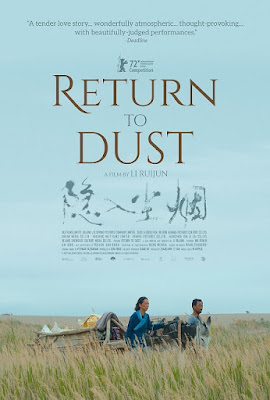

Usually, is great news when an indie release becomes a sleeper hit. However, it got Li Ruijun’s hardscrabble film banned in China. Obviously, it is banned, since it disappeared from theaters and streaming platforms, but there was no formal explanation issued. It is not like you can ask these questions on Chinese social media either. Perhaps the better question is how did Li’s searing portrait of rural Chinese poverty and societal indifference ever get approved in the first place? Life is bleak in Gansu (on the outskirts of the Gobi Desert), as depicted in Return to Dust, which opens today in Brooklyn.

Ma Youtie is a humble man, who is not comfortable with people. It is just as well, considering how contemptuously his surviving younger brother treats him. Much to his surprise, his disinterested family arranges his marriage to the disabled and much abused Cao Guiying, largely so they can both be rid of them. They do not have much choice in the matter, but they develop a supportive and eventually loving relationship together, as they eke out a subsistence dirt-farming living.

Ma and Cao get no support from their families, so they essentially squat in abandoned farm houses. Unfortunately, the provincial government has launched a program to raze such derelict buildings, much like in Detroit. Ma also literally has his blood sucked dry by the local oligarch, with whom he shares a rare blood-type.

To satisfy the censors for the film’s original release, Li tacked on an unconvincing epilogue that bizarrely contradicts all the exploitation Ma and Cao endured and the callous disregard of their community that viewers just spent over two hours watching. This is a withering indictment of contemporary Mainland society, but Li’s pacing is decidedly deliberate. It is easy to imagine CCP censors starting the film and skipping ahead to the end, thereby missing the totality of the couple’s Job-like suffering.

This is not a charming little slice-of-life film, which makes its grassroots breakthrough in China so surprising. It can be a tough go, but it is keenly sensitive to its main characters’ trials and travails. Wu Renlin (Li’s uncle) is an amazingly intuitive and expressive thesp. Technically, he is not a “professional” actor, but this Li’s third film he has appeared in. The dignity and the sorrow he conveys are absolutely devastating. Likewise, Hai Qing (a major star, primarily in TV, but also from films like Sacrifice) will quietly destroy viewers as Cao.

Dust can be slow. There is no getting around that fact, but Li captures some stunning images of the harsh arid environment. Like the Badlands, the landscape surrounding them is often beautiful, but in overpoweringly ominous kind of way.

For the record, Return to Dust still carries the state film authority’s “dragon” seal and the dubious epilogue, but some closing end-titles that repeated the “happy socialist” ending were mercifully cut. Regardless, this is a deceptive placid-looking film, because the predatory cruelty it portrays (from the provincial government, the families, the community, and the oligarch) is profoundly shocking. Highly recommended for fans of “slow cinema” and socially conscious “kitchen sink dramas,” Return to Dust opens today at the BAM Cinema.