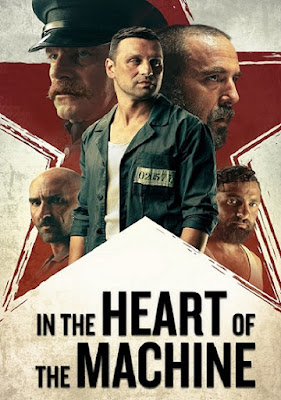

Bohemy, an inmate serving time in 1978 Communist Bulgaria, considers his best days those he spends toiling as an unpaid laborer, in a state factory, because that is his only connection to everyday human behavior. Usually, the brutality is mostly confined to the prison. However, all bets are off when the sadistic Captain Vekilsky and the notorious axe murderer “Hatchet” are there on the same fateful day in Martin Makariev’s In the Heart of the Machine, Bulgaria’s official International Oscar submission, which screens during the AFI’s European Union Film Showcase.

The complicated thing about Communist prisons is figuring out how truly guilty your fellow prisoners might be. Hatchet definitely killed his brother—and he has yet to forgive himself. However, the Lennie Small-like death-row inmate has experience with heavy equipment, so Bohemy convinces the warden, Colonel Radoev, to allow him to borrow Hatchet, to help fulfill their doubled quotas. If Bohemy (meaning “Bohemian,” his ironic prison nickname) can pull it off, he might just get a parole. Radoev is a bit corrupt, but in a pragmatic, world-weary kind of way.

Unfortunately, Vekilsky is just a brutal martinet. Yet, even he is not inclined to provoke Hatchet. Instead, he mostly focuses his wrath on Needle, another hardened criminal. However, the guard is not inclined to indulge Hatchet, when he refuses to work on his machine, until a pigeon trapped within its gears can be safely rescued. Therefore, Hatchet launches an insurrection of one, taking Vekilsky and the rookie guard Priv. Kovachky (a.k.a. “Junior”) hostage. That puts Bohemy in a real rock-and-a-hard-place situation, trapped inside the shop with Hatchet, while the military police outside, led by Captain Kozarev (the man who framed him for the murder), prepare their assault.

Machine is an unlikely mixture of gritty prison drama and symbolic fable, yet the basic premise is based on fact. There was a bird trapped in heavy machinery that inspired a defiant work-stoppage, but it was resolved with considerably less violent conflict. Of course, the corruption and abuse of the Communist era “justice” system are also very definitely based on historical realities. Bohemy was no anomaly. In many ways, he is a Bulgarian everyman representing thousands, but Alexander Sano’s grounded and conflicted portrayal makes him feels like a very real person, rather than a symbolic composite.

Hristo Shopov also supplies an intriguingly nuanced performance as Radoev, perhaps one of the most sympathetic senior Communist officials you can find in a film that honestly recreates the Communist experience. Clearly, helping perpetuate injustice takes a toll on his conscience and karma.

Mariev uses the confined space to build tension and shrewdly plays wildcards like Vekilsky and Needle to periodically stir up trouble. Just when the film appears poised to launch into grand allegorical flights, he brings it crushingly back down to earth. It is not exactly a feat of tight-rope walking, but it is impressive to behold. Nevertheless, Machine is sort of like a Bulgarian Shawshank Redemption, but its climatic escape to freedom must be only symbolic, because true escape was impossible in a captive nation like Bulgaria, at the time. Highly recommended, In the Heart of the Machine screens tomorrow (12/12) and Thursday (12/15) as part of the AFI’s EU series (and it streams on Freevee).