installment that cries

out for fuller feature-length treatment.)

Wes

Driver’s “The Keeper” is anchored by such a nice performance from Ronnie Meek

as the Innkeeper in question, it keeps viewers hooked, even though we can guess

the secret the new family that checked-in is hiding. In contrast, there is not

much suspense to Jason Wilkinson’s grim “Tabitha” chronicling a woman’s final

moments after she was shot fleeing a crime, while she faces her real and

metaphorical ghosts.

Jess Whitman and her high school friend Alana Wheeler were good witches, but not

like anything you have seen in Bewitched or on the Hallmark Channel. Despite

their power, life still dealt them some tough cards. When they dabble in some

dangerous magic, the consequences are profoundly dangerous in Terence Krey’s Summoners,

which premiered at this year’s Brooklyn Horror Film Festival.

Whitman

rarely returns home after college, but for some reason she suddenly felt

compelled to visit her widower father Doug. It will start to make sense when

happens to run into Wheeler. They had practiced magic together in high school, until

the death of Whitman’s mother left her disillusioned with witchcraft and the idea

of the supernatural in general. Whitman has yet to properly deal with her

mother’s passing, because she knows her mom had been unfaithful to her father at

the time—but she never knew if he knew.

Wheeler

more or less admits she “called” Wheeler home, hoping she would help with a

serious ritual. She wants to summon a “sin-eating” spirit to give some relief

to a friend. Of course, any tormented entity carrying that much pain and resentment

is going to be angry and difficult to control.

Summoners

builds

on and surpasses the psychologically complex horror Krey developed with his

partner and on-screen lead Christine Nyland in their first feature, An Unquiet Grave. Both films deal frankly with guilt and grief, with more

sophistication and empathy than anything A24 has ever released. Viewers really

feel for these three major characters, but Krey still takes care of the horror

business. The film is largely built around several spell-casting rituals that

are all highly atmospheric and increasingly ominous.

Today, nontraditional productions of Shakespeare are more traditional than

stagings that maintain the original eras and settings of his plays. That was

not true in 1936, when Orson Welles directed a Federal Theatre production of the

“Scottish Play” in Harlem. Instead of Scotland, it shifted the action to Haiti,

where voodoo substituted for Celtic witchery. A platoon of ten directors and

eight screenwriters recreate the behind-the-scenes drama in Voodoo MacBeth,

which opens today in New York.

The

public did not recognize Welles as a golden boy yet, but producer John Houseman

had an inkling of his talents. However, Welles was first somewhat reluctant to

tackle MacBeth with an all-black cast, but his first wife Virginia convinced

him of its potential. Of course, he was already Orson Welles, by temperament,

so he frequently clashed with Rose McClendon, the founder of the Federal

Theatre’s Harlem division, who had originally cast herself as Lady MacBeth.

Casting

the rest of the roles was tricky, but Welles saw a spark in former boxing champ

Cuba Johnson, who is transparently based on the production’s real-life Banquo,

Canada Lee—but the twice-married welterweight might well be surprised by

Johnson’s cautious coming-out and tentative gay relationship with another

cast-member. Meanwhile, Houseman must battle Rep. Martin Dies, the first chair

of the House Un-American Affairs Committee for founding of their radical

production.

The

caucus of directors and screenwriters eagerly positions Dies as the film’s

villain, but it conveniently forgets the local Communist Party violently

picketed the production. Welles would have sliced and diced by an attacker,

were it not for Lee’s timely intercession. Nevertheless, their Voodoo

MacBeth film will inevitably be panned for giving Welles and Houseman

prominent “white savior” roles, because cultural criticism has collectively

lost its mind. Seriously, this would never have been picked up for distribution

without Welles’ central role—and I probably wouldn’t be reviewing it.

