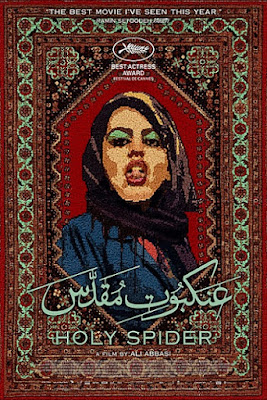

Saeed Hanaei was sort of like Iran’s version of Soviet serial killer Andrei Chikatilo (a.k.a. “Citizen X,” who continued to kill over decades, because the authorities deliberately ignored evidence linking his murders). Their prolific slayings exposed the corruption and incompetence of the respective regimes. In fact, the Islamist authorities were reluctant to stop the real-life Hanaei, for ideological reasons, because he only targeted “fallen” women working on the streets of Mashhad, the spiritual capitol of Shia Islam. Rather logically, it will be a woman journalist who exposes him in Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider, which opens tomorrow in New York.

Just checking into a hotel in Mashhad is an ordeal for Rahimi, since she is a single woman, unaccompanied by a man. She has to pull her journalist credentials, threatening a scandal in the papers. Rahimi is here to investigate the “Spider Killer,” since the local authorities clearly lack a sense of urgency.

To make matters worse, Rahimi’s bad reputation (quite scandalously, she filed a sexual harassment complaint against her former boss) has followed her to Mashhad. Nevertheless, Sharifi, the cautious local reporter who has received boasted calls from the killer agrees to help her investigation. However, winning the trust of the city’s prostitutes will be very difficult. Yet, they keep coming home with the murderous Hanaei, because that is what their business requires.

Holy Spider is Columbo-like in the sense that it reveals Hanaei’s identity as the killer right from the start. Abbasi also vividly depicts in his brutality, in stark, uncompromising terms. The misogyny of Iranian society also comes through loud and clear, especially during a scene in which Rahimi barely escapes an attempted sexual assault, at the hands of Mashhad’s police chief. For a so-called “holy city,” Mashhad looks like a pervasively predatory environment.

Yet, the investigation is only half the story. The rest of the film consists of the trial, wherein Hanaei tries to ride his public popularity to an acquittal, on the grounds his murders were theologically justified. Much to Rahimi’s concern and disgust, there is a very real chance Hanaei could pull it off.

For obvious reasons, it was Denmark that selected the Danish-based, Iranian-born Abbasi’s film as its International Oscar submission, rather than Iran. However, Abbasi filmed on location in Jordan, which doubles convincingly for the grim, dark streets of Mashhad (at least for viewers who have never visited, but have seen a number of Iranian films).

Holy Spider is definitely a visceral indictment of institutionalized injustice, intolerance, and sexism in contemporary Iranian society. However, it is also a potent hybrid serial killer thriller and courtroom drama. Indeed, the uniquely perverse aspects of Iran’s justice system greatly complicate the prosecution and consequently generate greater suspense than an equivalent case ever could, in just about any other jurisdiction.

In a performance of great personal courage (considering the possibility of subsequent reprisals), established Persian thesp Mehdi Bajestani is frighteningly intense as Hanaei. It is not the physical violence that makes him such a monster. It is his absolutely conviction in the righteousness of his murders.

Likewise, Zar Amir-Ebrahimi’s portrayal of Rahimi is gritty, gutsy, and often quite harrowing. Initially, she very directly conveys a sense that the journalist is already a survivor, which may very well have prepared her for the nasty opposition she will face. Weirdly, the saddest, most tragic performance might come from Arash Ashtiani as Sharifi, who is obviously attracted to Rahimi, but too cowardly to cowardly to act on his feelings.

Denmark might claim Holy Spider, but it is still a great Iranian film. (Ironically, Abbasi’s less politically-charged fantasy Border was previously submitted by Sweden.) Regardless, this is an amazing fusion of dramatic sensitivity of the best Iranian dramas with the tense, nocturnal aesthetics of film noir. Very highly recommended, Holy Spider opens tomorrow (10/28) at the IFC Center.