According to reports, Padre Pio (a.k.a. St. Pio of Pietrelcina) exhibited the stigmata, healed the sick, bi-located, and faced multiple investigations from the Vatican that were intended to discredit him. However, none of those things are in this film, because why would they interest Abel Ferrara? Instead, viewers will witness many of the future saint’s long dark nights of the soul. If you thought he was tortured and tormented before, wait till you see him get the Abel Ferrara-treatment in Padre Pio, which opens tomorrow in New York.

WWI has ended and the men of San Giovanni Rotondo are making their triumphant homecoming—but not all of them. This is the first example of how capricious and unfair fate can be to the villagers. After the armistice, the land-owners expect life to return to normal, but socialist rabble-rousers are organizing to defeat the elite’s hand-picked candidate for mayor. Where is Padre Pio in all this? Back at the monastery, wrestling with the Devil and his personal demons.

Is that disconnection Ferrara’s whole point? Is this a statement on the Church’s divorce from average people’s struggle to survive. That is certainly a valid interpretation, but it feels somewhat at odds with the genuine (if somewhat eccentric) Catholic spirituality of his best religiously themed film, Mary.

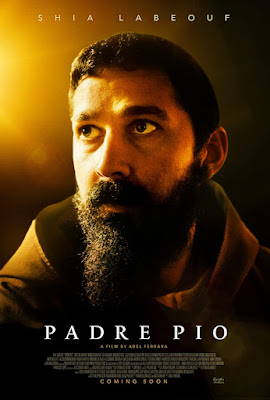

Even by Ferrara’s raggedy standards, Padre Pio is a rather disjointed film. There are moments of brilliant cinema, such as opening scene of the soldiers’ homecoming. You can see Ferrara’s operatic fervor in all the secular passion play sequences. However, whenever Padre Pio rages against the darkness, you half expect Shia Labeouf to start baring his bottom, like Harvey Keitel in Bad Lieutenant. Evidently, Ferrara was struck by the coincidence Padre Pio started experiencing the stigmata around the time of the San Giovanni Rotondo massacre, but the connection he makes in his mind is not reflected on screen.

Ferrara also picked a heck of a time to stop working with Willem Dafoe. Labeouf makes a poor substitute, even though it was Dafoe who recommended him to Ferrara. There are some nice performances in Padre Pio, especially Cristina Chiriac, as a recent war widow who refuses to grieve, and Salvatore Ruocco as the veteran, whose advances she spurns, because he works as a foreman for the town’s noble family. However, Labeouf just cannot find the right key or pitch for Padre Pio, which is a big problem, since the film is ostensibly about him.

And then there is Asia Argento in a wild, gender-bending cameo. Padre Pio is most certainly an uneven film, but it will still demand several chapters in book-length studies of Ferrara—and her scene could probably warrant an entire chapter to itself. Is she, or rather he, the Devil? It is not impossible.

Ferrara handled some of these themes much more successfully in Mary. Nevertheless, this is probably his boldest, most passionate film since Pasolini. (Incorporating the spooky gospel blues of Blind Willie Johnson’s “Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground” was definitely a cleverly evocative touch.) Yet, the sum of it all is rather obscure. There are sweeping set-piece scenes that could inspire your old lefty uncle to start belting out verses of “The Internationale,” but, ultimately, that is not nearly enough to recommend Padre Pio when it opens tomorrow (6/2) in New York, at the Roxy Cinema.