The so-called “Russian Separatists” who terrorized Donbass Ukrainians really weren’t separatists.

They wanted to become a Russian vassal territory. In 2014, Russian-backed “separatists”

used Russian-supplied arms to shootdown Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 from

territory completely controlled by Russia. Yet, Putin’s regime never faced any

serious consequences. What kind of behavior did that incentivize? We’re seeing

it now. Donbas was seeing then, even including a local Russian sympathizer, who

suffers like Job from his allies and the wrath of his Ukrainian-loyalist wife

in director-screenwriter-editor Maryna Er Gorbach’s Klondike, which has

a special screening tonight at Anthology Film Archives.

Russia and

its “separatists” tried to deny responsibility for MH17, but they had already

claimed responsibility, thinking it was a Ukrainian troop transport. Tolik

ought to be able to empathize with the grieving families, because the

itchy-trigger-fingered Russian mercenaries also blew off the front wall of his

house. His wife Irka is less understanding. Not only is she Ukrainian, but she is

also 7-months-pregnant—and now literally living in rubble. Tolik wants to take

her somewhere safer, but his neighbor, Sanya, a local fixer for the Russian

mercs, “borrowed” his car.

Tolik’s

marriage might be strained, but his relationship with his Ukrainian-loyalist

brother-in-law Yaryk practically constitutes a cold war. Both are pigheaded and

passive-aggressive in ways that do Irka

no favors. Yet, it is hard for outsiders to see why her husband shifted his

loyalties to the rogue separatists. They regularly hold him at gun-point, stole

his car, bombed his house, and then demand he kill his cow to feed them. To

paraphrase The Producers, where did the separatists “go right?”

Indeed,

that absurdity is at the heart of Klondike. The title itself might

baffle initially, but it is a veiled reference to the scavenging of luggage—a gold

rush—that commences after Flight MH17 crashes near Tolik’s farmhouse. There is

much of Samuel Beckett and a lot of The Honeymooners in the three main

characters, but it will be lost on many people, because the wartime

circumstances are so grim.

Er Gorbach’s

approach is also art-house all the way, which will further serve to keep some viewers

at arm’s length. Yet, there is often a chilling point to her quiet, long-takes,

which often reveal ominous movement on the far horizon. Make no mistake, her

shots are composed, in close artistic collaboration with cinematographer

Svytoslav Bulakovskiy. The fearful truth is that whatever you see in the

distant background will inevitably arrive in the foreground—almost surely portending

bad things.

Russia has deliberately targeted Ukrainian artists and filmmakers, like Oleg

Sentsov, but maybe that strategy backfired in the case of filmmaker Alisa

Kovalenko. After the Russians arrested, interrogated, and detained Kovalenko

while she was filming the illegal Donbas invasion in 2014, she resolved to

enlist and defend her country if Putin were to invade the rest of Ukraine,

which he did. At that point, considered herself a soldier rather than a

filmmaker, but she inadvertently made a film anyway, thanks to her video

diaries and video letters to her son. Ultimately, she incorporated that footage

into her latest documentary. Their separation is difficult for her as a mother,

but she fights for his future, as she explains in her documentary, My Dear

Theo, which screens this Friday at the 2025 Camden International Film Festival.

In a

way, this film started back in 2014, just like the war, but everyone outside of

Ukraine simply hoped it would go away if they ignored it. Of course, that only made

things worse. Through family connections, her husband took Theo and his mother

to safety in France, leaving Kovalenko to fight—but that is exactly what she

wanted.

Initially,

Kovalenko and her comrades are on the march outside Kharkiv—until they suddenly

stop. Clearly, her unit is accustomed to the constant shelling. There certainly

seems to be good chemistry between them all, which makes the final rollcall of

the fallen soldiers seen in the film such a slap in the face.

Kovalenko

incorporates some battle scenes, but it really isn’t an embedded combat

documentary like 2,000 Meters to Andriivka. This is a very personal

statement from Kovalenko that often eloquently explains why she took up to

defend her country. Sometimes, the extremely personal POV limits its

effectiveness as a film to rally global public opinion. Nevertheless, it starkly

establishes the stakes for Kovalenko and her fellow soldiers.

It was like Dunkirk for animals. There were 5,000 beasts, of nearly every variety,

at the Ferman Ecopark, all of whom had to be evacuated after Putin’s invasion.

Nobody was prepared to pack up their own lives and flee, but transporting the zoo’s

entire population would even more challenging. Yet, finding a place to take

them all would be even trickier. The resulting rescue mission was a logistical nightmare

and a humanitarian imperative the surviving ecopark employees revisit in Joshua

Zeman’s documentary, Checkpoint Zoo, which opens this Friday in

theaters.

