The Paris Blues Club in Harlem is decidedly not named in honor of the 1961

Martin Ritt film. Even though that Sidney Poitier vehicle was all about jazz

musicians, it clearly suggested they could only attain true respectability

through proper classical music. As far as the musicians who play at Paris Blues

are concerned, you can stick that kind of respectability in your ear. They are

truly artists in their own right, but they still play to entertain the

neighborhood Harlem crowd—but until this fateful night, dancing was strictly

forbidden by New York’s archaic Cabaret Laws. Unfortunately, tragedy might come

with the joy of the law’s repeal in Christina Kallas’s Paris is in Harlem,

which screens as part of the (online) 2022 Slamdance Film Festival.

The

somewhat mysterious prologue suggests the night will come to an ominous end for

someone, but then Kallas rewinds, showing how nearly everyone had a very bad

day up to that point. Several happen to be professors (or more likely untenured

instructors) at a college that bears some geographic resemblance to Columbia.

Each is facing potentially career ending charges, for either racial

insensitivity or sexual harassment, which they find somewhat perverse, given Ben’s

South Asian heritage and Sila’s status as a prominent feminist scholar.

Their

lives will intertwine with a lonely Uber driver eager for social interaction,

two teenagers who stole a handgun from an active-shooter workshop instructor, the

musicians booked at Paris Blues, the bartender (and Sila’s accuser) Ike, and

the club’s cool-as-a-cucumber owner, Sam (transparently inspired by the

real-life owner Samuel Hargress Jr., who passed away last April).

Probably,

the most important aspect of the film is the real-deal music that drives

everything, giving urgency to the interpersonal conflicts. It features

musicians like Antoine Roney (brother of the late Wallace), William “Spaceman”

Patterson, and vocalist Camille Thurman essentially playing analogs of themselves.

They also exhibit remarkable flexibility, locking into funky grooves one minute

and then segueing into free jazz explorations when Sam suspects an undercover

dancing narc is prowling in the club.

The

intersecting drama is also often provocative, usually in the better sense of

the word. The administrative proceedings Ben and Sila face take on David

Mamet-ish dimensions, rendered in an Altman-esque style. While we are led to

suspect each contributed to their own predicaments, the film gives a sense of

how precarious it is to work in contemporary academia. Paris/Harlem does

not exactly take their sides, but it certainly is not an advertisement for

woke-ism.

The

deliberately rough-around-edges vibe does not always work. Frankly, Ike’s

opening riff on Slaughterhouse-Five almost comes across like a Tarantino

parody, so viewers should be advised it does not represent the rest of the

film. On the other hand, the scenes of Ben’s and Sila’s hearings have real

bite, precisely because you really have to seriously consider them to decide

which way they cut. Similarly, we see Sam turn on a dime from a fatherly figure

to someone who makes snap judgements based on superficial characteristics,

which is a very human habit.

Trauma from the Iran-Iraq War still lingers in both countries, but especially

for this Iranian father. A stray bomb decimated his family and ripped his

psyche apart. We will see just how profoundly the latter is damaged when Abed

Abest takes viewers inside his wounded subconscious in Killing the Eunuch

Khan, which screens as part of the (online) 2022 Slamdance Film Festival.

Descriptions

of this film border on malpractice. Anyone coming to Eunuch Khan expecting

a thriller that follows a serial killer who forces his victims to kill further

victims will be bitterly disappointed. That is some sort of allegory referenced

in the opening titles, but not subsequently chronicled on-screen. However,

there are literally tsunamis of blood that periodically cascade through the

father’s haunted house. There is definitely a case to be made that this is a

horror film, but it is not constructed to satisfy any conventional genre fans.

Do

not try to assign one-to-one symbolic references to everything that unfolds,

because that would be a fool’s errand. Just think of Abest’s images as the

fevered dreams of the father’s tormented sleep. Sometimes they feature “Eunuch

Khan,” who might be some sort of stand-in for the callous officials from either

country, who used their people as cannon-fodder.

If

you divorce yourself from a typical viewing experience, Abest offers some

absolutely stunning images. He has several long, complicated tracking shots

that could rival any filmtwitter gushes over. Plus, the father’s decayed house

on the border is an eerily memorable location. There are jaw-dropping parts to

this film, but as a holistic whole, Eunuch Khan lacks cohesion to its

radical vision. It probably represents a bit of a fall-off from his weirdly

brilliant Simulation, even though Eunuch Khan is arguably quite a

bit more ambitious.

Immanuel Kant wrote: “we can judge the heart of a man by his treatment of

animals.” By this standard, our judgement of the Iranian government should be

harsh. The clerics have proclaimed dogs unclean, so the government pays

bounties to those who hunt them down. Yet, many Iranians still love dogs,

because they are dogs, but they must do so secretly. Yassi and Aslan are more

open about their canine affection, running an underground dog shelter that is

probably not underground enough. Their efforts will break the hearts of dog

lovers in Mahmoud Ghaffari’s Doggy Love, which screens as part of the (online)

2022 Slamdance Film Festival.

Aslan’s

relationship with Yassi is dysfunctional, to say the least. They both have plenty

of issues and insecurities, but they are all their dogs (250 and counting)

have. Frankly, Yassi doesn’t even feel like she is in a relationship with Aslan,

but she does not have the heart to make that clear. She also wants to keep him

dedicated to their dogs. He constantly berates her for over-crowding their embattled

shelter on the outskirts of town. Yet, he is the one who always pulls over to

tend to wounded creatures, whom he inevitably brings home to the shelter.

At

about an hour in length, Doggy Love is short, but not sweet. Viewers

will feel for these poor pooches and the mismatched couple taking care of them,

regardless of their faults. For the first fifty minutes or so, Ghaffari plays

it cool and clever. There is no overt criticism of the wider Iranian society.

Yet, the cruel attitudes of their dog-hating traditional neighbors are hard to

miss—same for their misogyny.

However,

the film really lowers the boom in the closing minutes, when Aslan explains

most of Yassi’s sponsors are women, because Iranian women identify with her

canines’ plight. It is a heavy statement, but he means it.

There

is nothing fancy about Ghaffari’s film. It is filmed on the streets, with all

kinds of street smarts. What it lacks in prettiness, it makes up for in urgency.

It is a crying shame to see animals treated this way—and the harassment Yassi

faces is just ugly.

Secret dog love in

Iran has already inspired several films, most notably Jafar Panahi’s Closed Curtain. Ghaffari (who has had several narrative films at international

festivals) proves that Panahi exaggerated nothing (in fact, the situation on

the ground for Iranian Spots and Fidos might even be worse than Curtain suggests).

Highly recommended for anyone concerned with animal rights or human rights, Doggy

Love screens online through Sunday (2/6), during this year’s Slamdance.

