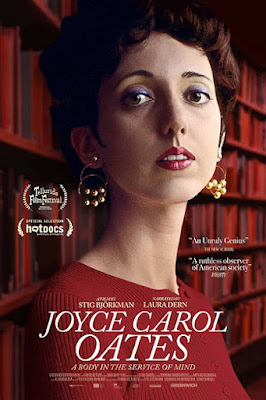

Stig Bjorkman certainly had a number of advantages in his choice of documentary subject. As of yesterday, she has published two memoirs and a collection drawn from her journals, as well as a wealth of fiction and non-fiction writings inspired by her life. Plus, for someone who describes herself as a “private person,” she recorded quite a few television interviews over the years. If you want to become an expert on Joyce Carol Oates, your biggest challenge will be finding the time to read all the primary sources, including the book of interviews Bjorkman released in Sweden. For years, he regularly proposed a potential documentary. Finally, she agreed to participate in what became Bjorkman’s Joyce Carol Oates: A Body in the Service of Mind, which opens Friday in New York.

Obviously, JCO is first and foremost a writer, as acres of paper-stock can attest. She is best known for long “great American novel”-style works that use the family saga as a vehicle for social and political commentary. However, readers who do not share her Ivy League perspective might find her genre outliers more rewarding, including her more mass market pseudonymous thrillers, which Bjorkman duly covers. (I particularly recommend her gothic mystery Mysteries of Winterthurn). Black Water is also a significant work, of manageable novella length, transparently inspired by the untimely death of Mary Jo Kopechne in Ted Kennedy’s car.

Unfortunately, JCO’s politics are much more predictable and much less interesting. During the Trump era, she became something of a Twitter warrior, which seems like a colossal waste of her time and ours. As the son of a Vietnam veteran and a Vietnam-era vet, her and her husband’s relocation to Canada during the war and her shallow anti-war sentiments are disappointing. Apparently, the plight of the Vietnamese “boat people” refugees and the sacrifice of those who did serve left little impression on her. For those with a somewhat different perspective, this section of Bjorkman’s film is a bit of a poison pill.

Of course, none of that is surprising. At least the film makes up some lost ground with its sensitive treatment of JCO’s late-in-life discovery of her grandparents’ German Jewish heritage, which makes it easier to identify with the writer and academic. Mathias Blomdahl’s jaunty, jazz-influenced score, featuring Per “Texas” Johansson on clarinet and saxophones, also helps a lot.

Throughout the documentary, Laura Dern (who starred in the 1985 adaptation of Smooth Talk) reads selections from JCO’s titles, but the impact varies greatly from excerpt to excerpt. Presumably, A Body in the Service of Mind (a subtitle that doesn’t quite sound right outside the context in which it appears in a JCO book) is not a film to convert, appealing to established fans instead. Only recommended to her ardent admirers, Joyce Carol Oates: A Body in the Service of Mind opens this Friday (9/8) at the IFC Center.