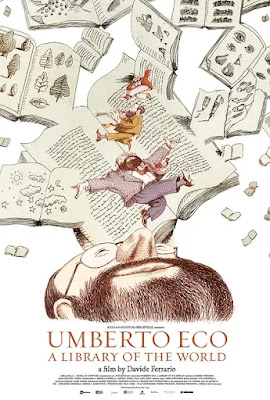

Umberto Eco became an international bestseller with a mystery about a poisoned book. Yet, probably nobody better loved the look and touch of the printed page, especially those in ancient volumes, than he did. Despite knowing better, he rarely used gloves while perusing the rare, centuries-old tomes in his 50,000-volume collection. David Ferrario takes viewers into the Eco library, to examine the philosophical ideas and eccentric academic fascinations of the late great writer in Umberto Eco: A Library of the World.

Obviously, Eco was not an internet kind of guy. He likens it to the information overload that plagues that hapless central character of Jorge Luis Borges’ “Funes the Memorious,” who was driven mad by his ability to remember every single little detail of his life, no matter how trivial. It does rather make sense Eco was a Borges kind of guy, even though the Argentine fantasist was not writing in the 17th Century.

Ferrario is particularly interested in Eco’s pessimistic view on the long-term epistemological impact of the internet. To over-simplify matters, he did see a potential for it to make people dumber rather than smarter. He spoke of three types of memory: the organic stored in brains, the vegetal stored on wood and paper, and the mineral stored in silicon. He rather liked the vegetal version.

Eco also had a passion for Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit who wrote richly detailed studies of the natural sciences that were almost entirely wrong. Yet, the systemic logic of his “alternate science” fascinated Eco. It is easy to see the influence of Kircher’s hermetic world view and the rare occult and alchemy books Eco also collected in his novels. Weirdly though, Ferrario spends very little on Eco’s fiction and almost none on the conspiratorial Foucault’s Pendulum, which seems like his most relevant novel for our current times.

Each section of Ferrario’s library culminates in an Eco monologue recited by one of the author’s admirers, in a suitably cinematic library setting. The selections emphasize Eco as an epistemologist. Each reflects his talent for language, but several boil down to rather pithy arguments that a bibliophile affix to their fridge with a cat magnet. However, the writer’s literary fans will learn a good deal about Eco the family man, through warmly engaging interviews with his widow, daughter, son, grandson, and protégé.

Eco’s books are fascinating, because of the deep erudition that produced them, but they are also page-turners, thanks to sinister “hidden hands” working to subvert the search for the truth. Despite the dumbing down of the internet, we are increasingly living in societies worthy of Borges’ stories. Each side of the political spectrum accuses the other of being “conspiracy mongers,” who happen to be engaged in secret plots to undermine democracy for their own enrichment.

Eco had seen it all before, in pages dating back four hundred-some years. The writer would probably enjoy Ferrario’s biblio-centric approach, but he might have hoped it delved a bit deeper into the substance of his writing, rather than skimming easy sound bits off the top. Recommended as a pleasant and much overdue profile of the novelist and thinker, but not as the final word on his ideas and fiction, Umberto Eco: A Library of the World opens this Friday (6/30) in New York, at Film Forum.