The stories of Tiananmen Square Massacre survivors needed to be told. Years after Christine Choy filmed student leaders like Wu'er Kaixi regrouping in America, her footage finally sees the light of day in Violet Columbus & Ben Klein's documentary, The Exiles, which premiered at this year's Sundance. You can find my review exclusively at The Epoch Times here.

Usually, in movies or TV, high school reunions are either the setting for slasher

horror (Mostly Likely to Die, etc.) or super-awkward cringe comedy (D Train and so forth). These partiers returning for their fifteen-year get

off easy, because there is only one dead body, at least for most of the show

(granted, the cops “lose” a suspect or two, but they are dumb enough to simply misplace

them). Unfortunately, poor Aniq will suffer all sorts of comedic indignities. He

also finds himself the prime suspect in creator-director Christopher Miller’s The

Afterparty, which premieres today on Apple TV+.

Everyone

is excited to see the Vanilla Ice-ish rapper and actor “Xavier” at the reunion,

even though they all hated him in school, when he was known as Eugene. Nice but

nebbish Aniq is the exception, for reasons that will be revealed over time.

However, still attends, in hopes of re-connecting with Zoe, his former

lab-partner and eternal crush. Rather inconveniently, suspicion immediately

falls on him when someone pitches Xavier over the edge of his Hollywood Hills

mansion, to his death below.

Regrettably,

Aniq was passed out for most of the night and when he woke up, he immediately

started shouting incriminating threats towards Xavier, who would take his swan

dive shortly thereafter. Det. Danner and her bumbling partner, Det. Culp immediately

key-in on him, but at least they go to the trouble of getting the other guests’

statements, which collectively paint a Rashomon-ish picture of the

night.

Everyone

is comparing Afterparty to Only Murders in the Building, but it

is far less neurotic, because how could it not be. It also has its own peculiar

charm. Although Aniq is ostensibly a straight-man-like character, Sam Richardson

(who played a similar personality-type in Werewolves Within) gets a

surprising share of the laughs with his deadpan responses. He has appealing maybe-yes-maybe-no

romantic chemistry with Zoe Chao, as her namesake, and also nicely riffs along with

manic Ben Schwartz, playing his goofball friend (and failed musician) Yasper.

Based

on the seven episodes (out of eight) available for review, it seems Miller and

his co-writers were undecided whether Danner is dumb-as-a-post or

crazy-like-a-fox. Weirdly, Tiffany Haddish’s loud bull-in-a-china-shop

portrayal maintains that uncertainty, which is arguably a real trick. In

contrast, the totally on-point Ilana Grazer is scathingly acerbic as the boozy,

scandal-tarred Chelsea (think of her like Juliette Lewis in Yellowjackets,

but without the shotgun).

Amazon is truly leaning into fantasy as a genre. They already made a splash

investing in bestselling franchises like the recently launched The Wheel of

Time and the much-anticipated The Lord of the Rings. Rather

shrewdly, they have also managed to sort of license Dungeons & Dragons without

licensing Dungeon & Dragons, by adapting one of the campaigns played

by the Critical Role podcasting ensemble as an animated fantasy series. Matthew

Mercer’s The Legend of Vox Machina, offers plenty of fantasy elements

along with a whole lot of cussing when it premieres tomorrow on Amazon Prime.

“Vox

Machina” are a band of screw-up mercenaries who have stayed together this long

mostly out of habit. Somehow, all their bickering helps get them into a

fighting rhythm. Grog Strongjaw is exactly the meathead barbarian he sounds

like. Vex and Vax are half-elf brother-and-sister, who specialize in stealth.

Pike Trickfoot is a healer gnome. Keyleth is a druid, who is out to prove her worth

according to druidic traditions, while steely flintlock gunslinger Percy

Fredrickstein is out for vengeance (although his teammates do not know that

yet). Rounding out the group is Scanlon Shorthalt, a gnome bard, who will

remind casual fantasy fans of Tyrion Lannister from Game of Thrones,

except he is considerably more randy, to the point of being annoying.

In

the first two episodes, the Voxxers decide doing good might actually pay better

so they set off to hunt the archetypal monster terrorizing the Exandrian

countryside (it’s a DNR that turns out to be an epic fantasy staple). The early

misadventures are pretty derivative of countless other fantasy novels and films,

but things get considerably more interesting with the third episode, which

finds the VM heroes appointed guardians of the realm. They stumble across a much

more insidious threat to Exandria from an evil (and perhaps undead) villain,

who also has bad blood with one of Voxxers—really bad.

The

role-playing podcasters all reprise their characters for the animated show,

with Dungeon Master Mercer providing the voices of several non-player

characters. For those with no investment in the series, either Fredrickstein or

Vex and Vax might be the most interesting characters (due to their relative complexity).

The others either feel underdeveloped, like whiny Keyleth or incredibly broad, such

as Strongjaw and Shorthalt. Maybe it helps to know the latter from the podcast,

because his horndog shtick is relentless (judging from the first six episodes

provided for review).

Anna Politkovskaya. Boris Nemtsov. Alexander Litvinenko. Alexei Navalny was

supposed to join their names on the list of Putin critics who met conveniently

early deaths. However, he survived to expose his would-be assassins. In a

fitting irony, the Kremlin officially declared him a “terrorist” yesterday,

mere hours before Daniel Roher’s documentary Navalny, an up-close

chronicle of his recovery and return to Russia, premiered at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival.

Nobody

was really surprised when Navalny was arrested returning to his Russian

homeland in early 2021, least of Navalny. As viewers can see in the film’s

early scenes, Navalny was a master of social media, who built a large and enthusiastic

following throughout Russia, especially with younger generations (you can see

them in Alexandra Dalsbaek’s doc, We Are Russia). Odds are he could easily

unseat Putin in a legitimately fair election, but that is not how the

president-for-life plays the game.

Navalny

always knew he was a threat, but he assumed his prominence would protect him.

He was wrong, as he readily admits to Roher. In August of the super-fun year of

2020, agents of the FSB (what the KGB is now called) poisoned him with the nerve

agent Novichok (dubbed “LP9” by the Russians). We really do know that because

of an investigation conducted by Bellingcat journalist Christo Grozev and Maria

Pevchikh of Anti-Corruption Foundation (founded by Navalny). Viewers hear from

them a lot in the documentary and what they have to say is fascinating. Yet,

Navalny himself was able to secure independent verification in a spectacularly

dramatic fashion.

Those

who have followed Navalny’s case might already know he cold-called one of his attempted-assassins,

who basically confirmed everything over the phone. It is an absolutely electric,

jaw-dropping scene that has to be seen to be believed. Some of that footage

(that was shot by Roher and Niki Waltl, one of three cinematographers on the

project) is already in the public sphere, but the full context makes it even

more gripping.