Initially,

Oleksandr Feldman thought the ecopark’s location outside Kharkiv, near the

Russian border, was a perfect location. That was before Putin launched his war.

Conceived as a combination wildlife shelter, zoo, animal rehabilitation center

(both wild and domestic), and therapy animal clinic, the ecopark was home for

wide variety of species. Unfortunately, it landed right in the middle of no man’s

land during the Battle of Kharkiv, just beyond the final Ukrainian government

checkpoint (hence the title), where it endured artillery barrages from both side

that fell short.

It was

several days before staffers could return to feed and water the animals, but

some habitats remained too dangerous to reach. The animals grew hungrier, which

made the predators dangerous.

Anyone

with an ounce of compassion for God’s creatures will be deeply disturbed and

angered by animal suffering documented in Checkpoint. The sight of the

emaciated and trembling moose is especially shocking. However, it is important

to remember there is only one man to blame for their condition: Vladimir Putin.

Indeed,

the film makes this point several times, even when the starving and terrified

big cats lash out at their frustrated care-givers. Of course, the Russians did

their best to make a bad situation worse, launching mortars at the ecopark

whenever their drones spotted multiple vehicles at the Feldman facilities. Zeman

and the sound design team also viscerally convey a sense of how the sounds of

war terrify and disorient the animals, because of their heightened auditory

senses.

The tiny Ukrainian village of Andriivka went from obscurity to tragic notoriety in ways

much like the Korengal Valley in Afghanistan. For months, Ukrainian forces

fought literally centimeter by centimeter to liberate the village from its

Russian occupiers, only to fall back when the counter-offensive stalled. After

documenting the shocking carnage of Russia’s scorched earth tactics targeting

Ukrainian civilians in 20 Days in Mariupol, director-producer-cinematographer

Mstyslav Chernov embedded with the Ukrainian defense forces to capture the

battlefield conditions they endure in 2,000 Meters to Andriivka, which

opens this Friday in theaters.

Before Putin’s

illegal invasion, Andriivka was a town of no particular importance, unless you

lived there. However, during the Ukrainian counter-offensive, it occupied a

location strategically close to Russian supply lines. Of course, safely

reaching the village was truly an ordeal. Surrounded by bombed-out wasteland, Ukrainian

forces had to traverse a narrow strip of surviving forest that had been mined

and fortified with fox-holes.

Many

offensives had already failed when Mstyslav and his colleague co-producer-co-cinematographer

Alex Babenko tag-along with the latest push. Consequently, everybody

understands the punishing nature of the fighting they face. As the Ukrainians haltingly

progress, Mstyslav and Babenko mark their progress: 100 meters, 200 meters and

so on. It is slow going, made even more frustrating by some of Mstyslav’s

editorial choices.

Chillingly,

Mstyslav has a habit of rather announcing the fatal ends met (in subsequent battles)

by the Ukrainian soldiers he interviews at considerable length, usually towards

the end of their very personal and dramatic segments. Frankly, many in the Ukrainian military tried to dissuade them reporting on the front line—with good

reason.

Although

Mstyslav and Babenko certainly document the Russians’ brutal tactics, the film

itself often feels demotivating. Whether intentional or not, it emphasizes the

futility of the sacrifices made during the bloody assaults on Andriivka. While

never pro-Putin, the messaging is decidedly mixed, which makes its release this

week rather ironic, considering it comes at a time when Trump and his many of

his loyalists are finally turning against Russia and endorsing support for

Ukraine.

Indeed,

if you can force a MAGA friend to watch one Ukraine documentary, make it Mstyslav’s

previous 20 Days, which will reinforce their disgust with

Putin’s bloodlust, rather than 2,000 Meters, which could lend credence

to their belief Ukraine simply cannot win in the long run.

Bernard-Henri Levy has a Ukrainian artillery position named in his honor—and he

couldn’t be more proud. Probably no other philosopher has spent as much time in

war-zones, thanks to his documentaries covering the Ukrainians struggling to

repel Russian invaders and the Kurds’ battle against ISIS. Frankly, Levy has

seen more of the Ukrainian front lines than most senior Russian officers,

partly because Ukraine keeps inviting him back and partly because Russian

officers keep getting killed in action. Yet, the media and politicians insist Ukraine

cannot win. Levy examines the boots-on-the-ground realities of Ukrainian morale

and battle-worthiness in his Our War, which opens today in New York.

Even

wearing a flak jacket, you can immediately recognize Levy as he tours the

Ukrainian forces in the field. That why it is so gutsy that he returns so often.

At this point, he is on a first-name basis with Zelensky and has long-term

relationships with several senior commanders. He also meets many enlisted men

and junior officers, like Oksana Rubaniak, who also happens to be a poet, much

like her late boyfriend, another fallen soldier. Touched by their stories and

their verse, Levy promises to publish them both in France.

