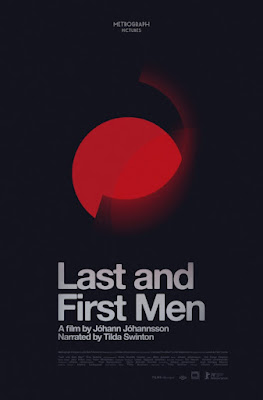

Many millennia from now, will human beings still be wearing cloth masks? The voice from the future never specifies, but apparently, we evolved to have telescopic eyeballs on the top of our heads. Mankind survived several extinction-level events, but fate will eventually catch up with us on the plains of Neptune in the late composer Johann Johannsson’s unlikely but spiritually-faithful adaptation of Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, which is now screening at the Metrograph.

We are hearing a communication from the far, far future. They want something from us in the past, but it is not to recruit us to fight aliens, as in The Tomorrow War. Unfortunately, it will be solar events and cosmic gaseous bodies that spell mankind’s demise, but they are resigned to it at this point. Their business is more philosophical.

This is why Stapledon was always considered so unadaptable. His best-known novels were not about ray-guns and rocket-ships, but rather the rise and fall of galactic civilizations and species. Although Johannsson and co-writer Jose Enrique Macain incorporate a mere fraction of his text into Tilda Swinton’s anesthetizing voice-overs, they faithfully convey the vibe and sweep of his work.

To accompany these grand and sometimes dire descriptions of future humanity, Johannsson films the imposing and often crumbling Brutalist monuments of the former Yugoslavia. These de-humanized vistas are lensed in starkly glorious black-and-white by cinematographer Sturla Brandth Grovlen. Some of them even look akin the statuary of Easter Island and the neo-primitivist masonry designed by Burle-Marx.

There is a narrative of sorts to Last and First, but no characters per se. Yet, there is plenty to intrigue the curious mind, like the development of “navigators,” a “hardy” folk, who prefer to travel space beyond the range of future man’s hive-mind telepathy. So, there will still be Red-Staters thousands of millions of years from now.

Visually, Last and First is an arresting spectacle and the music composed by Johannsson and Yair Elazar Glotman is suitably eerie and other-worldly sounding. (Sigur Ros fans should definitely dig it.) Ironically, the film also shows why so many sf fans probably never brought themselves to dig into the Stapledon novels they might have on their shelves. At seventy-one minutes, Johannsson’s film is quite manageable, but the prospect of plowing through over 300 pages without characters or dialogue and very few proper names to speak of, is a somewhat daunting prospect.

If you are intrigued by the idea of Stapledon, Johannsson gave us an accessible entryway into his vision of future-history. Granted, “accessible” is a relative term here. Yet, for fans of experimental film (very much in the tradition of Ben Rivers’ Slow Action) and ethereal music, the film’s artistry and ambition are impressive. It is now playing in New York at the Metrograph.