Of

course, it was uncertain whether Navalny would even live that long. The

sequences covering his poisoning are also quite intense and profoundly

troubling. It is easy to see how scared the Navalny family was, as they fought

the suspiciously obstructionist Novosibirsk hospital for access to Navalny.

There is plenty there too that demands to be seen by the world at large. However,

Roher does his best to keep the Navalnys’ privates lives private, but it is

hard to maintain a hard-and-fast firewall for a subject that was poisoned by

Novichok and returns to Russia to face likely (and unjust) incarceration.

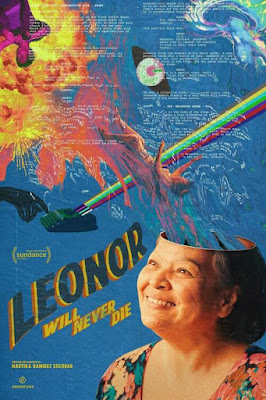

In the 1970s, Roger Corman started shooting films in the Philippines, because

they already had an established exploitation movie industry that worked fast,

cheap, and without excessively cumbersome safety regulations. Back in the day, Leonor

Reyes wrote the scripts. She has been retired for years, but serious trashy

movie fans still remember her. Of course, that won’t pay the bills, so she

tries to pull out her typewriter again. Unfortunately, a freak accident

submerges her in the world of her prospective script in Martika Ramirez Escobar’s

Leonor Will Never Die, which premiered at this year’s Sundance.

Sadly,

Reyes’ golden-boy son Ronwaldo died, but he still quietly haunts (or watches

over) the family, while she is stuck living with the other one, Rudie. She and

her husband Valentin split-up, but he remains a constant presence in the

neighborhood. With their power on the verge of disconnection, Leonor dusts off

an old unfinished screenplay, but she still struggles to finish it. Then she

gets bonked on the noggin, in a suitably unlikely manner, and proceeds down the

rabbit hole into her screenplay.

Suddenly,

she befriends and mothers Ronwaldo, the vengeful hero of her film,

transparently (but not identically) based on her late namesake son, as well as

Majestika, his new stripper girlfriend, whom he saved from the corrupt mayor.

Meanwhile, Rudie desperately tries to talk her out of her coma, as the other

Ronwaldo looks on and occasionally offers some advice.

Leonor

might

sound like the Filipino exploitation equivalent of light and frothy fantasies

like Ana Maria in Novela Land and Delirious with John Candy, but

it is considerably darker and more meta. The cool thing about Escobar’s film is

that it is true to sweaty, testosterone-driven genre it portrays. That means

Reyes very definitely finds herself surrounded by violence and sleaze, which might

limit the film’s appeal.

However,

Escobar consistently finds ways to surprise the viewer in the third act,

breaking down barriers between realities and self-referring like all get-out. There

is also some brilliant work from cinematographer Carlos Mauricio and production

designer Eero Francisco recreating the look, texture, and ambiance of vintage

1970s Filipino grindhouse.

Writing the Fourth World interrelated comic books for DC was a career triumph for

Jack Kirby, because he maintained artistic control. However, the characters

never caught on like his classic Marvel creations. Yet, that has allowed DC a

great deal of latitude in their subsequent reboots and reincarnations. A 2017 twelve-issue

limited-sequel-series earned acclaim for playing up the guilt and trauma still

carried by the escape-artist superhero, Mister Miracle. Writer Varian Johnson

now doubles-down on the abuse and angst of the character’s formative years in Mister Miracle: The Great Escape, a reimaging of his origin-story as a tory as a YA

graphic novel, which releases today from DC.

Others

can address the canonical issues of Great Escape, but for casual

readers, it stays relatively faithful to Kirby’s world-building. “Scott Free”

isn’t even Mister Miracle’s real name. It was given to him by “Granny Goodness,”

the sadistic headmistress of the brutal military academy, where he has been

effectively imprisoned (evidently, she is a fan of Ridley Scott and his

production company). When he “graduates,” he will become cannon fodder for Apokolips’

military (who apparently have a shorter life expectancy then the mechanized

infantry in Starship Troopers), if he’s lucky. She could always just

consign him to savage freakshow wastelands beneath the school.

Free

(who admits it is still a little early for his preferred superhero name)

intends to escape before that can happen. Fortunately, his forged an alliance

with Himon, a disgraced scientist and galactic explorer, who now works as a

common laborer in Granny’s academy. Himon’s granddaughter needs the kind of

medical treatment she cannot get on Apokolips, so he is counting on Free to

save her. Mister Miracle is down with the plan, even though it means turning

his back on his friends, until he starts to develop some extremely unlikely

chemistry with Big Barda. He really should not trust her, since she is the new

leader of the Furies, Granny’s jackbooted student warders, but he is a horny

teen.

Johnson

gives the Kirby’s Fourth World mythos a few clever twists, while staying

relatively true to the characters and their geopolitics. Unfortunately, he adds

a handful of a tired class warfare salvos, but they are pretty easy to let

slide by. Of course, the driving impulse to seek freedom is much more

important.

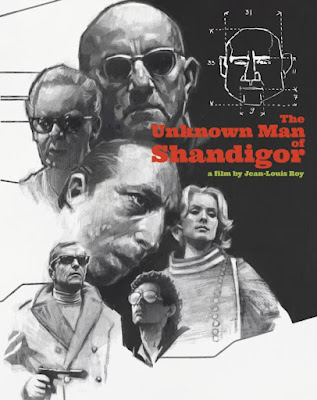

Life is cheap when you are a spy, especially when you are in a spy-spoof. You

could die at any moment for your country, but there is a good chance viewers might

laugh when it happens. There is a pretty high body-count in this spoof, but at

least one of the fallen agents gets a requiem serenade from none other than Serge

Gainsbourg. The mayhem is goofy but unusually stylish in Jean-Louis Roy’s

Euro-spy send-up The Unknown Man of Shandigor, which releases tomorrow on

BluRay.

Everyone

is interested in the “Canceler” formula developed by the mad scientist Herbert

von Krantz that holds the power of neutering nuclear war heads. Just about

every spy in the business is out to get it, including the Serge Gainsbourg ‘s

aptly named “Baldies” from France. There are also the Americans, led by the

Eddie Constantine-like Bobby Van and the Soviets, commanded by Shostakovich.

Frankly, it is a little unfair to make him the composer’s namesake, considering

the real-life Shostakovich had a very complicated and sometimes uncomfortable

relationship with the Communist Party.