Throughout

the documentary, Levy and his crew hear plenty of shells landing nearby and sometimes

even whizzing past them. He also documents some of the destruction wrought be

Putin’s scorched earth tactics. The images are shocking and appalling, but they

can’t equal the visceral horrors of Mstslav Chernov’s 20 Days in Mariupol,

but few films can.

Unfortunately,

there is an awkward co-star. That would be our current President, whose bizarre

Oval Office meeting with Zelensky happened during filming. It leaves a bitter

taste that Macron’s administration is seen as a bigger advocate of freedom. Yet,

the truth is Biden talked a better game, but he never really walked the walk

either.

Yet, that

scene directly into Levy’s titular thesis. He repeatedly argues that Ukraine is

fighting the war now, so the rest of Europe (and even the U.S.) won’t have to

fight it later. It is not just his interpretation. Russian officials like Dmitry

Medvedev say the same thing, but more abrasively, on Russian national

television.

Levy

also forcefully contradicts conventional wisdom. Interview after interview

attests to an undiminished resolve, both among the Ukrainian miliary and

civilians. Yes, they could use more and better arms and supplies. At one point,

Levy counts twenty Russian mortars for every Ukrainian response. However, the

Ukrainians make the most of what they have. Those who nauseatingly use the term

“forever war” to advocate abandoning Ukraine need to understand Putin started

this “forever” war and it will only end when he withdraws. Until then, Ukrainian

patriots will continue to defend their homeland, even if Trump or Lula ask them

surrender.

That comes through

loud and clear throughout Levy’s latest film. Highly recommended as a timely

reality check regarding the state of Putin’s illegal war, Our War opens

today (6/11) at the Quad.

In

retrospect, schools were clearly closed for far too long during the Covid era.

Kids need school for both education and socialization. That is why Ukraine has

labored and sacrificed to keep schools open during Putin’s war. Education

continues, but the impact of the war is inescapable in Kateryna Gornostai’s

documentary, Timestamp (dedicated to her fallen brother), which screens

during this year’s New Directors/New Films.

As one

graduation speaker observes, this year’s graduating class lived out their

student years almost entirely during wartime conditions, if we count the 2014 Donbas

invasion. Obviously, things got even worse in 2022. Yet, Gornostai documents

several graduations, only one of which was sadly virtual, because the school’s home

city had been completely razed to the ground by Putin’s military.

Somehow,

in-person schooling continues, but the experience is much different from what

American viewers might remember. Elementary school children now receive regular

instruction on how to identify and report booby-trapped toys left on the streets

to maim them. Older secondary students learn how to tie-off torniquets, which

involve the titular “timestamp.” Even the coursework for advanced architecture

and engineering students has adapted to the times, because all new structures now

incorporate some kind of bomb shelter.

Not

surprisingly, instruction is often interrupted by air raid sirens. Even the

national standardized test for university admissions now makes allowances for

wartime disruptions. Altogether, it is a sad, bitterly cruel state of affairs.

Admittedly, some younger children appear somewhat traumatized, but Ukrainian

students in general exhibit an inspiring resiliency.

Presumably,

Putin and his trolls would say Ukraine’s music would be no match for Russia’s

advanced weaponry. Yet, here we are, going into 1,107th day of Putin’s

2-day war. We have also seen Ukrainian farmers carting off the wreckage of

Russian tanks on their tractors. Meanwhile, Russia cannot shut up Ukraine’s

defiant musicians. Ryan Smith documents the role Ukrainian musicians play both

within the military and on the homefront in Soldiers of Song, a

documentary supported by the Governor George Pataki Leadership Center, which

releases today on VOD.

Think

of it as “soft power” that turned hard as a diamond. When Putin launched his

illegal invasion, Ukraine’s musicians were just as shocked as the rest of the

world, but they found their talent could bolster spirits in bomb-shelter and on

the streets (when not under artillery barrages). Soon, the Ukrainian military

formed special musician’s units to maintain morale. Do not even consider

accusing them of wokeism. The American military has many special active duty

bands, many of which have histories dating back decades or even centuries.

Remember the Spirit of ’76 is literally a fife and drum trio.

The

Ukrainian musical morale-boosters take on many different roles. Some are

enlisted, while others, like Svitlana Tarabarova perform in USO-like

battlefield tours. The music also varies considerably. Tarabarova is sort of a Ukrainian

Taylor Swift, who used to perform relationship-themed singer-songwriter-style

pop. However, her music has recently taken a more serious turn (for obvious

reasons). In contrast, Slava Vakarchuk and the band Okean Elzy rock hard, but

can also go acoustic (they no longer tour Russia, where they built a

substantial fanbase, again for obvious reasons).