Jewell

Wilson Bridges and Daniel Kuhlman are both reasonably solid as Welles and

Houseman, but they lack the flair and physical resemblances Christian McKay and

Eddie Marsan brought to the famous collaborators in Richard Linklater’s unfairly

overlooked Me and Orson Welles. Frankly, Bridges just lacks that

Wellesian charm.

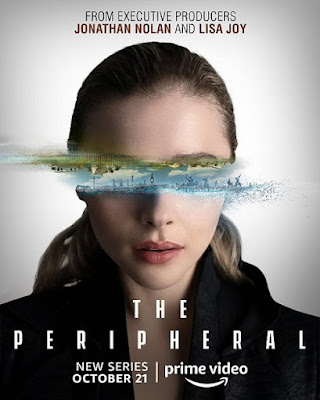

Flynne Fisher neither lives nor travels into the Matrix. She is in the real

world when she puts on an experimental headset and she still is when it digitally

transmits her nearly seventy years into the future. When she gets there, she is

not remotely controlling an avatar. She has a physically constructed

peripheral. She thought she was testing a game, but the story she is playing

will actually happen IRL. It will also reach back into the past (from the

future’s perspective, or the very-near future to us) to target her and her family

in creator Scott B. Smith’s The Peripheral, based on William Gibson’s

novel, which premieres today on Prime Video.

Fisher

is a gifted gamer, but she is too grounded in her day-to-day reality to retreat

into cyberspace. However, she often ghost-games on her brother Burton’s behalf,

when he has high-paying gigs. Technically, he was the one hired by a mysterious

start-up to test-drive what the Burtons assume is a new VR headset, but she is

the one who ventures into the “game.”

It

feels really real in this somewhat-far future London, because it is. Initially,

she enjoys the intrigue instigated by her in-world guide, Aelita West, but it

takes a dark turn during her second visit—very dark. Fisher vows never to

return, until she starts getting ominous warnings from Wilf Netherton, who claims

to be from the future London she visited. It is a lot to swallow, but the hit

squad that comes after her is pretty convincing. Fortunately, Burton and his

veteran drinking buddies can protect her and their ailing mother in the short

term, but she will have to work with Netherton in her future peripheral to

figure out who is trying to kill them and why.

The

broad strokes of Peripheral might sound like cyberpunk in a familiar Matrix/World on a Wire kind of vein, but the details are very different. For one thing,

there is sort of a time travel element. It is also weirdly timely, because the

Russian oligarchs (“the Klept”) are one of the major factions vying for

dominance in future London. That might be somewhat less likely now, after they were

targeted with sanctions for supporting Putin’s war in Ukraine, but it was

pretty darned insightful when Gibson’s novel was published in 2014.

The

future London Fisher visits also looks really cool, in a way that is not a

carbon copy of previous Blade Runner-esque dystopian mega-cities. Smith

and the rest of the writing staff also depict Burton Fisher and his fellow

veterans with unusual sensitivity and empathy, particularly Conner Penske, a

triple amputee, who is still a formidable foe to fight. Understandably, the

potential of peripherals will hold interest for him.

Still,

the foundation of the series is the central sibling relationship, which Chloe

Grace Moretz and Jack Reynor develop quite compellingly. They truly could pass

for siblings and both convincingly sound and carry themselves like natives of

border state hill country. Neither is a dumb hillbilly—quite the contrary, but

they are definitely the products of their hardscrabble environment.

Moretz

has immediate sibling rapport with Reynor, but she develops some intriguingly ambiguous,

potentially romantic chemistry with Gary Carr’s Netherton over the course of

the first six episodes (out of eight) provided for review. Carr definitely

follows in the tradition of hardboiled dystopian anti-heroes (starting with

Lemme Caution in Alphaville), but his Dickensian backstory adds a lot of

complexity to the character, while illuminating the social divisions of future

London.