The

formula is safely tucked away somewhere inside Von Krantz’s weird split-level

suburban McMansion, but only he and his albino assistant Yvan know where. Not

even his neglected daughter Sylvaine is privy to his secret, but it is somehow

related to their last happy family vacation to Shandigor. Understandably, she

still carries a torch for the dashing Manuel, whom she met there—but can she

trust him when they eventually reunite?

Shandigor

is

a lot like Godard’s Alphaville, but the story is easier to follow, the

comedy is broader, and sets and backdrops are even more stylized. Roy shrewdly

used the ultra-modernist buildings of Geneva’s NGO district and Barcelona’s

Gaudi buildings to create a trippy environment for his espionage frolics.

Frankly, the story is more than a little ridiculous and it is riddled with le

Carre-esque moral equivalence for each network of spies. However, Shostakovich

is arguably the most sinister of the bad lot.

Science fiction author Yasutaka Tsutsui is responsible for several adventures

into the subconscious. He created Paprika, who was immortalized in anime

by Satoshi Kon. Now, you can here his dream-working characters speaking French.

An overworked drone in a woman’s subconscious does his best to scrub

potentially upsetting images from her dreams in Leo Berne & Raphael

Rodriguez’s Censor of Dreams, which has been shortlisted for the best

short film Oscar (with Gus Van Sant on-board as an executive producer, granting

it some name recognition value).

Our

unnamed focal character and his colleagues work as dream censors in much the

same way Burt Reynolds and Tony Randall worked to bring about sexual functions

in the final segment of Woody Allen’s Everything You Ever Wanted to Know

About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask), but the tone here is far more serious. Each

night, they manically strive to keep the people and images of a great tragedy

she suffered out of her dreams. They only get a few minutes lead time, so they

are often forced to get creative.

Admittedly,

Censor cannot possibly compete with Paprika visually, but it

still has a good deal of inventive images that cleverly evoke the mystery of

the subconscious mind. Honestly, it can hold its own with a lot of Black

Mirror episodes and it has more heart and soul than Coma. In fact,

Berne & Rodriguez, in collaboration with their cinematographer Khalid Mohtaseb,

show a real knack for framing the things and places of our world in a way that

makes them look otherworldly.

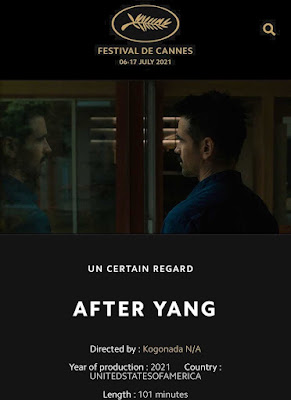

Yang is a way more advanced AI than Alexa. When you ask him to turn off a

light, he does it. In fact, he is truly a part of Jake and Kyra’s family, so

when he goes on the fritz, it is very distressing for them—and especially so for

their young adopted daughter Mika. They will have to prepare her to experience

grief for the first time, while learning there was more to their “techno-sapien”

“son” than they realized in Kogonada’s After Yang, which premiered

(online) as part of this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

When

Kyra and Jake adopted Mika from China, so they also purchased Yang, a life-like

AI-cyborg to serve as her big brother and help keep her connected to her

Chinese culture. However, they bought him certified-refurbished from a licensed

re-seller that apparently is no longer in business. Unfortunately, that means

when he breaks down, he most likely can’t be repaired.

Suddenly,

the two parents realize how much they had delegated their parenting

responsibilities to Yang. They also must come to terms with their own sense of

loss. However, the discovery of a cache of Yang’s saved memories leads Jake to

the discovery of Yang’s secret relationship with a clone and his previous lives

with other families, before they acquired him.

After

Yang is

a sensitive, character-driven science fiction story, in the tradition of films

like Marjorie Prime that happily does not involve terminally ill people

cloning themselves (as in Swan Song and half a dozen films before it). Kogonada’s

adaptation of an Alexander Weinstein short story still has clones and it very

definitely challenges viewers to reconsider what it means to be human. This near

future world features humanity living and working together with its sentient

creations in reasonable harmony, but the way people relate to AIs and clones is

clearly still developing.

Kogonada

de-emphasizes the flashy futuristic trappings, focusing instead on big ideas

and big emotions (although self-driving cars are already a staple of the

world). Indeed, the way he and actor Justin H. Min tease out intriguing new

dimensions to Yang’s character is one of the most successful aspects of the

film.

It is hard to get a good clean look at Fan Bingbing playing a heavily CGI’ed

mermaid in this film, but it is easier to see her here than in China, where she

is still being “rehabilitated” after the powers-that-be yanked her from the

public eye and “detained” her for several months in 2018. (Subsequently, she has

been considered to be one of the first celebrities to receive the “Peng Shuai

treatment”). Nobody will call this a “comeback” vehicle, but it is certainly a

curiosity piece. (You can also see the logo for the financially-precarious Evergrande’s

liquidated film unit in the opening credits, for extra added notoriety.) Our

protag—don’t call her the princess—forms a friendship with Fan’s weird mermaid

in Sean McNamara’s The King’s Daughter, based on Vonda McIntyre’s novel,

which opens today in theaters.

Louis

XIV has just returned victorious from war, but a would-be assassin’s too-close-for-comfort

bullet makes him suddenly mindful of his mortality. He is played by Pierce

Brosnan, so apparently the Sun King was Irish. Who knew? The court doctor, who

also dabbles in alchemy tells the king he can make him immortal, if his men can

capture one of the mermaids living in the lost city of Atlantis. He needs to

transplant its uncanny life force into the king—but it will only work with a

full-grown female. Of course, she will die in the process, but he can live (forever)

with that.

Meanwhile,

Louis summons the secret love child he tucked away in a convent to serve as the

court composer. Marie-Josephe D’Alembar is a rebellious klutz who could make

even Katherine Hepburn say: “you could carry yourself with a bit more grace,

kiddo.” She knows nothing of her true origins or her father’s intention to

marry her off to a wealthy young nobleman. Instead, D’Alembar falls in love

with Yves De La Croix, the slightly tarnished sea captain who captures the

mermaid.

It

is hard to believe this production was allowed to film on-location at Versailles,

but they were, way back in 2014. Obviously, this has been on the shelf for

years, for good reason. The effects are cheesy and so are the performances.

Brosnan looks embarrassed and Kaya Scodelario’s Miss Maisel-ish portrayal of D’Alembar

is ridiculously anachronistic. Honestly, Fan really doesn’t do anything except

let the FX team superimpose her head on the big fish. Ironically, only William

Hurt brings any sense of dignity to the film as the good Father La Chaise, an

original character not in McIntyre’s novel.

