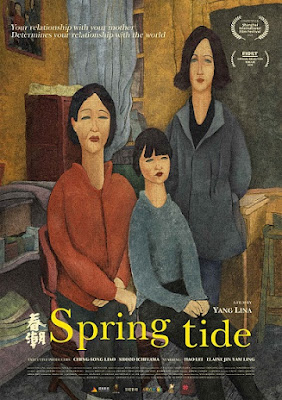

China experienced a literal “generation gap” when the best and brightest students of the late 1980’s disappeared or sought asylum abroad following the Tiananmen Square crackdown. Guo Jianbo was a little too young to have participated, but she shares many of the protesters’ reformist sympathies. Her social conscience contributed to the bitter acrimony dividing her from controlling mother, Ji Minglan. Guo’s nine-year-old daughter Guo Wanting is caught in the crossfire between her mother and grandmother in Yang Tian-yi’s Spring Tide, which premieres Monday on OVID.tv.

There is a lot of bad blood between Guo and Ji, but Guo is forced to make the best of things, because her mother still has custody of her daughter, whom she was forced to relinquish years ago. While Guo crusades against corruption as a journalist (often to the chagrin of her ethically-flexible editor), Ji organizes local women to sing patriotic songs for government-sponsored chorale competitions. Even though she lived through chaotic times, but Ji now literally sings the Party’s praises, for the sake of her slightly elevated position in the neighborhood. It goes unstated, but this is surely one of the reasons she is able to maintain custody of Wanting.

Soon, their long-simmering resentments boil over once again. As usual, Ji focuses on Guo’s greatest vulnerabilities, by trying to turn Wanting against her own mother. Fortunately, the little girl seems to have a pretty clear handle on the cold war raging around her, but it is still a terrible position to put her in.

Spring Tide is the second film of Yang’s envisioned thematic trilogy addressing the challenges for modern women in contemporary China, but it is getting harder and harder to tell this kind of story under Xi’s CCP. Frankly, it is a minor miracle it was released online in China, considering one of the stories Guo investigates recalls some infamous incidents of Party corruption involving school administration. In fact, many viewers have interpreted Guo and Ji as analogs for reformists and regime loyalists. Regardless, the bitterness of their mother-daughter relationship is often brutal to watch.

Hao Lei’s Guo is so painfully wounded, just watching her leads to sympathy pains. Conversely, Elaine Jin is a force of nature to behold as the steely and manipulative Ji. Frankly, they make Mommie Dearest look like Little Women. Yet, young Qu Junxi does crucial work holding the film together as Wanting. We can see the acute sensitivity of the little girl so often forced to act as a mediator, but she still just a kid, so she convincingly brings out her emotional immaturity, as well. Li Wenbo adds further complexity as old Zhou, Ji’s fiancée, who tries to go-along to get-along with everyone (Guo included).

Tide starts a little slow, but as the extent of the dysfunctional mother-daughter relationship unfolds, the film becomes profoundly gripping (and disturbing). Yang’s script pulls no punches and neither does Hao when Guo finally has her mother in a position to express all her accumulated grievances without interruption. It turns out the film has a lot to say about the prospects for women like Guo in Mainland China, without explicitly addressing political issues. Highly recommended, Spring Tide starts streaming Monday (1/17) on OVID.tv.