Tragically,

the war came to Vasyl Kryachok, artistic director of the Mariupol Chamber

Philharmonic, when Russia dropped a bomb on the Mariupol Theater, while 1,200

fellow musicians, staff members, artists, and their families were sheltering in

its basement. He is currently in-residence with the Kyiv Chamber Orchestra, yet

again, for obvious reasons.

Perhaps

the most personal and dramatic story is that of Sergiy Ivanchuk, an opera

singer in training, happened to be evacuating a clinic when he was sprayed with

five bullets, one of which was perilously near his spine. Fortunately, one of

the doctors patched him up enough to save his lung. Nevertheless, his recovery,

including a return to performances, is almost miraculous.

According to the actors based in Kyiv, Ukrainian theater overwhelmingly reflected a

Russian influence, until Putin’s illegal invasion. Since then, they have increasingly

looked towards the European avant-garde for inspiration. Of course, Putin does

not care about culture, but it is another example of Russia’s loss of

international prestige. French theater director Ariane Mnouchkine is exactly the

sort of artist the Ukrainian theater world has been drawn to. To show her solidarity,

Mnouchkine travels to Kviv to hold an intensive workshop, which Duccio Bellugi-Vannuccini

& Thomas Briat documented in Kyiv Theater: An Island of Hope,

premiering tomorrow on OVID.tv.

Throughout

her residency, Mnouchkine heard drone raid sirens nearly every night, but

fortunately, she never witnessed catastrophic-level destruction. Nevertheless,

her traveling company staff fully understood that was a very real possibility,

but they joined her anyway. Yet, throughout the workshop, both the Ukrainian

and French participants deliberately avoided explicit political subjects and

references. The Ukrainians had already had more than their fill.

Instead,

we watch numerous improvisation exercises that often resemble out-takes from

Samuel Beckett plays. Frankly, these very theatric theatrical performances are

the least interesting parts of Vannuccini & Briat’s doc, but they get a

majority of the screentime, in a film that clocks in a whisker shy of an hour.

Slava Leontyev is an enemy of Putin’s blood-thirsty Z thugs in two ways. He is

a soldier defending his Ukrainian homeland against an Imperialistic invasion

and an artist preserving Ukrainian art against a cultural genocide.

Collaborating with his wife, he has created remarkable porcelain figurines.

Working for the first time as a filmmaker, he now documents the atrocities of

Putin’s war as they happen in Porcelain War, co-directed by Brendan

Bellomo & Leontyev, which is now playing in New York.

The

art Leontyev makes with his childhood friend, art school classmate, and

life-partner Anya Stasenko combines Ukrainian tradition with their own

whimsical sensibilities. Figurines like their dragonlings are ornately

decorated, but their shapes and expressions are quite appealing, even cute. Not

surprisingly, their figurines have become moral boosting mascots for Leontyev’s

“Saigon” Unit, who specialize in dangerous missions in compromised territory.

Porcelain

also serves as a rather clever national metaphor for Leontyev and Stasenko. As

a material, it easily breaks, but can withstand extreme heat and easily

restores if it is buried for centuries. The aptness of the comparison to Ukraine

is obvious, especially as we watch the Saigon Unit taking fire, as the fight

their way towards wounded infantrymen needing medical assistance.

The

third focal artist is Andrey Stefano, the couple’s closest friend. Until Putin’s

unprovoked invasion, Stefano worked as a painter, but he shifted his focused to

filmmaking to document the horrific events unfolding around him. Almost all the

footage was filmed by the primaries, but Stefano has the sole cinematographer

credit. Obviously, he too understands art’s role as a method of resistance and bearing

witness. Yet, his primary concern is always his two daughters, whom he managed

to safely shuttle out of the country.

Polish director Maciek Hamela followed the example of Jafar Panahi, helming his

latest film from the driver’s seat. Panahi had to operate undercover making Taxi, because

the Iranian regime banned him from filmmaking. In contrast, Hamela voluntarily took

the wheel to shuttle Ukrainians to safety in Poland. Not merely a driver,

Hamela documents average Ukrainians’ oral history of Putin’s illegal invasion throughout

In the Rearview, which releases today on VOD.

Together

with his cameraman riding shotgun, Hamela ferries a constant stream of

families, seniors, students, and a few cats across the Polish border. Thanks to

his Russian fluency, he is unusually well-qualified for the job, which frequently

requires Hamela to talk his way through checkpoints.

It

quickly becomes clear a generation of Ukrainian children have been deeply traumatized

by the invasion. Families have been fractured, trapped in different shelters,

unable to contact each other for long stretches of time—if they are lucky. Of

course, many of Hamela’s passengers have lost loved ones.