Some of these protags could be dubbed “Lara Croft, Civil Service Bureaucrat,”

or something like that. An American treasure hunting salvage company, not

unlike Odyssey Marine Exploration has discovered a fabulously rich Spanish

shipwreck, transparently based on the Our Lady of Mercy. Of course, they want

their sweat equity to be repaid with booty, but the dysfunctional Spanish

government stakes their legal claim to ownership. Fortunately, their American

attorney is the treasure-hunter’s old nemesis in Alejandro Amenabar’s six-part La

Fortuna, which premieres today on AMC+.

In

the late Eighteenth Century, Spain and England were technically at peace, but

sabers were rattling. To prepare for war, Spain recalled the La Fortuna as part

of a four-ship convoy, ferrying all the gold and silver they had plundered from

the New World, to fill their war-chests. Unfortunately, the British had the

drop on them and sunk La Fortuna down to Davy Jones’ locker, where it remained

undisturbed, until Frank Wild secretly discovered it off the coast of Gibraltar.

It

is a jackpot find, but he tries to be cagey in reporting it, so as not to tip-off

the Spanish government. However, Alex Ventura, a rookie foreign service officer

and Lucia Vallarta, a stridently left-wing archaeologist with the Cultural Ministry

suspect Wild discovered and cover-up the La Fortuna. Of course, they will need

some solid evidence if crusty old Jonas Pierce will have any hope of

challenging Wild’s claim in Federal court. Awkwardly, there seem to be elements

in the Spanish government that want them to fail.

Although

based on a real-life incident, La Fortuna plays out like the worst Clive

Cussler novel that he had the common decency to never write. There are tons of

scenes in conference rooms and courtrooms, but hardly any undersea adventure. That

would be okay of the legal thriller aspects were somewhat thrilling, but they

are not. Not at all. Plus, the relentless anti-Americanism goes beyond tiresome

to become outright self-parody.

Frankly,

it isn’t even warranted. In the real-life case, Odyssey constantly accused the U.S.

Federal government of siding against them and with Spain. The most notable U.S.

official interceding on their behalf was Rep. Kathy Castor (D-FL), but naturally,

Amenabar never lets facts get in the way of the “narrative” he “constructs.”

Sometimes, Iran's Islamist regime is described as Medieval, but there is also a

bizarrely Victorian aspect to the social structures they gave rise to. For

instance, creditors can essentially consign their defaulters to debtors’

prison. Such a fate is a terrible disgrace in a society that demands the

perception of virtue, if not the actuality. Rahim Soltani hatches an unlikely

scheme to free himself and rehabilitate his name, but complications quickly

ensue in Asghar Farhadi’s A Hero, Iran’s international Oscar submission,

which premieres this Friday on Amazon Prime.

Soltani

owes 75K to Bahram and he has no prospects of repaying him, since his former business

partner absconded with their funds. Therefore, he must serve a multi-year

sentence that gains Bahram nothing but retribution. Briefly, Soltani believes

his problems are solved when his girlfriend Farkhondeh finds a purse with

several precious coins on the street, but their hopes are dashed by a

precipitous decline in the price of gold.

Pivoting

during his two-day furlough, they craft a social media scheme, wherein Soltani

rebuilds his social virtue by claiming to find the coins himself and making a

show of returning them to their supposedly rightful owner, who would in fact be

the role-playing Farkondeh. Initially, the plan is a smashing success, winning

over the prison officials and a rehabilitation charity. However, Bahram is

unconvinced. As the creditor resists the chorus asking for his pardon, others

start chipping away at the holes and inconsistencies in Soltani’s story. The

whole affair turns into a big mess, in which many of the players share some

culpability, but Soltani is the one who really stands to lose.

Like

all truly grand tragedies, we can see how one agonizing thing will inevitably

lead to another, until poor Soltani will be completely buried under his own

schemes and deceptions. Yet, we can also almost see him wriggling out, which is

a source of genuine suspense. At one point, a character tells Soltani he is

either a complete simpleton or a calculating genius—and that is a perfectly apt

description of him.

It was probably HBO’s best original series ever. It could have whacked Tony

Soprano and massacred the Starks and Lannisters, but that is not how Fraggles

and Doozers roll. The endearing Jim Henson puppetry series was all about

singing and working together—and it still is. Somehow, HBO lost the franchise,

but it was quite a shrewd pick-up for Apple. After releasing a collection of

shorts, the franchise makes a full return with the first season of Fraggle

Rock: Back to the Rock, which premieres this Friday on Apple TV+.

The

basic premise is the same. Gobo’s Uncle Traveling Matt explores the human

world, reporting back to Fraggle Rock through postcards, offering satirical “Nacirema”-like

commentary on our human adult world foibles. He mails them to Doc’s apartment, through

which the world of Fraggle Rock can be reached via a hole in the wall. The

Great Hall of Fraggle Rock is supplied by water from a well maintained by the

ogre-like Gorgs, who try to stomp on Fraggles whenever they see them.

Fortunately, Gorgs are dumb as well as big.

It

is the same world, but in this slightly rebooted series, Doc is now a young

woman PhD student. The change of casting from an old white guy might check a

lot of woke boxes, but it doesn’t work so well on a practical level. It used to

make sense that the old absent-minded professor Doc was oblivious to the little

Fraggle creatures constantly running through his garage-workshop, but it makes

the young new Doc look pretty dim-witted (seriously, she is supposed to be a

scientist). However, Doc’s Muppet dog Sprocket is still cute and endearing.

The

same is mostly true for the new series, but the writing sometimes tries a

little too hard. For the next season, the battery of writers might want to ease

off on the teachable moments and pick the ones to really emphasize. Those that truly

worked this time around include an incident in the third episode, “The Mergle

Moon Migration,” wherein Red gets lost in an echo chamber. Frankly, it should

be required viewing for everyone on Twitter.

However,

the series takes a bit of a Roland Emmerichian turn with the last five episodes,

featuring multiple catastrophic threats to the extended Fraggle Rock

eco-sphere. First, the Fraggles inadvertently dry up the neighboring Craggles

water supply. Then the Doozers start building Doozer stick-structures with a

terrible tasting goo, so the Fraggles stop eating them, causing a

sustainability crisis. Then Junior Gorg dams up the Fraggles’ own water source.

It gets so bad, the oracle-like trash-heap also starts ailing. Yet, the tone is

never too intense or dire for young viewers.

Despite

the constant schedule of lessons learned, Back to the Rock has nice

energy. It is also more brightly lit and features more vibrant colors than we

remember from the original series (although that could a trick of the memory).

Perhaps most impressive is the consistently high quality of the original songs,

a number of which have generally catchy melodies (in a good, non-earworm kind

of way).