More people were killed in Roger Spottiswoode’s 1980 train-bound slasher

movie than during Runaway Train, Silver Streak, or Murder on the

Orient Express (but probably not Train to Busan). It was supposed to

be a party train, but a mystery man in a Halloween mask crashed it hard. There

will be another killer party in Philippe Gagnon’s remake of Terror Train,

which premieres tomorrow on Tubi (following its screening at this year’s

Brooklyn Horror Film Festival).

Alana

reluctantly agreed to participate in a really mean hazing prank, but she had no

idea “Doc,” the fraternity president, would use a real cadaver. The shock sent

the poor-pledge victim to the mental ward. She was appalled, but he blackmailed

her to keep silent. Awkwardly, her boyfriend Mo remained in the frat, so there she

is, rubbing shoulders with Doc at the first party hosted by more sensitive successor.

You

can kind of understand why she accepted the invitation, since it will be a

costume party, with a hip, “edgy” magician performing. Unfortunately, there

will be an uninvited guest, wielding a sharp knife. This time, our killer

passes unnoticed wearing an evil clown disguise, instead of the original’s

Groucho Marx mask (which a lot of Millennials presumably wouldn’t recognize).

Soon, the psychopath is carving up partiers, but everyone is too busy drinking

or watching the entertainment to notice.

Screenwriters

Ian Carpenter and Aaron Martin ditched the original’s shocking twist, which

comes as no surprise, if you remember what happened. Arguably, the remake might

also be somewhat gorier. However, in many other respects, it remains

surprisingly faithful to the 1980 film. Most importantly, the enigmatic

magician still plays an important role keeping viewers off balance. To this day,

it remains David Copperfield’s only true dramatic role, but he was amazingly

weird and he had real deal magic chops.

Tim

Rozon is shockingly great assuming his role and his cape. Once again, his

unnamed magician character really elevates the remake above standard slasher

fare. Of course, he is flamboyantly over-the-top when chewing the scenery and

performing his illusions. That is the whole point.

If the UK hadn’t banned fox hunting, it might have saved these working-class

thieves a lot of trouble. Naturally, these upper crust hunters turn to hunting

people as a way to keep their traditions alive. That might sound extreme, but

the Manhattan DA wouldn’t even prosecute them for it, as long as they kept

their hunt to the subway platform, forcing them down to the level of tacky proletariat

killers. Indeed, the hunters find there is a lot of fight in their prey during the

course of Tommy Boulding’s Hunted (a.k.a. Hounded, a more

descriptive title), which opens tomorrow in Los Angeles.

Leon

thought he was done burgling high-class estates after raising enough money for

his brother Chaz’s uni tuition, but he agrees to one more job. They were

supposed to pilfer a ceremonial hunting knife, but it was a set-up. Suddenly,

they wake up in a field with a pack of hounds baying after them. Katherine Redwick,

her distinguished father Remington, and her hot-blooded brother Hugo intend to introduce

her twit nephew Mallory to the hunt, using them as a substitute for the fox.

It

seems like just illegally hunting foxes would be easier and cheaper to cover-up

than hunting people, but apparently this is a long-standing Redwick tradition.

It keeps the uppity lower classes in their place, as the loaded,

class-conscious dialogue makes ridiculously obvious. Listening to the Redwicks

will make any reasonably grounded viewer roll their eyes, but the rest of the

film is competently executed. It just lacks style, originality, and

inspiration. Frankly, it deserves a non-descript title like Hunted.

There is no question Captain Pat Hendry and his fellow Air Force officers did

a much better job defending Earth in the original Thing from Another World than

Kurt Russell did in John Carpenter’s remake. These young Inuit girls are cut

more from Hendry’s cloth, because they are hunters. Unfortunately, so is the alien

parasite threatening their community in Nyla Innuksuk’s Slash/Back,

which screened at the 2022 Brooklyn Horror Film Festival.

Maika

and her friends either resent their depressed Nunavut community (like her) or

they are resigned to it (like her best friend Uki). Fortunately, it is the sort

of town that hardly notices a teen like her carrying a hunting rifle down the

street, because she is going to need it.

