In its 1960s prime, Hammer Films did gothic horror better than anyone. However,

for their most successful TV series, they leaned into folk horror. Even in

episodes that do not rely on traditional folk horror tropes, bad things tend to

happen to anyone who visits the countryside. Hammer had co-produced a

Frankenstein pilot that failed to sell as well as a previous anthology series

that came and went, but in 1980 they scored a hit with genre fans when Roy

Skeggs created Hammer House of Horror, which airs today as a Halloween

binge on Decades TV (hang on, this will be a long one).

Rather

fortuitously, the series starts with probably its best episode, “Witching Hour”

(directed by Don Leaver and written by Anthony Read), wherein viewers quickly

get a taste of the series’ blend of the sinister and the sexual. Film composer

David Winter rightly suspects his actress wife Mary is having an affair (as we

see with absolute certainty), but Winter has no idea she is in fact sleeping with

his best friend.

Unfortunately,

Winter’s jealousy and resentment leaves him vulnerable to the attacks of

Lucinda Jessup, a 17th Century witch, who transported herself across

time to avoid a date with the stake. Ironically, it will be his estranged wife

who tries to save Winter from her sexual and spiritual domination. Jon Finch

(star of Hitchcock’s Frenzy, who turned down an offer to play James Bond)

is a spectacular mess as Winter. Prunella Gee (the nurse in the rogue Bond

movie Never Say Never Again) is terrific, but underappreciated by horror

critics for her forcefulness as his wife (probably because of her sex scene),

while Patricia Quinn chews the scenery like a world champion as Jessup. The folk

horror is pronounced and pretty scary.

In

contrast, “The Thirteenth Reunion” (directed by Peter Sasdy and written Jeremy

Burnham) is more darkly ironic than outright frightening. Yet, it is interesting

in its way, because it serves up some rather mordant cultural commentary. The

strange business involves a reporter infiltrating a trendy but abusive New Age

weight loss clinic—definitely shades of EST here. There is also an appealing

budding romance between her and another patient, because neither are typical

romantic leads, but it is rudely interrupted.

While

“Reunion” is a product of its day, “Rude Awakening” (directed by Sasdy and

written by Gerald Savory) feels somewhat ahead of its time, because of its

circular structure. Norman Shenley is an estate agent who keeps waking up from

dreams in which he is repeatedly punished for a crime he has not [yet] committed—the

murder of his wife. Resolving to get to the bottom of things, he keeps driving

back out to the creepy old manor of his nightmare, only to befall another gruesome

fate, before waking up again.

This

episode really doesn’t seem fair, because it almost amounts to cosmic

entrapment. However, the variations of each successive go-round are quite compelling

and Denholm Elliott is perfect as the luckless Shenley.

“Growing

Pains” is an underwhelming evil kid-ghost story and “Charlie Boy” we’ll skip

because its too apt to become cancelation bait. “The House that Bled Death”

(directed by Tom Clegg and written by David Lloyd) is not perfect television

either but it became notorious in the UK for a scene of blood showering down

from the ceiling on a child’s birthday party. It turns out the house a young

family bought at a bargain price really wasn’t such a good deal after all. This

episode appears to be inspired by the Enfield Poltergeist that was also the

subject of The Conjuring 2. The Hammer take is very different, until

suddenly it isn’t.

Probably

the most viewed episode is “The Silent Scream” (directed by Alan Gibson and

written by Francis Essex), because it stars long-time Hammer favorite Peter

Cushing. Martin Blueck looks like a kindly old man, but he is really a National

Socialist war criminal (masquerading as a camp survivor), who befriends

down-on-their-luck ex-cons like Chuck to lure them into his cruel Skinner-esque

behavioral experiments.

“Scream”

is easily the darkest, bleakest episode of the anthology. Cushing’s knack for shifting

from kindly to malevolent at the drop of a hat serves the story quite well. The

working-class pathos Brian Cox brings as Chuck heightens the episode’s claustrophobic

discomfort. It is creepy, but a real downer.

A

couple gets stranded on a country road in “Children of the Full Moon” (directed

by Clegg and written by Murray Smith), as they often do in Hammer House.

The reference to a full moon is not accidental, but the payoff monster fans expect

comes very late in the episode. Mostly, it is about more creepy kids and a

creepy old lady.

Most British TV detectives are usually DI’s or DCI’s (Morse, Lewis, Lynley,

Frost, Banks), but P.D. James’ signature eventually rose to the advanced rank

of Commander. He was also a published poet, with a tragic backstory, so he well

understood the dark places of the human soul. Most importantly, Adam Dalgliesh

was unfailingly professional and competent. The no-nonsense detective was a

war-horse anchor for ITV (and then the BBC) in the UK and PBS’s Mystery in

America, so it is not surprising to see him get a fresh new series treatment in

Dalgliesh, which premieres Monday on Acorn TV.

In

series’ first two-part case, “Shroud for a Nightingale,” DCI Dalgliesh is less

than impressed with his new DS, the crass Charles Masterson. He does not take

to Dalgliesh either, but he is somewhat intimidated by the detective’s

commanding bearing. Still mourning his wife and unborn child, Dalgliesh is

assigned the case of a poisoning in a nursing college, because of its sensitive

nature. The school has powerful patrons and is expecting a high-profile visit.

Tragically, there will be further murders, to cover the killer’s tracks.

The

second two-parter, “The Black Tower” represents an improvement, because of the

remote but visually striking location and it also gives us a break from the

Dalgliesh/Masterson dynamic, which gets a bit tiresome. Dalgliesh arrives to

visit an old friend in priestly orders, who is on staff at a provincial home for

disabled residents, only to find he passed away a few days prior. That is just

what Dalgliesh needs, more grief. However, he soon starts to suspect his friend

was murdered, especially when more bodies start piling up.

Steven

Mackintosh makes a worthy suspect and foil as Wilfred Antsey, the arrogant

director of the almost cloistered home. He provides the sort of sparring

partner “Nightingale” lacks. Although the local police chief is too lazy to

mount a serious investigation, Dalgliesh finds an ally in Constable Kate

Mishkin. In terms of themes, this could be the episode of Dalgliesh that

hardcore fans of the original adaptations most appreciate.

The

initial reboot season concludes with “A Taste for Death,” which auspiciously

starts in a church. Inside, a disgraced politician and a local homeless man

were sliced up, in a transparent effort to make it look like a struggle between

them. To help his team, Dalgliesh has transferred Mishkin from Bristol, not

exactly thrilling Masterson.

There

is some decent procedural stuff in “Taste,” and it is great to see distinctive

character actors like Jim Norton (seen on Broadway in The Mystery of Edwin Drood) and David Pearse pop up as Father Barnes and pathologist Miles

Kynastone, respectively. Patrick Regis is also quite a notable presence as

Gordon Halliwell, the loyal chauffeur of the deceased’s stonewalling mother.