Hamela’s

film might also explain why the DRC is one of the few African nations that have

spoken out against Putin’s war. It turns out Hamela’s minivan sometimes doubles

as an official ambulance, as when he delivers a gravely injured woman from

Kinshasa to a Polish hospital better equipped to treat her. According to his

patient-passenger, Russian troops opened fire on her and a group of fellow

Congolese students, even though they obviously did not look Ukrainian.

Nevertheless, they were still potential witnesses to Russian crimes against

humanity.

If you think all Millennials and Gen Z’ers are annoying, you haven’t met Ukrainian

Millennials and Gen Z’ers. There is nothing frivolous about them and none of

them have time to whine about micro-aggressions. They are too busy worrying

about the exploding macro-aggressions Russia keeps launching at them. Ukrainian-American

filmmaker David Gutnik captures the lives of Ukrainian artists working under

Russian bombardment, several of whom also served as crew on the documentary in which

they are subjects, The Rule of Two Walls. It opens this Friday in New

York.

Although

Rule of Two Walls is not nearly as harrowing and horrific as Mstyslav

Chernov’s extraordinarily important 20 Days in Mariupol, you will still

see bodies burned to a crisp by Putin bombing campaign. To put it more precisely,

Gutnik is compelled to record the brave Ukrainian journalists who are compelled

to record the truth of this particular war crime.

For

most of the film, Gutnik turns his lens on Ukrainian filmmakers, hardcore metal

musicians, painters, and gallerists. Ordinarily, they would be the hippest of

the hippest. However, since Putin’s full invasion, they have consciously

embraced traditional Ukrainian culture as another form of deliberate

resistance.

That

even includes Ukrainian religious traditions, even though some still cannot

quite call themselves believers. Regardless, the agnostic have always been the

minority in the devoutly Christian nation. In fact, Gutnik records a tellingly ironic

riff on the old adage about “no atheists in fox-holes.” Would an atheist even

be in a fox-hole in the first place they wonder, because that kind of commitment

requires a belief in something.

Rule

of Two Walls stimulates

further thought and provokes genuine outrage. It offers yet another valuable

perspective on Putin’s continuing war crimes. It also makes it clear how

profoundly Putin and his followers misjudged Ukrainian unity and resolve. They

more his Z-thugs try to erase Ukrainian identity, the more the Ukrainian people

re-assert it.

Do you like dolphins? If so, you should despise Putin. Since the launch of

his illegal invasion, the Ukrainian wildlife reserve on the Black Sea has found

the corpses of at least 5,000 dolphins, but they estimate thousands more have

died. Clearly, animals have suffered from Russia’s military aggression, just

like the Ukrainian people. Yet, despite the chaos and danger, ordinary

Ukrainians have risked their lives to rescue animals both wild and domestic. Viewers

need to watch their brave efforts, which Anton Ptushkin documents in “Saving

the Animals of Ukraine,” premiering this Wednesday on PBS, as part of the

current season of Nature.

It

sure is funny how everyone who was so concerned about the animals in the

Baghdad Zoo have had so little to say about the animals of Ukraine. Regardless,

the entire world saw images of desperate Ukrainian refugees carrying their

beloved pet cats and dogs. As a result, at least one NGO talking head had to

dramatically rethink they way he thought about refugees. Inevitably, many pets

were still left behind, often not intentionally, but rather due to unexpected

Russian bombardments. Zoopatrol was organized to save those animals, either by

jail-breaking them outright, or noninvasively feeding them through front-door

peep-holes (this mostly works for cats).

Perhaps

their most famous rescue is Shafa, who was found by drones trapped on the

exposed ledge of a completely bombed-out seventh-floor apartment, where she had

been perched for sixty days, with minimal food or water. Despite her advanced

age, they successfully nursed Shafa back to health. Since then, she has become

an online sensation, symbolizing Ukrainian resilience in her own grumpy cat

way.

Likewise,

Patron the Jack Russell terrier has also become an international influencer,

thanks to his work sniffing out landmines. Patron’s small size gives him an

advantage over other ordinance-detecting dogs, because he is too light to

set-off mines calibrated for human weight. That little guy is a charmer.

Unfortunately,

many of the stories Ptushkin documents are profoundly sad, like the two animal

shelters that took very different approaches when evacuating their human

staffs. Tragically, both shelters were near Hostomel Airport, which Putin’s

thugs and mercenaries bombed into rubble, greatly distressing the animals in

the process. Clearly, several on-camera experts suggest one shelter handled the

challenge in a much more humane manner, but the real villain is Putin, who put

both shelters directly in harm’s way.

