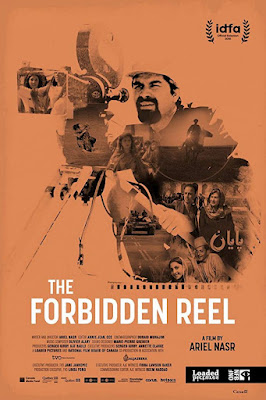

Rather remarkably, the staff of Afghan Films already saved their film archive from the Taliban once. Sadly, they will probably have to do it again, because Joe Biden got bored with Afghanistan. Hopefully, Taliban enforcers have not seen this documentary, but wisely the employees of the state film agency was already racing to digitize their archive, in recognition of the nation’s continuing instability. Ariel Nasr documents the history of Afghan cinema and the efforts to save it in the NFB-produced documentary, The Forbidden Reel, which screens online as part of the Smithsonian’s Left Unfinished: Recent AfghanCinema series.

Not surprisingly, the series also features What We Left Unfinished, the story of five incomplete, rediscovered Soviet Era films that offered in window into Afghan cinematic history. In fact, the director, Mariam Ghani (who also happened to be the daughter of former President Ashraf Ghani, now in exile in the UAE, for obvious reasons) appears throughout Reel, as one of Afghan Film’s chief supporters and consultants.

Not unexpectedly, the Taliban did indeed come to burn their country’s cinematic heritage. However, the forewarned Afghan Film employees were able to hide their true archive, by serving up their storeroom of international films instead. As of 2019, they were well into their digitization campaign, with Ghani’s assistance.

Initially, the Soviet-era was seen as a boon for filmmaking, but as the puppet government imprisoned and executed more and more Afghans, many of the directors attached to Afghan Films joined the Mujahideen, serving in the filmmaking unit attached to Ahmad Shah Massoud’s fighters. The moderate commander was one of the most effective at battling the Soviets, but he was tragically assassinated by his more extreme Taliban rivals, which directly led to an existential crisis for Afghan Films.

When watching Forbidden Reel, it is clear Afghanistan does not have to be the way it is. Most Afghans want to work hard, take care of their families, and maybe take in a movie now and then. Yet, a lack of will on our part turned back the clock to 2001. Perhaps most chillingly, we understand many of the people interviewed by Nasr are now in grave danger, if they have not managed to secure safe passage out of their country. Obviously, they can’t expect much help from us. We still have Americans we have yet to evacuate, but the Biden administration is loudly patting itself on the back, because they believe the total number is “fewer than 12.” (We’re midway through December, by the way.)

We will also probably be denied some interesting future Afghan cinema as a result. Nasr incorporates some intriguing images from the archives, including some wonderfully melodramatic romances, featuring women without scarves or face-coverings, as well as some gripping footage from Massoud-aligned Mujahideen war documentaries. Who knows what Afghan cinema could become if it had a chance to grow and develop without the periodic interruptions of the Taliban and Soviets?

Arguably, Forbidden Reel is a more comprehensive and compelling examination of Afghan cinematic history than What We Left Unfinished. It unambiguously indicts the human rights abuses of both the Soviets and the Taliban, while celebrating Afghan Films’ commitment to preserving its culture. Highly recommended, The Forbidden Reel screens online through December 26, via the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler film program.