Frankly,

the rivalry between Masterson and Mishkin (nicely played by Carlyss Peer) feels

flat and predictable, However, “Taste” really gives Bertie Carvel a chance to

shine as Dalgliesh during the emotionally heavy third act. Although Martin showed

a bit of feeling in his two Dalgliesh mysteries, Roy Marsden was always

scrupulously reserved and detached (that was what made Dalgliesh Dalgliesh).

Arguably, Carvel combines the best of both.

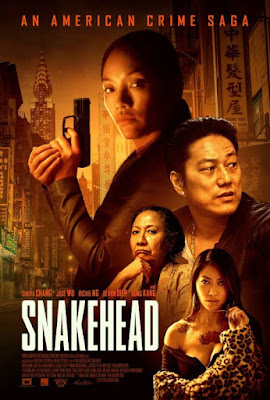

It only makes sense that a former Red Guard leader during the Cultural

Revolution could so easily segue into human trafficking. In both roles, human

beings were just masses to be exploited. The prosecution of her Chinatown syndicate

brought wider media attention to the practice of human smuggling and the term “Snakehead”

that described it. Her shrewd underworld domination inspired Evan Jackson Leung’s

Snakehead, which opens today in theaters and on-demand.

As

the woman who will become known as “Sister Tse” makes clear in her opening

narration, she is neither an economic migrant nor a political refugee. She came

to America, via Dai Mah’s trafficking network, for very personal reasons. To

find her daughter. Unfortunately, she must first pay-off a debt of over $50,000

to Dai Mah. Initially, the Sister Ping-analog figures she can simply be

consigned to a brothel, but Sister Tse is not so inclined. Impressed by her

toughness and resilience, the Snakehead boss starts giving her low-level tasks

in her criminal outfit.

Soon,

Sister Tse earns Dai Mah’s trust and confidence, but also the jealousy of her thuggish

son Rambo. His scheming girlfriend Sinh also has her claws out for Sister Tse. Plus,

through these new associations, she attracts the attention of the FBI. As a

result, each new high-priority assignment comes with considerably risk, but it

is hard for Sister Tse to pass up chances to slash her debt.

Leong,

who helmed the terrific doc Linsanity, brings a gritty street-level

perspective and New York attitude to this years-in-the-making passion project.

It is two-thirds crime thriller and one-third family tragedy, but the two parts

fit together cohesively. He mostly refrains from lecturing the audience on policy

issues, aside from an unflattering portrayal of a minutemen-style border patrol.

(You could even argue it discourages illegal immigration.)

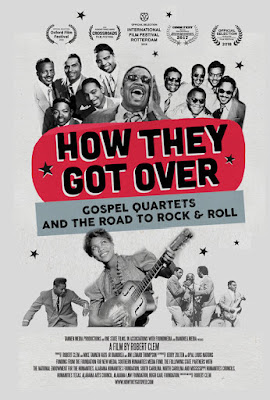

There would be no rock & roll without “Rock Me.” You could say that

satanic rock owes its existence to the Church. Indeed, Elvis Presley always

acknowledged Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s influence on his music. Tharpe was a

pretty big name already, even before he copied her act. Yet, it was the success

of those who came before her who made gospel music a viable career opportunity for

the musicians (primarily vocalists) whose oral history informs Robert Clem’s

documentary How They Got Over, which opens tomorrow in Los Angeles.

Unlike

other gospel docs (like Rejoice and Shout), Got Over does not go

all the way back to the roots of gospel and Thomas A. Dorsey. He basically

starts immediately post-war, when there were little job prospects for blacks in

the Jim Crow South. Life and entertainment almost entirely revolved around the Church,

where touring gospel artists might make gas money to the next town if they were

okay, but could build a following if they had talent.

Although

Clem covers Sister Rosetta and some of the women’s gospel ensembles, he deliberately focuses on the male harmony singers, who followed the lead of the original

Golden Gate Quartet. Among those groups, he largely spotlights the Dixie

Hummingbirds, thanks to original member Ira Tucker, whose commentary helps

drive the film. Probably, the next most prominent group would Clarence Fountain

and the Blind Boys of Alabama, which makes sense given their recognition beyond

the gospel world.

In the 1930s, Hollywood studios were reluctant to criticize the National

Socialist regime, out of fear their films would lose access to the German

market. Sound familiar? By the 1970s, Nazis were regular movie villains, but

there was still great interest in adapting Albert Speer’s spin-controlling memoir

Inside the Third Reich. Eventually, it became a two-part TV movie after

his death, but Paramount thoroughly kicked the tires of a prospective feature

film in the early 1970s. Vanessa Lapa contrasts Speer’s evasive recorded

conversations with spec-screenwriter Andrew Birkin against the tapes of his

Nuremberg tribunal in Speer Goes to Hollywood, which opens tomorrow at

Film Forum.

The

notion of Speer as the moderate National Socialist persists today, in large

measure due to his widely read book. An architect by training, Speer was

appointed Minister of Armaments, which entailed responsibility for the widespread

use of slave labor at munitions plants. Of course, he claimed he never fully

understood the horrific conditions workers endured. Based on the tapes, it

sounds like Birken (whose credits include The Name of the Rose, The Final

Conflict, and King David) gave him some benefit of the doubt, but

kept hoping to hear some genuine remorse from Speer.

The

thing is, we don’t really hear any of it, because much of the tapes had

degraded to such an extent, Lapa was forced to re-record the transcript, which

raises questions similar to those surrounding the Anthony Bourdain doc. The

tapes were thoroughly cataloged and documented, so the words themselves are

authentic, but there is maybe a degree of subjectivity in their presentation.

Yet,

the real problem with the film is its over-reliance on unimpeachable footage of

the Nuremberg Tribunal, which play out in long extracts. As a result, viewers

who have seen Stuart Schulberg’s historically significant Nuremberg: It’s Lessons for Today might understandably feel like there is a good deal of

redundancy Lapa’s film.

This rural French mountain village is worlds away from the Texas seen in Blood Simple or the Kentucky of The Devil All the Time, but its rural noir

dynamics are very similar. You might logically wonder how a tragedy there could

be related to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast. Eventually the truth will be

revealed, but director-screenwriter Dominik Moll will take his time teasing it

out through flashbacks and narratives games in Only the Animals, which

opens this Friday in New York.

Evelyne

Ducat disappeared on the way to her winter vacation home, but Alice Farange

does not understand how anyone she might know could be involved. She is also distracted

by her own issues. Lately, she has conducted a rather open affair with Joseph

Bonnefille, a rustic farmer, whom she met through her work at his insurance

company. Unfortunately, that relationship is also about to take a sour turn,

for reasons she does not understand.

Meanwhile,

things are still frosty with her husband Michel, who is acting especially

distracted lately. Regardless, she is still genuinely concerned when he returns

home late at night, bloodied and battered. She assumes they are fighting over

her, but what is really going on is much darker and more complicated—and it

will take a while for the full picture to reveal itself.