What is scarier than death? Living badly, without your full capacities. What

is worse than that? Regret for the mistakes that separated you from your loved

ones. At least that is what the experiences of an aging Argentinian man would

suggest. He will confront all these grim realities and

possibly also the supernatural (or perhaps not) during what could be his last

night on Earth in Gonzalo Calzada’s Nocturna: Side A—The Great Old Man’s

Night and its more experimental companion film, Nocturna: Side B—Where the

Elephants Go to Die, both of which release tomorrow as a “double bill” on

VOD.

Nocturna is sort of like

the horror version of Haneke’s Amour. In fact, scenes of the confused

Ulises lost in the halls of his once grand apartment building summon memories of

Jean-Louis Trintignant in a similar position. However, Ulises’ marriage to Dalia

is not as loving as the one portrayed by Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva. For

one thing, viewers are clearly invited to question whether she is even still

alive. Regardless, we learn from flashbacks Dalia bullied Ulises when they were

children and there is reason to believe the dynamic continued throughout their union.

Sadly,

Ulises’ strained relationships with his grown children is a profound

disappointment for him. Most of his human interaction is with the reasonably

patient but not especially warm building super. However, he also once knew the

upstairs neighbor Elena, who is apparently now dead and haunting the old couple

by pounding on their door each night. Eventually, we will figure out what

happened to everyone when Ulises finally starts piecing together his fragments

of shattered memory.

Side

A (107

minutes) is a surprisingly ambitious, yet fundamentally humanist take on

horror, aging, and the horror of aging that is radically different from Calzada’s

last US-distributed film, Luciferina. Arguably, the companion Side B (a

mere 67 minutes) is even more ambitious, representing a sort of Guy

Maddin-esque reverie, presenting the events of Side A through ghostly streams-of-consciousness. Side A stands alone and it is exponentially more accessible, so most of this

review will focus on it. There is an audience for Side B’s distorted analog

aesthetic, but casual viewers would need Side A to understand the

context of each scene.

Pepe Soriano plays Ulises in both films and it is a

relentlessly honest and cathartic performance (especially in Side A). The 92-year-old

veteran thesp is obviously credible as the physically and mentally declining

Ulises, but the guilt and remorse he projects from the screen is almost overwhelming.

He is also convincingly frightened to his bones.

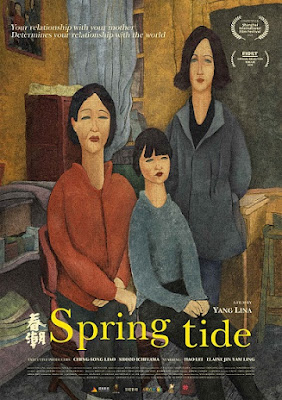

China experienced a literal “generation gap” when the best and brightest students

of the late 1980’s disappeared or sought asylum abroad following the Tiananmen

Square crackdown. Guo Jianbo was a little too young to have participated, but

she shares many of the protesters’ reformist sympathies. Her social conscience

contributed to the bitter acrimony dividing her from controlling mother, Ji

Minglan. Guo’s nine-year-old daughter Guo Wanting is caught in the crossfire between

her mother and grandmother in Yang Tian-yi’s Spring Tide, which

premieres Monday on OVID.tv.

There

is a lot of bad blood between Guo and Ji, but Guo is forced to make the best of

things, because her mother still has custody of her daughter, whom she was

forced to relinquish years ago. While Guo crusades against corruption as a journalist

(often to the chagrin of her ethically-flexible editor), Ji organizes local women

to sing patriotic songs for government-sponsored chorale competitions. Even

though she lived through chaotic times, but Ji now literally sings the Party’s

praises, for the sake of her slightly elevated position in the neighborhood. It

goes unstated, but this is surely one of the reasons she is able to maintain

custody of Wanting.

Soon,

their long-simmering resentments boil over once again. As usual, Ji focuses on

Guo’s greatest vulnerabilities, by trying to turn Wanting against her own

mother. Fortunately, the little girl seems to have a pretty clear handle on the

cold war raging around her, but it is still a terrible position to put her in.

Spring

Tide is

the second film of Yang’s envisioned thematic trilogy addressing the challenges

for modern women in contemporary China, but it is getting harder and harder to

tell this kind of story under Xi’s CCP. Frankly, it is a minor miracle it was

released online in China, considering one of the stories Guo investigates

recalls some infamous incidents of Party corruption involving school

administration. In fact, many viewers have interpreted Guo and Ji as analogs for

reformists and regime loyalists. Regardless, the bitterness of their

mother-daughter relationship is often brutal to watch.

The horror genre used to get a lot of mileage from music videos back when

they were a thing. Of course, there was “Thriller,” with Vincent Price and the other

guy, but there were also official soundtrack videos, like Alice Cooper’s “The

Man Behind the Mask” from Friday the 13th Part VI and J.

Geils Band’s “Fright Night” video. The general idea of thirty-eight minutes of

linked music videos telling a macabre story is a bit of a throwback, but the vibe

here is more experimental. According to wiki David Lynch was an influence on

electronica band Boy Harsher (vocalist Jae Matthews and producer Augustus

Muller), but uncomfortably trippy movies like Calvin Reeder’s The Oregonian and

Jason Banker’s Toad Road are more apt comps for the viewing experience

of The Runner, which premieres Sunday on Shudder.

The

blood smeared all over the face and clothes of this hitchhiker should be your

first clue not to pick her up. She is a serial killer, who might even have

supernatural powers. Yet, after each kill, she calls an older man, whose

relationship to her is unknown, but he clearly understands her nature.

Meanwhile, Boy Harsher and several of their special guests record in the studio

and have their videos played on an 80’s-vintage Night Flight-style

variety showcase.

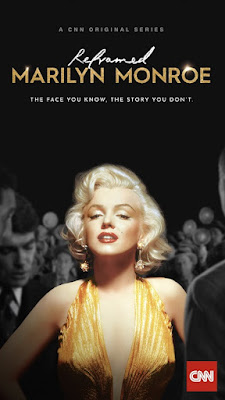

Marilyn Monroe is a lot like John Wayne—stay with me here—in that they are still

just about as popular now as they were at the height of their fame and they

still mean exactly the same things to their fans. In Monroe’s case, that would

be sex appeal first and foremost, but also music and comedy. Unfortunately, that

led to a career of typecasting and underestimation for the iconic movie star. A

nearly entirely female battery of commentators offers more sympathetic (and “feminist”)

spins on Monroe’s life and career in the four-part Reframed: Marilyn Monroe,

narrated by Jessica Chastain, which premieres Sunday on CNN.

Monroe

is still a huge star, but she had to fight for everything she had, before

tragically dying far too young. She grew up as an orphan, so she learned to

make the best of things. While working in an airplane factory during WWII, Monroe

caught the eye and lens of a photographer, who convinced her to start modeling

professionally. Subsequently, she signed as a contract player at 20th

Century Fox, but she was initially only cast in inconsequential parts, because

studio mogul Darryl Zanuck just didn’t get her.

