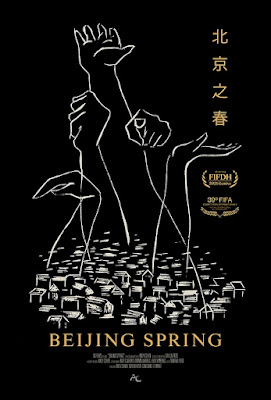

For Chinese artists, things could only get better when the Cultural Revolution ended—and they did—to an extent—for a while. During the thaw of the early Deng years, a group of artists emerged that pushed for liberalization in the artistic sphere and more democratic governance. Many of them are now living abroad (for obvious reasons). Andy Cohen and Gaylen Ross chronicle the “Stars Art Group and the related samizdat magazines that revolved around Beijing’s short-lived “Democracy Wall” in Beijing Spring, which opens Friday in New York and Los Angeles.

The “Stars” group intended their name to be modest, signifying them as small points of light, rather than super-stars in the Western sense. Although many members directly challenged Party censorship, many largely non-political artists were attracted to the Group, simply because they wanted to create without the CCP’s interference, including nude studies, which were banned under Mao.

Eventually, the Group mounted an underground exhibition on the gates of the National Arts Museum. When the government dismantled and confiscated their works, the artists staged the first Tiananmen Square demonstration. That would be the one truly nobody has heard, yet it ended much more peacefully. For a while, the Stars Group was even allowed to exhibit legally, until the Party got a good hard look at some of their work. Wang Keping’s carving “Silence,” in which the knot of his wood serves as a gag for its contorted face, was a particularly notable offender.

Beijing Spring is an absolutely terrific film because it both reports critically important historical incidents and showcases some remarkably striking art. Indeed, it is visually much more interesting than 99% of well-meaning docs that secure theatrical distribution. For those wondering, Ai Weiwei was a late joiner to the group, but he is only briefly seen in Cohen & Gaylen’s film, probably because he and they did not want him to overshadow the other artists, who are lesser known internationally, but played greater roles in the Group’s development.

When watching the film, it is striking just how much more rigid and totalitarian the PRC has become under Xi-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Deng was keenly interested in what the Western press wrote and they in turn had greater access to average man-in-the-street opinion. Yet, inevitably, the arts documentary evolves into a thriller, when the surviving artists explain their clandestine efforts to save Democracy Wall activist Wei Jingsheng, who was on-trial for his writings and facing potential execution.

Throughout the film, Gaylen & Cohen incorporate some remarkable 16mm film shot by Stars members that was smuggled out of the PRC. They have a heck of a lot of primary sources and the testimony of many of the Stars Artists and their circle, including Wei, Ai, Wang, Qu Leilei (now in the UK), Ma Desheng and Li Shuang (both now residing in France).

The film aptly quotes Mao’s Little Red Book that explicitly states “there is no such thing as art for art’s sake.” That oppressive mindset explains why the Stars Group were so hungry to create and express themselves. It captures a remarkable time that did not go far enough and ended far too-soon, but it was still greatly significant. Very highly recommended for the history and the art it documents, Beijing Spring opens this Friday (12/10) in New York at the Cinema Village.