Only

the Animals

is definitely constructed like a puzzle box, in which clues are teased in full

sight, but viewers need Moll to keep rewinding the narrative, to provide the

context needed to put the pieces together. Fortunately, they all really do fit

together at the end. The truth will indeed be revealed, but before then, Moll

manages to wring a fair amount of suspense out of the mystery. There is also a

rather surreal left-turn taken during the third act, somewhat akin to Charles

Sturridge’s A Handful of Dust.

The recent boom of horror films from Southeast Asia makes sense, since

countries like Malaysia and Indonesia have Islamic, Shamanistic, and Animist

supernatural folkloric traditions to mine. It also helps when the local

governments ease up on censoring genre films. You could certainly say Malaysia

did so in this case, when they submitted an eerie tale of black magic for

consideration as a potential best international feature at last year’s Oscars. It

wasn’t nominated but it was still a moment for Malaysian horror. Screenwriter-director

Emir Ezwan’s ROH (a.k.a. Soul) also happens to be genuinely

scary, so it makes perfect Halloween viewing when it releases Friday on VOD.

For

some undisclosed reason, Mak moved with her young son Angah and daughter Along way

into the heart of the forest, a formidable distance from the nearest village.

The children eagerly await their absent father, but it is clear Mak never

expects to see him again. Everyone has a regular regime of chores just to get

by, but their routine is interrupted when a strange little girl follows the

children home.

Initially,

they assume she wandered away from the village, but her sinister behavior

suggests a more infernal nature. Just when they think her evil has passed, a

ruthless old hunter comes looking for her. Caught between a metaphorical rock

and a hard place, Mak’s family experiences curses and supernatural illness.

Perhaps providentially, an itinerant medicine woman offers advice, but she

vibes viewers the wrong way.

ROH

has

some of the gore Malaysian horror films are known for, but it is also darkly brooding

and suggestive. Ezwan masterfully creates an atmosphere of dread and

pestilence. It really is not accurate to describe the film as slow or

deliberately paced. Viewers are not sitting around waiting for things to

happen. Rather, we’re holding our breath and hoping things don’t happen.

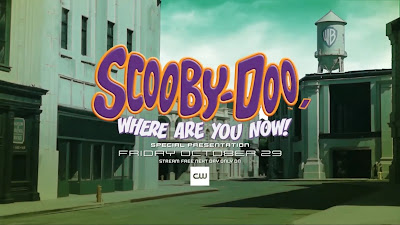

For 52 years, Scooby and Mystery Incorporated have been unmasking monsters.

If you haven’t kept up with their recent Cartoon Network series and straight-to-DVD

animated features, you might not realize they are as busy now as they ever

were. They haven’t aged a day in all that time—it must be those giant dagwood

sandwiches keeping Scooby and Shaggy youthful. There is a diet book somewhere

in that, but their next project is a reunion special. They never broke-up, but

reunion specials are hot, so Warners booked studio time for their

reminiscences. Yet, wouldn’t you know it, they end up with a haunted soundstage

in Scooby-Doo, Where are You Now?, a new hybrid animated-live-action special

premiering Friday on the CW.

A

gig is a gig for Mystery Incorporated, so they are happy to sit down with the

host and producer (both “real” people) in their old soundstage to discuss their

past cases. However, weird noises keep interrupting them. The Warner employees

did not want to admit it, but reportedly the studio is haunted. Recently, their

old nemesis the “Snow Ghost” has been scaring away productions, so they

naturally ask Mystery Incorporated to sleuth it out.

Even

by the standards of the early Saturday morning cartoons, this mystery is pretty

simple, but the “reunion” format facilitates some amusing self-referential

humor, including testimonials from the likes of Batman, Johnny Quest, Jabberjaw,

and the Power Puff Girls. There are also clips and soundbites from the

real-life voice-over artists, including Frank Welker, who has portrayed Fred

since the show’s inception and Scooby himself, for almost twenty years.

Horror can be a keenly effective vehicle for social commentary. The great

George Romero was a master of inserting his liberal perspective, without detracting

from the narrative. However, when didacticism gets in the way of the storytelling,

it is especially obvious in the horror genre. Such thoughts are prompted by this

week’s episode of Creepshow (featuring an inventive Romero homage),

which premieres this Thursday on Shudder.

Prepare

yourself for a lecture on the American healthcare system in “Drug Traffic”

(directed by Greg Nicotero and written by Mattie Do & Christopher Larsen). In

this case, the drug smuggling of the title refers to the life-saving

prescription drugs that are affordable in Canada, but prohibitively expensive

in the U.S. It is crusty border guard Beau’s job to keep them out. Before your

eyes roll out of your head, take comfort from the way crafty old Beau outsmarts

the opportunistic leftwing Congressman, who organized a patient caravan up to

Canada, with plenty of media to film it, of course, of course.

However,

unbeknownst to either Federal public servant, the Congressman’s party includes

a very sick young woman, whose mother hopes to forestall a rather macabre

transformation with a pharmaceutical cocktail. It is not much of a spoiler to

say this turns into a monster story—and it’s a cool one. Fan favorite Michael

Rooker is funny as heck as Border Patrolman Beau, while Reid Scott is

spectacularly cynical as the power-hungry Congressman. (The suggestion that

many politicians advocating greater socialized medicine don’t really believe in

it and are only following their polls earns a red “fact check: true” checkmark.)

Together, these characters and juicy performances largely deconstruct and

undermine the story’s ideological slant—and that’s a great thing.

“A

Dead Girl Named Sue” (directed by John Harrison and written by Heather Anne

Campbell, based on Craig Engler’s short story) is the second Creepshow story

that incorporates scenes from Romero’s conveniently in-public domain Nightof the Living Dead, following The Night of the Living Late Show. The

story unfolds on the same night as the fateful events in that farm house, in a

small town not so far away. Ironically, many of the good townsfolk want to take

advantage of the confusion to dispense some frontier justice on the corrupt

mayor’s sexual predator son, Cliven Ridgeway.

Back

in the station, Police Chief Evan Foster can see the news reports from the classic

movie playing on TV. He does not believe in lynch mobs, so he sets out to take

Ridgeway into protective custody. Yet, what he finds will test his principles.

Although

set concurrently, “Dead Girl Named Sue” is a fitting Living Dead story

for our violent year of 2021. At a time when so-called “bail reform” in cities

like New York has turned policing into a catch-and-release endeavor, we can

well relate to the frustration of Foster and his fellow townsmen. For those who

know the film intimately, it is also worth noting the town’s band of

prospective vigilantes is racially mixed. Such is the extent of the anger at

the town’s revolving door jail.