Obviously,

she eventually caught on, with the aid of some unprecedented publicity.

However, the conflict between her and Zanuck was a constant refrain throughout

her career. Frankly, the best parts of Reframed explore that studio

intrigue. Yet, there are probably bigger villains in Reframed than

Zanuck, such as Hugh Hefner, who built his empire on her nude pictorial, but

never paid her a dime for the photo shoot she had signed away all rights to.

Given

her enduring stature, it is pretty amazing how short Monroe’s career was, only

truly “starring” in about a dozen films. Reframed nicely covers Some

Like It Hot, The Misfits, Bus Stop, and The Prince and the Showgirl (which

was the subject of My Week with Marilyn), but it gives rather short

shrift to Niagara and almost entirely ignores Otto Preminger’s River

of No Return. There are not a lot her star-vehicles, so it is a shame to gloss

over an interesting one.

On

the other hand, jazz fans will be happy Reframed discusses her

friendship with Ella Fitzgerald. She also gets credit for her USO tour, which

cemented her appeal to her military fans. Of course, her unfortunate marriages

are discussed in detail, but the treatment of Joe DiMaggio is totally unfair

(recycling abuse rumors, but not crediting the Yankee Clipper for his help

getting her out of the Payne Whitney psych ward). Yet, the biggest oversight in

Reframed is it ignores her conversion and continuing identification with

Judaism. Seriously, how did Adam Sandler overlook her for “The Hanukkah Song?”

Wisely, interview subjects do their best to defuse Kennedy conspiracy rumors,

especially her close friend Amy Greene.

Ray Donovan's business handling other people’s trouble (as a “fixer’). For

him, it is a really bad idea to mix business with family, but his thuggish

father Mickey Donovan constantly puts him in that awkward position. The son

intends to have it out with his loose cannon father, perhaps permanently David

Hollander’s Ray Donovan: The Movie, the feature conclusion to the

reasonably long-running series, which premieres tomorrow on Showtime.

If

you never watched the series, Hollander’s opening montage is more likely to

confuse than to illuminate. The crux of the deal is things have gotten really

bad between Donovan and his father, but they are still family. Mickey Donovan

made off to his old South Boston stomping grounds with a briefcase full of stolen

bearer bonds, so Ray chased off after him. To do what, even he is not exactly

sure.

The

truth is the actual plot of The Movie is pretty light and

straightforward. However, the flashbacks to the formative moments of their

father-son relationship should give Ray Donovan fans some Rosebud-style closure.

Hollander, the former showrunner, had anticipated a final season to wrap up all

the subplots, but a new corporate regime surprisingly axed the series. Remembering

the importance of franchise content, they subsequently put the movie into the

works. It definitely feels like a cut-and-paste job from the final series

outline, but the cast remains fully committed and all kinds of colorful.

Indeed,

it is easy to see why Liev (scourge of spellcheckers) Schreiber and Jon Voight had

fans so thoroughly hooked. As the title character, Schreiber broods so hard you

could use his forehead for Korean barbeque, while Voight is absolutely electric

and also strangely sad as the older but none-the-wiser father. Bill Heck perfectly

struts through the film as the younger but still erratic flashback Mickey.

Eddie Marsan is also quite poignant as Donovan’s Parkinson’s-afflicted brother

Terry, but the script by Hollander and Schreiber never gives him much to do.

It has witches, a ghost, and “something wicked this way comes.” “The

Scottish Play” is not exactly horror, but it was probably as close as you could

get in Elizabethan times. This still is not exactly a “Horror Macbeth,” but the

Thane exists in a landscape not unlike that roamed by the Knight in The Seventh

Seal, residing in a castle worthy of vintage German expressionism. Joel

(without Ethan) Coen mines considerable fresh inspiration from Shakespeare in

his visually striking adaption of The Tragedy of Macbeth, which starts

streaming Friday on Apple TV+.

It’s

Macbeth, so you should know the story by now. This time around the Thane

and Lady Macbeth are maybe a little older and a little more jaded, but the story

remains the same (and wisely so). However, the variations are particularly

interesting this time around, especially the three witches. In fact, it might

just be one witch, with three fractured personas or maybe she is a demonic

spirit. The way Coen presents her and Kathryn Hunter plays her/them leaves her

true nature open to interpretation, but whatever she might be, she is

profoundly sinister.

In

contrast, Coen largely de-emphasizes the ghost, rendering it a fleeting

illusion of Macbeth’s fevered mind. Of course, there are plenty of killings

that Coen stages with visceral intimacy. There is nothing more personal than betrayal

and murder, which Coen rubs Macbeth’s nose in—and immerses the viewer. However,

what really distinguishes the film is the starkly stylized set design that suggests

vintage 1930s Universal gothic monster films, by way of M.C. Escher. This film

looks amazing, in a cold, severe, drafty, imposing kind of way. Living in

Macbeth’s castle is almost unimaginable, but it makes for great cinema.

Running

an hour and forty-five minutes, Coen’s Macbeth is about equal in length to

Orson Welle’s adaption, and a bit shorter than the Michael Fassbender Macbeth,

and considerably briefer than Polanski’s take. It is briskly paced, but the

Thane’s transition from loyal vassal to murderous sociopath is more noticeably

abrupt. Of course, viewers know he is Macbeth, so they should be able to fill

in the gaps themselves.

Denzel

Washington fulfills our expectations in the notorious role and even manages to

surprise with the degree to which his Macbeth is tormented by his own crimes.

It is a massively moody and angsty performance, but also a very legitimate spin

on the character that we do not often see. In contrast, Frances McDormand’s

Lady Macbeth lives up to her reputation and then some.

This time it is a woman who is the Dr. Frankenstein-style mad scientist.

Unfortunately, her victims are young, fertile women, so it is not exactly a

blow against the patriarchy. In fact, the clients for her rejuvenizing fountain

of youth services are all rich old guys. Frankly, the old Baron was a much

nicer doctor of destruction (especially the Peter Cushing versions). In

contrast, Dr. Isabel Ruben is utterly reprehensible in Jens Dahl’s Breeder,

which releases today on VOD.

Mia

Lindberg has an awkward relationship with her mildly wealthy investment manager

husband Thomas, so she really has no idea how much he has been manipulated by

Ruben. She knows he has invested in her rejuvenation process, but she has no

idea he has also become an accomplice. Likewise, he does not fully appreciate

the horror show she is running until it is too late. Mr. Lindberg vaguely

understands she is keeping female subjects in her converted-factory research

facility under questionable circumstances, but he gets a real shock when the

abducted Russian au pair from across the street manages to escape and find her

way back to the neighborhood.