This is a film built around real people, who, like reality TV stars, constantly

embarrass and disgrace themselves. In the case of these Russian soldiers, they repeatedly

confess to war crimes, wanton cruelty, jingoistic prejudice, and just generally

getting their butts kicked on the legitimate battlefield by Ukrainian soldiers.

They were calling home, but Ukrainian intelligence was listening. The resulting

recordings reveal the depravity and demoralization of the invading Russian

military in Oksana Karpovych’s documentary, Intercepted, which screens

during this year’s New Directors/New Films.

It

is easy to understand why Russian soldiers are not supposed to phone home. They

reveal a lot, but the intercepts the Ukrainian government chose to release to

the world expose the Russian militarist attitude rather than sensitive

intelligence. For instance, nearly every caller uses the terms “Khokhols” and “Banderites,”

which are Russian slurs for the Ukrainian people.

Several

calls frankly describe the intentional mass murder of Ukrainian civilians. They

are literally talking shooting people in the head and then dumping them in a

ditch. Much like the harrowing 20 Days in Mariupol, Intercepted should

be entered into evidence during a future war crimes tribunal.

The

confessions are truly damning, but the attitude of the Russians back home might

be even more disturbing. Their girlfriends, wives and mothers express outrage

that the Ukrainians are not welcoming the Russian invaders into their home,

even while literally cheering on the torture and killing of non-combatant

Ukrainians.

It is not often that political documentaries intersect with culinary docs. Unfortunately

for Ukraine, that is the case with this film. You can blame Putin because it is

entirely his fault. This Ukrainian restaurant is located in the East Village,

but its heart is definitely with Ukraine as it fights for its survival. Director-editor-producer

Michael Fiore shines a spotlight on the restaurant and the family that still

operates it, in Veselka: The Rainbow on the Corner at the Center of the

World, which opens this Friday in New York.

Originally,

Volodymyr Darmochwal founded Veselka (Ukrainian for “rainbow”) as a candy

store, when the Second Avenue area below 14th Street was considered “Little

Ukraine.” His son-in-law Tom Birchard was not Ukrainian, but he started working

at Veselka after college and somehow, he never left. Under his watch, it

evolved into a diner and then expanded into a landmark restaurant. His son

Jason (obviously half-Ukrainian) now runs Veselka and its related outreach

efforts, but his father is never that far from the house floor.

Fiore

provides a solid history of the restaurant, explaining how New York City’s

financial collapse almost ruined Veselka too. Nevertheless, it survived,

becoming a community institution that customers rallied around during freezing

cold era of outdoor pandemic dining. Yet, quite appropriately, Fiore devotes

the greatest screentime to Veselka’s role as a center of Ukrainian advocacy and

fundraising, following Putin’s brutal invasion.

In

fact, Veselka is surprisingly revealing in the way it documents the change

of attitude in the restaurant’s employees. At first, few of Veselka staff

beyond the Birchards are willing to sit for interviews, but as Putin’s atrocities

escalate, they feel compelled to tell their families’ stories on-camera. In

fact, there are a lot of poignant moments in Veselka, because the drama

is real and the potential for tragedy back home is a constant threat they must

live with. Fiore really brings that reality home, while avoiding any sense of

exploitation or manufactured melodrama.

The desire to erase Ukraine as a nation and the Ukrainians as a people did

not start with Putin. He just revived a longstanding Soviet tradition. In the

early 1930s, Stalin deliberately killed at least four million Ukrainians

through starvation and other contributing methods in what is now known as the

Holodomor. In this case, the “bug” of socialism’s poor performance became a “feature”

when applied to the brutal collectivization of Ukrainian agriculture. As both

writer and artist, Ukrainian Michael Cherkas depicts the true story of the Holodomor

through the fictional eyes of Mykola Kovalenko, the sole survivor of his

composite family, in the graphic novel, Red Harvest, which is now on-sale

where books and comics are sold.

Initially,

Kovalenko was born into a big, loving rural Ukrainian family. Their recent

harvests were bountiful, which should have been good news. However, Stalin’s

true-believing enforcers tar successful family farmers such as themselves “kulaks,”

or wealthy peasant. That might sound like a contradiction in terms, but it

really meant a class enemy, likely to be dispossessed and deported to work camps.

In

some ways, Red Harvest is the dark inverse of Fiddler on the Roof,

in which Kovalenko’s big sister Nadya marries Borys Shchurenko, an ardent

Communist activist, who whisks her away to the big city. However, unlike the

faithful Perchik, Shchurenko returns to sleepy Zelenyi Hai in triumph. Those

who are not blacklisted and deported are forced to relinquish their farms and

slowly starve, as all the collective crops are shipped to Moscow, to be

exported for hard currency. Instead of protecting the Kovalenkos, Shchurenko

betrays them, while brutally abusing Nadya.

