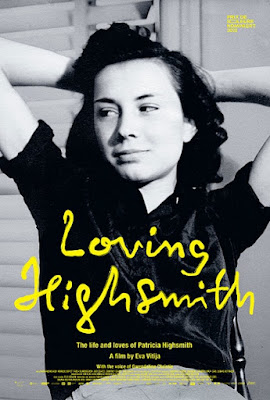

This is just a reminder Patricia Highsmith also wrote books. It will be important to keep that in mind during this documentary, because it relentlessly focuses on the private life she wanted to keep private. As a result, Highsmith most likely would have been horrified by Eva Vitija’s Loving Highsmith, which opens Friday at Film Forum.

Throughout her life, Highsmith kept journals she did not want other people to read. In fact, she wrote large notes at the beginning of later journals emphasizing what she wrote within was for her eyes only. Vitija excerpts those diaries extensively throughout Loving Highsmith.

For the first six years of her life, Highsmith lived with her grandmother in Texas and consequently always retained some sense of being a Southerner. In fact, you can somewhat see a Flannery O’Connor sensibility in her work, especially in regards to the dark side of human nature. The Texas relatives Vitija interviews seem relatively accepting of her sexuality, but they are still a bit surprised when the filmmaker informs them Highsmith once had a fling with her cousin.

Highsmith made her name with Strangers on a Train, but Hitchcock is only mentioned in passing. However, the novel Carol (a.k.a. The Price of Salt) is discussed at length, because of its lesbian themes. There is a bit of discussion of Tom Ripley, her signature anti-hero, but a great deal of that centers on the fourth book, The Boy Who Followed Ripley, because it was partially shaped by one of her own romantic relationships.

Loving Highsmith will make viewers miss the Formalist school of literary criticism, which held it did not matter who or what an author might be. The only valid question was whether the book was any good. Instead, it is clear Vitija is only documenting Highsmith because of her sexuality. Her work is of secondary importance.

That is a shame, because Highsmith is a hugely significant writer, who arguably transcends genre. She has inspired filmmakers like Hitchcock, Claude Chabrol, Claude Miller, Rene Clement, Wim Wenders, Todd Haynes, and even Sam Fuller (who helmed an episode of the Chillers anthology, based on her short stories). Indeed, the most interesting sequences are those in which Highsmith explains her books are not really about crime or murder, but the feeling of guilt, or the absence thereof.

To some extent, Vitja creates a sympathetic portrait of Highsmith, explaining her difficult relationship with her mother and her late-in-life status as a tax refugee from France, forced to seek shelter in Switzerland. However, her focus on the personal approaches the intrusive. At one point, Vitija builds anticipation regarding the identity one of Highsmith’s great loves, only to announce she died before she could interview her, so she will not reveal her name, out of respect for her privacy.

That is the right decision, but it is just perverse to then continue hyping the mystery around her, like if William Alland had discovered the significance of “Rosebud” in Citizen Kane, but then announced to newsreel viewers he was still keeping it secret out of respect for Mr. Kane’s privacy.

Loving Highsmith is a good example of what is wrong with current documentaries. Except for Carol, it does little to promote interest in her body of work, but instead exploits her very private life to make judgements on social norms of her era. Highsmith deserves better than this. Not recommended, Loving Highsmith opens this Friday (9/2) in New York, at Film Forum.