The fantasy genre is about as archetypal as fiction gets. Take for instance

the “sacred bloom,” a flower that imparts terrible, dreadful knowledge. Does

that bring anything to mind? Regardless, mankind cannot handle it, but an evil,

power-mad sorcerer is determined to acquire it in Philip Gelatt & Morgan

Galen King’s animated The Spine of Night, which opens this Friday in New

York.

Initially,

Ghal-Sur was a mortal scholar, who was probably only extraordinary for his

arrogance. As a result, he is quite put off by his assignment to record the

history of Lord Pyrantin, a budding tyrant, who naturally expects the scholar

to cater to his vanity. However, Ghal-Sur must protest when he witnesses

Pyrantin’s crimes against the nearby swamp people, who had a compact with his

scholars’ guild. Of course, that lands him in the dungeon with the shaman,

Tzod, who is the only survivor of her people. When he sees her employ the

healing power of the bloom, it literally creates a monster.

Over

the course of centuries, Tzod will fight to prevent Ghal-Sur (who has become an

inhuman conqueror in the tradition of the “God Emperor” of Dune)

from centralizing all of the supernaturally potent bloom under his own control.

In doing so, she will embark on an epic journey to the final surviving bloom, safeguarded

by “The Guardian,” who is not unlike the Knight in Indiana Jones and the

Last Crusade. However, Tzod is not the only one who has had enough of

Ghal-Sur’s’ oppression. A band of winged assassins, reminiscent of Prince

Vultan’s Hawkmen in Flash Gordon, have decided they might as well try to

take him out, or die trying.

Obviously,

there are tons of precedents for almost everything in Spine, but

honestly that is true of just about every epic fantasy. Frankly, fantasy fans

want to see all those classic elements. The point is to find distinctive ways

to repackage them, which Gelatt & King do by incorporating a hand-rotoscoped

style of animation that evokes the vibe of Ralph Bakshi’s vintage Tolkien films

and the original Heavy Metal. Like the latter, there is indeed a great

deal of unenticing nudity in Spine. It is also violent, but always in

service of the narrative. The Heavy Metal comparison is especially apt,

because the animation is not super-complex, but it is cool looking.

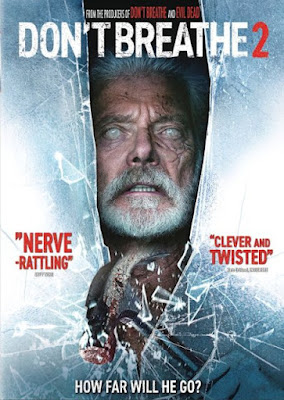

Supposedly, Detroit was coming back. Yet, in 2020 homicides still rose 19%, even

though total population fell below 640,000. On the other hand, one of Detroit’s

most famous cinematic citizens has found redemption in a sequel. In Don’t Breathe, veteran Norman Nordstrom did not take kindly to a band of home

invaders (and frankly, we can’t blame him for that). It also turned out he had

a few sinister secrets of his own. Since that time, he moved to another

abandoned Detroit house, where he raises his adopted daughter Phoenix. He will

fight to his last breath (so to speak) when a gang of organ traffickers comes

for her in Rodo Sayagues’ Don’t Breathe 2, which releases tomorrow on

DVD.

It

was annoyingly problematic that Fede Alvarez’s original Don’t Breathe made

a villain out of a blind Vietnam veteran. (Yes, but I’m sure the filmmakers

would be the first to say they “support the troops.”) As a result, the sequel

is redemption for the franchise, as well as Nordstrom (a.k.a. “The Blind Man”).

We do not immediately learn how Nordstrom came to adopt Phoenix, but we

eventually understand he found her at an opportune time. During the subsequent

years, he home-schooled her, including a rigorous survivalist curriculum. This

being Detroit, those lessons will come in handy.

From

time-to-time, Nordstrom allows Phoenix to visit the outside world with

Hernandez, a veteran landscaper, who purchases the plants he grows in his

greenhouse. She is sympathetic, but she cautions him against his excessive

over-protectiveness. Yet, Raylan’s creepy meth-headed gang starts stalking

Phoenix during one of her rare outings with Hernandez.

Frankly,

Don’t Breathe 2 is probably more brutally violent than its predecessor. While

it doesn’t exactly try to walk-back the most damning elements of the first

film, it is clear Sayagues and Alvarez (who co-wrote and produced) hope viewers

do not remember them. This Nordstrom is haunted and guilt-wracked by his past,

but he is definitely a good guy.

Stephen

Lang is just as hard-nosed reprising his role as Nordstrom, but this time he

plays a flesh-and-blood human being, with heavy emotions. He also seems more credible

in the action scenes, even though he is even greyer and more grizzled.

Unfortunately, the idea of what the bad guys are up to is scarier than the

workmanlike performances of Brendan Sexton III as Raylan and Fiona O’Shaughnessy

as his Lady Macbeth.

Telling the life-story of a horror movie villain is a tricky business, because

they always keep coming back from the dead—as long as their box-office grosses

hold up. Sometimes genre fans might even lose track of their sequels and

reboots. However, writer-directors Gabrielle Binkey & Anthony Uro give six

horror icons the biography treatment (both on-screen and behind-the-scenes) in Behind

the Monsters, which premieres this Wednesday on Shudder.

Logically,

the series front-loads its most topical monsters, starting with Michael Myers,

a.k.a. “The Shape,” who is currently appearing in the hit Halloween Kills.

Unlike many critics, the commentators Binkey & Uro assemble are quite

forgiving of the pre-Halloween 2018 sequels, especially Halloween H2O.

There were more of these than you might remember, thirteen total films

including the Rob Zombie reboots, which makes the Michael Myers episode about

fifteen minutes longer than the next two.

Frankly,

Myers just doesn’t lend himself to the sort of archetypal analysis that other

monsters do. (They might even over-think the significance of the character’s

billing in the credits as “The Shape.”) However, Halloween franchise

fans should dig seeing Nick Castle (the original “Shape,” who made masked cameo

appearances in 2018 and Kills) discussing his iconic role with James

Jude Courtney, the most recent Michael Myers.

Even

though it is shorter, the Candyman episode digs deeper into the

character’s folkloric roots and inspirations. The film was based on a Clive

Barker story (who is absent from the episode), but screenwriter-director

Bernard Rose radically re-conceived the bogeyman, making him a product of

Southern racism. Rose and the original star of the franchise, Tony Todd, speak

at length about the character’s development. Plus, his original co-star, Virginia

Madsen, and reboot/sequel director Nia DaCosta add their perspectives. However, everyone

is sure to miss Baywatch’s Donna D’Errico, who appeared in the

straight-to-DVD Candyman: Day of the Dead, right?

Chucky, who just

launched a new USA TV series, is a one-named phenomenon, sort of like Madonna

and Liberace. In his previous, human-life, he was serial killer Charles Lee

Ray, before he supernaturally transferred his consciousness into a 1980’s-style

“Good Guy” doll in Tom Holland’s Child’s Play. This episode features

some of the best behind-the-scenes stuff, because the Chucky puppetry really

was cool, particularly for its time. We also hear from the great Brad Dourif,

whose voice work truly brought the character to life.