The

first victim was an American scientist, but the “thing” had to possess and

consume polar bears, until the girls stumbled across it path. Maika manages to

save her tag-along sister from a hive-mind-controlled bear, but the aliens will

follow the scent of its blood back to the community.

For

everyone who thought the ulu was under-utilized in the fight against alien

invaders, Innuksuk and co-screenwriter Ryan Cavan finally come through with the

goods. In this case, the invaded bodies are not the insidious pod people

infiltrating home and hearth, as in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Instead,

the parasite turns their blood black and their skin starts to sag and get generally

nasty looking. One possessed host even resembles Leatherface.

The

makeup and practical effects are entertainingly gory, in the right kind of way.

Admittedly, the initial rampaging polar bear looks kind of weird and unnatural,

but that makes sense in the full context of the film. It takes a bit of time

for it to get going, but Slash/Back turns into a satisfying

alien-hunting movie.

VHS won its format war in 1980 and it remained the dominant media until DVDs

finally started outselling tapes in 2002. Frankly, it probably had a better run

than DVDs, which have already become an old fogey medium. That means people were

definitely still using VHS in 1999, right around the time of Y2K. It is a

fitting time for horror, but the found footage is a bit spotty this time around

in V/H/S/99, which premieres tomorrow on Shudder, after screening at the

2022 Brooklyn Horror Film Festival.

Sometimes

the punk rock attitude is its own worst enemy, as is true for the awful teen

garage band, in “Shredding,” written and directed by Maggie Levin. They hatch a

scheme to jam and essentially desecrate the site where a promising punk band

(sort of like the Go-Go’s before they went pop) was trampled to death by their

own fans. This is a bad idea for the characters and nothing new in terms of

film.

Johannes

Roberts’ “Suicide Bid” is a vast improvement. The title refers to freshmen who

only apply to a single Greek house. In this case, the sisters of a particularly

nasty sorority haze poor Lily by forcing her to spend the night sealed in a

coffin. You would think they had learned their lesson, since there is a creepy

campus legend about the vengeful spirit of a pledge the sisters hazed to death several

years ago. Regardless, Roberts quite cleverly combines the confined-space

horror of Buried with good old fashioned supernatural horror.

Sadly,

it is followed by the nearly unwatchable “Ozzy’s Dungeon,” from Flying Lotus,

who previously helmed visual assault that was Kuso. This mean-spirited segment

drags on interminably, even turning sympathetic characters into creepy psychopaths.

Weirdly (and unintentionally) the sleazy host of a rigged Nickelodeon-style

game show for kids becomes the most interesting character, as the “victim” of

the deranged mother, whose daughter was permanently disfigured while appearing

on the show. This is just a complete misfire.

Given

how bad “Dungeon” is, Tyler McIntyre’s “The Gawkers” inevitably represents a

big step up in quality. It is a fairly straightforward yarn wherein voyeurism

is violently punished. It is very similar in tone to the “Amateur Night”

segment in the original V/H/S, but the girl the teen boys lust after is

never fleshed out to any extent, unlike “Lily the Demon,” who got her own

movie, SiREN.

By

far, Vanessa & Joseph Winter’s “To Hell and Back” is the best of the ’99 edition.

The Millennium is about to turn, which makes it the perfect time for a satanic cult

to summon its patron demon. Nate and Troy are there to record it for reality

TV, because that kind of thing seemed like a good idea in 1999. However, when a

minor demon crashes the party, they are both inadvertently swept up in its

banishment back to Hell.

This

might just be the most convincing depiction of Hell (or whatever) since Jigoku.

Yet, the Winters also milk the situation for [pitch-black] humor. Archelaus

Crisanto and Joseph Winter are terrific bickering and freaking out as the

reality TV sad sacks. Plus, Melanie Stone is a showstopper as the demon Mabel.