Thomas

delivers her back to Ruben, instead of the hospital like he promises Mia.

However, when Mia follows them via the find-my-phone app, she ends up in a cell

herself. Thomas is also a prisoner, but Ruben treats the money man somewhat

better. However, her henchmen, “The Dog” and “The Pig” give Mia their regular treatment.

Dahl

(who co-wrote Winding Refn’s Pusher) brings a lot of gritty noir style

to Breeder, but it is still a brutally violent and utterly joyless film.

Trust me, there are a number of scenes you will want to fast-forward through.

We do get some karmic retribution, but Dahl still can’t let viewers enjoy it.

It is an event, like the Wachowski’s returning to the Matrix, but Mamoru

Hosoda creating another virtual world of avatars is exponentially more

interesting. In Hosoda’s Summer Wars, the events within the fictional

online OZ held potentially disastrous implications for the real, physical world.

Technically, Susu Naito never confronts an imminent apocalypse when she enters

the virtual “U,” but she still faces life-and-death stakes IRL, based on her

actions as an avatar idol in Hosoda’s Oscar-qualified Belle, which opens

Friday in New York.

Naito

has been depressed and socially withdrawn for years, since her mother

heroically died saving an endangered child (who happened to be someone else’s

kid). The high school student has one friend, the brutally caustic computer

nerd “Hiro” Betsuyaku. She also has a protector, big-man-on-campus Shinobu

Hisatake, who would probably like to be something more, but she just can’t see

it in her present state of mind. Tellingly, she has been unable to sing since

her mother’s death, but when Betsuyaku helps her reinvent in U as “Belle”

(derived from Susu, which means “bell”), she becomes the most popular singer on

the virtual platform. Yet, nobody but Hiro knows her true identity, because of

U’s strict anonymity.

That

also means nobody knows who “The Dragon” is either. He started be beating the

heck out of everyone in U’s MMA tournaments, but his anti-social behavior

inevitably attracts the attention of U’s self-appointed guardians of order.

Frankly, their efforts to unmask Dragon’s identity might be even more disruptive

than his rage-benders. Nevertheless, Naito/Belle intuitively feels the pain

below his bruised exterior.

Acting

on instinct, Belle manages to follow Dragon to his castle-lair hidden in the

outer regions of U. There he broods with the company of loyal AI creature-servants.

It looks very much like Beauty & the Beast, but Hosoda is only

playing with the fable’s imagery. The secret of Dragon (sometimes actually

referred to as the “Beast”) is entirely different from any of his movie, TV, or

fairy tale predecessors.

In

fact, Belle resonates so deeply as a film because it makes it clear what

happens in physical reality is much more gravely important than the rivalries

of avatars in U. However, Naito must navigate U as Belle in order to reach the

real Dragon, who does indeed need her, whether he admits it or not. As a

result, Belle is probably the most emotionally fulfilling GKIDS release

since Ride Your Wave (on par with Poupelle of Chimney Town, which

they missed out on).

Visually,

it is also stunning. For Belle, Hosoda assembled an Expendables-level

team of animators, including Jin Kim (formerly of Disney) to design Belle and

Tomm Moore & Ross Stewart (acclaimed for Song of the Sea and Wolfwalkers)

for the fantastical world-building. Frankly, the resulting animation is even

more impressive than the baroque and trippy Summer Wars.

For comic book writers, the multiverse is a gift that just keeps giving. If

you want a character to be a fan of Superman comics, who eventually encounters the

DC superheroes in the flesh, you just do a little mixing of the parallel

universes—and then there they are. In this case, a Superman fangirl doesn’t

exactly meet her idol, but when he briefly crashes into her universe, it starts

her own super-origins story in the pilot episode of showrunner Jill Blankenship’s

Naomi, which premieres Tuesday on the CW.

Naomi

McDuffie loves Superman because he was an orphan just like her. She grew up happy

and well-adjusted as the daughter of bi-racial couple Greg and Jennifer

McDuffie, despite being a military brat. She also seems to be pretty well-liked

both at her high school and with her fellow Pacific Northwest local townsfolk,

maybe because she seems to have an ambiguous flirty relationship with several of them. Suddenly, Superman and a super-villain blast into their universe,

duking it out in the town square (only seen obliquely in cleverly assembled

cell phone footage), but McDuffie is unable to record any of it, because she

passes out from a tinnitus-like ringing sensation.

As

she investigates the presumed publicity stunt for her fansite, McDuffie is

struck by the suspicious behavior of Dee, the New Agey tattoo artist and

Zumbado, the used car salesman. The latter is already considered a villain, due

to his reputation for ripping off servicemen from the base.

Scenes

of the high school characters’ hip and casual acceptance of their ambiguous

sexuality often sound and feel like they were written by corporate diversity

trainers. However, the depiction of Army is refreshingly positive, as far as

the pilot shows. Her officer father is a totally cool dad, instead of a Great

Santini-style martinet and he is obviously the tolerant, inclusive type, since he

adopted her and married her mother. We don’t hear any cliched grievances

against the local base either, at least in the pilot, so maybe the series truly

has something for everyone.

It's like Fatal Attraction, except it was anonymous. Jordan Hines is soon to

be married, but he accepted an invitation for a masked sexual rendezvous, no

names attached. By the way, he is a Hollywood talent agent. If, as the

flim-flam man says, you can’t cheat an honest man, he is probably doomed. He

certainly has a lot coming, so his implosion is well-deserved in Jim Cummings

& PJ McCabe’s Beta Test, which is now available on VOD from IFC

Films.

Hines

is a big talker, but it is his friend and co-worker PJ who is the closer. That

means his position at his agency is a little shaky, but it doesn’t stop him

from inappropriately treating his assistant Jaclyn. (He is still a far cry from

Kevin Spacey in Swimming with Sharks, but HR should still have a talk

with him.) When he gets a purple envelope inviting him to a night of

debauchery, complete with a check-off list of kinks, he makes an attempt to

resist, but he can’t.

In

the days following, he cannot stop thinking about the encounter with the

mystery woman, who also happened to be masked. He snuck a peak, but he can’t be

sure who she was. Growing increasingly preoccupied, he starts a bull-in-a-china-shop

investigation of the purple envelopes, potentially linking them to the murder

from the prologue. Hines was already difficult to work with, but he becomes

increasingly erratic and even delusional as his obsession mounts.

It

is hard to say what Beta Test is, but if Eyes Wide Shut represents

a genre than it would be part of it. Cummings (part of the screenwriter-director

tandem) gives an amazingly committed and unhinged performance, but Hines is

such a loathsome person, most viewers will start rooting for the mysterious

unseen cabal pulling the string behind the scenes.