There was a time when just about everyone worked with at least one veteran on

their offices or factories. Often, there would be considerably more than one.

This was even still true during the years following the Vietnam War, but the

shift to an all-volunteer military also led to an unanticipated social and

cultural divide. Bridging the gap between veterans and civilians is clearly one

of the missions of the four-part American Veteran, which begins this

Tuesday on PBS.

Each

episode corresponds to a period of service, hosted (via off-camera narration)

by prominent veterans. Although there is supplemental historical context going

back to the Revolutionary War, the primary focus falls on veterans of WWII through

Iraq and Afghanistan. Perhaps the best episode is “The Crossing,” hosted by Marine

Corp vet Drew Carey, because it explains the basic training experience, which civvies

probably only know from films, like An Officer and a Gentleman. Although

Carey served during peace-times, he credits his tenure with making him at his

subsequent show business career.

Sen.

Tammy Duckworth hosts “The Mission,” which explores the dangers of deployment,

both physical and mental. She certainly has the standing to do so, since she

was seriously wounded during an RPG attack by Iraqi insurgents. However, it

would have been nice to also hear from a GOP veteran like Rep. Dan Crenshaw at

some point during the series, even though there is little in her commentary that

is overtly political. Regardless, the undeniable emotional crescendo of the

episode comes from a WWII Coast Guard veteran, who tearfully recounts his D-Day

experience shuttling troops to the carnage on the beaches on an amphibian landing

craft.

“The

Return,” hosted by actor Wes Studi, examines the challenges of homecoming. We

hear a great deal about recent veterans’ struggles with PTSD, but to the credit

of writers Stephen Ives and Gene Tempest, this installment also acknowledges the

scorn and hostility directed at returning Vietnam veterans by New Left activists.

At

some times, it seems like American Veterans compulsively airs out the

American military’s dirty laundry, especially when it comes to sexual assault and

past discrimination. This is particularly true of the final episode, “The

Reckoning,” which generally observes the lingering influence of military

service on veterans as the chart their post-service lives. J.R. Martinez is a

fitting choice to host, since he has built a successful career as an actor and

motivational speaker that he probably never expected when serious burn injuries

ended his Army service. However, “The Reckoning” also gives the U.S. military

credit for being ahead of society in some of its efforts, as when it racially

integrated in 1948.

This must be an alternate universe, because in this reality we still have

troops stationed in Afghanistan. Unfortunately for them, they are about to

encounter something even more dangerous than al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Our

over-the-horizon capabilities won’t make much difference either, because the

strange alien force is bent on complete planetary domination. People from

different walks of life in several different countries respond to the global

crisis in co-creators Simon Kinberg & David Weil’s Invasion, which

premieres today on Apple TV+.

This

is Sheriff John Bell Tyson’s last day wearing the badge, but something just doesn’t

feel right to him. Maybe it will be explained by the final call he responds to.

Also in America, Aneesha Malik, looks after her children as best she can, even

though she just discovered her husband has been unfaithful to her. That would

be the same husband whom she sacrificed her medical career to marry.

Meanwhile,

Mitsuki Yamato prepares the last technical checks for a historic manned Japanese

space flight. She is especially diligent, because Captain Murai is her secret

lover. Over in England, Casper Morrow (who suffers from unexplained seizures)

is about to leave on a school field trip, with his crush, Jamila Huston, and

his primary bully. Finally, in Afghanistan, we meet Trevante Ward, a U.S.

Special Forces Operator, who devotedly looks after his own men in the field to

compensate for a family tragedy back home.

Then

all heck breaks lose, but Kinberg & Weil never really give us a

comprehensive overview of the interplanetary struggle. Instead, they give us

fractured perspectives, such as that of the English schoolchildren, whose bus

is trapped in crater. Obviously, Invasion would not exist without War

of the Worlds and its many film and TV adaptations. In a way, it tries to

combine the average-Joe POV of Spielberg’s disappointing War of the Worlds

and the scientifically trained perspective of Dr. Clayton Forrester in the classic

George Pal-produced War of the Worlds. Just as Pal’s film is vastly

superior to Spielberg’s, the sequences featuring Yamato and Ward are much more

interesting than those featuring the kids and the Malik family. As for the good

Sheriff, you might just forget he was in this show after the first episode.

These

inconsistencies are exacerbated by the slow pacing of the early episodes. Honestly,

they should reach the point of the sixth or seventh installments by the end of

the third. It basically takes a full episode for the Maliks to get from their

house to their car—and its just parked in their driveway.

However,

the cast is quite strong and in many cases very distinguished. The great Golshifteh

Farahani (who has been banned from her native Iran since 2009) is terrific as

Malik, even though she is stuck in the show’s most melodramatic story-arc. Yet,

Shamier Anderson truly drives the series, even more than her, with his riveting

performance as Ward.

Shiori

Kutsuna is credible and compelling as the highly intelligent but socially

awkward Yamato. She also probably has some of the show’s most poignant scenes

opposite Rinko Kikuchi and Togo Igawa, who are both memorable and engaging as

Murai and her slightly estranged father. There are also a bunch of kids in this

show, the best of which is probably India Brown as down-to-earth Huston. She is

very good, but viewers will quickly tire of the Lord of the Flies business

that traps her character. (And of course, Kiwi Sam Nail plays yet another

Oklahoma sheriff.)

There were several entertaining science fiction films produced by the East

German studio DEFA (like Eolomea and In the Dust of the Stars).

This isn’t one of them, but it would like to be. Jim Finn lovingly satirizes or

idolizes Soviet era futurism with a fictional mission to the moons of Ganymede

and Titan. They never make it. Instead, the two lost crews end up somewhere in outer-space,

where experimental film, kitschy fetishism, and the DIY impulse intersect in

Finn’s Interkosmos, which premieres Monday on OVID.tv.

There

really was an Interkosmos agency that was tasked with facilitating

collaborations between the Soviet space program and those of their socialist

allies (a.k.a. Captive Nations), as well as non-aligned nations receptive to

Soviet overtures. That is why the Indian Cosmonaut with the call-sign “Seagull”

was allowed to apply for the mission. As luck would have it, she is paired-up

with “Falcon,” a friend from her Russian studies, with whom she shares some

ambiguous romantic connection.

Finn’s

screenplay is less of a conventional narrative and more like a treatment that

establishes the back-story and alternate history of the failed mission to

colonize the Galilean Moons. In fact, much of his intra-agency details are

archly amusingly for old school Cold War observers. His hand-crafted sets and

props also have their grungy charm. In many ways, Finn’s Interkosmos plays

like a much smarter version of Tom Sachs’ A Space Program, which it also

predated by about ten years.