Somehow,

Kovalenko, now a “Tato” (grandfather) himself, survived and escaped to Canada. He

is now the happy patriarch of another large family, who are safe from the

horrors of famine and collectivization. It is easy to understand why he rarely

talked about the Holodomor before the events of the current day prologue and

epilogue. Every time readers see the young Kovalenko loses another family

member, it is absolutely heartbreaking. Yet, this is still a survivor’s story.

Cherkas

opens a window into the devastating horror of the Holodomor by showing it from young

Kovalenko’s perspective. It is hard to fully grasp the enormity of it all, but

we can start by multiplying what happens in Zelenyi Hai, by hundreds of thousands.

It is not like these kids had it easy to begin with. In many cases, their

alcoholic parents had yet to inquire regarding their status, even after Ukrainian

social services revoked their parental rights. Then their welcoming halfway

home in Eastern Ukraine was forced to evacuate when Putin launched his illegal

invasion. When the troops crossed the border, filmmaker Simon Lereng Wilmont had

already finished shooting his Academy Award-nominated documentary A House

Made of Splinters, which airs Monday on PBS stations, as part of the

current season of POV.

Unlike

Eastern Front and 20 Days in Mariupol, House Made of Splinters

is not a war film, but the Russian dirty war in Donbass was indeed

stretching Ukraine’s already strained resources for social services. Frankly,

the three kids Wilmont focuses on are lucky to be there. Longtime educator/case

workers Margaryta Burlutska and Olga Tronova provided a sheltering environment

for the children, who were suddenly dealing with abandonment issues on top of

everything else.

The

Lysychansk Center was sort of a way station. Eventually, their residents either

leave for a state-run orphanage or foster parents recruited by Burlutska and Tronova.

Generally, fostering is the preferable option, but it essentially means the

foster children have given up hope for a further life with their dysfunctional

birth parents.

The

three focal children all must come to terms with that reality, which is

definitely some very real-life drama. It is also very depressing. However,

thanks to Burlutska and Tronova, some of the kids have relatively happy endings—at

least until the Russians invade.

They are a bit like Frederic Henry in A Farewell to Arms, but the war

is happening in their own country. For them, volunteering as a medics and

ambulance drivers was the only way they could serve during the war. Many started

in the Donbass region as early as 2014 and they continued to serve following

Putin’s full invasion, despite some being judged “unfit” for armed combat (due

to health reasons). Medic Yevhen Titarenko captures a country that is

remarkably unified, despite being under constant fire in Eastern Front,

his eye-witness documentary (completed with the editorial input of “co-director”

Vitaliy Mansky, the acclaimed documentarian exiled to Latvia), which premieres

today on OVID.tv.

You

will definitely see some things driving an ambulance around Kherson and

Kharkiv. That is why Titarenko started documenting the horrors he witnessed,

employing hand-held devices, smart phones, and body cams. Much of what he

captured is horrifying. Yet, some of the quiet moments are even more telling.

In

between their emergency calls, Titarenko and his fellow medics, relax, chew the

fat, and even celebrate being alive together. Many have similar stories, especially

those who hail from families with strong Russian connections. At first, they

were the odd ones out for supporting the Maidan protests. However, after Putin’s

illegal invasion, their parents and grandparents have become ardent Ukrainian

patriots. Their anecdotal evidence suggest Putin has ironically unified the supposedly

fractious Ukrainians—against Russia.

Eastern

Front is

a powerful and bracing film. However, it might unfairly suffer in comparison if

seen soon after Mstyslav Chernov’s jaw-droppingly harrowing 20 Days in Mariupol.

Yet, it has other merits, very definitely including the medics’ thoughts on

Ukrainian unity and Russian propaganda. Nevertheless, Titarenko’s concluding dash

through a war-zone can stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Normandy landing in Saving

Private Ryan.

One day, hopefully soon, this film will be entered into evidence in a war

crimes tribunal of Putin and his enablers. For ninety-plus minutes, it records the

systemic targeting of Ukrainian non-combatant civilians in the port city of

Mariupol. “War Crime” is simply the only term that suits the events Ukrainian

journalist Mstyslav Chernov and his Frontline and AP colleagues

documented, like snipers assassinating nurses entering a hospital, which have

no remotely credibly military justification. No matter what they might think of

Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, Chernov’s 20 Days in Mariupol will knock

the wind out of audiences when it opens this Friday in New York.

You

will see several children die while watching this film and you will share the

grief of their parents, even if you have no children of your own. Chernov (a

native of Kharkiv) and his colleagues were there to show the world what was

happening, but the Russian forces definitely did not want the story getting

out.