Unfortunately,

Finn sometimes gives us too much of his idiosyncratic vision. There are several

long, drawn-out monotone lectures on the supposed superiority of socialism over

capitalism (and freedom) that might (or might not) be intended as satire but

eventually become punishment. Interkosmos is the first of Finn’s

so-called “Communist Trilogy” that concluded with The Juche Idea. Both

clearly engage with the images of propaganda, but Interkosmos is much

more ambiguous in its presentation.

In horror movies (and TV) time will always catch up with your stupid butt. No matter

what you do, that bell tolls for you. This week, one character tries to cheat

time and another looks forward to what might be preserved in a time capsule,

but in this genre, everything comes to a bad end. Frankly, the first story is a

bit more Twilight Zone-ish and the other is animated, but it is still all

the same difference when the latest episode of Creepshow premieres

tomorrow on Shudder.

That

wardrobe in “Time Out” (directed by Jeffrey F. January and written by

Barrington Smith & Paul Seetachit) is not just a family heirloom. It offers

a time-out from the passage of time, as Tim learns, when he inherits it from his

grandmother. That means he can pop in on the morning of a law school exam and study

for hours (or even days). However, even though time stops in the outside world,

he still ages inside. Her final note to Tim cautions against using it too much.

She also emphasizes he must always keep the key with him when he goes inside,

but seriously, what could go wrong?

Smith

& Seetachit’s premise is interesting, like the inverse-opposite of Adam

Sandler’s Click, including the fact that it is entertaining. It isn’t

really horror, but it definitely follows in the tradition of tragically ironic

anthology stories, such as Twilight Zone’s classic “Time Enough at Last.”

“Time Out” is a bit of a series ringer, but it is cleverly conceived and

well-executed, so genre fans should definitely appreciate its merits.

In

contrast, you can’t get much more Creepshow than “The Things in Oakwood’s

Past” (directed by Greg Nicotero & Dave Newberg, written by Daniel Kraus

& Nicotero, with Enol & Luis Junquera credited as animation directors).

That’s right, this one is animated, in an entertainingly colorful Creepshow/EC

Comics style. Mac Kamen is a human-interest reporter who has come to Oakwood to

do a story on the opening of a time capsule discovered by town librarian Marnie

Wrightson (presumably a hat-tip to artist Bernie Wrightson).

Wrightson

hopes it might hold answers the town’s great mystery. Like Roanoke, the entire population

of Oakwood disappeared two hundred years ago. Eventually, the town was

re-colonized, but nobody ever figured out what happened.

It debuted four years after Lost, but it predated Manifest, La Brea, The

Returned (both French and English versions) and most of the other series in

the where-the-heck-are-we-where-the-Hell-have-you-been-did-you-miss-me-while-we-were-gone

genre, by several years. It lasted four seasons and lent itself well to

distinctive title graphics, so it makes sense Rene Echevarria & Scott Peters’

science fiction franchise would get a new treatment—and here it is. The pilot

episode of Anna Fricke & Ariana Jackson’s rebooted The 4400 premieres

this coming Monday on the CW.

One

moment Shanice is driving to work and the next thing she knows, she is falling

from the sky, landing in a Detroit park with several hundred other people. It

is sixteen years later, but she doesn’t know that yet. Apparently, many of her

fellow drop-ins came from further in the past and at least one influencer came

from about 2015. She will find her followers and likes are down drastically.

The

super-helpful Federal government collects them in a downtown hotel and bring a

local probation officer and a bleeding-heart social worker to conduct

interviews. This really doesn’t make sense, especially considering how

psychologists must be on staff at the DOD, VA, and DOJ, even if the P.O.’s lover is

the FBI agent in charge. However, it turns out Jharrrel Mateo, the social

worker, has a personal reason for taking the case. He also quickly proves to be

slightly less than vigilant when Shanice escapes, thanks to the help of

teenaged Mildred, who suddenly exhibits telekinetic abilities. She is not the

only one with strange new powers.

They have something like Ouija boards in Japan too, but traditionally they

invoke trickster animal spirits, sort of like Coyote in the American Southwest.

It is still a bad idea to mess around with one, especially if you have offended

the local fox spirit. Somehow, a group of women on retreat manage to do exactly

that in Masaya Kato’s Ouija Japan, which releases today on BluRay.

Karen

Fujimoto is the expat wife of a Japanese businessman, who has trouble fitting

in with the neighborhood women. Akiyo Yoshihara, her “queen bee” boss at the

community center is always on her case, which sets the tone for the rest of the

women on staff. Her only friend is the caustic Satsuki Murakami, who works from

home (pre-pandemic) and is openly contemptuous of the other cliquey gossips. Much

to Fujimoto’s relief, Murakami also agrees to attend the center’s retreat, even

though it is hard to imagine her singing kumbaya or trusting anyone to catch

her if she falls backward. Fortunately, it turns out they will have activities

she is much better suited for.

Bizarrely,

Yoshihara uses a coin from the local shrine’s collection box for her game of

Kokkuri-san (or Ouija). This angers the already ticked off kitsune, who

magically installs a killer app on their phones that plunges them into a Battle

Royale-style game of kill or be killed. Like Highlander, there can

be only one at the end and if the deaths to not come with sufficient frequency,

the Fox Spirit will select someone at random. Inevitably, Fujimoto and Murakami

team up to take on the other alliances, even though they will eventually have

to turn on each other, if they survive that long.

Honestly,

Ouija Japan is the weirdest conglomeration of genre elements that really

don’t belong together, obviously including Ouija movies, Battle Royale, and cell-phone horror from the likes of Countdown. It

manages to cram them into a relatively economical 78-minutes, so at least that’s

something. This is definitely a cheap looking film with badly dubbed English

dialogue that often sounds like it was delivered phonetically. Yet, its

grunginess almost becomes a source of charm.

It was supposed to be the grand debut of South African thesp Edana Romney,

but it is now more remembered as the first films of Sir Christopher Lee and future

James Bond franchise director Terence Young. For Lee, it now seems like a reasonably

appropriate and not completely inauspicious debut, as a somewhat gothic, Daphne

Du Maurier-like psychological thriller (with scenes in a wax museum and a

masquerade ball). It was also a film about an artist’s obsession with beauty,

so it had to look good. Young’s strikingly lush black-and-white Corridor of

Mirrors gets a shiny new digital restoration, which releases tomorrow on

BluRay, from Cohen Media.

We

know from the in media res prologue, this story will end in tears. When the

flashback commences, fans do not have to wait long to see Lee, because he is part

of the aimless smart-set the beautiful and eligible Mifawny Conway whiles away

her nights with in London’s fashionable clubs, along with Lois Maxwell (who would

be forever known as Miss Moneypenny in the Bond films). Reportedly, Young has

to lend Lee his dinner jacket for the scene. Apparently Conway is a bit bored

with the old gang, because when legendarily ill-tempered artist Paul Mangin

walks in, she is quite struck by his Byronic figure.

Soon,

she is visiting him in his luxurious but old-fashioned mansion (mostly candle-light

rather than gaslight), where he dresses her in his exquisitely rendered

historical costumes, complete with matching jewelry sets. It is like she is his

personal doll to dress up as he pleases. To some extent, they are also lovers,

but their relationship is really one of uncomfortable control and submission.

Eventually,

Mangin admits he believes they are the recreation of Renaissance era lovers,

whose faithless relationship terminated in violence. Indeed, she is the spiting

image of the portrait that fuels his obsession, which sufficiently freaks out

Conway to rouse her from her trance-like state.

Visually,

Corridor is a dazzler. Imagine the thematically similar Vertigo (which

it predates by ten years), as directed by Cecil Beaton. The technical artistry

is remarkable, starting with Mangin’s Escher house, which does indeed include then

titular corridor (the mirrored doors conceal closets, holding outfits on one side,

with the matching jewels opposite). Somehow, it is also larger enough to house

a costumed bacchanal that looks like it could have been cut from Orson Welles’ Merchant

of Venice.

Andre

Thomas’s glorious cinematography is like a dark, gossamer dream, while the

richly romantic soundtrack builds on motifs from “Black was the Color of My

True Love’s Hair” and “These Foolish Things” (also heard in a weirdly operatic

rendition during the nightclub scene). The sets, dressings, and costumes are

some of the finest ever captured on film. The technical artistry is fabulous,

but Romney’s screenplay, co-written with her filmmaking partner Rudolph Cartier

is definitely a hodge-podge of lurid melodramatic elements, but they predate

plenty of classic films, such as Vertigo, Dead Again, and just barely Portrait

of Jennie.

For fans of Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, it is chance to see her old pal

Vincent Price in a new context. If MST3K is more your thing, Gypsy’s

beloved Richard Basehart was one of the regular stars. If neither appeals to

you, chances are you might be a bit befuddled by one of the weirdest episodes

of dramatic TV ever produced. Vincent Price and his evil little friends try to

take down the crew of the Seaview in “The Deadly Dolls” episode of Irwin Allen’s

Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (written by Charles Bennett and directed

by Harry Harris), which airs this coming Saturday night on ME TV.

While

docking for supplies, the charming Professor Multiple performs a puppet show

for the Seaview, gently lampooning the submarine’s officers. It is a great hit,

but oddly, his marionettes look inexplicably featureless after the show. That’s

because they will become doppelgangers for crew members, once Multiple starts

his body-snatching campaign. Eventually, even Admiral Harriman Nelson is

replaced by an especially nasty, smart-alecky puppet. Only Captain Lee B. Crane

(played by David Hedison, Price’s co-star in The Fly) remains free, shimmying

through airducts and crawlspaces (on a sub, mind you), like he is Bruce Willis

in Nakatomi Plaza.

It

is hard to describe how tripped out these devious little puppets are, like an

unholy union of Sid & Marty Krofft with Avenue Q. Honestly, they make

Vincent Price look reserved in comparison. You have to see it to believe it,

especially the puppet that looks like Basehart’s Nelson, who sort of sounds

like a megalomaniacal Alf (the sitcom alien).

Daniel Rye Ottosen was the last person to see hostage James Foley alive—the last

civilized person—who is still living and at liberty talk about it. Most of

their fellow hostages are confirmed murdered, but two remain missing. Ottosen

was the last to be released, thanks to his family’s desperate efforts. The true

story of Ottosen’s captivity is chronicled in Niels Arden Oplev & Anders W.

Berthelsen’s Held for Ransom, which is now playing in theaters and on

VOD.

For

the film treatment, Ottosen is simply known as Daniel Rye, which doesn’t sound

as Danish. Regardless, he is tremendously unlucky when he suffers a gymnastics-career

ending injury, because it indirectly sets him on the path of photojournalism. Rye

did not intend to cover the civil war when he arrived in Syria. Instead, he

hoped to document its impact on refugees living in a Syrian border city.

Unfortunately, his fixer was not aware the area had fallen under the control of

a Daesh (ISIS)-aligned militia.

First,

they accused Rye of spying for the CIA, but eventually realized his only value

to him was as potential ransom bait. On the advice of “Arthur,” their

mysterious ex-military hostage-negotiator, the Rye family tries to keep Daniel’s

abduction out of the media. As he explains, the ISIS hostage-takers prefer to

see themselves as holy warriors, so they do not appreciate having their violent

criminality called out. However, that will make it difficult for the average-Joe

Ryes to raise the two million Euros Daesh demands.

It

is a sad fact that Danish filmmakers are more interested in telling the stories

of Foley and his fellow hostages than Hollywood is, but such certainly seems to

be the case. Logically, Oplev and Berthelsen’s focus falls on Rye, a fellow

Dane, but they depict Foley with sensitivity and humanity. In fact, Foley

represents one of the best turns we’ve seen from Toby Kebbell since The Escape Artist. Anders Thomas Jensen’s adaptation of Puk Damsgaard Andersen’s

book also never waters down the sadistic torture Rye suffered at the hands of

Daesh, especially from the infamous “Jihadi John,” who appropriately comes

across in the film like a cheap, brutal thug.

Held

for Ransom

also makes much of the Danish government’s long-standing policy against

negotiating with terrorists. The film is unabashedly critical, but viewers who

can step back should understand the intent of the policy is to disincentivize

further hostage-taking. It is certainly hard on the Rye (Ottosen) family, but nobody

would want to see more families in their position.

The real villllains who made Wang Qiong’s family so miserable are never seen

in her debut documentary. That would be the Chinese Communist Party that

enacted and harshly enforced the notorious One Child Policy. The policy has

been somewhat loosened in recent years, but the trauma it caused Chinese society

will take generations to heal. Her family’s pain and guilt are as raw as ever,

as Wang intimately documents in All About My Sisters, which opens today

in New York.

Wang

has two sisters, the elder Wang Li and the younger Zhou Jin. Arguably, the

latter is lucky to be alive, but she doesn’t see it that way. Already having

two daughters, technically one over the limit, their parents first tried to

abort Zhou. When she was born anyway, they then abandoned her to her death,

before remorse drove them to reclaim her. Still hoping to eventually have a

son, they foisted her off on Wang’s aunt and uncle, whom Zhou assumed were her

parents throughout her early childhood.

Incidentally,

Wang’s other uncle was the village official primarily tasked with enforcing the

One Child policy, through scorched earth techniques. Eventually, Zhou learned

the truth of her origins, but she never really considered Wang’s parents to be

her parents—and they are all keenly aware of it. Indeed, they immediately fall

into their regular pattern of guilt-tripping and disapproving finger-wagging

whenever they are together. Often, Wang segues from documenter to documented,

as she tries mediate between Zhou and the rest of the family.