Right

from the start, they cut all power and internet access to the besieged city.

There were only a handful of hotspots where Chernov could file his reports.

Everything the world saw during the early days of the Mariupol siege came from

his efforts. That is why the Russians wanted him. It was not just about stopping

him. They also wanted to force him to recant.

Over

the course of 20 days, Chernov records a city in crisis. We see one hospital

shelled into rubble and another terrorized by sniper fire. Apartment buildings

with no reasonable military significance are regularly razed. Nobody is safe,

especially not children trying to enjoy a football game during an occasional moment

of calm.

You have to give the University of Toronto Press credit for their faith in

Ukraine. Even for “instant books” it takes weeks, more likely months, to

acquire, edit, design, sell-in, and print a new title. Ukraine now appears to

be winning back territory (so of course, Putin has responded with more war

crimes), but the prognosis for the invaded nation was probably not as

optimistic when this title started the publication process. However, it had an

urgent point to make, which is still valid. Former Ukrainian participants in a

Swedish program for migrant policy specialists (SAYP) react to the initial

horrors of Putin’s invasion in Gregg Bucken-Knapp & Joonas Sildre’s graphic

novel Messages from Ukraine, which is now on-sale at online booksellers.

When

Putin launched his full-scale war, Bucken-Knapp and his co-workers immediately reached

out to their Ukrainian colleagues, offering them shelter in Sweden, if they

could somehow reach the Scandinavian safe haven. Many of the initial responses

they received have been collected here, illustrated by Sildre (who also took an

active curatorial role). Some decided to stay and fight, while others decided

to flee—in a few cases carrying their pet cat or gerbil with them. For those under

siege in Mariupol, it was already too late to leave. Some expats considered

returning to fight, while others continuing applying their training to assist

their own migrant countrymen in Romania, or other surrounding countries.

Frankly,

the short Messages (30-some pages of art, plus supplementary text) probably

would have had more power if it had more fully developed two or three survivors’

narratives, rather than telling multiple sketches. People really need story and

character development to move them to action. There are some viscerally

expressive images in Messages, but its fragmentary nature limits its

power.

Presumably,

Bucken-Knapp & Sildre felt compelled to represent as a variety of voices,

which we can respect. The results still have great value and timely

significance documenting the shock and horror of Putin’s war—and the proceeds

go the Canada-Ukraine Foundation, so it is an altogether worthy endeavor.

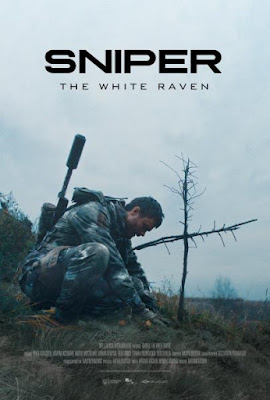

Ukrainian Mykola Voronin went on the same journey as Ron Kovic, but in the reverse

direction. He started out as a hippy, dovish ecology professor, before the

brutality of the invading Russians turned him into the Ukrainian Sniper. Sadly,

his pacificist principles did not deter Putin’s war criminals from their

scorched earth tactics. Channeling his rage, Voronin reinvents himself into a

warrior in Marian Bushan’s Sniper: The White Raven, which opens tomorrow

in New York.

Voronin

is a real-life figure and the events in this film are as real as it gets.

Before the invasion, he and his wife moved to the Donbas region to live in the

windmill-powered sustainable cottage he devised, where they also intended to

raise their unborn baby. Then the Russians came. Only Voronin survived.

Given

his bike-to-class lifestyle, Voronin was already reasonably fit, but he was

completely untrained in modern war-fighting. However, his desire for revenge

motivates him to learn quickly. Eventually, he volunteers for sniper training,

developing a talent for it, but he still needs to work on the required

patience.

After

all the flag-waving Russian propaganda movies set during WWII several genre

distributors embarrassingly proceeded to release during the early days Putin’s

full-scale invasion, it is nice to see the Ukrainian perspective finally get

some representation. (Make no mistake, Russians believe with a religious fervor

that their victory in Great Patriotic War gives them the right to control and

dictate life in Eastern Europe.) Yet, the psychological complexity of Pavlo

Aldoshyn’s portrayal of Voronin will still appeal to New Yorkers who are put

off by the faintest whiff of “jingoism,” (which only seems to apply to Western

democracies).

In

fact, everything about White Raven is scrupulously realistic, especially

the scenes of combat. They should look credible, because the large-scale

sequences often feature active-duty Ukrainian military personnel as extras.

Presumably, this is a story they could all relate to. Again, that makes sense,

since Bushan co-wrote the screenplay with Voronin himself.