All

About My Sisters

so uncomfortably tragic, it is often nearly unbearable to watch. Yet, it is

hard to pass judgment against Wang’s parents for the mistakes they made,

because they were caught up in a rotten system, of the CCP’s perverse design.

Millions of infant girls were abandoned to their deaths and millions more were

aborted for reasons of gender selection. Wang’s parents were some of the few

who tried to undo some of the horrors, at least to some extent.

This adaptation of the late Lois Duncan’s YA novel really ought to be called “I

Know Who You Did Last Summer.” Maybe “Who Didn’t You Do?” would be more

accurate. In interviews, Duncan stated she was “appalled” by the violence of

the 1997 film version starring Jennifer Love Hewitt. It is hard to see how she

would like this one any better. Those teens, with their sex, drugs, and slasher

murders. However, she might be happy to see the notorious hook-wielding killer in

the sailor-slicker is absent from the first four episodes of Sara Goodman’s I

Know What You Did Last Summer, which premieres tomorrow on Amazon Prime.

Lennon

Grant’s friends are celebrating graduation with their usual hedonistic excess,

while she finds ways to do what she most enjoys—making her underachieving twin

sister Allison feel like dirt. It is all great fun, until she drives off with her

besties down a dark, lonely Hawaiian highway. Tragically, she hits someone

along the side of the road. In about the only plot point true to Duncan’s

novel, they opt to cover-up the incident rather than call the police.

A

year later, Grant is back from college in the lower 48 and rather trepidatious

about seeing the old gang again. However, someone is eager to see her. This person

unknown even left an ominous note—“I know what you did last summer”—scrawled across

the mirror in her room. When she tries to warn her friends, their first

reaction is denial and then to down-shift into panic when Grant’s stalker

starts murdering people.

Frankly,

he doesn’t murder enough people, quick enough. The Kevin Williamson-penned film

and its two sequels racked up a greater body-count than the first four episodes,

in less than half the time. They also came to reasonable resolutions. In contrast,

the series is conspicuously dragged-out with angsty padding. Goodman comes up

with a twist in the first episode that should be the source of some nifty

Hitchcockian suspense, but nothing that sophisticated ever gets going in the

episodes provided for review (the first four, out of eight total).

Nor

does it help that the focal characters are shallow, self-absorbed, and in most

cases morally gross. It almost makes us wonder if we are supposed to root for

the slasher. Arguably, the most interesting characters are Grant’s surfer

dude-turned responsible restaurant owner father and the chief of police, whom

he is sleeping with (nicely played by Bill Heck and Fiona Rene, the show’s

standout). Literally, everyone in this series is sleeping with someone—at least

one someone. By the rules of 1980s slashers, a lot of people need to die in

Goodman’s IKWYDLS, but she is way behind the pace.

The political assassination of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia rocked the government of Malta. Many politicians and their allies were

embroiled in the scandal, but to date, only the three thuggish assassins have

been prosecuted. However, divine retribution might be coming in the form of an

unusually virulent strain of malaria. British architect Alfred Rott might be lacking

in social graces, but he is sufficiently professional to see his latest job

through, despite the perilous outbreak in screenwriter-director Daniel Graham’s

The Grand Duke of Corsica, which releases tomorrow on VOD (and opens

theatrically in Brooklyn, just barely).

The

Grand Duke lives in Malta, rather than Corsica, in the decaying luxury you

might expect from a Thomas Mann novel. Rott originally came to the corrupt but

picturesque EU member-nation to build a concert hall, but he did not suffer

criticism gladly when the commissioning committee objected to his design’s

resemblance to female sex organs. However, that leaves Rott free to accept the

Grand Duke’s commission: his tomb.

Rott

is not sure what to make of his potential client, but as he enjoys the noble’s

hospitality, the architect starts to warm to his eccentricities and his

commission. Weirdly, we are not sure what to make of the rest of the film,

because Rott’s interactions with the Grand Duke are its most grounded scenes. Meanwhile,

more or less, an up-and-coming actor is filming a production about St. Francis

of Assisi, until the pandemic interrupts.

Unfortunately,

Corsica just doesn’t work as a film. Its deliberate artiness is rife

with pretention, but it lacks the grand deliriousness of a film like Lech Majewski’s

Valley of the Gods. However, it is not without its merits, primarily

those of Timothy Spall, who is compulsively watchable as the blunt-spoken Rott.

Wouldn’t you love to hear his character review this film? It would be brutal.

This is truly a Michael Myers film for the Biden years. The chaos we watched

unfold in the Kabul airport and the anarchy we try to ignore every day at the

border has come to Haddonfield. It is Halloween, 2018. Myers has survived

Laurie Strode’s death trap and is killing people with impunity. Sheriff Barker

is powerless to stop him and incapable of restoring law and order as the town

slips into panic and paranoid violence. Only those who previously survived

Myers’ prior attacks can hope to stop him now in David Gordon Green’s

Blumhouse-produced Halloween Kills, which opens Friday in theaters

nationwide.

The

action picks up immediately where Halloween 2018 left off. Strode is on

her way to the hospital, believing she finally put an end to Myers once and for

all. Unfortunately, at this time, he is actually hacking his way through the

firemen that were dispatched to the blaze consuming Strode compound.

This

being Halloween, a group of survivors from the original 1978 horror night have congregated

to commemorate those who died and toast those who saved them, including Tommy

Doyle and Lindsey Wallace, the kids Strode was babysitting, now all grown-up.

When word reaches them of Myers’ fresh killing spree, they decide to find him

and kill themselves. Obviously, it is easier said than done, but Doyle turns

out to be a good recruiter for vigilante patrols. Of course, Strode is convinced

he is coming for her, but her granddaughter isn’t so sure.

In

some ways, Halloween 2018 would have made a really satisfying conclusion

to the franchise, having retconned the other inferior sequels and reboots into

the stuff of fake news and urban legend. However, it probably was unrealistic

to think it would be so easy to kill off a bogeyman like Myers. Unfortunately, Halloween

Kills is conspicuously a middle film that obviously sets up the

already-announced third movie in the sequel trilogy, so there is not a heck a

lot of closure when the credits roll.

On

the other hand, Kill continues to echo the 1978 film in ways that deepen

the tragic resonance of the Michael Myers mythos. The return of his survivors is

more than just fan service (but it is that too, especially Kyle Richards reprising

her old role as Lindsey and Charles Cyphers making his first film appearance

since 2007 as Sheriff Leigh Brackett, now a security guard at the hospital—and they

are both quite good). Rather, their reappearance personifies the degree to which

the community remains traumatized by Myers’s crimes, even forty years later.

Jamie

Lee Curtis and Will Patton are both dependable as ever playing Strode and

Officer Hawkins, but since both are largely sidelined from the film due to

serious injuries suffered they in the previous film, a good deal of the load

falls on Anthony Michael Hall, who is really terrific as Doyle. It is a gritty

tormented performance that gives the film depth and a real edge.